As well as costing her an architecture degree, Lin Huiyin’s gender would lead many to focus on her looks and alleged love affairs over her groundbreaking work

On May 18, 2024, the University of Pennsylvania awarded Lin Huiyin (林徽因) with an architecture degree, exactly 100 years after they refused to admit her into their undergraduate program because she was a woman.

Dubbed the “first and most famous female architect in modern China” by the university, Lin is renowned in her home country but barely registers abroad. “When you come to America, everyone knows of Frank Lloyd Wright. When you go to China, everyone knows of Lin and [her husband] Liang [Sicheng],” said Genie Birch, a professor at Lin’s alma mater, now known as the Stuart Weitzman School of Design at the University of Pennsylvania, after Lin was honored. But compared to her decorated husband, Lin’s professional achievements often receive less attention than popular narratives about her personal life, including praises of her beauty and style, and rumors of various love affairs.

With the news of Lin’s belated degree quickly going viral on Chinese social media, her name is again in the public eye. It is therefore a good opportunity to revisit her legacy and correct the prejudice and stereotypes that have overshadowed Lin’s story.

A pioneering student

It is a common misconception that Lin’s interest in architecture began due to her influential husband, Liang Sicheng (梁思成), often feted as the father of modern Chinese architecture. However, plenty of evidence suggests that Lin had indeed dreamed of becoming an architect from a young age, and was aided by her unwavering drive and talent.

In 1904, Lin was born into an intellectual family in the southern Chinese city of Hangzhou. Her father was a politician and diplomat, a standing that granted Lin and her two younger brothers excellent educations. Lin attended elementary school in Shanghai and then a British missionary-run middle school in Beijing. At 16, she traveled to Europe with her father, continuing her education there.

In Europe, Lin gradually developed an interest in architecture and resolved to seek higher education in the subject. In 1924, Lin journeyed to the US to attend the University of Pennsylvania with several other Chinese students, including her future husband Liang Sicheng, the son of well-known Chinese political reformer Liang Qichao (梁启超).

Liang enrolled in the university’s architecture program, but Lin was not admitted as, before 1934, the architecture school at the University of Pennsylvania was not open to female students. Justifications for this segregation included the belief that it was considered improper for young ladies to work late into the night, unsupervised, especially with young men. But Lin did not give up without a fight. She repeatedly sent letters to the school through the Chinese Embassy in the US, requesting to be admitted. However, they did not concede, and finally, Lin enrolled in the Bachelor of Fine Arts program.

Read more about badass Chinese ladies:

- Zhang Weili and China’s Upcoming Fight of the Century

- Tang Qunying: One of China’s Earliest Feminists

- Mathematician and Astronomer Wang Zhenyi

Despite this setback, Lin did not give up her dream, and over the following three years completed the majority of courses required for a Bachelor of Architecture degree—among the exceptions was a life drawing class that was not open to female students because the models included men. Lin’s academic record contains many “D” grades—for distinction—outperforming many of her male peers. In 1925, she would even become a teaching assistant in architectural design.

Just a few years later, the School of Fine Arts began awarding degrees in architecture to women who graduated before 1934. However, for reasons that remain unclear, Lin went unacknowledged and would not be awarded until nearly a century later.

A forerunner in China’s architecture

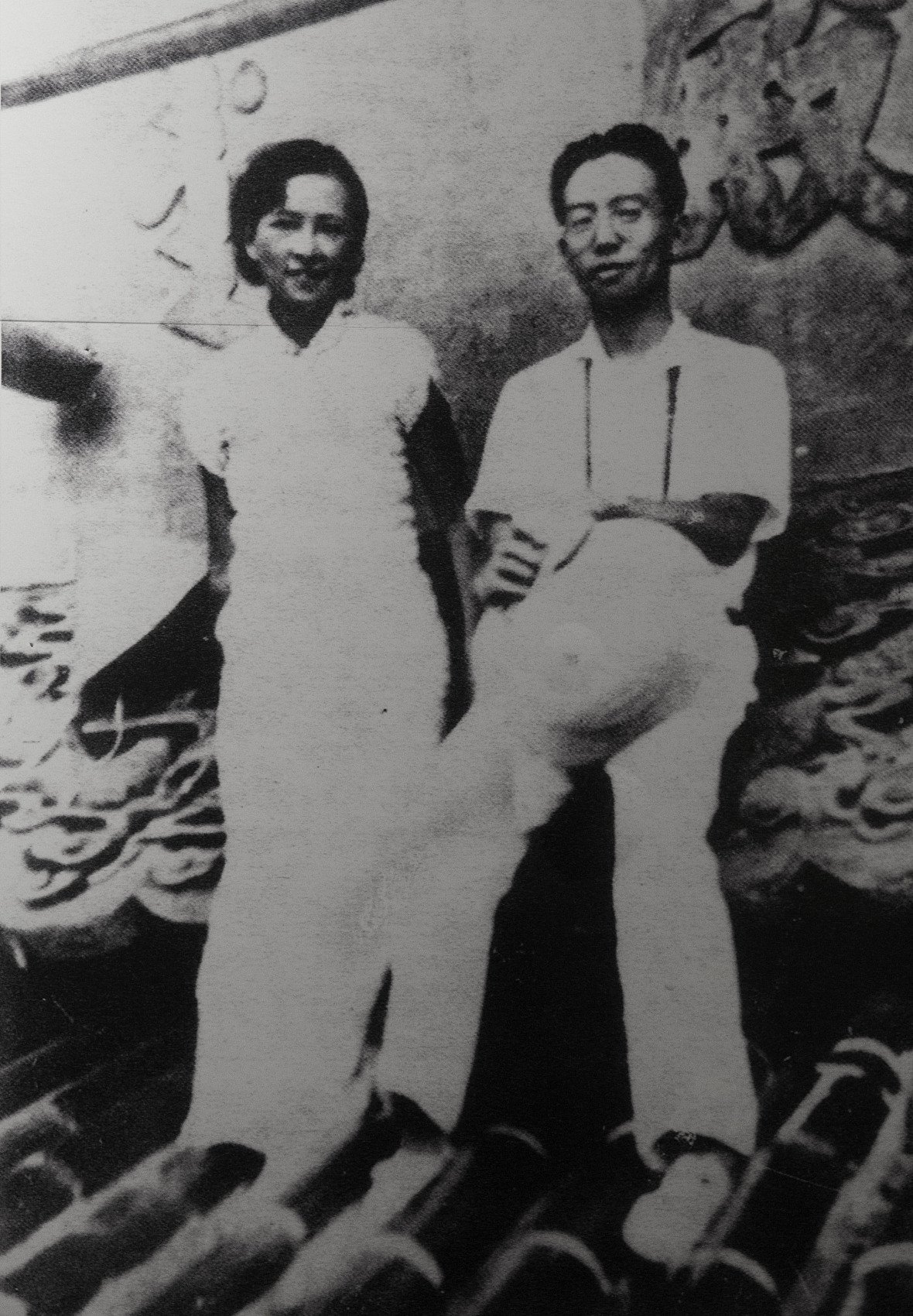

In March 1928, Lin and Liang were married in Canada. In July, China’s Northeastern University in Liaoning province established its architecture department and invited Liang to serve as a professor, seeing the newly married return. In 1929, Lin also became a full-time professor in the university’s architecture department. At the invitation of Liang and Lin, some of their former classmates from Pennsylvania, including Chen Zhi (陈植), Tong Jun (童寯), and Cai Fangyin (蔡方荫), also came to teach at the university. Within just one year, a prestigious architecture program, the second-ever in China, was established, with over 20 students and a comprehensive range of courses.

However, not long after, Lin contracted pneumonia and traveled to Beijing for treatment. In 1931, Liang accepted a position with the Society for Research in Chinese Architecture, a civil organization specializing in the research and preservation of traditional Chinese architecture, and went to join Lin in Beijing.

During her time in Beijing, Lin, who had since given birth, had to juggle her work with her domestic obligations. In 1932, in a letter to her friend Hu Shi (胡适), Lin expressed her struggle between ideals and reality: “I have reached a considerable age without much achievement, and it seems that opportunities are becoming fewer...I’m really afraid of living an ordinary life, just being a wife and having children for a lifetime!”

Fortunately, the pressure of being a wife and mother did not hinder Lin’s passion. In the 1930s, Lin and Liang traveled around the country to survey and record remnants of ancient Chinese architecture. Between 1930 and 1945, they conducted research on 2,738 ancient architectural sites across 190 counties in China.

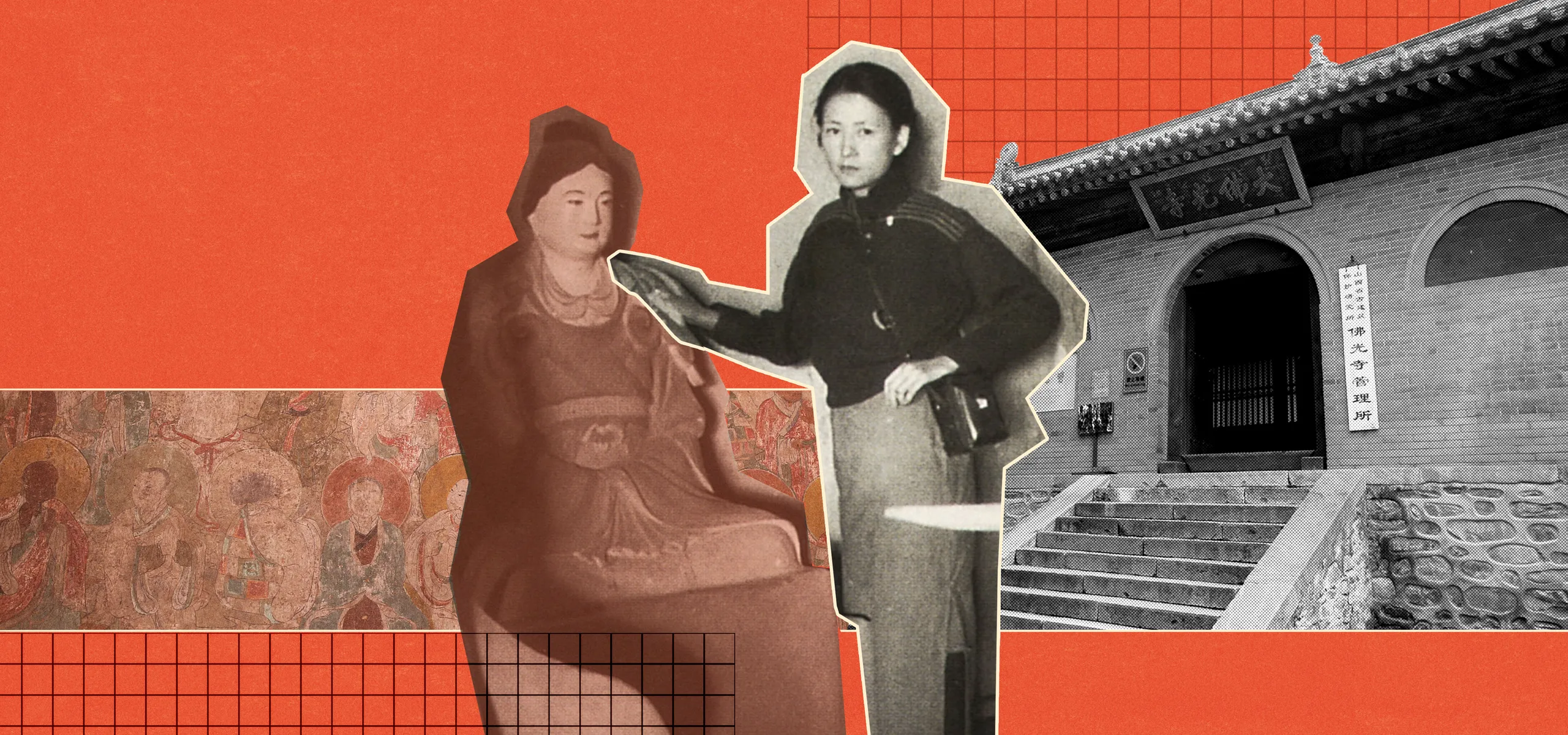

Their most important discovery occurred in 1937. During an expedition in Shanxi province in central China, Lin and Liang found an obscure wooden temple in Wutai county. At first glance, the complex didn’t appear particularly special, but it was soon hailed by Liang as a national treasure. Built in 857, the Foguang Temple was the oldest wooden architecture found in China at the time. It also housed many sculptures, murals, and calligraphic inscriptions from the Tang dynasty (618 – 907)—an era from which, until then, few architectural treasures were believed to have survived.

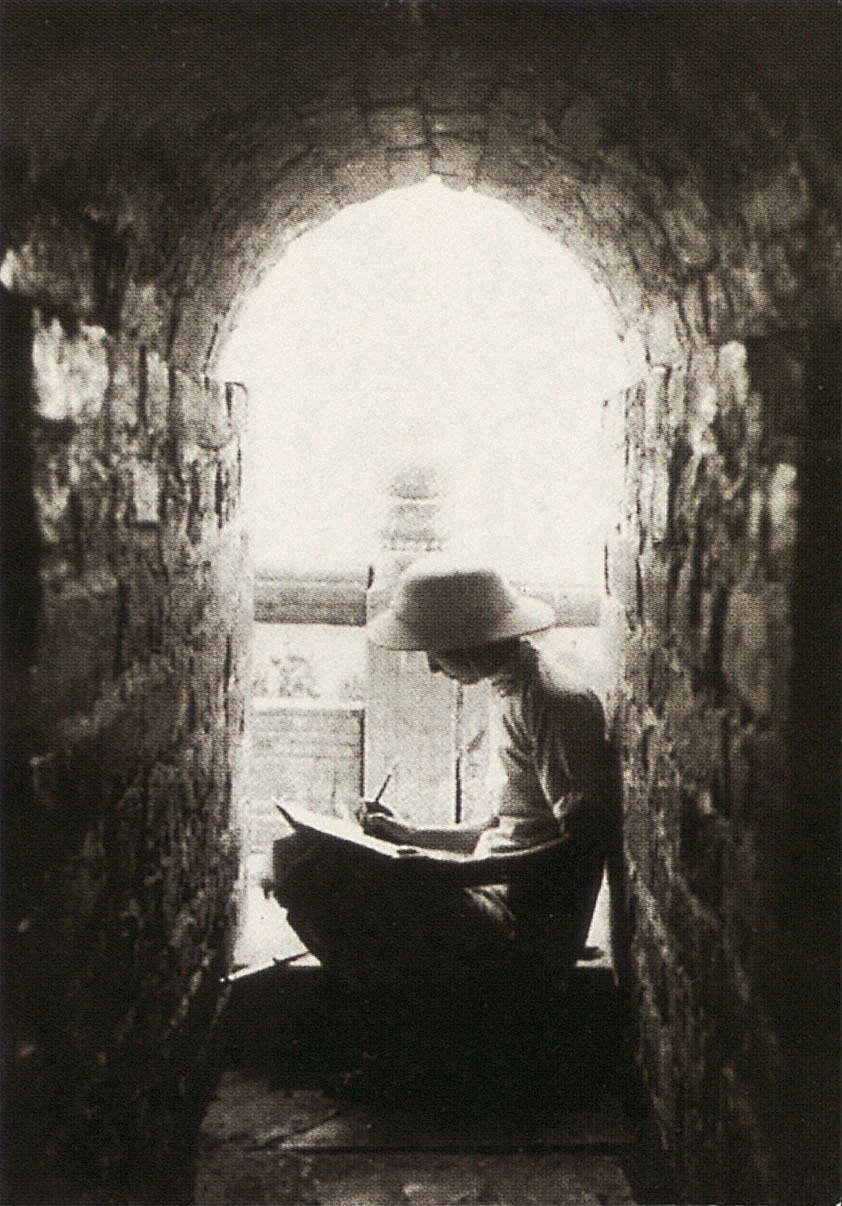

Lin was elated at the discovery. Liang Congjie (梁从诫), the couple’s son, recalled in his article “Reminiscing My Mother Lin Huiyin” in 1987: “Many years later, my mother would often tell us about their excitement at that time. She told us how they climbed up to the ceiling of the grand hall and took measurements amid the millennial dust stirred by countless bats and the ubiquitous bedbugs. She, with her far-sighted eyes, suddenly noticed a faint line of characters beneath the main beam. It was these characters that became the definitive evidence of the building’s age.”

Their explorations ended when Japan invaded China in 1937. In 1938, Lin and Liang Sicheng moved to Kunming in the remote southwest of China to avoid the chaos of war. In 1940, they moved again to a small village in neighboring Sichuan province due to the increasingly severe air raids by the Japanese invaders on Kunming.

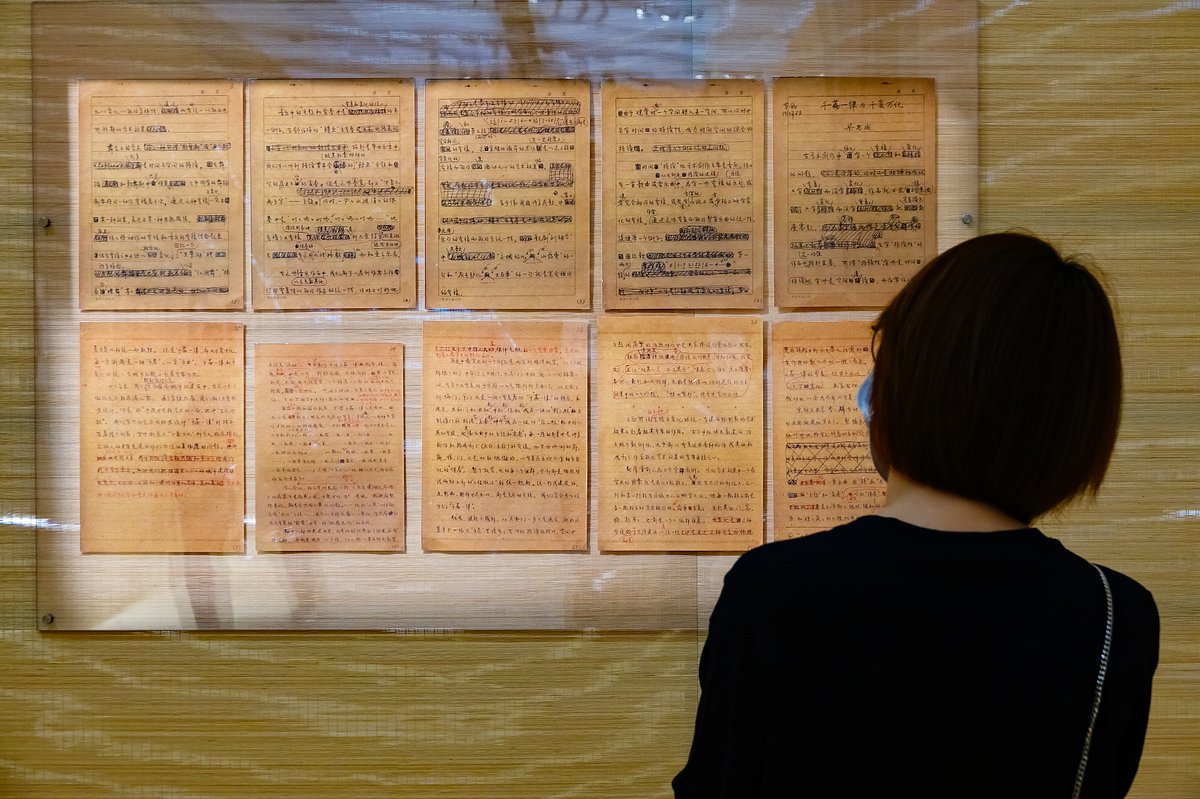

Despite Lin’s chronic tuberculosis worsening during this period, she and Liang Sicheng would compile their years of research in the cottage they built together. The result was the book A History of Chinese Architecture, which they published in 1944. In it, they summarized the architectural achievements and chief characteristics of buildings throughout various stages of Chinese history, marking the first major book on Chinese architectural history written by Chinese authors. Lin finished the chapters about architecture in Song (960 – 1279), Liao (907 – 1125), and Jin (1115 – 1234) dynasties, and proofread the whole text. The couple also wrote an English book called A Pictorial History of Chinese Architecture, which was published in 1984 in the US and later translated into Chinese by their son.

Lin continued her work after the PRC’s founding in 1949, though her health was failing fast—in 1947, tuberculosis infected one of her kidneys, forcing her to have it removed. Nevertheless, Lin was successively appointed as a professor in the School of Architecture at Tsinghua University, an engineer of the Beijing City Planning Commission, and a delegate to the first People’s Congress of Beijing. In the six years before her death in 1955, she participated in the design of the national emblem and the Monument to the People’s Heroes, campaigned for the protection of ancient buildings in Beijing, and enthusiastically advocated for the revival of traditional crafts, such as cloisonné enamel.

“My mother had a strong sense of liberation,” Liang Congjie recalled in his article. “In the old times, although she had taught at universities, published articles, and was quite famous, she was always the wife of Liang Sicheng without an independent social identity...[Now] it was truly as Lin Huiyin that she took on social duties and served the people.”

A misunderstood poet

Besides her work in architecture, Lin is also renowned for her poetry. She wrote over 60 poems in her lifetime, in addition to novels, essays, and plays.

The popular story goes that Lin’s inspiration to write—much like her interest in architecture—came from her relationship with another man: the poet Xu Zhimo (徐志摩). Lin met Xu, a friend of her father’s, while she was studying in London. Xu was seven years older than Lin, and married, but still launched a passionate pursuit. However, Lin did not reciprocate his feelings. According to Liang Congjie, Lin reflected, “Xu Zhimo didn’t love the real me at that time; instead, he fell for an idealized Lin Huiyin imagined through his poetic romantic sentiments.”

In 1923, Xu and several other poets established the Crescent Moon Poem Society in Beijing. Lin became a member, though she would not publish her poetry until many years later. In 1924, when the Indian poet Tagore visited China, Lin was among the members of the Crescent Moon Society who received him.

Lin’s earliest published poems, “That Night” and “Who Loves This Ceaseless Change,” appeared in Poetry, a magazine founded by Xu, in 1931. That same year, Xu died in a plane crash, and Lin would write “In Memory of Zhimo” to express her grief at the time.

Liang Congjie noted in his “Reminiscences” that from two poems Xu wrote to his mother, “one can perceive the thread of their relations, which is indeed much nobler than the general rumors outside.” However, Lin’s acquaintance with Xu has since dominated the narrative of her life, and been inflated with much unfounded hearsay.

In 1993, writer Lin Shan published the biographical work The Genius Woman Lin Huiyin, winning the inaugural China Excellent Biographical Literature Award the following year. However, when the book was published in Taiwan the same year, it included an additional subtitle: “From Xu Zhimo’s Soulmate to Liang Qichao’s Designated Daughter-in-Law”—effectively reducing Lin’s identity to her relations with the two famous men in her life.

Lin’s most renowned poem, “You Are the April of This World,” was written in 1934 for her son Liang Congjie after his birth. But in 2000, a popular TV drama titled April Rhapsody was aired, focusing on Xu Zhimo’s emotional entanglements with various women, including Lin. The title of the show caused many viewers to mistake Lin’s poem as a declaration of love to Xu, and the show’s portrayal gave Lin a reputation as a woman who was fickle in matters of love.

In a 2023 paper published in Modern Science journal, researcher Meng Zhaoyuan analyzed the coverage of Lin in the Shen Bao, Dagong Bao, and People’s Daily newspapers over the past 100 years. Meng found that the two former, commercial publications focused on showcasing Lin’s literary talent, often portraying her as “brilliant literati,” while the Party-run People’s Daily tended to promote her as an “activist for the nation and its people.” The identity of Lin as an architectural scholar was overlooked by all, and gradually decreased in newspaper reporting over time. “The public’s perception of Lin Huiyin is heavily influenced by the media’s portrayal, which ignored her identity as an architect,” Meng wrote.

Lin died of tuberculosis in 1955 and is buried in Beijing’s Babaoshan Revolutionary Cemetery alongside many other important figures in modern Chinese history. Her tombstone, bearing only six Chinese characters, provides her the recognition she deserved all along: “Architect Lin Huiyin.”