Content in dialects is booming on social media, but is that enough to save them from extinction?

Qian Shengdong has over 1.5 million Weibo followers, but perhaps less than 30 percent of them can fully understand everything he says in his videos.

That’s because the 34-year-old vlogger’s content, which features him personifying different districts of his native Shanghai or dressing up as a stereotypical local auntie, is not always in Mandarin Chinese (Putonghua), but often mixed with his local dialect: Shanghaihua.

To his fans, Qian, better known as G Sengdong, the transliteration of the dialect pronunciation of his name, is an ambassador of Shanghaihua and contemporary local culture. But off-camera, he rarely speaks the dialect with the team of interns who work on his videos, mostly Shanghai locals born around the year 2000. “It would be weird if I spoke Shanghaihua and they replied in Putonghua,” Qian tells TWOC over the phone. “Half of them don’t speak the dialect at all.”

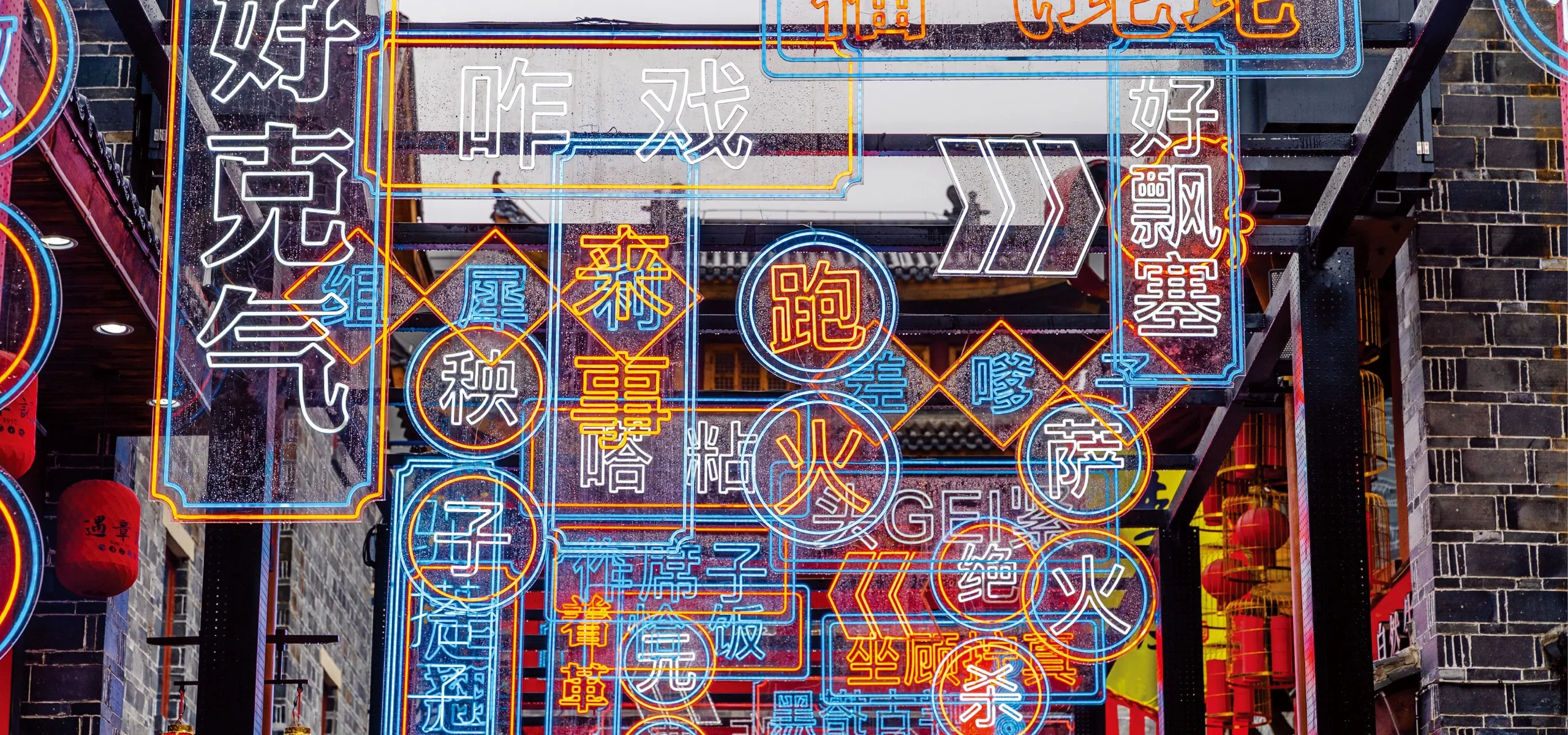

Qian’s videos are part of a growing trend online of Chinese content in dialect, or fangyan (方言), spurred by social media platforms that have made it easier than ever for fangyan speakers to connect with local audiences and even appeal to those who don’t speak the dialect.

But while fangyan videos may be becoming more popular, and the government is belatedly seeking to preserve dialects as essential parts of local culture, decades of Putonghua promotion in schools and official contexts has seen the use of many of China’s hundreds of local dialects decline significantly. Putonghua, the official national language now spoken by 80 percent of the population, is still perceived as a gateway to better employment prospects, social and geographic mobility, and national unity.

In recent years, viral videos on social media have popularized non-Putonghua phrases like the word yue in the Henan dialect, which means “to vomit” and was rediscovered in 2020 supposedly because of the 2012 film Just For Fun. Meanwhile, qiafan, a phrase that means “eat food” in many dialects including Xiang and Gan (dialect families mostly found in Hunan and Jiangxi, respectively), became popular online around 2019, with its meaning extending to a way to mock people who do things they are not proud of for a living.

In May this year, a video of a 29-year-old migrant worker named Cai Jinfa proudly shaking his blond mullet and lip-syncing to “I Am From Yunnan,” a 2020 song featuring vocabulary in the Lisu language and repetitive beats, inspired people from all over China to follow suit, adapting the song to their own dialects (one version even features animated Terracotta Warriors singing in the local dialect of Chang’an district in Xi’an, Shaanxi province). In just a few days, the original video received more than a million “likes” on short video platform Kuaishou, while spin-off posts featuring the hashtag “I am from Yunnan” on Douyin, China’s TikTok, accumulated more than one billion views.

Yet overall use and fluency of fangyan across China has been in decline for decades, with Putonghua increasingly taking their place, at least in the public sphere. According to a 2004 survey led by the State Language Commission under China’s Ministry of Education, 86.4 percent of Chinese can use fangyan to communicate, while around 80 percent now speak Putonghua, up from around 50 percent of the population in 2000. In 2017, China Youth Daily found that of 2,002 mostly urban residents they surveyed, only 62.8 percent could speak their hometown dialect.

Despite Qian’s success at vlogging, which earns him enough income to be his full-time job, he is pessimistic about the prospects for Shanghaihua to survive among the next generation. Whenever Qian nudges his interns to speak more, “They say, ‘it’s too embarrassing,’” he notes. “Two or three years ago I was worried about the future of Shanghaihua, but not anymore,” Qian says, before pausing for the punchline: “Now I’m sure it is going to die out.”

The decline in use of dialects can be traced to the promotion of a common national language, something that has occupied the minds of Chinese scholars since the late 19th century. The Putonghua which is defined as the “national common language” in Chinese law and enshrined in the Constitution today first emerged in 1955. In October that year, 207 representatives from all of the 28 provinces of China at the time voted on 15 shortlisted dialects, selecting the Mandarin Chinese variant regularly used around Beijing as the basis of what would be known as Putonghua (literally, “common speech”).

Novelist Lao She (老舍) supported the need for a common language at the meeting, recalling his own experience in secondary school in Beijing, where classmates’ different dialects and accents brewed prejudice and misunderstanding, dividing a class into cliques: “Analogously, whether language is in unity or divergence is an important matter relating a nation’s integrity, as well as its rise or fall.”

But the Mandarin category, which contained the Beijing variant that formed the basis of the common language, is just one of the eight to ten official categories of Chinese dialects. The others include Jin, Min (which includes Hokkien), Hakka, Cantonese, Xiang, Gan, and Wu, each containing sometimes dozens of sub-dialects that are not necessarily mutually intelligible. For example, some Wu dialects, such as Wenzhouhua and Qian’s Shanghaihua, are mutually unintelligible. Most of the Mandarin sub-dialects, on the other hand, are closely related to Putonghua.

From the fall of 1956, the State Council required all elementary and secondary schools, excluding those serving children of non-Han ethnic groups, to carry out language and literature courses in Putonghua.

By 1972, when Ding Dimeng, a retired associate professor of Chinese Language at Shanghai University, was in middle school in Shanghai, teachers of all subjects were required to teach in Putonghua. “My math teacher used to give fantastic lectures, but after he was required to use Putonghua, he didn’t even know how to talk…we were all asking him to switch back to Shanghaihua,” Ding recalls. In 1992, the Shanghai government took programs in the local dialect off its TV stations, and told students not to use Shanghaihua in school.

Ding believes fangyan and Putonghua should be allowed to develop in parallel, and should not be viewed as in conflict with one another. In fact, Ding’s career started with teaching Chinese as a second language and popularizing Putonghua. But in 2001, while surveying local schools on their Putonghua levels, she noticed that “if a student speaks so much as one line of Shanghaihua on campus, they would no longer be eligible for honors, and their class can no longer get class honors,” she says. Even the bathroom wasn’t a safe space—if a student was reported for speaking fangyan, they would be called in for a telling-off in the teacher’s office.

In 2014, the National Radio and Television Administration required all TV and radio hosts in China to only use Putonghua except where there is special need, further sidelining local mother tongues into the private sphere.

Since then, the burgeoning social media scene has provided the bulk of new opportunities to broaden fangyan appeal. When Qian first sat down in front of a camera in 2015, jumping on the vlogging bandwagon, it was only natural that some of his lines came out in Shanghaihua, his “everyday language,” as he tells TWOC. He didn’t intend to base his content on local life, but “it’s just that when I spoke Shanghaihua, people liked it. They asked me to do that more, so I did.” Yet as his fame grew, Qian started to feel a “sense of responsibility” to use his platform for dialect protection.

Demand for dialect content does not only come from locals seeking a connection with their native area. Yang Zhilin, a 31-year-old Sichuan native who has been living in Shanghai since 2013, follows Qian’s account to learn more about the city he now lives in. “I like the culture and daily life in Shanghai, so I would also like to better fit into this place and people,” he explains to TWOC.

For Yang, who originally hails from Chengdu, Shanghaihua also serves a practical purpose, and he often spends his free time taking lessons in the dialect from a private tutor. He’s now at an advanced level: being able to successfully argue with the locals. After he dissuaded a middle-aged man from cutting in line in front of him a few months ago, Yang heard the man complaining to his wife in Shanghaihua about the “non-native.” To their astonishment, Yang fired back “Non kaon sa (What are you talking about)?”—it’s an experience he’s still proud of in his Shanghaihua journey.

Using dialects online can help navigate other tricky situations. There are examples online of vloggers using dialect to evade censorship by internet platforms, often captioning their video with more vanilla Putonghua while saying something different, and more controversial, in dialect.

Some platforms have, in the past, removed content livestreamed in fangyan. On Douyin, only “Putonghua is allowed as the language of daily exchanges,” except for cases like “singing English songs” and “teaching foreign languages,” an employee explained in a video on the company’s official account in 2020. The same year, media platform gznf.net reported multiple examples of fangyan livestreamers receiving warnings or being temporarily banned from Douyin, with multiple screenshots showing messages from the platform reading “please try to use Putonghua.”

Perhaps the platform thinks that “if you speak fangyan, I cannot monitor you anymore,” Qian speculates. At the moment, such regulations don’t appear to have affected non-livestreamed content.

As Qian’s career suggests, fangyan content can still be successful online, and provide a creative outlet for expression. When Xu Zeming, a musician from Kunming, Yunnan province, mixes Kunminghua into his rap songs, he feels he’s getting closer to the true spirit of the genre. “There is this unique aspect of hip hop culture, which is that we should represent the place where we come from…so we carry that sense of pride,” Xu tells TWOC, adding that the flatter tones of the local dialect make it sound “cooler” to rap in than Putonghua.

“Music is a way to document language and its art,” Xu says, “I hope in every period in time, Kunming can at least retain a uniquely local way of expression.” That uniqueness, to Xu, also includes the area’s ethnic diversity. In his song “Tequila Sunset,” for example, Xu weaves together Cantonese verses and Haicai Tunes, a traditional musical form in the Yi language, into a time and space-bending flow.

Xu’s merging of fangyan and different ethnic languages, including Putonghua, might point to the future of dialects across the country. The State Language Commission, for example, has run a national language and dialect protection project since 2015 which has so far surveyed and collected 10 million sample recordings for more than 120 Chinese dialects and ethnic minority languages, many now accessible on an open database, including multiple entries from Shanghai and Kunming.

Regional governments, too, have begun to promote fangyan as part of local culture. In 2017, Wuhua district in Kunming started incorporating fangyan into kindergarten education through teaching folk rhymes and games. For the past two years, Shanghai’s municipal language commission has required all kindergartens to send one or two teachers to attend training to learn how to speak Shanghaihua as well as how to teach it. Similarly, Guangzhou has already held six editions of an annual “Lingnan Nursery Rhymes Festival,” with children in glitzy costumes reciting nursery rhymes or ancient poems in Putonghua, Cantonese, or Hakka.

Various districts in Shanghai have also been organizing children’s Shanghaihua competitions in which Ding often sat as a judge, though she complains that “[the kids] run to me as soon as they go off the stage and ask, ‘Teacher, how did we do?’ in Putonghua.”

Still, Ding believes the emergence of more fangyan content online shows is a positive trend. “There is still a soil for fangyan [to grow]...without too much intervention, it can naturally grow back,” she says.

One downside of online fangyan content is the limited audience, which may discourage full-time vloggers who depend on internet traffic to make a living. A 2021 survey on fangyan vloggers on Douyin found that they rarely top the “trending” lists in their region, and there is a dearth of vloggers in most dialects other than Mandarin and Hakka. The majority of fangyan content creators are middle-aged, with young people in the minority.

Qian thinks the conversation regarding fangyan needs to move on from discussions of heritage and tradition—it cannot survive on nostalgia alone. “[Shanghaihua] doesn’t feel lively,” he muses. “Why can’t we talk about young people? Why can’t we talk about how they go clubbing, fall in love, hang out in malls, or play [the popular mobile game] Honor of Kings in Shanghaihua?”

Changing attitudes is a difficult proposition, however, as not everyone is so concerned about the declining use of fangyan. To Liu Mianzhi, a woman in her late forties in Nanchang, Jiangxi province, Nanchanghua (part of the Gan dialect family) is the language dedicated to speaking with grandparents and bargaining in the market. Liu decided not to teach Nanchanghua to her son, now 14 years old, after having worked in a kindergarten where she claims the children who spoke the dialect tended to have stronger accents and more difficulty learning Putonghua.

Though linguistic studies around the world suggest that children who grow up in bilingual environments are not more likely to experience language difficulties, Liu’s views are not uncommon in China—or even in Nanchang, where according to a 2017 poll by Nanchang Evening News, 70 percent of parents in the city didn’t speak the dialect to their children. “I want my child to be able to go to bigger cities…and not to limit himself to a small place like Nanchang,” explains Liu.

She hasn’t heard of any places where one can formally learn the dialect in Nanchang, a city with around 20 percent of Shanghai’s population and 10 percent of its GDP, and knows of just one show on TV with some Nanchanghua content. “You can only learn it from your family, or go to the older districts and listen to the elders speak it in the street,” she says.

Even when dialect content is spread online and in media, it is not always flattering to its speakers. Henanhua, which is categorized as Central Plains Mandarin and more mutually intelligible with Putonghua, compared to Shanghaihua or Nanchanghua, has become synonymous with negative stereotypes of people from this agricultural province: dishonesty, organized crime, and scams. Du Qingjie, a 28-year-old filmmaker from Xinxiang, Henan, recalls the thieves who steal livestock in the 2009 comedy film Cow, a fictional story set in Shandong province: “They really didn’t have to make the bad guys speak the Henan dialect.”

Almost a decade later, Zhang Huashan, a lawyer from Henan based in Xi’an, tried to sue Beijing TV for a comedy skit in the station’s 2017 Lunar New Year Gala, in which a scam caller character spoke Henanhua, while the “good guys” both spoke Putonghua. This year, a skit on CCTV’s national Spring Festival Gala had Jiang Kun, a famous comedy actor from Beijing, comically explaining how to speak Cantonese, to the embarrassment of many native speakers online. “[While such content] might not be outright discriminatory,” Du believes, “it can perpetuate stereotypes.”

Other dialects appear to be in better health. Yang, the Chengdu native in Shanghai, describes Chengduhua as “like legends and folklore...it’s a childhood memory shared by a people.” He also feels the dialect is “still going strong. There’s no need for special protection.”

Sichuanhua, of which Chengduhua is a variety, is the main dialect in Sichuan and Chongqing, a region that has a combined population of 112 million. Yang notes that multiple screenwriters in recent years have incorporated the often sarcastic, or “sharp-toothed” as Sichuan locals might say, the Sichuan dialect into movies and TV shows, while most children are still willing to speak it. In recent years, there is also a robust genre of rap in Sichuanhua produced by musicians who hail from the region.

But while dialects are thriving in some places, drives to get more of the population speaking Putonghua also continue apace. This January, the Ministry of Education and the National Rural Revitalization Administration announced that they are pushing ahead with plans to get 85 percent of China’s population speaking Putonghua by 2025, up from the 80.7 percent this year.

Ding believes it would be a “crime against history” if dialects were to fall out of use completely. “We might as well throw away all regional operas then, because they won’t work without dialects,” she says. To preserve fangyan, she suggests that the government puts out an official policy to develop dialects in parallel with Putonghua, for schools to stop punishing children for speaking dialects outside of class, and for TV stations to create bilingual versions of shows, especially shows for children.

At the grassroots level, she has given talks encouraging parents to stop deliberately or only speaking Putonghua to their children if they themselves communicate in fangyan, as children learn Putonghua in schools anyway. “What I’m really urging them is to preserve their cultural roots, because language is the root of culture,” she says.

The push-and-pull between Putonghua and fangyan continues to be a balancing act of culture, communication, and identity. “Between synthesis and heritage, you win some, you lose some,” Liu, the parent from Nanchang, believes.

Qian still intends to keep producing content in Shanghaihua, even if it might limit his audience. “[If] you’re already in intensive care, you still need to try your best…I should still take out a defibrillator, right?” he says, analogizing his attempt to keep the dialect alive.

He points out that a time-traveler from 1930s Shanghai might have difficulty recognizing the dialect today. “I think fangyan develops dynamically. Maybe 80 years from now, Shanghaihua might [still] exist, in a different form…that’s how I console myself.”

Speaking Up: Can Social Media Save China’s Dialects? is a story from our issue, “Public Affairs.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.