The regional card game “guandan,” literally “throwing eggs,” has become one of the country’s most popular social activities

On an evening in April, 29-year-old Su Miao skipped dinner and drove 3 hours to an industrial park after work to join a card game. “Cards is more interesting than food to me,” Su, a public sector worker in Beijing who asked to be identified by a pseudonym for this piece, tells TWOC.

Su plays cards up to three times a week, often for hours on end. One weekend she spent six hours straight playing in the same room. Her obsession is partly due to a viral craze for a decades-old regional game: guandan (掼蛋, literally “throwing eggs”).

The game features four players in teams of two racing to empty their hands through card combinations before the other pair. Over time, it has accumulated an estimated 140 million fans, from the elderly in parks to young professionals in office lunchrooms. In Jiangsu province, the game’s birthplace, a folk saying goes: “Eating without playing guandan beforehand doesn’t count as a meal, and neither does eating without playing guandan after!”

In recent months, the game has become a nationwide craze. Guandan entered public attention after it was featured in state broadcaster CCTV’s Lunar New Year Gala in January 2023, before going viral later that year. Feng Jing, the manager of the card game website Bianfeng.com, told Qianjiang Evening News this February that daily active users of guandan on the platform increased by 50 percent in 2023, with a significant increase in users from outside of Jiangsu. New Weekly magazine labeled guandan “Game of the Year” in December.

This January, a school in Yichang, Hubei province, even offered their staff and students two decks of guandan cards as New Year gifts and announced they would include the game in their curriculum next semester. Su’s regular guandan spot is a room next to a golf driving range, whose owner jumped on the trend earlier this year by renting it out to card players. A guandan WeChat group established by the room’s owner now has over 100 members.

According to the Jiangsu Province Guandan Sports Association, four villagers from Huai’an, Jiangsu, invented guandan in the late 1960s or early ’70s by combining several Chinese card games. Its name comes from players’ “throwing down” (掼 in Huai’an dialect) tricks with four or more of the same card, known as “bombs (炸弹),” whose second character sounds the same as “egg (蛋)” in Mandarin Chinese.

Wang Jiulu, a 38-year-old from Xuzhou, Jiangsu, has played cards since his school days and learned about guandan from local retirees eight years ago. “Since around 2020 or 2021, almost all the restaurants in Xuzhou have had two tables in their private rooms, a round one for food and a square one for guandan,” Wang, who runs a company that sells guandan-related products, tells TWOC. His orders surged in the second half of 2023, with an uptick in sales to companies buying customized guandan sets as gifts for their clients.

Relationships (or 关系) are an integral part of doing business in China, and, for some sectors, guandan has replaced activities like mahjong and golf as the prime activity for building corporate connections. According to an article by China Business Herald last August, guandan is increasingly replacing Texas Hold’em as finance workers’ preferred bonding game with clients, driven by the growing presence of domestic investment.

Several entrepreneurs have raised the game’s profile in business circles. Zhou Hongyi, founder and CEO of the internet security company Qihoo 360, expressed his love for guandan several times on social media and in interviews this year. Meanwhile, this January, when Shanghai Guandan Sports Association was established with Qi Shi, billionaire chairman of stock information provider East Money, as its first president, a related hashtag received over 50 million views on the microblogging platform Weibo.

Zhu Di, a 35-year-old vice manager at a construction material company in Shenzhen, Guangdong province, believes guandan’s cooperative element suits client relations building. “Sometimes, you even need to sacrifice yourself to help your partner discard their cards first,” Zhu, who asked to use a pseudonym for this piece, tells TWOC.

When Zhu first heard about guandan two years ago, she considered it a kitsch game for the elderly. Last year, however, she started hearing more about it from clients, friends, and social media. She felt compelled to “catch up with the trend” in August. While previously, she would take part in heavy drinking sessions to network with clients, “Now, we usually play guandan after a business lunch or dinner,” she says. “We share thoughts on guandan skills and work during the process…[Guandan] is a great tool for maintaining existing connections and making new ones.” Zhu claims her regular guandan teammate won several clients and business worth up to half a million yuan by playing the game with the right people in his office.

Guandan’s simplicity has also driven its popularity. Unlike other poker varieties that require chips and can seem complicated to beginners, and golf, which is expensive and time-consuming, guandan can be learned in 10 minutes and requires only four people, two decks of cards, and a flat surface. It is also more sophisticated than “fight the landlord (斗地主),” traditionally one of China’s most popular card games. “Guandan is much more flexible…Everyone can have their own strategy for deploying the 27 ‘soldiers’ in their hand,” says Wang, the guandan business owner, comparing playing the cards to preparing an army for battle.

“It’s a wrestling of mind and psychology,” says Su, the Beijing public sector worker. She enjoys “making [opponents] unable to guess my cards and strategies...It also feels great if we cooperate well, no matter whether we win or lose.”

For a decade, officials have also promoted guandan. The Huai’an local government listed guandan as an “intangible heritage cultural item” in 2014. In September 2022, the General Administration of Sport of China released guideline rules for guandan competitions, and in October 2023, the game debuted at the 5th National Mind Sports Games as a demonstration event, alongside regular games such as Chinese chess, bridge, and five in a row. Wang’s company has organized community guandan competitions as part of local government public service campaigns that feature lectures from officials or police officers on, for example, avoiding scams.

But not every event is so upright. This January, an op-ed by the Beijing News warned about guandan enabling corruption or inappropriate “favor trading” between businesses and officials. It cited a case in Jiangsu in 2020, where 18 officials gathered to eat, drink, and play guandan in contravention of local pandemic prevention measures, and another from Anhui province in 2022 when seven cadres left their Party training without requesting leave to accept a dinner and guandan invitation.

Similarly, in a Weibo poll on the Yichang elementary school including guandan in its curriculum, over 30 percent of the 905 respondents opposed the practice, with some suggesting the game could be a gateway to gambling. “Isn’t there anything else to teach them? Or are you just educating them to become Las Vegas fans?” one Weibo user commented.

In reality, gambling through guandan seems rare (unlike with many other Chinese card games). Su, Zhu, and Wang all say that they have never encountered guandan being played for money. One reason could be that it is too easy to cheat by communicating with one’s partner or even looking at their hand and telling them what to play next (both formally forbidden in the rules).

But even without gambling, Wang still sees money to be made in guandan as karaoke, drinking sessions, and golf decline in popularity among young professionals. He thinks guandan’s popularity will persist for at least a few more years. Even if the trend dies down, “all the connections we’ve established through guandan can be our future sales channels,” he says.

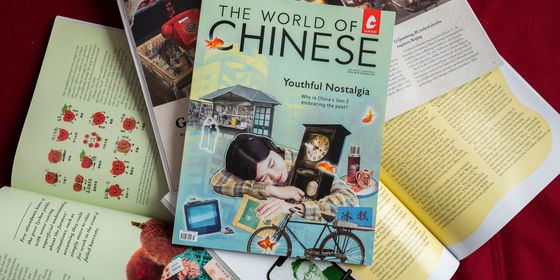

Throwing Eggs: How “Guandan” Became China’s Favorite Card Game is a story from our issue, “Viral Attractions.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.