The Jimei × Arles International Photo Festival celebrated its 10th anniversary in Xiamen earlier this month, yet the organizers are still struggling to engage local audiences

The main venue of the Jimei × Arles International Photo Festival looks like an old-fashioned business center. Images exploring various themes—from the US-Mexico border to the similarities between pine trees from different regions—are displayed on foam boards, giving the exhibition a more trade-show-like look. The lighting casts a stark, dim glow, lending the space a cool, almost detached atmosphere. The setup stands in striking contrast to the vibrant, hot, and humid subtropical climate of Xiamen, Fujian province—not typically recognized as a major hub for contemporary art—where the festival unfolds.

The annual festival, a sister event to the world-renowned Rencontres d’Arles Photo Festival in France, concluded on January 12. Marking its 10th anniversary this year, the festival showcased works by artists from both China and abroad, including contributions from Spain, India, Japan, and the US. Taking place in Jimei, a district in the southern coastal city of Xiamen, the month-long festival has become one of the top photography events in China, attracting over 500,000 visitors in the past decade. The Jimei × Arles Discovery Award, judged by a committee consisting of renowned artists and scholars, has become a platform for young Chinese photographers to gain recognition.

However, being a successful international photography event hasn’t had much effect on the local art ecosystem. Few notable contemporary art institutions have emerged in the past decade. Local audiences remain disengaged due to the festival’s limited outreach and increasingly esoteric content that feels detached from everyday life. Although organizers have introduced initiatives in recent years to better engage locals, the journey toward fostering deeper community involvement and building a sustainable art culture remains uncertain.

Photographer Lu Zhirong, better known as Rongrong and a co-founder of the festival, has a long history with the French. His first solo exhibition was held in 1997 at the French embassy. “No one saw photography as a form of art in China at that time,” Lu tells TWOC. After establishing himself as a photographer on the international stage, he opened the Three Shadows Photography Art Centre in Beijing in 2007. Hoping to connect more Chinese photographers with the international community, Lu sought collaboration with Rencontres d’Arles and brought the festival first to Beijing in 2010. In 2015, with support from the Xiamen local government, the collaboration evolved into the annual Jimei × Arles International Photo Festival in Fujian, Lu’s hometown. He hoped that the festival could invigorate the city, much like how the Rencontres d’Arles transformed Arles, a forgotten historical city just 50 years ago, into a summer destination attracting over 100,000 visitors every summer over the last decade.

Read more about contemporary art in China:

- Framing Contrast: Photographer Yan Jiacheng on the Search for Authenticity

- Beyond the Frame: Shuare Shizhu’s World in Wide Strokes

- Collecting Trends: How Middle Class Buyers Influence China’s Art Market

Yet 10 years in, the annual festival remains a relatively niche event for locals in Xiamen. Zhu Lanqing, a Xiamen-based photographer and a regular visitor to the Jimei × Arles for the past decade, observed that most of this year’s 60,000 participants were art industry professionals and media members who flew in from across the country. The number of local audiences was limited, partly because its location was not convenient for the public. Most Xiamen residents prefer to stay on the main island, while Jimei, situated off the island in an industrial area, has yet to become a destination that draws the general public for exhibitions. The Three Shadows Art Center Xiamen, a major venue of the exhibition, is tucked away on the third floor of an office building and is easily overlooked by passersby.

Moreover, the experience of visiting Jimei × Arles differs greatly from that of Rencontres d’Arles. As Zhu recalls, the exhibition venues of Rencontres d’Arles are spread throughout the town, including former industrial buildings, churches, museums, and places locals regularly visit, all within walking distance. She marvels at how the displayed pieces are integrated into their backgrounds, taking on various forms, sizes, and themes. “It’s not just about viewing the artworks, but about experiencing how the artworks interact with this unique space.”

Known for integrating its rich cultural heritage with contemporary photography, Rencontres d’Arles serves as an industry model for how art festivals can inspire audiences to explore and connect with different parts of a city. This approach has influenced many other events in China, including Lianzhou Foto, another international photography festival in Guangdong province. Situated in Lianzhou, a remote city deep in the Nanling karst mountains, Lianzhou Foto has been acclaimed for rejuvenating the old town by turning its former rice warehouses and a shoe factory into exhibition venues. In 2017, the festival took its mission further by building a photography museum in the heart of the city, just steps away from a local primary school. Walking between galleries, visitors might pass by residents drying cured meat and quilts across the street, while neighbors in the arcade buildings wave and greet.

In comparison, most of Jimei × Arles’s exhibitions were set up in a modern building. “The presentation is rather condensed, instead of providing a flowing experience,” Zhu says. She feels pity that as a city-wide festival, it didn’t utilize many important locations in Xiamen.

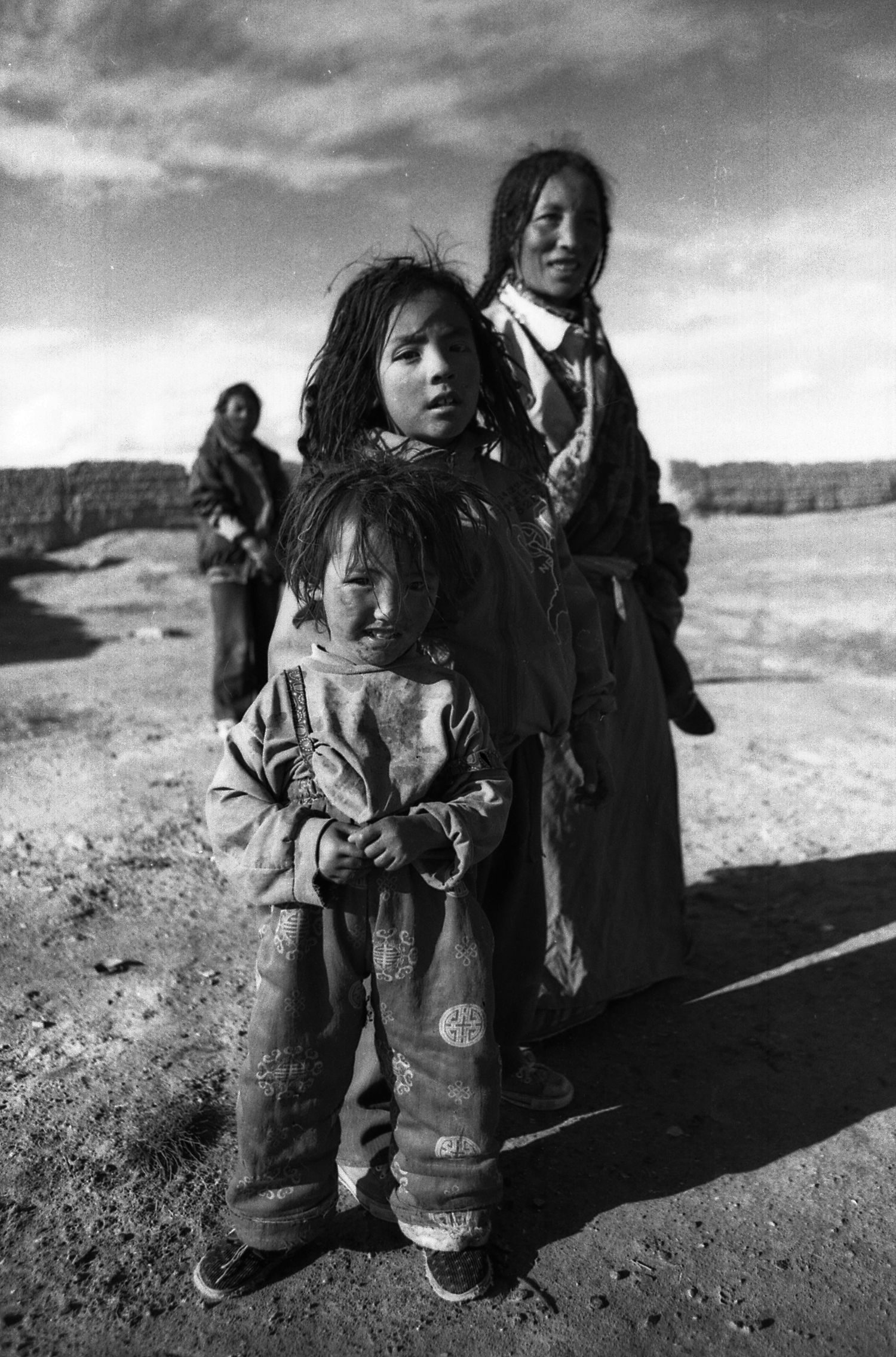

Apart from the exhibition venues, Jimei × Arles’s content has also been criticized for not appealing to the general public. Li Jiadong, a local university student and intern at the Three Shadows Photography Art Centre Xiamen, speaks highly of his early experience attending the festival years ago, when he was constantly inspired by works focusing on public events, rural traditions, and the local living environment in Minnan, a region in southern Fujian. For example, in 2021, a featured photographer in the Jimei × Arles Discovery Award, Guo Guozhu, turned his lens to document villages across the country abandoned due to urbanization, while another photographer-journalist, Zou Biyu, captured the apartments and shattered middle-class dreams of their owners affected by the Tianjin Port explosion in 2015.

As a college student from Tianjin, Li feels that his early experiences at Jimei × Arles transformed his view on photography: It could be so diverse, empathetic, and directly connected to everyday life. However, he has observed a decline in the festival’s public relevance over the years. The exhibitions this year, such as immigration through Central America and the everyday sculptures adorning rooftops in rural Punjab, India, feel far too detached from local everyday life, he says.

“Chinese audiences aren’t incapable of understanding these topics,” Li explains, “but many believe there are more pressing concerns within China that need attention.” Walking through this year’s Discovery Award exhibitions—many of which gave off art school vibes and featured vague explanations—he felt a growing sense of disconnect.

In recent years, the festival has tried to rectify this problem. The Isles Project, launched in 2023, invites local curators to design city walk routes, leading participants to discover cultural and artistic spaces while visiting roaming exhibitions. Liu Mengting, the executive director of the Isles Project, tells TWOC that the initiative aims to attract a wider audience beyond contemporary art professionals by placing exhibitions with less specialized content in easily accessible, everyday locations that residents often pass by.

“Make Friends, Not Art,” one of the five Isles Project roaming exhibitions this year, unfolds in Dashe, a 700-year-old village in southeastern Jimei. The exhibition weaves together stories of young new residents building a shared life through photography, video, illustrations, and installations.

One of its venues is a local grocery store, a popular hangout spot for residents. Its glass walls have naturally become a community bulletin board, displaying posters ranging from homemade chili sauce advertisements to announcements for local literary events. In front of the store, an installation piece—oyster shells adorned with poster images created by Dashe residents—is displayed, symbolizing their friendship and shared living.

Community art efforts in Dashe have not always gone smoothly. Last year, an exhibition faced resistance from older residents when the curatorial team hung photographs on the village’s ancient trees. Guo Qikuai, one of the curators, recalls an elderly man who repeatedly removed the photos when no one was attending, saying he didn’t want “strange things” on the tree he had known since childhood. “When it comes to understanding contemporary art and its concepts, there is always a divide between the older and younger generations,” Guo notes.

Carol Lu, an art historian, curator, and director of the Three Shadows Image Curation Workshop, points out that compared to audiences in Western cities with established contemporary art traditions, Chinese audiences—particularly those outside of major metropolis—still need time and opportunities to grow and engage with the art. This is a common challenge for many contemporary art exhibitions in China, and therefore requires art institutions to make proactive, targeted efforts to guide their audiences. She adds that the public impact of an exhibition cannot be measured solely based on current levels of public participation, as a decade-long exhibition of international standards inevitably broadens the vision of the younger generations, as well as producing a subtle yet significant influence on the local government’s cultural policies.

Zhu, who curated an exhibition focused on local food for last year’s Isles Project, believes that the initiative is a step in the right direction, as it allows audiences to engage with the photography festival and truly connect with Xiamen. However, Li, the volunteer, feels that the initiative is more of a public relations move to better the festival’s image than one focused on promoting public accessibility. Some of the participating stores simply have photos taken with phones stuck on their windows and posters on their front doors, making the stores look prettier and attracting more tourists to “check-in,” Li says. It’s worth noting that this year’s Isles Project was co-launched by the social media platform Xiaohongshu.

Despite his issues with the festival, Li still plans to return for Jimei × Arles every year in the foreseeable future. For him, the festival remains an invaluable window into the international contemporary art community in an era of increasing geopolitical tension and rising isolationism worldwide. “As long as they have the final say when it comes to the selection of awards and exhibition content, without being swayed by sponsors, it won’t be too bad,” Li says.

All images courtesy of Jimei × Arles International Photo Festival