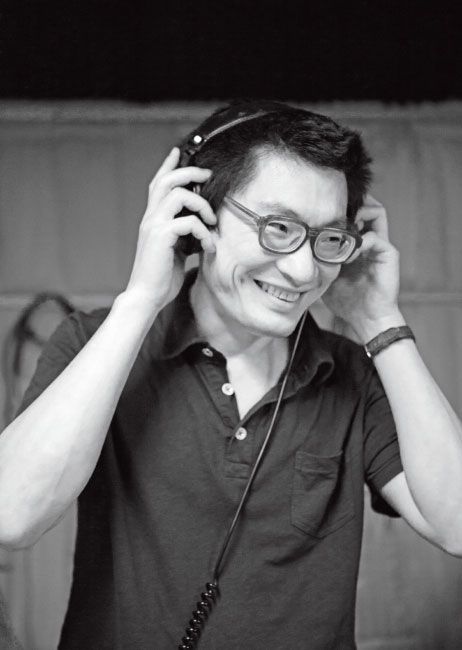

An interview with P.K.14 frontman Yang Haisong: the underground’s most important singer, mentor, poet and producer

There are two sides to Yang Haisong (杨海崧), frontman of the legendary indie-postpunk outfit P.K.14. First is the side people see onstage—the kicking, howling rock poet, a lanky, funky, fluid Ian Curtis who convulses across the stage like some epileptic visionary. This is the Yang Haisong who, since starting his band in Nanjing at the tail end of the ’90s rock explosion, has arguably become one of the most important musical figures in the Chinese underground.

And then there is the Yang Haisong who came to meet us outside his studio on the fringes of Beijing on an early summer’s day—a soft-spoken, quietly intense figure who somehow manages to look simultaneously like a cross between a professor and a guileless 10-year-old boy. Hair slightly rumpled, smoking a cigarette, he greeted us with a smile outside the Suning electronics store that sprawls above his underground studio, before leading us down through the parking garage to the bowels of his damp, chilly lair.

In addition to singing for P.K.14 and taking on occasional writing projects, Yang also works as a producer and engineer. Since starting his second career in 2007, he has recorded some of the underground’s most exciting young bands, including Carsick Cars, 8 Eye Spy and Birdstriking, making him one of the rare artists among his generation to have become an active mentor and supporter for new musical upstarts.

When we met, he was recording Alpine Decline, a husband-wife duo from Los Angeles who recently moved to Beijing. We stopped outside the door to Yang’s studio, pausing in the grungy, fluorescent-lit hallway to stare for a moment at the wall, which was covered in footprints.

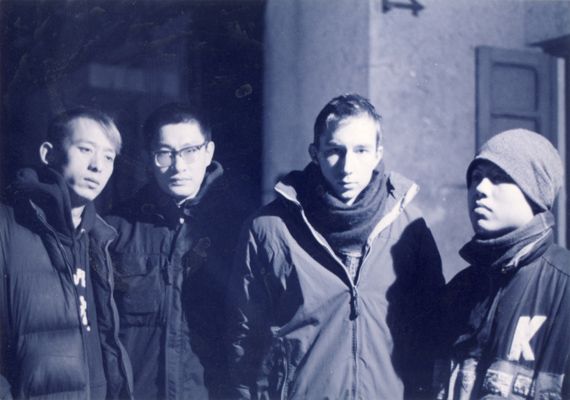

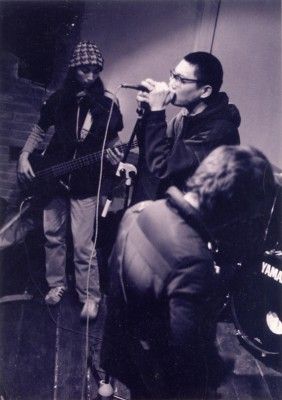

Yang Haisong (second from left) with P.K. 14 in 2003.

“Every day at four we have the wall-kicking contest,” said singer Jonathan Zeitlin. He took a sip of baijiu and directed us to a point about 10 feet up the wall, where a giant footprint presided at least two feet above the next highest contender. “That’s Haisong’s best kick.” We stared at the footprint in awe.

“How’d you kick that high?” we asked. Yang laughed and turned away.

“I don’t know, really,” he said, shrugging. This is classic Yang Haisong—he seems all normal, and then before you know it he’s landing footprints 10 feet up a wall… or, you know, becoming the most influential musician of his generation.

Between listening sessions in the studio, I sat down with Yang to discuss his childhood, his 15-year career in rock, and how he started his career in producing and mentoring up-and-coming bands.

What kind of kid were you? I imagine you as being kind of quiet and studious.

[Laughs] No, I wasn’t quiet. I was much noisier then than now. I wasn’t the best student, just a normal one. Not even really with literature. Nothing really special ever happened to me… Though I will say, as a child my grandmother was very influential. She was a high school teacher in Shanghai, and used to be a lawyer before liberation, so after New China, she got a lot of pressure. She raised two daughters, my mom and her sister. She had a lot of feminist ideas. She was an early, early Chinese feminist. Of course she would never say she was a feminist, she would just say this is how to be a person, to be a man or woman, and she talked a lot about this kind of stuff to me, as well as books and literature.

Did you have any ambitions to be an artist when you were a child?

Oh no, no. I didn’t have any ideas about what I wanted to be when I grew up. I didn’t think about those kinds of things. For young people of my generation, I think it was quite normal to find a job in a factory or making garments… That’s what most of the jobs were, not in a company. So I don’t think there was any space for imagination, for jobs for young people to think about what they’re going to do when they grow up.

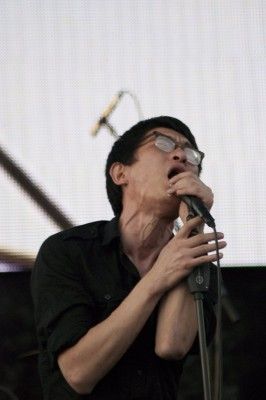

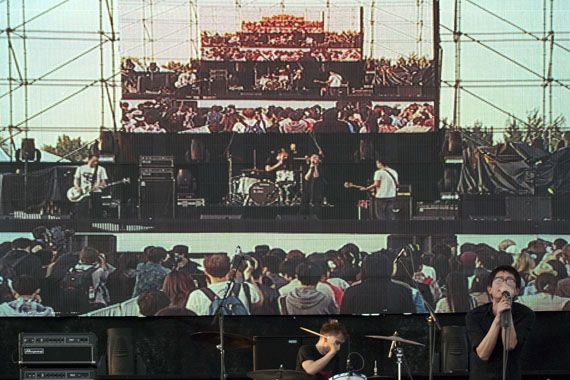

Yang Haisong at the Black Rabbit Music Festival in Bejiing, 2011.

So you thought you would just go work in a factory?

Yeah, actually that’s why I quit university. Because that was the only way to go after university. So I quit because I don’t like that kind of job.

How did your parents take it when you quit university?

They were angry, really angry about it. And between us there were a lot of arguments, a lot of discussion. It was a really hard time.

What were you planning to do? Had you already started playing in a band?

At my first university I was studying engineering and mechanics, and I really hated that, so I was trying to learn something more about literature or writing or something. But it wasn’t very normal at that time to transfer schools. So I tried to teach myself about writing and poetry, stories and literature… Then, almost at the same time, I fell in love with rock music. So for me, there were only two ways to go: be a musician or be a writer. And I wanted to be a musician.

You first heard rock music in 1993 on the radio. What was it that most appealed to you about it?

I think the music hit me at just the right time. People in their 20s or teens were very nervous about the future. From teenagers to almost middle-aged people, we felt a bit as though life was passing us by. And then rock music like Tang Dynasty or Cui Jian showed us a different way to go—that you could live another kind of life. I think it had a huge impact on young people; it was completely revolutionary.

And has the artist’s life been similar to what you imagined?

No, it’s been totally different! At that time, all of my images of the life of an artist were very poor; it was like Tang Dynasty and Cui Jian. We heard about it on the radio and through some stories of the Beijing rock scene, that they were all very poor with ramshackle houses, and they had long, dirty hair, but they had a very strong spirit and were very focused on what they were doing. So that was what I imagined about the life of an artist. I told myself, if you want to be a musician, it’s going to be something like that. You’ll never have any money, you’ll have to ride your bicycle everywhere and nobody’s going to love the music; there will never be any audience. They would just love pop music, and yours isn’t so sweet. And I thought, yeah I can do that. But now it’s totally different. A lot of things have changed, and you can play a lot of shows, you can get some money from that and from touring, from brands, like Converse—it’s not what I imagined 15 or 20 years ago.

At that time, there wasn’t much of an audience, right?

Actually, I can’t say there’s a bigger audience now than before. I think it’s almost the same. I mean, the real audience who comes to the show. The first time I saw Tang Dynasty in Nanjing in 1993, it was in a big stadium, and there were almost 10,000 people there, and they all looked really excited. Now it’s really hard to imagine an underground band playing in a stadium to 10,000 people who are all excited about it.

So how did you make the leap from listening to rock music to starting your own band?

It took me four years to join a band, which happened in 1997, when I started P.K.14. I had played in other bands before, like 西, but P.K.14 was my first serious band. I’d tried to be a folk singer like Bob Dylan or Neil Young, playing my guitar and just doing solo stuff. I played some shows, but the projects were all very immature. I even played drums for a Metallica cover band! But I think those four years really let me learn how to play in a band and to work with other people as partners. It was kind of just like preparation for P.K.14. But I didn’t know that at the time, so I felt very upset, very nervous, always going, “I want to be, I want to play, I want to something something.”

You have a really unique vocal style. How did that develop?

Actually, I don’t know. I never seriously think about my singing or my singing style. I used to sing kind of like Bob Dylan, you know, like an old man. And also I really liked some punk music, like the Sex Pistols, The Clash and some New York bands like Television and Richard Hell. So when I started to sing in P.K.14, I guess it was just natural to try and sing like Tom Verlaine from Television, or Richard Hell. It’s quite different—it’s not shouting or screaming… it’s like talking, but with a little bit of a nasty feeling.

Did it feel natural, or did it feel like you were imitating?

It felt a little bit unnatural at the beginning, but I think it’s because Chinese and English lyrics are quite different, the pronunciation is quite different. So I had to try to figure out a natural way to sing Chinese lyrics. When I sang the songs, I had to focus on all the characters, how to pronounce this word. I think it was a good way for me to focus on all the lyrics, to sing with a focus on how the lips and tongue work to push the words out, with more punch. And later on, it became natural.

You have an incredibly powerful stage presence. Did that come about naturally?

Actually, it wasn’t very natural for me—it still isn’t. In the early days of P.K.14, all of us were quite quiet and we didn’t move very much. So I’d just be standing and singing. But I guess it was because of all the touring we did… we played so many shows and were so tired that it was really hard to keep standing in front of the microphone playing the same songs. It’s boring, actually, on tours when you’re doing it night after night. So I started trying to move, and the guitar player started trying to move. We were just like, “Let’s do anything, let’s go crazy.”

P.K. 14 performing in 2000.

When did that start?

It started on our 2004 tour of China. Before that tour, our bass player was Sun Xia [Yang’s wife], and she’s very quiet and would even turn her back to the audience. So it was kind of like nobody wanted to move because she wasn’t moving. And after that Shi Xudong [the band’s new bassist] came, and he’s so crazy, so he gave us a lot of energy to do something onstage.

Your wife Sun Xia was the original bassist for P.K.14, and these days you make music together as Dear Eloise. How do you think she’s influenced your music over the years?

As a person I have two sides, and she’s my darker side. One side of me is more punk, more energy, more rock, and she is darker, colder, more beautiful. So if I hadn’t met her, my music would be different in a way. I think I’d be an angry young man [laughs]. I would say she is like a window into another world… one totally different from the one I know. She came from the countryside, and she moved to Beijing quite young. She’s lived a totally different life from me, so I’ve learned a lot from her.

You’re a writer as well as a musician. How is writing poetry different from writing lyrics?

It’s a little bit similar, actually. A lot of my lyrics come from my poetry; I rewrite it and fix it into lyrics. But for me, poetry is more free. In several lines you can change your tempo and break the rhythm, but lyrics you have to shape quite rigidly for the music. But with poetry in general there are no limitations, so you can write whatever you want. You start from one point and you open up line by line, so when you finish, the original point has disappeared, but the poetry that’s left is beautiful. With lyrics you have to go back to focus on the point. You start from a single point, and you expand from it with stories and rhymes, but after all that you have to go back to the point. This point is the most important thing, the reason that you started to sing this song.

Where do you look for inspiration for your writing?

A lot of things inspire me to write—events happening in society, something online, something that happened in Shanghai or Yunnan or some small town, or some political issue or some sensitive thing, who knows? Or even just my neighborhood, or someone I saw on the street, some stranger, some face, or even just a picture in a magazine.

Who are some of the artists who have had the biggest influence on you creatively?

I think most of them are writers; actually a lot of American writers, like Hemingway, J.D. Salinger, Jack Kerouac, Raymond Carver, Fitzgerald. Also, T.S. Eliot. But for music, it’s like Bob Dylan of course, Woody Guthrie, The Clash, Joy Division, Television, Fugazi, Sonic Youth—it’s quite a long list.

What are some of the biggest differences you see between the older bands from when you started out and the newer bands in terms of how they approach music?

When we were young and started thinking about becoming rock musicians, we knew that our lives would completely change. When you did that, you were crossing a line, going to the other side… But now I think if you want to be a musician and be in a rock band, it’s ok—you’re still living in this world, you don’t need to go to another side and be rebellious or dangerous or considered a bad guy on the street. Your parents won’t necessarily think you’re doing really bad or a loser.

Did your parents act that way when you started playing music?

Yeah, of course, and all my friends’ parents too, thought we were just lazy, bad losers.

And now what do your parents think about your career in music?

They think I’m not as big of a loser, but they still don’t really understand. They can accept it, but of course they don’t want me to live this kind of life.

Is there anything that you miss about the ’90s, when rock music was more outside of the mainstream?

No [laughs]. There were some good things about it, because you felt like it was you against the world. Our parents and teachers saw us as losers, or as rotten. So we just said, “Ok, we’re rotten. We want to do nothing, we just do what we want.” And maybe that was good for a while, but I don’t miss it, because I already spent that time—that was my life.

You guys are one of the few big bands who don’t usually play festivals. Why is that?

It’s partly because the sound isn’t very good, but it’s also because the organizers aren’t that great; they’re all a bit of a mess.

Do you think festivals as they’ve been organized in the past few years are ultimately a good thing for rock music here?

I wouldn’t say it’s good or bad. It’s something that should happen, I guess. For example, we can compare with American rock—after Elvis Presley, it was almost the same. Rock became something commercial, and after the hippies and San Francisco sound, in the ’70s all the rock music was going commercial. But I mean people always say that rock is dead. And in China you can say that, but there’s going to be a revival; it’s a circle. I won’t say it’s good or bad about the festivals or promoters. I’ll just say that we don’t really like that way of playing music. Maybe all the bands like that because they can play on a bigger stage, but it’s not our way.

You started working as a producer in 2007, when Carsick Cars asked you to produce their first album. What is something that you know now about producing that you wish you had known earlier?

I wish I’d just had a lot more of the skills—knowledge about the computer, the software, the hardware, the equipment. But to me, producing is more about communication with the musicians, so because I’m a musician it’s easier for me to know what they want to do. Because all musicians have their ideas about the music, they’ve all imagined how they want it to sound, but they don’t have the skills or knowledge to put that down in the recording. But I know some of that, I have some skills, and I can help them that way.

Yang Haisong takes feedback from Alpine Decline's Jonathan Zeitlin in studio in 2012.

What is your favorite recording that you’ve done?

I think my favorite is 8 Eye Spy, I love that recording. And actually that was my first time working as both engineer and producer, the first time I had controlled the mix table by myself. It wasn’t like with Carsick Cars or Ourself Beside Me, where I had another engineer to support me. But I discovered that communication among so many people is really hard. I like doing engineering myself, so I can talk to the band directly and then work on the recording, so there’s nothing between you and the band.

Do you have any favorite young bands?

There are a lot; obviously, I like Carsick Cars… but I guess they’re not so young anymore. Actually, this year I really focused on Skip Skip Ben Ben, and I think I’m going to record them. They’re really good. Also Chui Wan, and some other bands from Zooming Night, though I can’t say whether they’re all serious bands or just a project. Also Deadly Cradle Death, as well as Luxinpei and Fat City.