China’s liberal arts students still value their expertise in the face of poor employment prospects, low salaries, and societal pressure to switch to STEM subjects

Zheng Xinyue left the job fair disappointed. It was autumn, a traditional time for university students to seek employment after they graduate, and the 22-year-old cultural industry management major had been ignored by almost all the potential employers there.

In the weeks around last year’s fair, she had sent some 30 job applications but only received a handful of interview requests. As a liberal arts student from a lesser-known university (not part of China’s prestigious 985 or 211 groupings of schools), she felt unemployable. “Even though I have taken seven internships, and I am equipped with the necessary skills, HR departments from my ideal companies like Bytedance, Huawei, and Alibaba never give me an interview,” Zheng tells TWOC.

It might have been different if Zheng had studied a science subject. In today’s China, science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) graduates often have better employment opportunities and higher wages than their liberal arts peers in an economy that the government hopes will move up the industrial value chain. China’s leaders often talk about semiconductors, AI, and electric vehicles powering the country to success, but the value of studying philosophy, art, or foreign languages rarely receives the same attention. Non-STEM graduates are left unwanted, unloved, and scraping the barrel for jobs. “There is a hierarchy for academic disciplines, and liberal arts majors are at the bottom,” Zheng says ruefully.

All graduates, regardless of major, have faced a difficult job market over the last few years. As China’s economy slowly recovered from the Covid-19 pandemic in 2023, a record 11.58 million people graduated from Chinese universities, nearly 1 million more than the previous year. Meanwhile, the urban youth unemployment rate for 16 to 24-year-olds hit 21.3 percent in June last year. For liberal arts graduates, the unemployment rate may be higher, while wages are often lower.

According to Liepin, a recruitment platform, the most common graduate job postings on its website in the first half of 2023 were in fields like energy production, machinery operation, and electronics, most of which require a degree in a science subject. Starting salaries are high, with jobs in “smart manufacturing” offering an average of 330,200 yuan annually. For graduate positions that don’t require science degrees, like in human resources, annual salaries tend to be around 80,000 yuan according to a graduate salary report released by education analysis platform Xinchou.com.

When Zheng interned at a university research institute during her studies, she found that the salary for a full-time job in her role doing industry research and strategy could be half or two-thirds lower than technical researchers working in a lab. “I don’t have their technical expertise. They are much more difficult to replace,” she tells TWOC.

Destined to be boot lickers?

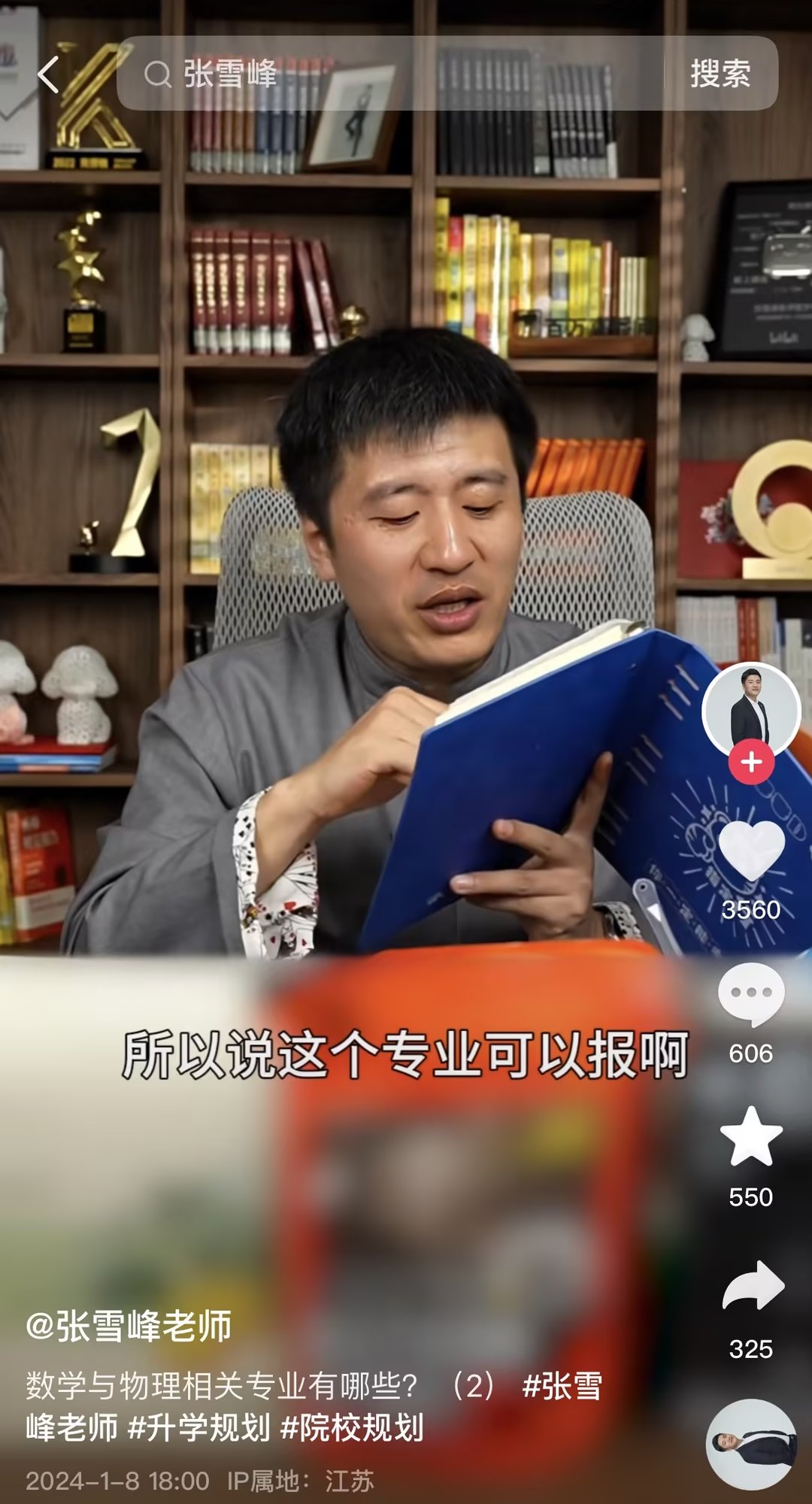

With poor employment prospects, the reputation of humanities degrees has sunk to new depths. In December, prominent education vlogger Zhang Xuefeng urged his 23 million followers on Douyin (China’s version of TikTok) to study science, saying “Liberal arts students all work in the service industry, and lick people’s boots to earn money.” His comments caused a storm, with a related hashtag earning over 370 million views on Weibo. Zhang eventually apologized on his Weibo account. But earlier in the year he made similar comments, such as “If your child wants to choose journalism as a major, you must knock them out.”

Many Chinese universities have reduced their admission score requirements for journalism programs in response to falling demand. At Communication University of China in Beijing, the ranking students from Zhejiang province needed to join the school’s journalism program fell from 4,798th in 2022 to 6,887th in 2023, indicating that demand fell and students with better scores preferred other majors. This trend extends across the country, including all over Zhejiang and at Jiangxi Normal University, where the admission score required to enroll as a journalism student dropped by 19 points between 2022 and 2023. Other liberal arts majors, like many foreign languages and public utility management, suffered similar fates recently.

In April 2023, two of the top three majors removed by universities due to poor enrolment rates or low employment prospects were liberal arts subjects: Public administration was withdrawn by 23 universities, and marketing by 22. According to the state-owned China Daily, the top five most popular majors in 2013 were all liberal arts subjects, while in 2022 they had been replaced by big data, mechanical engineering, electrical engineering, and AI, which had occupied the top spot for three consecutive years.

Many people, even some liberal arts graduates, agree with Zhang that STEM degrees offer better career prospects. “Many liberal arts educations are too superficial, and the knowledge taught in class has little connection to real industry,” Zheng tells TWOC.

“Our college education has a huge problem, it is seriously out of touch with society,” says 27-year-old Yang Lu, a history graduate from Nanjing University who runs a recruitment business that also offers career advice to liberal arts students. “Even the teachers who teach career planning and employment skills don’t have any workplace experience themselves. In a school environment, students can barely get any first hand information from real industry and society.”

Yang runs an account named “Liberal arts students have no way out” with over 170,000 followers on Xiaohongshu (an Instagram-like platform), where he vlogs about employment prospects for liberal arts students.

Another reason for liberal arts students’ difficulty finding jobs, Yang argues, is that the general “expansion of universities has led to an overabundance of highly educated workers.” In 1999, China’s Ministry of Education began rapidly expanding higher education enrolment to provide a skilled workforce for a rapidly growing economy. In 2022, the number of students enrolled at higher education institutions reached 46.5 million, up from around 1.6 million in 1999, and 34.6 million in 2013. While new jobs absorbed many of these highly skilled workers in the past, the supply of graduates now far outstrips demand from employers.

China’s economy also contains a vast industrial sector that makes up nearly 40 percent of the country’s GDP. The service sector, which employs many liberal arts graduates as, for example, consultants, PR workers, and marketers, accounts for around 55 percent of GDP, far below the level in the US (80 percent) or Japan (70 percent).

Some believe workers in non-technical roles are also less secure. “For liberal arts students, when the economy does badly, their positions in communications or management will be the first to face layoffs,” says Yang. When Zhang Xuefeng apologized for denigrating liberal arts degrees, he maintained that “based on the consideration of employment prospects, I suggest that students choose majors that have professional barriers,” referring to specific knowledge and accreditation needed for occupations like doctors, engineers, or lawyers, because they arguably offer more secure employment prospects.

Getting technical

With prospects for humanities graduates so poor, some are making late decisions to change career paths. Chen Xiyun graduated with a journalism degree from Inner Mongolia Normal University in 2021 but has since started studying for a master’s in managerial science at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, an institution renowned for its STEM programs. Chen deliberately chose an academic advisor with an engineering background. “This is an age of fast technological development, so it’s necessary to equip myself with technological knowledge,” she tells TWOC.

While she started by following her passion, she later realized salaries in media are low and now wants to become a computer programmer. According to Boss Zhipin, a recruitment website, the salary for a recent graduate software developer in Beijing is around 25,000 yuan per month, while journalists in China make an average of 4,500 to 8,000 yuan per month according to Jobui, another recruitment platform.

Chen first felt the discrimination against non-STEM subjects in high school, when she had to choose between pursuing the liberal arts track (which includes history, geography, and politics) or science track (physics, biology, chemistry, and more advanced math) for her college entrance exam. High school students choose their track when they are around 15, with twice as many entering the science exam compared with the liberal arts version. Chen was more interested in liberal arts but took the science route under the influence of her parents and other relatives (who all studied science majors). Her parents hoped she would study finance or architecture at university, but she eventually chose journalism.

Chen’s late switch to STEM subjects is no guarantee of employment or satisfaction at work. Biology, chemistry, environmental science, and materials science, for example, have recently been dubbed the “four trap majors” for their perceived failure to teach students practical workplace skills and poor employment opportunities. Twice in the last five years, MyCos Consulting Institute listed Chemistry, Applied Psychology, and Mathematics Education as “red card majors” that have high rates of unemployment, low salaries, and poor job satisfaction among recent graduates. It’s not just majors that impact employability, universities also play a role. Top schools like Tsinghua University have employment rates around 98 percent, regardless of major, while at the obscure Tiangong University 1 in 4 students are unemployed soon after graduation.

Wang Dongyang, a 25-year-old from Henan province with a degree in mechanical engineering from Shanghai University, eventually switched to liberal arts. He spent three years trying to pass China’s postgraduate entrance exam to study for a master’s in journalism. Originally, he was influenced by the common stereotype that boys are better suited to STEM subjects and chose the science track in high school. “The atmosphere in our school was a bit disdainful towards liberal arts. The good students chose to study science,” he says. “Traditional thinking also suggests it’s important for a man to earn a living for the family. However, the poor salary for liberal arts students can hardly achieve this,” Wang says.

Now though, Wang has become more idealistic and driven by the dream of becoming a sports journalist. “Some people believe that humanities can teach you nothing, but I don’t agree. It gives you something subliminal,” he says. “For example, while science and engineering subjects teach you to think of a problem in terms of a single point, liberal arts enable you to be actively thinking and open-minded, which brings you new angles.”

Zheng Xinyue agrees. “I’ve always liked liberal arts because of the presence of creativity…That’s why I don’t want to enter the internet industry in the future, because I still want to be involved in creative work, producing things that others haven’t,” she says. Zheng eventually found a job at an advertising agency in Shanghai where she is paid 10,000 yuan per month.

Well-rounded students

While authorities remain keen to develop the technologies of the future, they have tried to encourage more balanced university programs for both science and liberal arts students. “We need to transition from traditional liberal arts education to a broader perspective of comprehensive liberal arts. We need to foster innovative talents instead of single-area experts,” Professor Wang Ning, Dean of the School of Humanities at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, told the state-owned Guangming Daily in 2022. “While studying liberal arts may not yield immediate economic benefits, a perspective from a liberal arts scholar or thinker can change people’s ways of thinking and even have a revolutionary impact on the methodology and research paradigm of science.”

In 2018, the Ministry of Education proposed introducing “new liberal arts” to universities which aims to bring liberal arts teaching into the context of a high-tech society (and modern Chinese socialism). More universities began offering interdisciplinary programs in response. Beijing’s Communication University of China started a Computational Advertising major in 2021, while Tongji University in Shanghai offers elective courses in science, technology, and mechanical engineering to students majoring in foreign languages or design.

Yang believes another solution is to “reduce the number of admissions to higher education and increase vocational education” to provide new routes to employment opportunities. In 2020, the Ministry of Education issued a plan to increase the size and societal standing of vocational education to be on par with academic education.

However, that would likely push more people away from studying philosophy, art, or history, subjects that Chen Xiyun still values, despite her new computer programming ambitions. “While science and engineering help build cities and railways, liberal arts tell society where to go and how to live with dignity,” she says. “Especially when technology in modern society develops so fast, liberal arts can provide a balanced calming and slowing down effect.” She hopes her next potential employer sees it that way too.

Bottom of the Class: The Woes of China’s Liberal Arts Students is a story from our issue, “Education Nation.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.