The campaign to replace traditional characters with a phonetic system reflected Chinese society’s desire for change during the 20th century

Many Chinese are proud of their language. The characters, which convey both sound and meaning, have thousands of years of history and are the basis for the ancient art form of calligraphy. But there was a time in the not-so-distant past when some of the country’s most prominent intellectuals wanted to abolish them.

“Chinese characters are truly the world’s filthiest, most vile, and most despicable. They are like a medieval cesspool,” wrote Qu Qiubai (瞿秋白), a leader in China’s early communist movement, in 1931. Later that decade, Lu Xun (鲁迅), one of the most prominent figures in modern Chinese literature, likened Chinese characters to tuberculosis spreading among the masses. He argued that if not irradicated, they would bring about the country’s demise.

Today, such remarks would probably trigger uproar on social media, but they were common sentiments in the early 20th century when intellectuals launched a movement to abolish Chinese characters. They hoped that eliminating the characters would solve China’s illiteracy problem. In 1891, scholar Song Shu (宋恕) wrote that around one percent of men and approximately one in 40,000 women in China could read.

However, the movement also reflected deeper societal and political shifts in the country at the time. Many intellectuals believed the Qing government’s isolationist policies had left China burdened by feudal traditions, while foreign forces increasingly encroached on the country’s territory. The New Culture Movement, born out of a desire to modernize the country, criticized traditional Confucian values and promoted ideas imported from Western countries, such as advanced science and democracy.

Intellectuals like Lu Xun also promoted vernacular Chinese (白话), rather than the archaic traditional form of writing. They saw Chinese characters not only as symbols of the country’s backwardness but also as real barriers to the nation’s development and modernization.

“Characters lack the vocabulary to convey modern ideas and theories and are a breeding ground for toxic ideas. There is no shame in abolishing them,” wrote Chen Duxiu (陈独秀), one of the founders of the Communist Party of China and a leading figure in the New Culture Movement, in 1918.

Reformers proposed various phonetic systems to replace characters. While today, Chinese schoolchildren and language learners become familiar with the pinyin system that notes the sounds and tones of Chinese characters, the first phonetic system, known as Bopomofo in English, emerged in 1913. It didn’t use Latin letters but instead was a combination of tone marks and basic symbols derived mainly from Chinese characters. This influential system is still widely used in Taiwan. The system is less popular on the Chinese mainland but is still used to mark the pronunciation of each character in the best-selling Xinhua Dictionary.

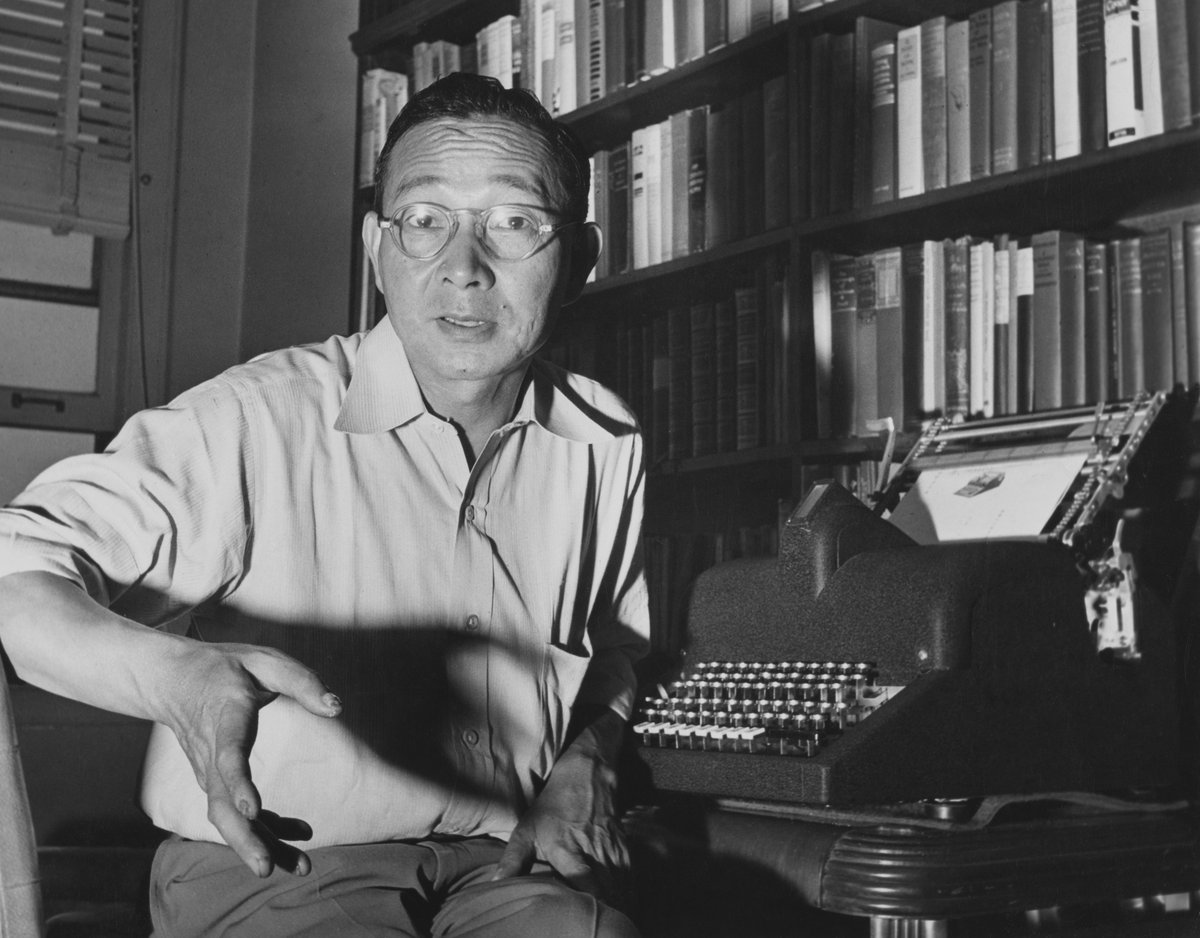

The first system that relied on the Latin alphabet was the Standard Chinese Romanization system introduced in 1928. Initiated by scholar Lin Yutang (林语堂), the system replaced the Chinese-style radicals of Bopomofo with Latin letters, using different combinations to convey Chinese tones. For example, the four tones of “ai” were represented by “ai, air, ae, ay.”

However, the system was complex, lacked official support, and was never widely used. Still, traces of its influence can be found in some current translations of names and locations. For example, the official English translation for 陕西 province is “Shaanxi,” with the “aa” part indicating the third tone.

For a while, the Standard Chinese Romanization system coexisted with Bopomofo, but both were used as phonetic notation methods rather than substitutes for characters. It wasn’t until the 1930s that a Latinized system began to have a serious chance of replacing characters.

Inspired by the Soviet Union’s illiteracy elimination plan, Qu Qiubai proposed the idea of Latin New Script around 1930. The new system eliminated tone indicators and developed different schemes for dialects such as Shanghainese and Wenzhounese. Scholars quickly embraced it. “We earnestly hope that everyone will come together to study it, promote it, and make it a vital tool for advancing mass culture and the national liberation movement,” read a joint statement signed by Lu Xun, Peking University President Cai Yuanpei (蔡元培), and 686 other scholars in 1935.

But by this time the country was divided. The Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911) had crumbled more than two decades earlier, but now the ruling Kuomintang party faced opposition from China’s communists. Qu’s measure was widely adopted in communist-controlled regions, where the communist government declared it legal script. Elsewhere, it was ignored, and its promotion ground to a halt by 1944, allegedly due to the lack of qualified instructors.

Understandably, there was resistance to these moves to eradicate China’s script. “China is a unique ancient civilization with 4,000 years of written records… How should we deal with this cultural legacy after the abolition of Chinese characters? Can they all be translated into Latin phonetic spelling?” the 20th-century scholar and playwright Xia Yan (夏衍) asked rhetorically in his 2006 memoir. In the 1930s, scholar Zhao Yuanren (赵元任) even wrote a short story using characters with the same sound (but different tones), to demonstrate that the rich meaning of each character in classical Chinese couldn’t be replaced entirely by a phonetic system.

When the People’s Republic of China was founded in 1949, the illiteracy rate stood at 80 percent and the debate over abolishing Chinese characters persisted. However, the new government eventually compromised by keeping characters (but simplifying them) and introducing the pinyin romanization system in the 1950s. “The Chinese Pinyin Scheme is designed to provide phonetic annotation for Chinese characters and to promote Mandarin. It is not an alphabetic script intended to replace Chinese characters,” China’s Premier Zhou Enlai stated in 1958.

The approach proved effective. China’s illiteracy rate fell to 52 percent by 1964. Rates in Hong Kong and Taiwan, which maintained traditional characters, also fell, proving that the complexity of Chinese characters is no barrier to high literacy rates. By 2021, China’s illiteracy rate was under 3 percent.

Calls to abolish Chinese characters persisted until the 1980s. As the economy has developed, poverty and illiteracy have fallen, and respect for traditional culture returned, few now feel the need to eradicate the ancient script or adopt Western cultural tropes wholesale.

Lu Xun would surely be relieved to know that the tuberculosis he thought addled society was just a misdiagnosis in an uncertain time.