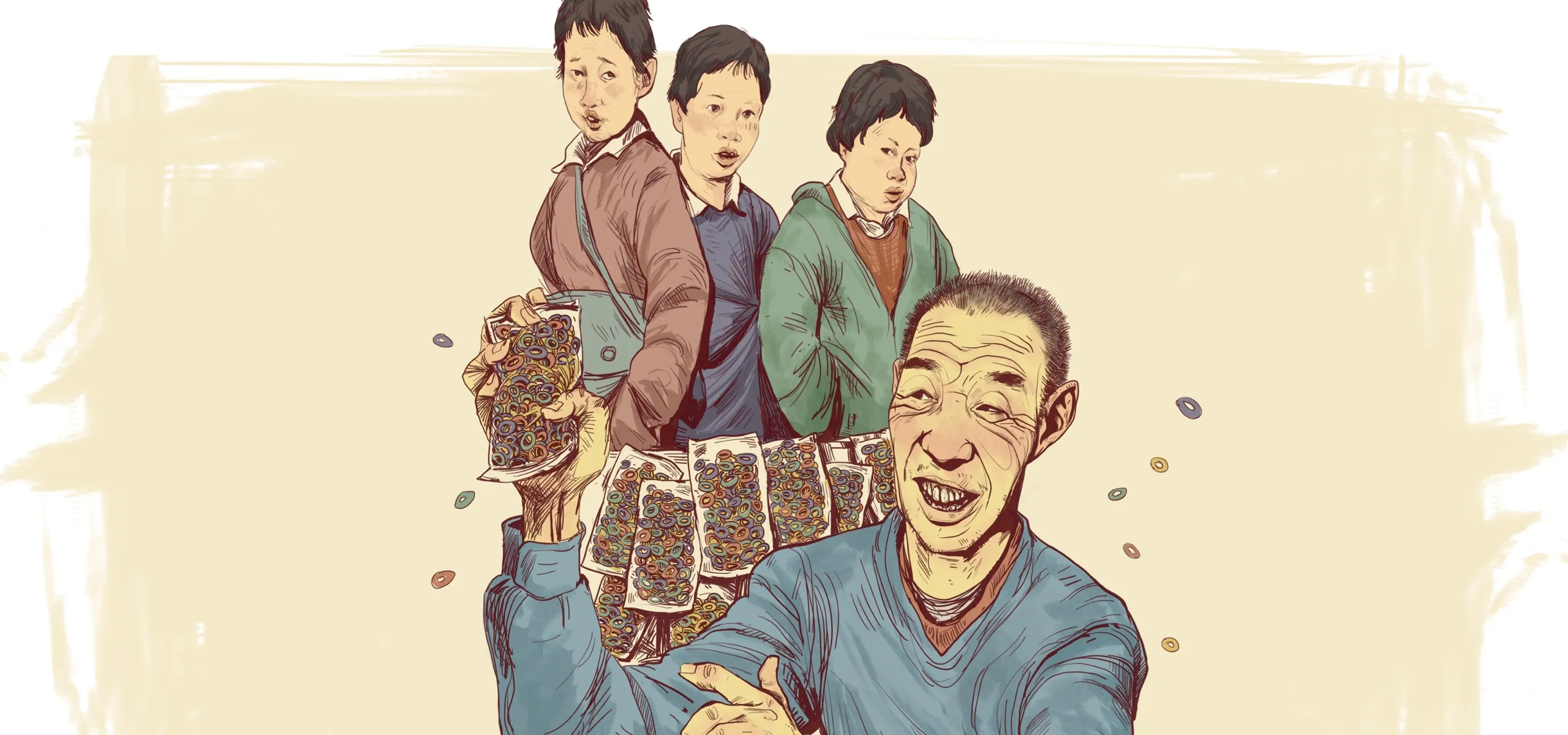

An old man and a mysterious snack set the scene for this cynical and humorous tale by Zheng Zaihuan

Hi-Lee-Bon, Hi-Lee-Bon jumpin’,

Jump right up and land in a coffin

— Schoolyard Rhyme

Hi-Lee-Bon was a snack.

Zhang Guodian was an old man.

Zhang Guodian sold Hi-Lee-Bon.

Back then, we were young. We were so young we didn’t have two coins to rub together. Zhang Guodian set up shop by the school gates, his ratty tarp covered in colorful packages that drew every pair of needy eyes. We knew the names of everything he sold, even if we’d never tried them. Only the rich kids got to try some of the fancier stuff. He had a policy of swapping out anything that wasn’t selling well. Once it was gone, we might never see it again. All of us kids were raised by our grandmas, so we never had an easy time shaking down adults for spending money. When we got some change together, we would always go for the bestsellers. We knew those had to be good. We couldn’t risk getting a dud.

When we saw Zhang Guodian lording over this treasure trove of snacks, we imagined he must be a very wealthy man, though his clothes were worn. There were four people selling things in the school. Two of them were related to teachers. They rented rooms on both sides of the main gate. The other two were Zhang Guodian and Baoshan, who laid out tarps on the other side of the gate. Baoshan was a young guy. He wasn’t much of a talker. Zhang Guodian was the opposite. As soon as he saw a potential customer, he’d start making his pitch.

“Spend it or lose it,” he would say, if he saw a kid overthinking their selection or hesitating to part with their hard-earned money, then he’d go back to talking up whatever the hottest items were. His personal favorite was Hi-Lee-Bon.

“Hi-Lee-Bon, crick crack zoom,” he would rap. “Bump and jump across the room. Might jump all the way to North Korea. Like Jiguang when he got in the way or Cunrui when the pack went boom.”

He switched the lines each time. We were never quite sure what he was talking about. But it was fun to repeat. It was cool. That one with the lines about war heroes spread really fast. We had all read in our school books about Huang Jiguang sacrificing himself in the Korean War and Dong Cunrui’s heroic suicidal attack on the Nationalists. They were people to respect. For Zhang Guodian, associating them with Hi-Lee-Bon was a marketing masterstroke. With all the work he was doing to sell them, there weren’t many people left at our school that hadn’t tried Hi-Lee-Bon.

They were circular, multicolored discs of crispy deep-fried batter, although I forget now what kind of bag they came in or even what they tasted like. I don’t even remember why it was called Hi-Lee-Bon. At this point, probably nobody knows. All I can remember is that they weren’t anywhere close to as tasty as the other bestsellers. Any kid that’s ever tried Spicy Stix or Gummi Juice has that flavor permanently carved into their memory—and you can still go out to a supermarket and buy them. If it wasn’t for Zhang Guodian’s patter, I don’t think anybody would have tasted Hi-Lee-Bon. There were plenty of other snacks from that time that nobody remembers. They disappeared. But we remember Hi-Lee-Bon because of Zhang Guodian.

A little while ago, I was on the phone with an old friend, Ma Hong, and asked him if he remembered Hi-Lee-Bon. He laughed and repeated that rhyme—“Hi-Lee-Bon, Hi-Lee-Bon jumpin’, jump right up and land in a coffin”—and asked me what made me think of Zhang Guodian.

It’s true, Hi-Lee-Bon and Zhang Guodian became synonymous. You couldn’t mention one without the other.

Zhang Guodian was the only one selling Hi-Lee-Bon. He seemed to have a steady supply of it, but none of the other three vendors were able to get their hands on it. We never found out why until after the accident. You see, it turns out—

Hold on. I’m getting ahead of myself. Before we get to the final blow, I have to tell you about two incidents that happened before that. They were both pretty bad, even if they weren’t fatal.

The first incident had absolutely nothing to do with Hi-Lee-Bon.

We all liked Zhang Guodian. He had a lot of life in him. He didn’t seem like all the other adults we knew. We knew we could joke around with him like a kid our age and he wouldn’t pull seniority on us and show us his adult face. When school let out, there used to be a group of people hanging around in front of his tarp. He didn’t care if they were buying or not. We just liked listening to his patter. We even tried a couple times to gang up and steal from him. We had someone create a distraction, then we tried to grab what we could. It never worked out. He was wise to the whole thing. But he never made a big deal about it. He knew what hungry little beggars we were. He knew we didn’t have any money. What was he supposed to do? He earned his living from us, as broke as we were. He did his best to treat everyone the same. Even his grandkids didn’t get free snacks.

I once saw a particularly clever and broke first grader snag a free piece of Spicy Stix, though. What happened was that an older kid had dropped it on the ground. He’d just bought it a few seconds before. All he could do was gaze down at his Spicy Stix, freshly powdered with road dust. Of course, he could have grabbed it and rinsed it off at the faucet by the gate, but he didn’t want to stoop to that level. He could only sigh.

When it happened, we were leaning against the wall, talking about whatever we were talking about, and trying to keep an eye on the Spicy Stix. It shouldn’t have mattered to us, but we couldn’t peel ourselves away from it. The first grader came by and spotted it, too. I remember he even shrieked. He was about to run over and grab it, but something made him wait. He noticed that we were all staring at him. He knew it wouldn’t look good to eat food off the ground, so he decided to bide his time. He took out a piece of chalk and started drawing stuff on the ground. A little while went by and the next thing we knew, he was running. The Spicy Stix was gone.

All we wanted in the world was snacks. We could never imagine that one day someone who was rich enough to buy snacks by the crate—and share them with us—would strut through the school. But that’s exactly what happened.

He was a first grader, too. He had started school earlier than he was supposed to and always looked a bit underfed. His name was Hu Sixiang. It was his bad luck that his name could be turned into an unflattering four-character phrase by adding a single word: husi luanxiang—someone that lets their imagination run wild. That became his nickname, even though he didn’t have much of an imagination at all. He only cared about spending money. His dad was a doctor. We hated his guts because he was the guy that gave us all our shots. He always lied to us: “No, it won’t hurt at all.” We all knew it was going to sting like hell.

Doctors must make too much money, otherwise they wouldn’t leave a bundle of cash lying around where a six-year-old could get their hands on it. That was a wild day. There were wrappers all over the schoolyard. Once we got let out, everyone rushed over to Hu Sixiang’s class and surrounded him. They were on him like flies on feces. He was like some kind of ancient child emperor. The way we paraded on both sides of him, a hundred yuan note was better than any crown.

The first time we saw the bill, we all thought it was fake. What could a kid like him be doing with all that money? He was spending it as fast as he could, of course. He went to Baoshan first. Baoshan could tell the note was genuine, but he wouldn’t touch it. He knew it had to be stolen. He figured there was no way the kid’s parents would have sent him off to school with that much cash. When Hu Sixiang saw that he wasn’t going to be served, he went over to Zhang Guodian, who was more than happy to sell him what he wanted. “I’ll take your money,” Zhang Guodian said, “but make sure you buy some extra Hi-Lee-Bon.”

“How much can I buy?” Hu Sixiang asked.

“Buy as much as you want,” Zhang Guodian replied.

We feasted on Hi-Lee-Bon that day. Zhang Guodian couldn’t make change for a hundred, so he had to borrow some smaller bills from Baoshan.

“You’re going to regret this,” Baoshan said. “He stole that money.”

“How would I know?” Zhang Guodian said. “He has money and I have product, so I’m going to sell it to him. That’s not against the law.”

Baoshan kept his eye on the situation but all he saw was Zhang Guodian raking in more cash. Hu Sixiang had no concept of what the money was worth. Once it was spent, he went home to grab more. He passed the money around, paying off runners to go get him stuff. He was getting fleeced, but he didn’t care. He was just happy to be spending it. Baoshan and the other two vendors finally gave in. They prepared their stock and waited for the money to run out. They figured it wouldn’t last forever and Hu Sixiang would be discovered, so they might as well cash in while they could.

Hu Sixiang’s parents arrived at the school a week later. They had found a stash of illicit cash in his backpack. They interrogated him in front of all the teachers and students. In seven short days, he had managed to burn through 800 yuan, minus the bit that was in his bag. His parents suspected that someone had swindled him. But everyone they asked had the same story: Hu Sixiang had spent it on snacks.

His parents were furious. They went with the teachers to talk to the snack sellers. The teachers’ families were tipped off, so they shut down shop and hid inside, but there was no way for Zhang Guodian or Baoshan to escape. All they could do was wait to be interrogated.

“Why did you sell him all that junk? You saw how much money he had. Why didn’t you tell a teacher? Do you two know what it’s like to raise kids?”

Zhang Guodian and Baoshan said nothing. They looked like kids being lectured by a stern teacher. Baoshan wasn’t much of a talker at the best of times, so it was no surprise to see him keep his mouth shut. He looked about as animated as a chunk of wood. Zhang Guodian smiled apologetically. When the mother had finished her lecture, he said cheerily, “If your family wasn’t so rich, I bet none of these kids would have gotten to see a hundred yuan bill!”

“We earned that money,” Hu Sixiang’s mother said. “Unlike your son, we don’t have access to government funds. I’m sure he didn’t think twice, burning through all that money.”

Zhang Guodian was taken aback. His warm expression froze solid. He didn’t say another word.

Hu Sixiang’s parents lit into everyone in turn. They were an educated family, so they had a way with words. They managed to make everyone feel ashamed for what they had done and fearful of the consequences. When they were done, they took Hu Sixiang home. He was transferred to another school the next day. I never met anyone as generous as him. It turned out that Hu Sixiang’s parents had just lost their firstborn son, so they didn’t want to take any chances of our bad habits rubbing off on their second.

I’d seen the older brother one time. His name was Hu Lixiang. He’d gotten rabies from a dog bite. His parents kept him shut up at home. He was irritable, scared of water, and always on the verge of losing control of himself. One day, he got out. He was running around naked out in a field. It had been so long since he’d been outside that he was unable to contain himself. We saw him on our way to school and started tossing chunks of mud at him, then dragged him with us to school and told him to run into the girl’s bathroom. He got carried away. He was in a state of euphoria. When we went into class, he stayed out in the schoolyard. I caught sight of him later when I got up to read. He was sitting out on the ping-pong table, swinging his legs. I got up later to check if he was still there, but he was already gone.

Right around the time we were getting out of class, it started raining. The next day, we heard he was dead. He had drowned in a pond out in a field. The rain had come down so hard that the fields were flooded. He had been running around, trying to get out of the rain, but he ended up in the pond. He’d put up a good fight. He lost.

Zhang Guodian and the rest of them won. They had made more in a few days than they made most months. The principal called a meeting of the teachers and asked them what they thought about the snack sellers. He asked if they should be banned. It was a tight-knit community, so nobody was willing to out themselves as being against them.

“Every school has snack-sellers,” one of the teachers said. “They don’t all have a Hu Sixiang.”

Zhang Guodian went back to selling his Hi-Lee-Bon. There weren’t going to be any more customers like Hu Sixiang.

The second incident had something to do with Zhang Guodian’s son.

He only had one.

He was proud of him.

He’d planned to send his son to technical school. To cover his tuition, he used the money he made selling his cattle. He had been at it for twenty years and raised four heads. The first had been a calf that he’d picked up under a bridge over a field. He had no idea why anybody would abandon a calf out there, but he figured maybe she had run off or a thief had been trying to make off with her and had hidden her there. When he found her, he had been crossing the bridge and felt nature call. He shimmied down the bank to do his business and saw her there. He was always thankful for that pressure on his bladder. He thought it must be fate. His heart was beating so fast that he couldn’t even crouch. He grabbed the calf and took her home. She grew into a healthy heifer and got pregnant a few years later. She gave birth and he raised the calf up until it was old enough to take to market. A few years later, he sold off the old heifer and kept one of her calves.

He went on that way, in a five-or-six-year cycle, raising a cow until she gave birth, selling her off, and keeping a heifer. After so many years, he got used to having his cows with him, and all the chores that went along with it, like storing up fodder and shoveling manure. The year his son—Zhang Liang—went to school, he sold off the cow and whatever feed he had left.

Zhang Liang took the money and vowed to someday make enough to buy another cow. He finished school, got a job, got married, had a couple kids, and finally ended up working as an accountant for the municipality. After he was accused of embezzling funds, Zhang Liang ran away. Not only did Zhang Guodian not get a cow, but he lost his son.

He ran away, leaving a son and a daughter, a bad-tempered wife, and an unfinished house. The contractors didn’t get paid, so they dragged off whatever building materials they could salvage. What was planned to be a two-story house standing proudly at the entrance to the village was left a shell, with its top floor perpetually incomplete. Since it was close to the highway, drivers would pull over and use it as a public toilet. It quickly became covered in urine and excrement. The place stank. What should have been the most beautiful home in the village became a ruined husk.

The municipal government had ordered it left where it was, standing as evidence of Zhang Liang’s crimes. He had stolen enough money that there were reports circulating about it online, in addition to the local announcements offering a reward for information of his whereabouts. He wasn’t able to come back for a long time. I don’t know if the reward had an expiry date, but he wasn’t going to take the chance of coming back before then.

Zhang Guodian didn’t know where his son had gone. He had a vague idea that he must have headed south, since, if anyone ever left the village, that seemed to be where they were drawn. Zhang Guodian himself had never been anywhere but to the county town. He knew that the Nanguan Hospital was on the southern edge of it, and the Nanguan Penitentiary was there, too. Further south past that, though, he had no idea. Before going on the run, Zhang Liang had gone to the school to see his father. He had told him to keep an eye on his wife, Yanling. “Make sure she doesn’t run off,” he had said. There hadn’t been much time to talk, so Zhang Guodian had reassured his son. He told his son that he should make a run for it and he’d look after Yanling.

That was easier said than done, as he realized after Zhang Liang was gone. There’s no woman in the world that wants to wait around for a man who’s not coming home. Yanling was definitely no exception. She was a flirt. She was pretty, too. She wasn’t afraid of anything. The only thing she couldn’t stand was being alone. In the first few days after his son went on the lam, Zhang Guodian was constantly on guard, worried that he would return home one day and find her gone. People talked about Yanling like they talked about Zhang Liang. He’d have to hear about her running off or about who she was sleeping with. Someone would come over and give him the sad news, as if they were gossiping about someone he didn’t really know.

To make it easier to keep an eye on Yanling, Zhang Guodian suggested that she move in with him. She accepted. She didn’t stay for long, though, before making an excuse and moving out again. She picked up a job planting trees in the city, trying to earn a bit of extra money. She worked in construction in one season and picked tea in another. She left early in the morning and came home late at night. Sometimes, she’d even be gone for a couple of days. She would drop her kids off with their grandmother. She spent money as fast as she made it. She liked to drink, especially when she was playing mahjong. Whenever she was gone, Zhang Guodian was never quite at ease. He was worried that she would do something shameful or that she might decide not to come back at all. One day, he couldn’t take it anymore, so he asked her if she was going to end up running away from home, like Zhang Liang.

“What do I have to run for?” she spat. “What fucking law did I break?”

Her answer didn’t do much to reassure Zhang Guodian, but it turned out he didn’t need to worry. Even after the accident, when it fell to Yanling to support the family all by herself, she never ran away. She stayed. She raised her two kids there. She buried her mother-in-law there. Zhang Liang never came back, even if there were rumors that he might have visited once or twice. Nobody knew for sure. As far as most people were concerned, he didn’t mean anything but a chance to cash in on the reward for turning him in. There was still a decent price on his head. If he had come around again and someone got wind of this, they wouldn’t have turned a blind eye. They were waiting for him, just like Yanling was, even if their reasons were different. She got old waiting for him. She waited for him until she wasn’t beautiful anymore. But she never ran away.

“What do I have to run for?” she said. “What fucking law did I break?”

The third incident did involve Hi-Lee-Bon. In the end, it was a tire that sent him to his coffin, but it started with Hi-Lee-Bon.

That was a scary day. A kid keeled over on the schoolyard, twitching and foaming at the mouth. The teacher that ran over thought the kid was having a seizure. He yelled for someone to get a stick to stop the kid from biting off his tongue. But right then, another kid keeled over. You could tell that they were in pain. Both of them were throwing up half-digested food—and both of them had clearly eaten Hi-Lee-Bon, since we could see the multicolored shreds of it in the vomit. There was no doubt about it. The common thread was Zhang Guodian’s Hi-Lee-Bon.

“Food poisoning,” the teacher declared.

The school called an ambulance. The teachers had already figured out the link between the sudden illness and the Hi-Lee-Bon. They gathered around all the kids and asked who had eaten them. The students that had eaten them got loaded into the ambulance to get checked out. Not quite a dozen kids were taken in. Zhang Guodian watched the scene with his lip trembling and his legs shaking. After the ambulance left, the principal seized the rest of the Hi-Lee-Bon and brought him into his office. All the kids were hanging out at the windows, peering in. Trying to prove that the Hi-Lee-Bon were not to blame, Zhang Guodian, started ripping open packs and eating them. The teachers couldn’t stop him.

“Why would you say there’s something wrong with them?” Zhang Guodian said, his mouth full of half-chewed Hi-Lee-Bon. “There’s nothing wrong with them! I swear on my grave. They’re fine!”

“Nobody’s blaming you,” the principal said. He was a fat man. “We just need to wait for the police to come and we’ll clear this up.”

The police took away Zhang Guodian and his Hi-Lee-Bon. They noticed that the expiry dates on the packages had passed a year before. It was evidence of a crime. The two children that had keeled over in the schoolyard turned out to be fine, but they stayed in the hospital a few days, just to make sure. We were all jealous. At that age, most of us had never been to the county town, let alone the hospital.

At the police station, Zhang Guodian revealed the source for his Hi-Lee-Bon: A traveling salesman had learned that he sold snacks and drove over to his house with a trunk-load of Hi-Lee-Bon. They were already close to the expiry date, so Zhang Guodian got a good deal on them. He figured he might as well try to turn a profit.

“I thought I could sell them before they expired,” Zhang Guodian said. “I asked Baoshan and the rest of them to go in with me on them, but they didn’t want to. They figured I was going to screw myself. That’s exactly what they wanted. But I had no problem selling them. It broke their hearts. They wanted to get a piece. But I was stubborn. You ever heard the saying, a good horse won’t turn back to get a patch of grass? I might not be a good horse, but I don’t turn back. I didn’t sell them any. I didn’t think it would be a problem if they were a couple days expired. I fed my grandson a pack of them every day. I figured, as long as he was fine, I was okay to sell them.”

“You tested them on your grandson?”

“He loved them,” Zhang Guodian said.

He paid a five hundred yuan fine and went home. He showed up at school the next day. He didn’t have any Hi-Lee-Bon with him. He found the gates to the school barred. Baoshan told him that they had held a meeting and voted unanimously to ban him from selling snacks.

“They said you’re a bad man,” Baoshan said. “You were willing to do anything to make money.”

“It’s all your fault,” Zhang Guodian said. “Don’t think I don’t know what you did.”

“What did we do?” Baoshan demanded. He shouted, so that the sellers in the rooms beside the gate would hear him, “Missus Wang,” he said, “Miss Cai, what did we do? Tell me.” There was no answer.

Zhang Guodian boiled over with rage. His lips trembled with fury.

“You know exactly what you did,” he said.

That was Zhang Guodian’s final statement in front of the school gates. That was the last time he showed up there. We never saw him again. We even forgot about him—until we heard that he had died. When we heard how it happened, we couldn’t help but think of Hi-Lee-Bon. We couldn’t help but think of that rhyme about the coffin.

It was a tire that killed him. The tire was already off its axle when it hit him, but it was still spinning.

When he left the school after his confrontation with Baoshan, Zhang Guodian had gone home and dumped the Hi-Lee-Bon in the river. He had been planning to let his grandson eat what was left over, but he was too furious to keep it around. When we heard what he’d done, we rushed downstream. We figured we could fish out some free Hi-Lee-Bon. But Zhang Guodian had been in a mean mood when he’d dumped them, so he made sure to rip the packs open before tossing them in the river. We found plenty of empty packs but only a few mushy, tasteless Hi-Lee-Bon.

Zhang Guodian was willing to give up on Hi-Lee-Bon, but he couldn’t shake the entrepreneurial bug. His house wasn’t far from the highway, and the county market was pretty close, so he set up a new shop out front. He figured there would be enough people driving or walking by. There were enough to keep him afloat, at least. His customers were no longer students, so he changed what he was selling. He still liked composing rhymes for his products. Even when people didn’t buy, they might still walk away humming a tune. It seemed like his life would continue in about the same way. There was an old saying: walk into the mountains and a path will appear. A path might have bumps along it, but people get over them. What did Zhang Guodian have to worry about? He’d been down many roads and over many bumps.

That old saying didn’t mention tires.

Around lunchtime one day, Zhang Guodian went to the side of the road to set up his products on his tarp. When he was done, he sat down on his stool to wait for a customer. It was a lazy summer day and nobody was out and about. Zhang Guodian let his mind wander. The sound of a truck rumbling toward him didn’t rouse Zhang Guodian. He had lived beside the highway too long to pay any attention to the sound. I hope he was asleep. Maybe he just shut his eyes and never woke up again. Maybe he never saw the tire fly off the truck and come hurtling toward him. By the time the truck tipped over and smashed into the pavement, Zhang Guodian was already dead.

When the news reached our school, we almost died laughing. The way he died was bizarrely hilarious to us. Someone made up their own rhyme about Hi-Lee-Bon, mimicking his old sales patter: “Hi-Lee-Bon, Hi-Lee-Bon jumpin’. Jump right up and land in a coffin.” It was funny to us. The rhyme wasn’t as good as anything Zhang Guodian might have come up with, but we all remembered it. We would sing it whenever we told the story of Zhang Guodian.

So, now you know.

Hi-Lee-Bon was a snack.

Zhang Guodian was an old man.

Zhang Guodian sold Hi-Lee-Bon.

Author’s Note: I believe this story was written in 2013. Before, I didn’t have the habit of putting a date on my writing, as it felt too deliberate—I prefer to use my memory. I thought I could remember everything, but of course, I can’t. This story was a process of recollection, not with exact dates, just a few vague clues: about a snack whose taste I forgot; an old man with a vivid personality; a period of my childhood filled with hunger and desire. The snack died out; the old man was killed by a tire; and the left-behind child grew up to be a young rover who has been hit by bigger tires. He reaches back into his memories, and a story forms. He pushes the tire back down, and dust rises.

Zheng Zaihuan 郑在欢

Born in 1990 in rural Zhumadian, Henan province, Zheng dropped out of school at the age of 16 to work in a luggage factory. He started writing while working 12 or more hours per day, often at midnight or in the early morning after his shift’s end. With humor and insight, Zheng wrote about his rough childhood, experiences at school, hardships, and the people he encountered. His first short story collection, Sad Stories from Zhumadian (《驻马店伤心故事集》) , was published in 2017. His latest works, Kill the Enemy All Night (《今夜通宵杀敌》) and Reunion before Parting (《团圆总在离散前》), both short story anthologies, came out in late 2021.

Hi-Lee-Bon | Fiction is a story from our issue, “Sports for All.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.