Singing show’s judging standards has netizens petitioning the government to “monitor” it

Produce 101, the Chinese version of the hit Korean idol competition, saw its finale last Saturday night. In this program, audiences vote on 101 young female contestants until 11 are chosen to form the new pop idol group, Rocket Girls.

The top winners, Meng Meiqi and Wu Xuanyi, received over 185 million and 181 million votes respectively, but they’re far from the most famous legacy of the show. That title belongs to Yang Chaoyue and Wang Ju, overnight wanghong whose success on the show have prompted an outcry over the judging criteria Chinese idol contests: Is it about looks, talent, or personality?

Sweet-mannered Yang, a member of girl group CH2, gained recognition among the show’s audience her appearance as well as dislike for her inferior singing and dancing abilities. Yang, who was born in a small village of Jiangsu province, has had several performance episodes on Produce 101 go viral and trigger a trending Weibo hashtag, “car crash singing ability”.

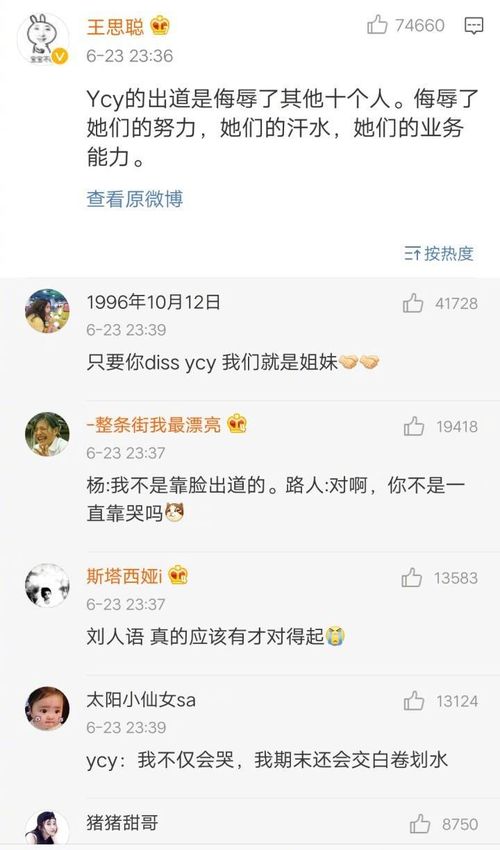

Wang Sicong, son of China’s richest man (and professional troll in his own right), has also dissed Yang:

Yang’s debut is an insult to the other 10 contestants, an insult to their hard work, their sweat and their professional competence” (Weibo)

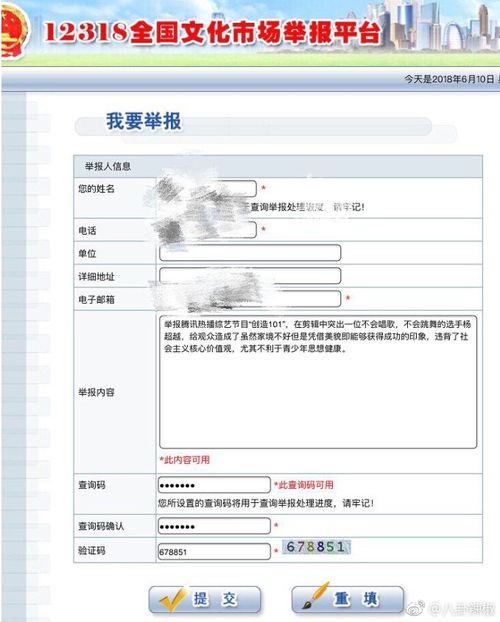

A few netizens even anonymously reported Produce 101 to the National Cultural Department, appealing to Chinese government to “monitor” this TV show. Their claim is that Yang “gravely violates the socialist core values,” since she does not have any singing or dancing talent, being only a doll-like girl.

(Weibo)

On the contrary, Yang’s adoring fans give her much encouragement and a nickname, the “Village Flower” (村花).

“We know how hard you are working and we will always support you. Trust yourself and you are the most shining star!” (Weibo)

In contrast to Yang, Wang Ju isn’t in trouble because of her generic good looks—just the opposite, in fact. Labeled as “old auntie” after her first appearance on the show, Wang is taller and heavier than the other contestants. “Wang Ju is chunky and dark. I’ll never vote for her.” one audience member told the Guardian, which has called Wang “China’s Beyonce” and applauds her break from traditional beauty standards.

Wang has addressed these challenges directly: “Some people say girls like me cannot be idols. But what exactly are the standards for being a girl idol? I’ve eaten up all the standards,” she said after a performance in May. Though some netizens have dug up old photos of Wang, when she was younger and slimmer, Wang has stated she has no wish to go back. “The standard of being beautiful is to be yourself.”

(Weibo)

Owing to her frank personality, numerous fans have bought Wang’s “unorthodox style.” “I believe that we always lack a female role model who is confident and dares to challenge conventional standards.” Echo Wu, an interior designer based in Beijing, told the Guardian.

Ironically, it was a 2005 song called “Sing If You Want To” (想唱就唱), played on every street and alley of China, that ushered in an era when the grassroots talent shows first became popular in China. The breakout success of Hunan TV’s singing contest Super Girl (超级女声) was impetus for Chinese television industry to realize the considerable potential (and money) in voter-based idol contests. And in 2006, Super Girl had given birth to an early mainstream female celebrity who challenge the conventions of beauty in China: Li Yuchun (李宇春), who won the show in spite of (or because of) her tomboyish appearance and unique music style, and remains popular as a singer as well as role model today.

Another unconventional performer, Peking Opera artist Wang Peiyu (王佩瑜), who has participated in iQiyi’s youth talk show Who Can Who Up and a variety of other programs, engages in playing laosheng ( 老生), or old male roles, on the small screen in order to propagate traditional arts among young people. Undeniably, pop idols that subvert beauty and entertainment archetypes exist in China, but not all mainstream shows—or viewers—have caught up.

When it comes to the criterion for Chinese female idols, Sun Li, chief director of Produce 101, has said: “Young people now have independent tastes and judging principles. We will let them decide.” It’s is impossible to cater to everyone, of course, and there is no fixed yardstick to evaluate a performer’s success, but repeated media wrangles about cookie cutter idols—as well as idols who are just the opposite—suggest the criteria may need fixing.