Women in China’s lower-tier cities and towns are increasingly buying gold accessories for investment and prestige

Wang Yuan is a young woman from Xiaogan, a prefecture-level city in Hubei province, with a habit: buying gold.

Ever since she passed the exams to become a civil servant, with each bonus Wang collects from work she rewards herself with gold jewelry. In fact, she spent nearly 3,000 yuan on a birthday present to herself this year: a gold pendant in the shape of a lily of the valley flower.

Wang resigned from an ailing travel company in Shenzhen, Guangdong province, in late 2020. When she was studying for the civil servant exam, her social life was sparse, so buying clothing and accessories was her sole antidote for stress. Wang reined in her urges during her unemployed spell, only allowing herself to buy cheap hair trinkets from online retailer Pinduoduo. Her shopping spree only gained momentum once she’d finally landed a stable government job.

Nowadays, Wang swears by a simple motto: “It’s all about enjoying life.”

Recent newlywed Chen Qianlu is also partial to gold. Last year, she took to social media to show off a jewelry ensemble commonly known as the “gold trio set (三金)”—a collection of three pieces of jewelry traditionally offered by the husband’s family to the bride at Chinese weddings.

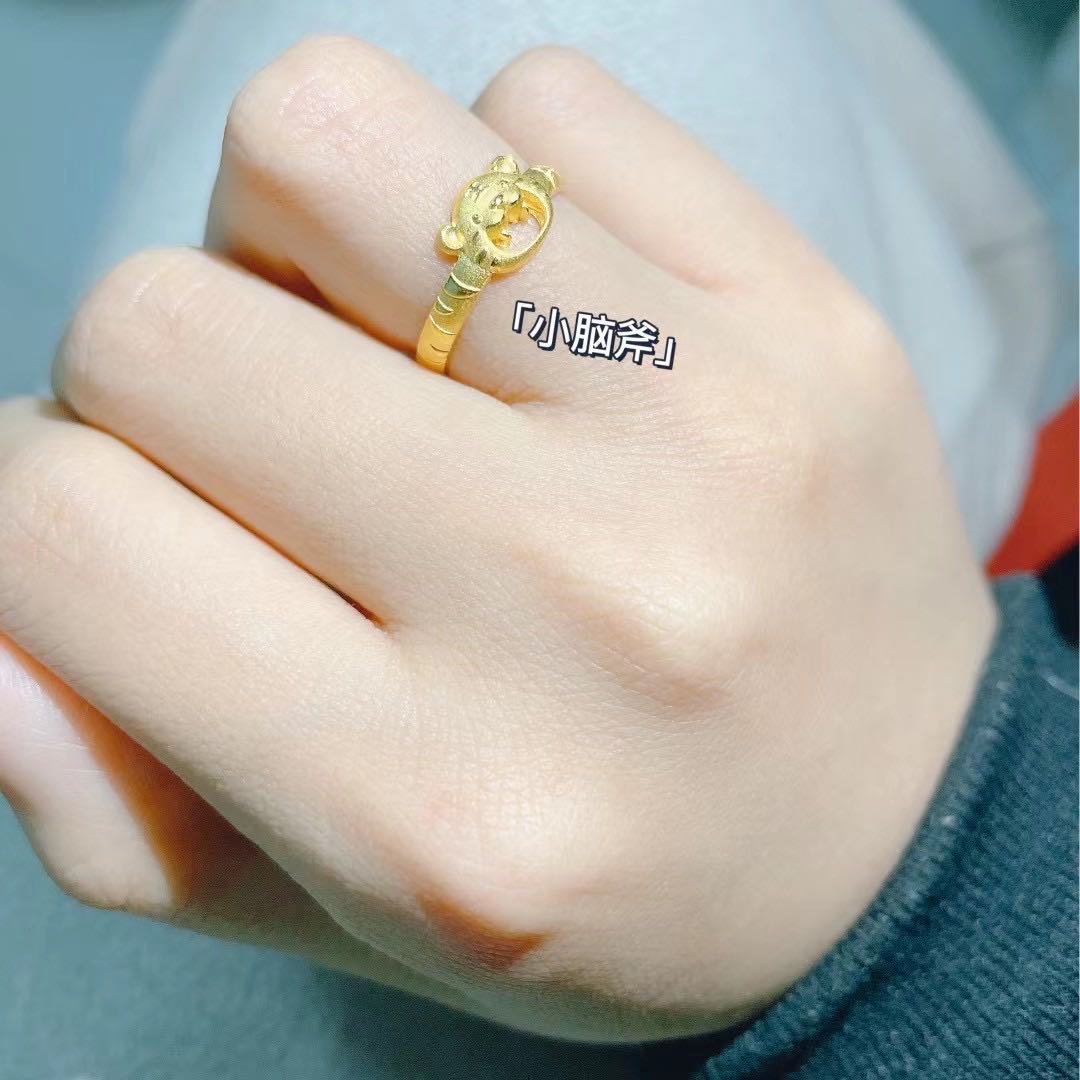

The set can extend to a total of five pieces—a necklace, a ring, a pair of earrings, bracelets, anklets, and pendants. Among Chen’s set was a ring in the shape of a grinning tiger. “My husband promised me that he’d add to the collection every year,” Chen posted on her WeChat feed.

On Valentine’s Day this year, Chen posted a picture of a brand new gold ring, mounted with a little rabbit. Her triumphant caption read, “Well, I’ve got the tiger and the rabbit in the bag! Two down, another 10 to go,” a reference to the 12 animals of the Chinese zodiac.

Born in 1998, Chen’s first employer was a state-owned enterprise in Guangdong province. The Covid-19 pandemic and the death of her grandfather inspired her to seek stability and peace closer to family. Chen eventually moved to Xiaogan, her now-husband’s hometown, to work at a local administrative office managing neighborhood affairs.

Wu Meng, a married high-school teacher in her hometown of Heze county, Shandong province, has also become enamored with gold jewelry in recent years, spending up to one-third of her living expenses on these products during her most enthusiastic shopping sprees. She is now trying to control her spending, seeing as the money comes from the family funds. “My husband wouldn’t be happy to see me blowing our hard-earned money,” she says.

Like many other young women in lower-tier cities, Wang, Chen, and Wu regard gold jewelry as a marker of modest prosperity and stability.

The slump experienced by the gold jewelry market in 2022 as a result of Covid-19 is over—there are signs of a gradual rebound in gold prices, both in China and internationally. Nevertheless, Chinese gold brands are now competing for dominance in the so-called “sinking market (下沉市场),” a term referring to China’s small-town and rural markets.

Hong Kong-based jewelry conglomerate Chow Tai Fook’s 2023 annual report, showed it opened 709 new retail points in lower-tier cities, more than in first- or second-tier cities. Another Hong Kong-funded enterprise, Luk Fook Holdings, stated in their 2023 financial report that they plan to open 300 new stores this year, mainly in fourth- and fifth-tier cities.

These brands are all targeting young women in small towns like Wang, Chen, and Wu.

Finding financial security in gold

Wang’s love for accessories can be traced back to her college days. Born in 1996, she worked at a bank for a while after graduation before switching to the finance department at a tourism company in Shenzhen, a city known for its high living cost. Wang earned a good and steadily increasing salary, but it came at the cost of long subway commutes and diminishing leisure due to frequent overtime. She had no energy to dress up. “My wardrobe was actually very limited back then. Wearing a skirt was a rare event,” says Wang.

Then came Covid-19. The travel company that employed Wang lost all of its overseas business, with domestic revenue crashing as well. Back in her native Hubei, the epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak, Wang’s parents were not in good health either. However, going home for visits was not so easy: “People frowned at the mere mention of Hubei.”

Before large-scale layoffs happened at her company, Wang resigned at the end of 2020 and returned to her hometown Xiaogan, where she sat the civil servant examinations and got a job at the local administration office in 2021.

Upon settling down in her new small-town life, Wang’s love of jewelry rekindled. Her work now is procedural and the tasks are straightforward. Even though the monthly salary is modest, a little over 3,000 yuan after taxes, life in small towns is rather cheap, even more so for civil servants living in dorms provided by their company or public rental housing.

As far as their price tag goes, Wang’s accessories have a wide range. Her gold pieces, mostly small items she can wear to work, cost anywhere between 1,000 and 3,000 yuan. The rest of her collection is made up of cheap stuff—at most over a dozen yuan—from Pinduoduo or the online wholesale platform 1688.com. “You know, there’s no need to be shy about the reality of money. Limiting your splurging only means you can buy cheaper, equally beautiful stuff in greater quantities,” Wang says.

With this approach in mind, Wang takes pleasure in admiring her more affordable purchases. They tend to be vintage styles that she uses for retro photo shoots with friends. She invites her female friends to her place to get dolled up—make-up, hair, and wear a qipao. Then, they’ll take over the streets for a perfect vintage Chinese photoshoot. Wang’s WeChat posts often feature travel pictures of her wearing those accessories, with her friends often complimenting her in the comments below. “I like sharing my beautiful collection with them in this way,” she says.

But Wang also gains a sense of financial security in the stability of gold. Even though gold bars and beans retain their value better than gold jewelry, as the latter comes at a premium due to design and processing costs, Wang still enjoys buying them. “It’s still gold. And as a strategic reserve asset, gold remains relatively stable so I can reassure myself that buying more is okay,” she says.

Wang is far from being an isolated case among her peers. In recent years, the number of younger jewelry buyers has increased. The World Gold Council, an international industry association, issued its Market Trend Insight Report in 2022, stating that more than 80 percent of consumers buying gold jewelry for weddings or as gifts are young people aged 25 to 35.

Nowadays, brands are launching more styles of gold accessories that cater to their younger customers. Wang laments that the price is now the only limiting factor that stops her from buying more: “Designs are always really beautiful, but I can’t always afford them.”

Chen recalls that gold jewelry, specifically chunky rings, used to be code for old-fashioned, tacky privilege exclusive to a certain type of social class. However, when she got married, she discovered a range of new delicate designs for young customers. She starts to truly appreciate their beauty once she tries the jewelry on—the necklace and the cute little tiger-shaped ring complement her slender neck and fingers.

Gold jewelry brands are also vying for their youngest clientele through online channels. The industry used to rely on offline retail as its main access point, where it netted over 90 percent of its sales. But e-commerce sales have continued to grow in recent years—from a mere 5.4 percent of the industry in 2017 to 9.9 percent in 2021, according to data from Guosen Securities.

As things stand, Xiaohongshu, China’s Instagram-like social media platform, is a key battleground these brands fight over. According to business news outlet Consumption Frontier, there are over 1.74 million mentions of Chow Tai Fook on the platform. Jewelry on Wang’s wishlist is all from posts she saw on Xiaohongshu—from vintage Chinese round earrings carved with flowers to rose necklaces, lucky golden bead necklaces, and more. On Xiaohongshu, Wu even posted an unboxing video of the haul she’d scored from a livestream on Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok.

Gold beans have also gained popularity thanks to promotions on Xiaohongshu. Produced in a standardized fashion, these beans are sold by the gram and bought mainly as investments. Xiaohongshu user Qiyaris highlighted the latter aspect in her video “Girl Finances 101: How to Quietly Become Rich”: “When you spend money on gold, it’s not so much an unnecessary expense but an investment. The former you should rethink; the latter builds wealth. Sure, you want some milk tea, but ask yourself—how much gold could you buy for that money? Go without and that’s 0.1 grams of gold you can now afford.”

Bohu Finance, a business media outlet, tracked the growth of the gold beans industry with data from e-commerce giant Taobao: Back in 2021, only three businesses from Shenzhen’s Shuibei, the most influential and largest jewelry-specialized trading market in China, sold gold beans online. Just one year later in 2022, almost all of them had their own versions of the product.

Gold and weddings: A perfect match in lower-tier cities

Marriage is usually the starting point for many small-town women’s fascination with gold jewelry.

Such was the case for Chen. She grew up in a county under the jurisdiction of Huanggang city, Hubei province, a place where custom mandates that the groom-to-be presents his future bride’s family with the “gold trio set” on the occasion of his first formal visit. A wedding date will be arranged on the second visit, followed by the engagement banquet and the wedding.

Chen’s then-boyfriend fulfilled the tradition during his first visit in a jovial atmosphere marked by the presence of the bride’s entire set of uncles and aunts. He handed his future mother-in-law a beautiful bag containing the gold trio set, as well as a betrothal gift box with 100,000 yuan and an assortment of tobacco, wine, and meat.

Chen’s mother knew better than to open the jewelry bag on the spot. Instead, she waited for the right social cue, brought by smiling relatives and friends asking to take a look at the pieces and heaping praise accordingly.

According to a survey by the World Gold Council, the wedding-related demand for gold jewelry amounted to 28.1 percent of the total market in 2020. With the demographic of this precious metal skewing increasingly younger, though, the demand for everyday gold jewelry is gradually exceeding that of weddings.

In lower-tier cities and counties, gold is a girl’s best friend—or at least it wins over diamonds in terms of its market penetration rate. Data from the World Jewellery Association shows diamonds’ penetration rate (that is, the percentage of all jewelry buyers that purchase diamonds) at 61 percent for first-tier cities in 2021, with the figure dropping to 48 percent for second-tier cities and as low as 37 percent for third- and fourth-tier cities.

Diamonds still equate to high-end romance, and young lower-tier city and town dwellers are much too pragmatic for any of that. Wedding rings mounted with natural diamonds weighing merely between 0.3 to 0.5 carat—around the size of a mung bean—often sell for over 20,000 yuan. Meanwhile, you only need a couple of thousand yuan to buy a wedding ring with two, maybe even three grams of solid gold.

“Diamond rings have a rather high premium, but I don’t think they hold value all that well. The actual cost might not be that high, but once it’s branded, they sell it for tens of thousands,” Chen says. When Chen got married, she didn’t look at any diamond brands for a ring but relied on friends to find her way to buy from diamond factories directly. Eventually, 4,000 yuan bought her a ring with a diamond weighing a decent 0.3 carat.

After Chen got married, wearing gold evolved from being only a custom for weddings to part of her daily routine. She wears a gold ring every day. During a recent dinner date with her husband at the mall, they hit the counters of Chow Tai Fook purely on a whim. Chen’s perennially busy husband’s gifts of gold jewelry amount to a love language of sorts. They’re also a sign of his material contribution to their marriage as he may not concern himself with many other household matters.

Wu, the high school teacher, also got her own “gold trio set” on the occasion of her wedding and found that gold suited her the most after trying out other materials like jade, jadeite, and agate. A student’s red bracelet, strung with small gold beads, first caught her attention before Douyin lured her in with tempting livestreams hosted by gold stores. Soon enough, Wu was buying herself gold beads, then pendants, and finally entire chains.

Wu prefers to stay discreet with small yet exquisite pieces: thin chains and equally inconspicuous pendants. They spruce up her daily outfits and are consistent with her image as a teacher. “I avoid flashy pieces that are too thick or excessively large,” she says.

Wearing expensive jewelry in small towns can be a sensitive matter. Wu still purchases the pieces she likes but acknowledges the social taboo. “To be honest, when I do splurge on whatever piece I’d been looking forward to, the fear of what others may say keeps me from wearing them sometimes,” she says. And people do talk; once, a colleague taunted her on account of a new piece: “Oh, you’re always buying those. You’re so well off, aren’t you?“ Wu just smiled in response. “There are always people who are quick to judge, right? But, I admit that those words would pop into my head when I wear gold sometimes,” Wu says.

This is also part of the reason why Wang has ditched the crystal rhinestones she used to buy from brands like Swarovski, aside from their lesser value and higher premium. “People in my neck of the woods won’t know that those earrings you’re wearing cost you some 3,000 yuan until you tell them. Then, they will absolutely think, and say, that they’re not worth the price tag. That’s how it is here.”

A reward for stability

For many women in small cities and towns, gold represents stability and prosperity. After Wang quit her job in Shenzhen and returned to her hometown in Xiaogan, she took a public sector position. Though she gave up on the career ambitions she harbored in the travel company, she doesn’t regret leaving the stress of big city life behind.

Now she tries to enjoy every moment. “I’m not going to skimp on my expenses. Whatever I enjoy, I will not go without just to save money,” she says, explaining her spending on jewelry in particular. She used to spend her spare time dreaming of promotions, salary raises, and ever-higher bonuses when she worked for private enterprises. Now, she could not care less.

Her current wages are based on a fixed plan that sets a path for yearly increases. Wang’s ambitions now are limited to a meager end-of-year bonus that won’t go beyond a few thousand yuan, or else a mention as an outstanding worker. However, she doesn’t pursue those, either. “I don’t want to work overtime anymore. I just want to lie down and relax.”

When a bonus does reach her bank account, Wang will spend it on the next item in her gold jewelry wishlist. “If I can’t spend my salary on my hobbies, what’s the point of having a job anyway?”

Written by Wang Qin (王沁)

Edited in Chinese by Fang Yuan (方远)

This article originally appeared in Chinese in Zairenjian Living. It has been translated, edited, and reprinted with permission.