Yeung Sau-king was the first female athlete to represent China at the 1936 Olympics (and also a journalist and spy), but not even medals could protect her from tabloid rumors and misogyny

When Siobhan Haughey punched the wall at 52.33 seconds in the 100-meter freestyle race at this summer’s Paris Olympics, it was enough to earn the Hong Kong swimmer a place on the medal stand. While Haughey is celebrated as the only Hong Kong swimmer in history to earn an Olympic medal, she is also upholding a legacy that stretches back nearly 100 years to a young woman known to the public by her nickname, the Chinese Mermaid.

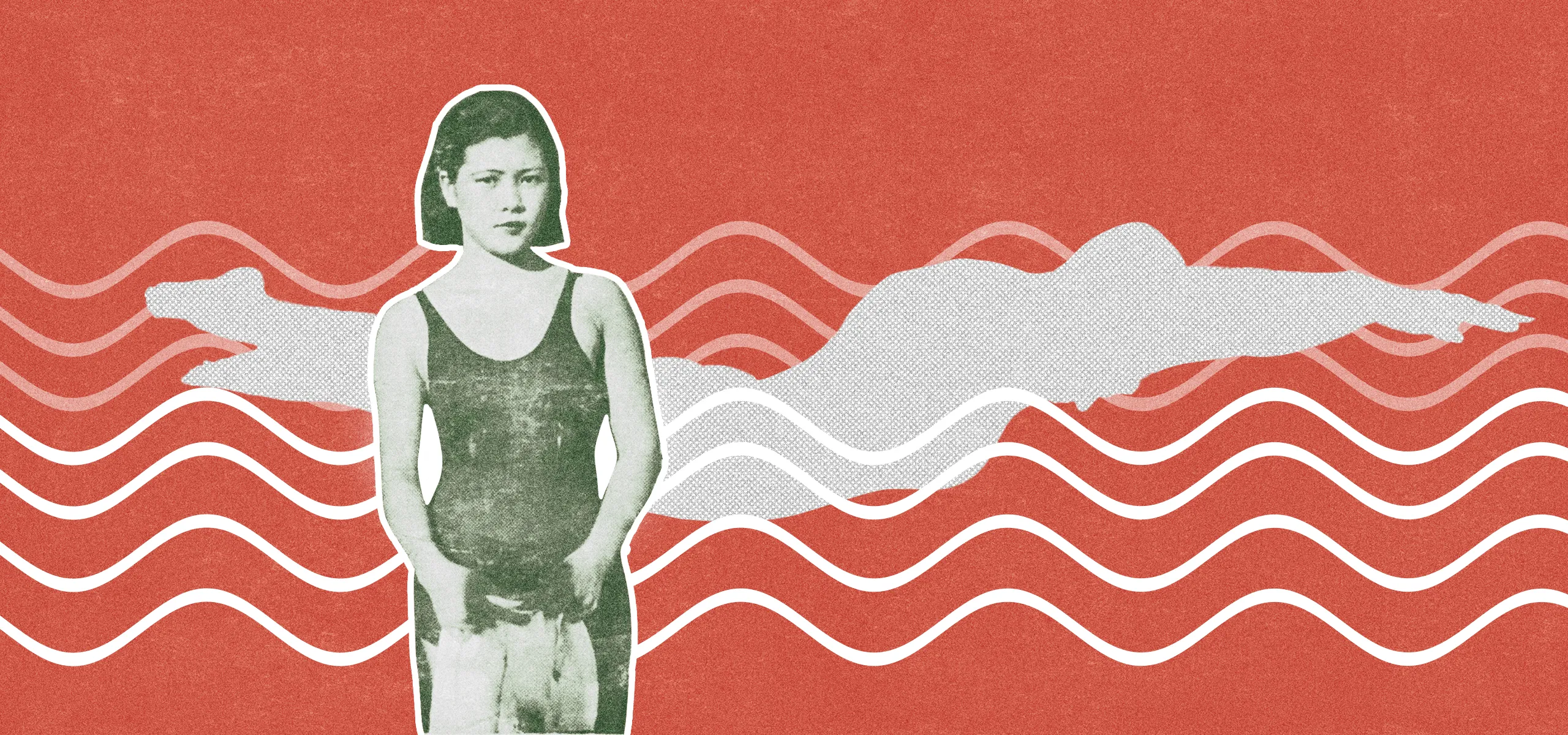

The Mermaid was Yeung Sau-king (杨秀琼), also known as Yang Xiuqiong or Yvonne Yeung, who rose to fame as a teen and then carried the complicated burden of stardom throughout her life. As China’s first female Olympian, Yeung lived through the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong, where she worked as an underground agent for the resistance, only to see her name dragged through the mud of tabloid headlines in a manner strikingly similar to many Olympic stars—and even ordinary women in sports—today.

Yeung was born in 1919 in Dongguan, Guangdong province, and moved with her family to Hong Kong, then under British rule, at the age of 10. Her father was a swimming coach who taught her and her two siblings to swim as children. In 1930, Yeung broke the women’s record in Hong Kong’s Cross Harbor Race, an annual competition that not only was the most popular swimming event in the British colony, but also one that allowed Chinese as well as female participants. Yeung, only 12 years old, completed the swim from Tsim Sha Shui to the Queen’s Pier on Hong Kong Island in 32 minutes and 39 seconds.

Yeung soon began to represent Hong Kong at national sports competitions, which proliferated at the time in China. In 1933, at the Fifth Chinese National Games held in Nanjing, she won gold medals in all five swimming events. The following year, in the Far Eastern Championship Games in Manila, she won four more. The historian Xu Guoqi has written that competitive sports were a key political platform in the 1930s for the Kuomintang (KMT), then the ruling party of the Republic of China. Along with the passage of a national law in 1929 emphasizing the importance of physical education, the phrase tiyu jiuguo (体育救国), meaning “using sports to save the nation,” became a part of the national lexicon.

Read more about badass Chinese ladies:

- Reclaiming the Genius of China’s First Female Architect

- Badass Ladies of Chinese History: Mathematician and Astronomer Wang Zhenyi

- Tang Qunying: One of China’s Earliest Feminists

- Qin Liangyu: Ancient China’s Unstoppable Female General

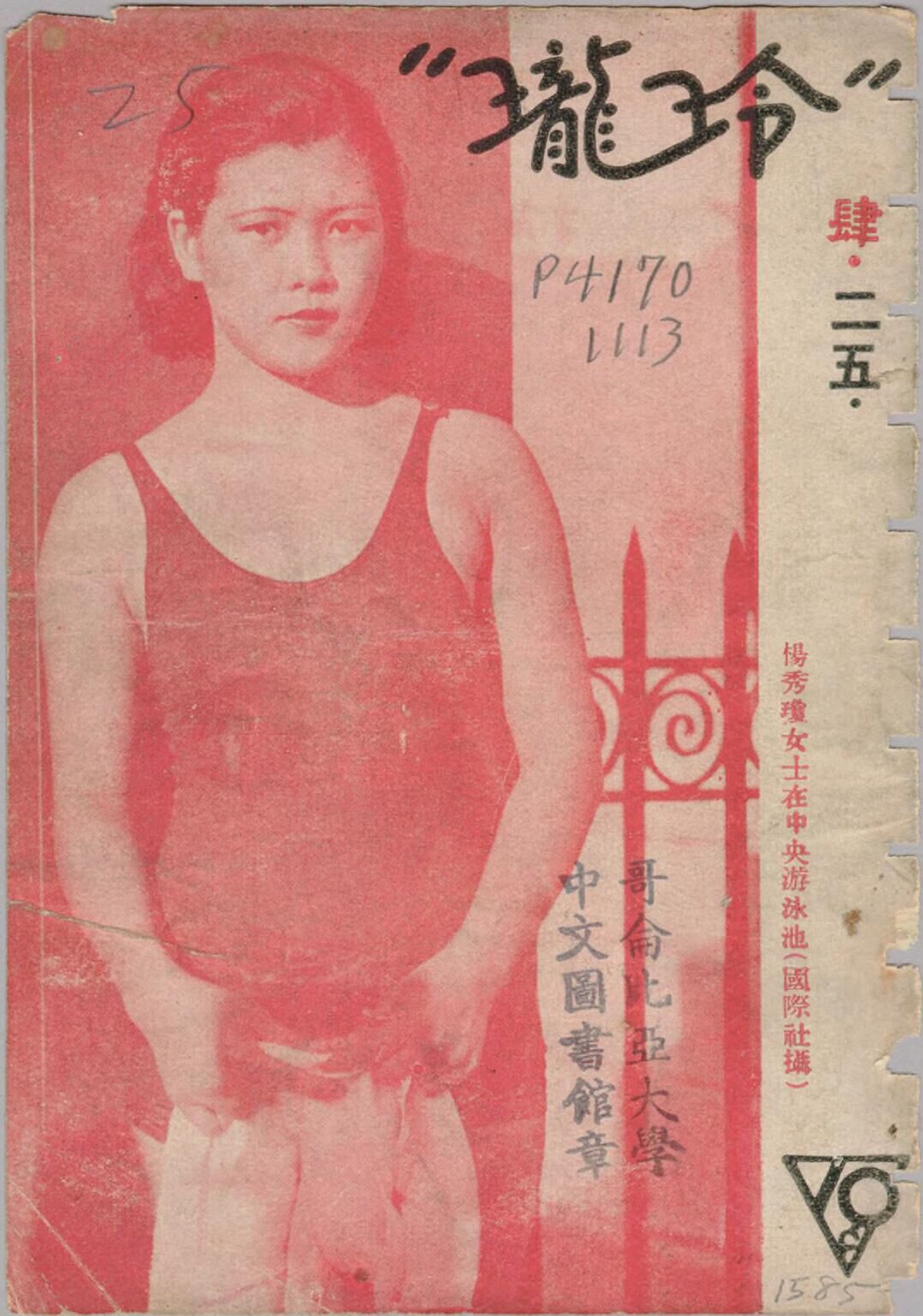

These record-breaking results made Yeung a star, not just as an athlete but as a role model for women. Following her initial success in the National Games, she was given the “Chinese Mermaid” nickname by a Shanghai newspaper. News and photos of her circulated among Chinese periodicals, including many lifestyle magazines in Shanghai. Most notable was the popular pictorial The Young Companion, which featured a swimsuit-clad Yeung on its cover in 1933, and in 1934 listed her as one of ten “model women” in China, alongside the painter He Xiangning (何香凝) and the writer Ding Ling (丁玲).

That same year, the KMT also invited her to promote the “New Life Movement,” a campaign that aimed to encourage cultural reform toward a Neo-Confucian ideology. She participated in the opening of government-run swimming pools in Nanchang, Jiangxi province, and gave a swimming performance in the capital city of Nanjing. Both events drew large crowds.

But the headlines were not all praise. Some criticized Yeung’s revealing outfits while others accused her of seeking attention, painting her, in the words of Linglong magazine, as “a vase on the sports field” instead of a hard-working athlete. And when Yeung achieved only a silver medal at the beginning of the 1935 Chinese National Games in Shanghai, newspapers blamed her result on the 16-year-old’s “epicurean lifestyle,” according to Pun Wai Lin, a journalist and the author of a recent biography on Yeung.

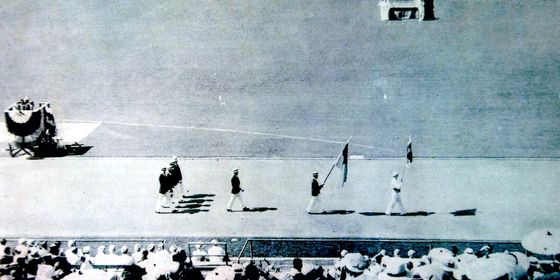

Yeung reached the peak of her athletic fame in 1936, as a member of the team representing the Republic of China at the Berlin Olympic Games. While sprinter Liu Changchun had been the only Chinese athlete competing in the previous Olympics in Los Angeles, China sent 69 athletes to Berlin, including many from Hong Kong. The Berlin Games were controversial, as Germany was three years into Nazi rule, but the KMT saw an opportunity to highlight China’s growing sporting strength as well as tighten what was then a relationship with Berlin, who supplied large amounts of military aid and trainers to the government in Nanjing.

Yeung, however, could not achieve the same results on the global stage as she did back home, and failed to advance past the preliminary rounds. Just as newspapers had criticized her for coming in second at the National Games, they demeaned her performance in Berlin as “appalling,” in the words of the government-run Central Daily News. But as Pun writes in Yeung’s biography, the swimmer did not wallow in her defeat, and instead published an autobiography upon returning to Hong Kong, as well as articles for local newspapers about her Olympic experience.

Only one year after Yeung’s Olympic debut, her career as an international swimmer was interrupted by the full outbreak of war against Japan in 1937, one of the starting pistols of the wider world war that would soon engulf the planet until 1945. Understandably, athletic competitions were halted during this period, and no Olympics were held again until the 1948 London Games. As Hong Kong was spared Japanese occupation until 1941, Yeung was able to continue some sense of normal athletic life. She competed in the 1939 South China Athletic Association Swimming Championships, winning the 100-meter backstroke event in what would be her final race as a competitive swimmer.

In December 1941, the Japanese Empire attacked the US naval base at Pearl Harbor and occupied the British colonies of Hong Kong and Malaya. Yeung began serving as a special intelligence officer for the KMT. According to documents held by the Japanese National Archives, from 1942 to 1943, Yeung worked for the KMT’s Bureau of Investigations and Statistics, run by the notorious spy chief Dai Li (戴笠), where she was responsible for gathering information on the Hong Kong activities of the Japanese-supporting puppet government of China and other Japanese sympathizers. This underground network was discovered by the Japanese in 1943, and Yeung endured a period of Japanese interrogation. Following her release, Yeung moved from Hong Kong to Shanghai, where she remained following the Japanese defeat, working as a journalist for the newspaper Qiaosheng Bao.

Yeung’s life was marred by the chaos of the time period, but also by her excess of fame, especially in her personal life. In 1939, she married a famous Hong Kong jockey, Tao Bolin (陶柏林), in a celebrity marriage of the period. But Tao was an abusive husband, and soon abandoned Yeung and their two children. Though Yeung was no longer competing in races, she was still a household name, so speculations about her marriage and possible divorce were juicy fodder for the tabloids.

Similarly, rumors surrounded her and Fan Shaozeng (范绍增), a notable lieutenant-general during World War II who was said to have “taken her forcibly” as his 18th concubine. The biographer Pun asserts that this relationship with Fan never happened, and that the tabloid allegations were impossible when looking at reliable evidence.

In 1948, she married again, to a Chinese-Indonesian businessman. This time, it was a quieter affair than the headline-making splendor of her first wedding. After living in Thailand for a time, they moved back to Hong Kong. Yeung remained active in Hong Kong society, and was eventually awarded the Medal of Merit by the Commonwealth for her work at the Royal Life Saving Society, a British charity for drowning-prevention. She slowly faded out of the public eye.

The last we hear of Yeung is her gift shop, Creation Boutique. It sat quietly at 5641 Dunbar Street in Vancouver, Canada, where Yeung and her family had moved in the 1970s. Here, the former Olympian shared the worldly treasures she gathered over her lifetime with the rest of the community. In 1982, Yeung passed away in an accident, falling off a ladder at home.

Yeung’s legacy is complicated, like many athletes whose star rises at a young age. Though her athletic achievements made her a celebrity as a teenager, she also spent most of her life objectified as a beauty and status symbol. Her achievements were buried in tabloid headlines that tore her down as quickly as they built her up, while her work as an intelligence officer would not be known until years after her death, when national archives were declassified. For any athlete, it’s a reminder of the mercurial nature of fame on and off the field: just as big a challenge on social media today as in newspapers a century ago.