A new science fiction and fantasy anthology shows the best of China’s growing canon of female and non-binary authors

Only a tiny percentage of China’s fiction trickles its way into English every year. According to lists compiled by Paper Republic, of the 17 works of contemporary novel-length fiction translated from Chinese in 2021, 11 of them were written by male authors aged 50 and above, like Liu Cixin and Yan Lianke.

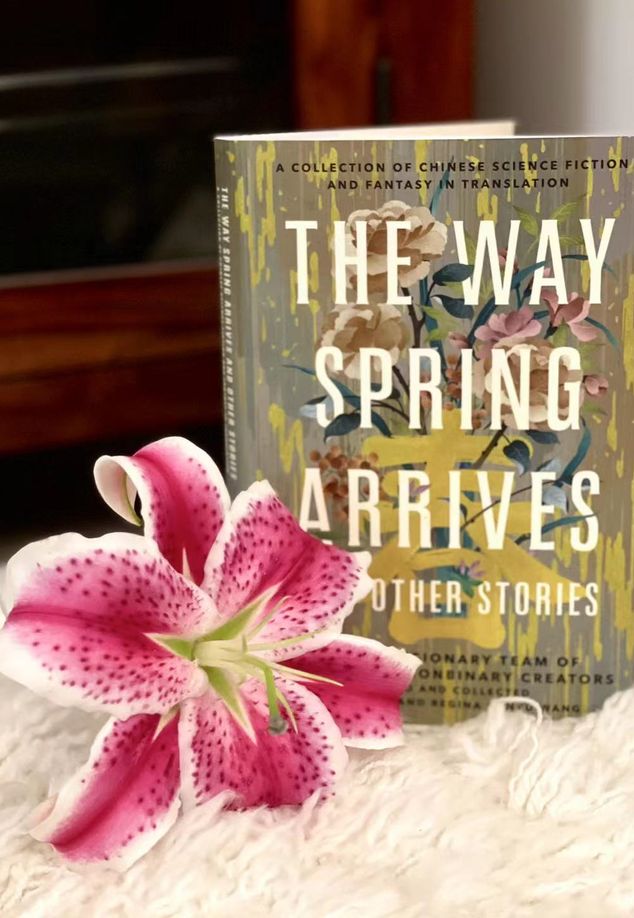

The Way Spring Arrives and Other Stories, an anthology of sci-fi and fantasy short stories, is hoping to change this picture. Published simultaneously by the Shanghai Literature and Art Publishing House in Chinese, and in English by sci-fi and fantasy imprint Tor.com earlier this year, the book was written, translated, edited, and designed by a Chinese female and non-binary team. Many of the 17 stories included originated as “net novels,” literature circulating mostly through online literature platforms like Qidian, Xiaoxiang Study, and Jinjiang Literature City.

The writers are mostly in their 20s and 30s, and have all made a splash in the Chinese literary scene, either winning prestigious awards or gaining large fan-bases. But the majority of them have only had one or two short stories translated into English in anthologies or journals with a relative limited circulation. They come from a variety of backgrounds: Anna Wu and Xia Jia have degrees in literature, but Shen Yingying is a physician by training who started writing short stories and novellas online at the beginning of this century, the popularity of which led to the offline publication of five of her longer novels. Wang Nuonuo graduated from Cambridge University with a degree in economics and was a Key Opinion Leader (China’s equivalent of influencers) on Q&A platform Zhihu before she started writing science fiction.

Over the past 30 years, the internet has given rise to a number of prominent female authors. In an essay on web novels that comes at the end of the anthology, sci-fi writer and translator Xueting Christine Ni points out that China’s mainstream publishing industry has been dominated by men since the 1950s, and strongly favors male authors. ”Entrenched patriarchal attitudes meant that they [women] were still expected to take the share, if not all, of domestic and childcare responsibilities,” writes Ni, giving them neither the time to write or the respect required by senior management in publishing houses ”to raise them out of the ever-growing slush pile.”

But since the early 2000s, online literature platforms have helped female authors in China, many of whom started as amateurs, bypassing biases from publishers and readers to break into genres previously dominated by men. The voting, rating, and subscription systems on these platforms, largely meritocratic, reward writers based on their popularity with readers instead of credentials.

Excellently translated, the anthology is a refreshing blend of stories, each rooted in China’s classical texts, culture, or worldview. Although fantasy and sci-fi in China have had a reputation in the past of channeling ideas from Japan or the West, this collection takes us to imaginative worlds marvelously different from our own, many with a uniquely Chinese flavor. The anthology’s namesake, “The Way Spring Arrives” by Wang Nuonuo (translated by Rebecca F. Kuang), amalgamates familiar names of gods and animals in Chinese mythology with a puppy love story to present an epic change of season. It starts with Goumang, a boy who follows his crush Xiaoqing on a journey to bring spring to the world. They ride on Kun, a giant fish, bringing the warm currents heated by Zhurong, the god of fire, and Chisongzi, the god of rain, from the South Sea to the North Sea. Rain falls along the way, and the giant fish adjusts the Earth’s axis at their destination, thus beginning spring.

Others fuse traits of both East and West. Anna Wu’s “Restaurant at the End of the Universe: Tai-Chi Mashed Taro” (translated by Carmen Yiling Yan) also puts a new spin on a name recognizable to a lot of Chinese readers. Wu riffs on the essay “Gazing upon the Snow at the Pavilion at the Lake’s Center” by the Ming dynasty scholar Zhang Dai, which documents a serendipitous encounter on the West Lake of Hangzhou. Zhang is a familiar name to Chinese readers, as his essay is required reading in middle school. His background is also common knowledge, a libertine in his early years and a sorrowful old man after the Manchu invasion of 1644. Wu mixes Zhang’s story with the British author Douglas Adams’s Restaurant at the End of the Universe, the plot involving some mashed taro delivered across time and space to the West Lake, ordered by a mysterious man that meets Zhang at various points of his life who helps him travel back in time.

Some use their backgrounds outside of writing to striking effect. “Dragonslaying” by Shen Yingying (translated by Emily Xueni Jin) is set in a shared fictional world known as “Cloud Desolate,” created by Shen and other writers. Su Mian, a female doctor, travels to the southern shore of the Cloud Desolate continent to watch dragonslaying, an operation that splits the tails of jiaoren, sea creatures with the upper body of a human, and turns them into walking beings who will serve humans. Shen’s knowledge of medicine and surgery meshes with the detailed descriptions of operation procedures and the jiaoren anatomy. The protagonist’s desire to prove herself better than male doctors perhaps also reflects the author’s own.

In addition to short stories, the English version of the anthology also includes essays by translators of some of the stories, reflecting on the translation process. For example, Yilin Wang explains a number of choices she made during translation, including her decision to use the pronoun “they” for a protagonist who is a eunuch. Rebecca F. Kuang illustrates her inner debate on translation: staying true to the original text risks making it exotic or “other”; but if a translator renders a work accessible to an audience not familiar with the cultural context, it could also erase the unique qualities of the source text. There are “no good answers or hard-and-fast rules,” observes Kuang, but translators must always “carefully consider who they are writing for, and how they represent a culture that is not their own.”

Interestingly, while The Way Spring Arrives and Other Stories has received a rating of 8.3 out of 10 on reviewing platform Douban, a small number of readers who gave a low rating state they are “disappointed” because “[the content] doesn’t have anything to do with women,” and accuse the book of not being “feminist enough.” Indeed, most of the stories in the collection do not feature gender equality as a central theme, nor do all of them spotlight heroines.

Is it a necessary task of a collection of sci-fi and fantasy stories with a female and non-binary team of creators to spotlight gender issues? ”I don’t think the definition of feminism should be viewed so narrowly, nor do female creators automatically equate to what is expected of ‘feminism’ (especially in the Chinese context),” Emily Xueni Jin writes in a message to TWOC.

The anthology’s writers take different standpoints on the importance of their gender in their creative process. During an interview with media platform Quanxianzai, Wang Nuonuo said that as a “female sci-fi writer,” she found the term “female“ the least significant part of the label. However, sci-fi author Gu Shi, herself a researcher at the China Academy of Urban Planning and Design, feels a responsibility to create ”more powerful female figures” so that young readers will know that women are not just wives and mothers but also ”architects, urban planners, scientists, and astronauts”—as she told the audience at a book launch event in February 2022 at Beijing’s Inside-Out Museum.

For Jin, that these writers are being platformed at all is the main point. “We as the minorities can have a voice and opportunity to make money. Together we break the status quo where male writers have an absolute dominance in Chinese sci-fi translated for an overseas audience. That’s definitely a way in which feminism could take form.”

Corrections: This article has been amended to reflect a mistake in Yiling Wang’s name and replacing incomplete statistics from Publishers Weekly's translation database on the numbers of works translated from Chinese in 2021.