The “Lin Lan Fairy Tales” was a huge project, collecting folklore for children from all across China. So why has no-one heard of it?

“I think every post-80s kid [in China] grew up with Grimms’ Fairy Tales,” Chen Qingqing, a 36-year-old graphic designer and mother of two from Tianjin, tells TWOC.

This is a strange contradiction: China has perhaps the richest trove of historical legends, mythological stories, and tales of the strange and fantastical of any culture, yet it is collections of 19th century German fairy tales that top best-seller lists on major Chinese e-commerce platforms. The most popular translation of Grimms’ Fairy Tales, by German Studies scholar Yang Wuneng in 1992, has been reprinted at least 20 times and sold millions of copies, according to a 2013 paper in the translation journal Babel.

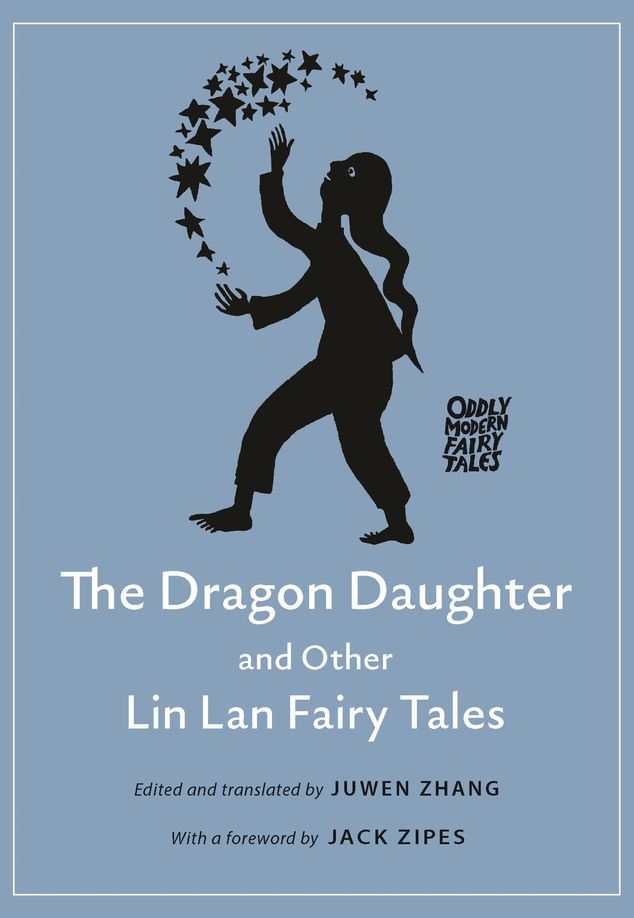

The relative failure of Chinese fairy tales to gain widespread popularity is not due to lack of content: From 1984 to 2009, the Ministry of Culture collated 30 volumes of traditional Chinese folktales, amounting to many thousands of stories, for its Chinese Folktales Collection. Further evidence of the untapped well of China’s homegrown traditional canon is provided in the Princeton University Press’s newly published The Dragon Daughter and Other Lin Lan Fairy Tales, an eminently readable collection of 42 fairy tales, most of them translated into English for the first time.

These stories, selected and translated by Juwen Zhang, a folklorist and professor of Chinese Studies at Willamette University, are a rare resurrection of what Zhang called in a 2020 paper the “Brothers Grimm of China.” Lin Lan (林兰) was not a real person, with no backstory to speak of, but is identified as female as some stories attributed to her were signed “Lady Lin Lan.” It was the fictional pen name for a group of folklorists and writers, who together between 1924 and 1933 collected close to 1,000 tales from oral traditions across China.

The 42 stories Zhang has selected from the canon are a delightful blend of the familiar and the strange. There are the usual princesses and evil stepmothers, but the pages also teem with dragon kings, silkworms, ghost weddings, golden hairpins, and celestial palaces.

Some are recognizable versions of stories still in common circulation, such as “The Cowherd and the Girl Weaver”: two lovers separated on opposite sides of the Milky Way, whose brief reunion on one day each year marks China’s own Valentine’s Day, the Qixi Festival.

Other standouts include “Brother Moon and Sister Sun,” a short explanation of why the sun comes out during the day and the moon at night; and “The Paper Bride,” about a man who makes a wife out of paper to fool his uncle (subject of a 2021 video game). Several tales about snake spirits that call to mind “The Legend of White Snake.” All in all, they’re charmingly off-kilter, full of imaginative characters and events like any good folk-story.

But the original creators of these fantastical stories, centuries before Lin Lan, would not have thought of them as fairy tales. “China has had fairy tales since ancient times,” children’s writer Liu Liduo opines in her 2020 anthology Chinese Fairy Tales, “It’s just that those writing the fairy tales weren’t aware of it and children had no opportunity to read them.” Compilations of myths and legends abounded in the Chinese canon, from The Classic of Mountains and Seas (《山海经》) in the fourth century BCE, to Duan Chengshi’s (段成式) Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang (《酉阳杂俎》) in the ninth century CE, to Pu Songling’s (蒲松龄) Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio (《聊斋志异》) in the 18th century.

Such works were written in a classical Chinese only accessible to the literati, although many had their origins in oral tradition mirroring European fairy tales. None of these were meant for children. That would have to wait for modern understandings of childhood and children’s education to develop in the early 20th century alongside the New Culture Movement, which called for modernization of Chinese culture. It was at this time that the word “fairy tale,” or tonghua (童话, literally “children’s stories”), was imported from Japanese, the first translation of Brothers Grimm stories arriving in China as early as 1902.

The New Culture Movement placed a premium on children as the future of a newly-formed Chinese nation-state, lending the matter political importance: “Strength in the youth is strength for the country,” wrote reformer Liang Qichao (梁启超) in his influential 1900 essay “Ode to Young China.” “Wisdom in the youth is wisdom for the country...the progress of the youth is the progress of the country.”

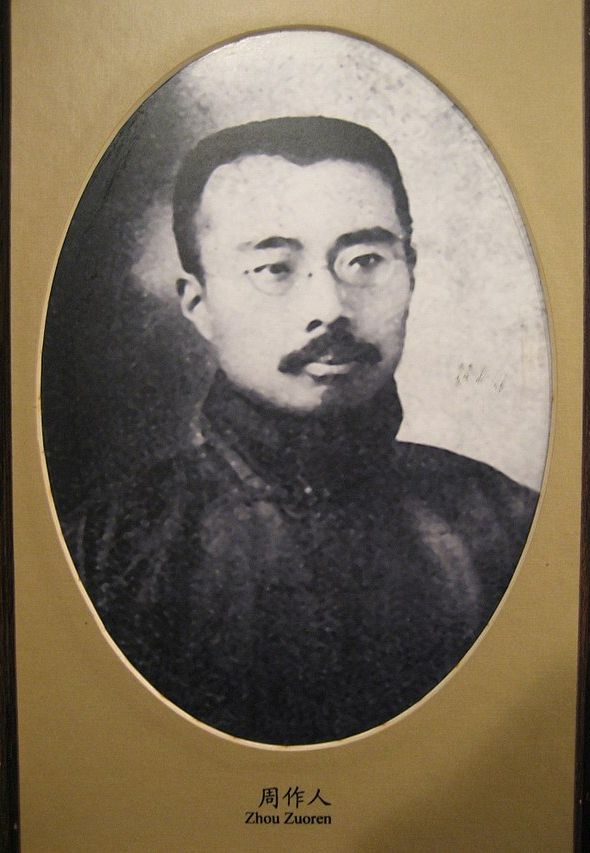

Given the importance of nurturing the national consciousness and literacy of China’s future generations, some intellectuals of the era wanted to reform children’s literature. Zhou Zuoren (周作人), Lu Xun’s (鲁迅) brother and a prominent translator, who coined the Chinese word for “folklore,” complained in his essay “On Saving Children” in the early 1910s of the lack of good Chinese books available to boys and girls, saying “children’s literature in China is brimming with empty words and false emotions.”

Zhou would later become a contributor to the so-called “Lin Lan Fairy Tales,” alongside other leading intellectuals and pioneering folklorists. Their works were eventually published across 43 anthologies, eight of which were fairy tale collections, by Shanghai’s North New Books, the New Culture Movement’s leading publishing house.

Although never explicitly outlined by Lin Lan writers, there is certainly a connection between the work of these folklore scholars and the Brothers Grimm. Indeed, some of the people behind Lin Lan were the very same responsible for first translating Grimm and Andersen, introducing them to Chinese audiences. Li Xiaofeng (李小峰), a student of Lu Xun believed to have created the name “Lin Lan” for the first few stories, also co-translated the first complete Grimm anthology in Chinese in 1932.

Like the brothers, the Lin Lan tales were designed for a mass audience, appearing in the form of oral folktales written in vernacular Chinese.

They were popular enough that many volumes were reprinted three times, and they were read by urban schoolchildren. The project was one of the largest and most influential literary undertaking of its kind. Advertisements soliciting contributions were placed in journals like Tattler (《语丝》, a “new literature” publication that would play a critical role in modernizing written Chinese). Writers gathered accounts from different regions across China—The Dragon Daughter lists tales recorded in provinces like Henan and Hubei, while Sun Jiaxun, a notable folklorist of the time, collected stories from his native Jiangsu province.

The character of oral retelling is preserved in Zhang’s loose and easy translation of The Dragon Daughter for Princeton Press. Several tales appear in the book in multiple variations (just as they had in the original Lin Lan anthologies) no doubt the result of embellishment by generations of speakers in different communities. That these versions appeared together suggests collectors were operating under the Grimms’ admonition to record “authentically,” without censorship or bowdlerization. As a result, much like what the Grimms found in Germany, much of what they recorded is hardly suitable for children—graphic descriptions of murder, monkeys urinating on people, and a horse attempting to rape a woman.

Sadly, given Lin Lan’s aims to serve the masses, the name has faded from memory. By the 1950s and 1960s, there was a society-wide movement to promote science and suppress superstition. The rare stories published during that period that did feature magic portray it as a deceptive trick. Zhang Tianyi’s (张天翼) 1958 classic The Magic Gourd concerns a boy named Wang Bao who obtains an enchanted vegetable able to complete his math homework and grant him anything he asks for. But it turns out the “gifts” granted by the gourd are all stolen from the boy’s classmates, and the story ends with a moral on the value of hard work and the danger of a magical short-cut. The ending also reveals “it was all a dream,” handily avoiding an actual supernatural occurrence.

The post-1978 reform era brought more challenges to popularizing Lin Lan stories. The writers behind the collection had either left the Chinese mainland, or died. The books were hard to read, printed vertically using traditional characters, while Western culture was the new trend. Zhang’s translation is the first comprehensive reprint of the stories since a Taiwanese edition in 1981.

Although there is increased academic interest in Lin Lan on the Chinese mainland, little of her is read by the public. Searching for ”Lin Lan” on e-commerce platforms Taobao or Dangdang turns up nothing but a few pricey listings from rare book dealers or a poorly printed facsimile. To find Lin Lan on library shelves, one has to seek out the North New Book archive materials at Beijing Normal University or Shanghai University. “I’ve never heard of Lin Lan,” Chen tells TWOC. “I read lots of Japanese children’s books to my kids. I want to read more Chinese [stories to them] but can’t seem to find good ones.”

This gap in the market for traditional Chinese fairy tales has not gone unnoticed, with many authors inspired to take up the challenge. Yi Wei, a children’s author who has won the prestigious Bing Xin Children’s Literature Award, spent 10 years starting in the late 2000s collecting some 10,000 folktales from existing anthologies, including Lin Lan. During this time, she read the tales to schoolchildren, noted the ones they enjoyed the most, and curated and adapted them for her collection Chinese Folk Tales (2017).

The book has been a success, already in its second edition. Might Yi achieve what Lin Lan couldn’t? That is for the children (and the children of their children) to decide.