A look at the recent hits and misses in female-centric cinematic sphere

Chinese cinema has seen a resurgence of women-centric movies in the past year. Among the standouts, YOLO dominated the box office this spring, with director Jia Ling becoming one of the first female directors to achieve a top-grossing movie of the year. But YOLO isn’t alone. Here are three other films focusing on womanhood that caught our attention.

Her Story《好东西》

After the official release of Her Story, a lighthearted rom-com directed by Shao Yihui, on November 22, over 65 percent of nearly 320,000 viewers gave it a perfect score. The film was praised for its unconventional yet insightful portrayal of womanhood and female friendship, making it the highest-rated film of the year on China’s major review platform Douban, earning a score of 9.1 out of 10.

Her Story was marketed as a sister flick to Shao’s previous film, Myth of Love (2021), an urban romance set in Shanghai. A critical and popular success, Myth of Love resonated with audiences for its sharp wit and feminist themes, seamlessly woven into its romantic comedy structure.

The long-anticipated Her Story is a slice-of-life comedy about two women and their day-to-day struggles. Wang Tiemei (Song Jia) is a determined and strong single mother of a daughter who moves into her new home, befriending her optimistic neighbor Xiao Ye (Zhong Chuxi). The two vastly different women deal with the chaos created by their respective romantic and family lives, but are ultimately united in their understanding of each other’s pains and struggles.

Read more about female-centric Chinese movies:

- Remembering the Chinese Women Who Danced for the World

- The Rise of Female Perspectives in China’s Movie Industry

- The Female-Perspective Films Enriching Chinese Cinema

At its core, between the comedic tone and quippy one-liners, the film dissects and addresses misogyny and patriarchy not as individual occurrences or biases, but as a systemic issue that takes root even in the most well-meaning of people. The film is unafraid to tackle subjects of women’s reproductive health and sexual objectification; in one scene, Tiemei’s date tears her undergarments in the process of getting intimate. When questioned, he says simply that this is how adult movies portray sexual intimacy. Another scene features Tiemei’s daughter openly discussing menstrual cycles without shame, and Xiao Ye combating the idea that women should consume brown sugar and water for their cramps and tolerate the pain they endure.

While these moments are played for comedic beats in the promotional material and the film, there are serious issues being presented here, without becoming overly preachy or moralistic.

The film has drawn comparison to the likes of Greta Gerwig’s Barbie for its biting but comedic commentary on modern womanhood, while using a grounded approach centered on flawed yet sincere women.

The Unseen Sister《乔妍的心事》

The thriller genre has quietly but steadily added entries to the box office list each year. Released this October, The Unseen Sister ratchets up suspense and tension with its gritty, realistic setting, as director Midi Z draws on his birthplace, Myanmar, to explore the contrasting lives of two sisters.

Qiao Yan (Zhao Liying) is a famous actress who is suddenly visited by her estranged and pregnant older sister, Da Qiao (Xin Zhilei), seeking her out to help pay back a debt. It is revealed that Qiao Yan actually has no legal identity in China, and has been using her older sister’s, who had given it up when she left for Myanmar as a teen with her boyfriend. The rest of the film portrays the dangerous push-and-pull between the sisters as one desperately craves the life of the other—and the other attempts to rid herself of her secret.

The film touches on issues of childhood abuse, sexual harassment, and assault in the entertainment industry. It opened to mixed reviews and a mediocre box office, with many criticizing both the confusing story and panning the actors’ performances as lifeless and dull. The film does win a few points, though, by giving its two central women characters depth; it’s unfortunate that more couldn’t have been built on this solid foundation.

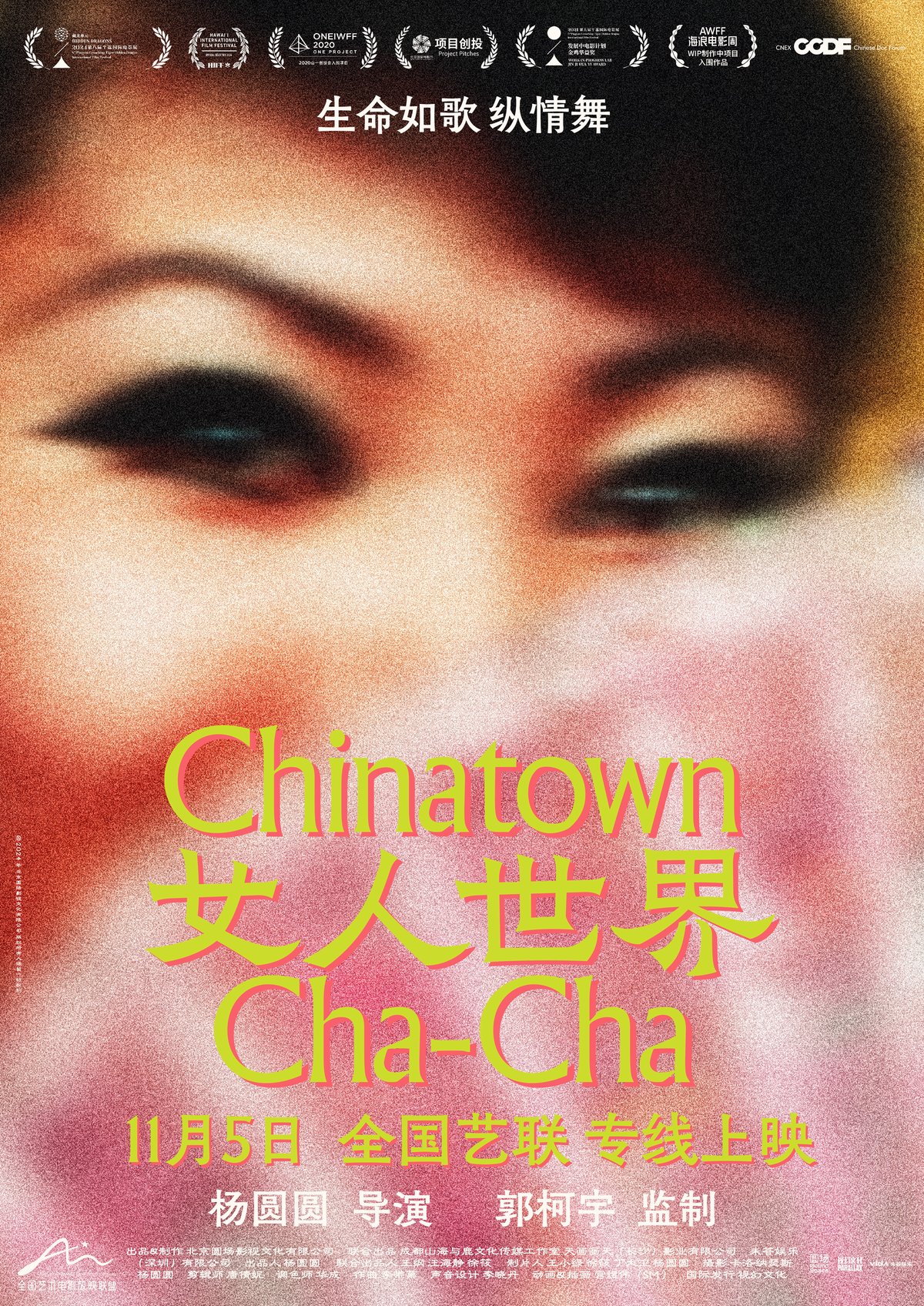

Chinatown Cha-Cha《女人世界》

An opening sequence of spotty old black-and-white films takes us into a different era. The quick transition into the lively brightness of San Francisco’s Chinatown—where young Chinese burlesque dancers perform for a delighted crowd—takes us to a different place. The music cuts. Away from the flashing lights and bedazzled young women, we see an older lady doing her makeup, checking off a list of packed items, and zipping her suitcase.

And away we go.

Subdued and intimate but full of life and motion (and glitter), Yang Yuanyuan’s documentary Chinatown Cha-Cha is an introspective reflection on the life and career of former burlesque dancer Coby Yee, and a celebration of changing eras and lives.

Yee began her career in San Francisco’s Forbidden City nightclub in the 1940s, garnering a reputation as “China’s Most Daring Dancing Doll.” Yang’s documentary, shot between 2018 and 2020 (until just before the Covid-19 outbreak), takes us through 92-year-old Yee’s final journey with the Grant Avenue Follies, a burlesque dance group comprising senior dancers. Across the 85 minutes of runtime, Yang’s narrative reflects the vibrancy of the women’s lives, their love for dancing, and Chinese diaspora cultures across time.

While Chinatown Cha-Cha looks back on a forgotten era, it also introduces a new perspective: the story of Chinese diaspora womanhood as told by Chinese diaspora women. The theme of connection plays throughout the documentary, including the cultural connections that Yee’s parents sought in Cantonese opera and the ones that Yee found in her outlandish, Chinese-inspired stage costumes. The Follies’ world tour also seeks connections at every stop: In Cuba, the dancers find a dissipated Chinatown and a dwindling Chinese community, which is reinvigorated by the Follies’ performance with local Chinese opera singers; in Shanghai, Yee reflects on her father’s life in his homeland.

“Evocative” would be the word to describe Yang’s use of cinematography, bringing humanity to her subjects. As viewers, we’re used to seeing documentaries simply as sources of objective fact and information, but Yang opts for intimacy and subjectivity. Audiences can read over Yee’s shoulders as she reminisces, flipping through an old photo album of her posters and pictures; observe the still moments as the Follies set up a social dance event in San Francisco; or walk with Yee and her partner Stephen King as they stroll hand-in-hand in Chinatown. Between the shots, Yang utilizes jazzy swing music and fast-paced archival footage of dancers and the nightclub, contrasted cleanly with the crisp images of older women in moments of quiet, casual leisure, where only the glimmer in their gaze remains as lively as before.

Yee and the Follies’ journey ends in China, with a final performance. Yee dons her extravagant Las Vegas headdress, and there is a poetic sense that this odyssey has come full circle. As the curtains close, they celebrate not only the success of their world tour, but of the life and times of the ones who came before: their hardships, their heritage, and their passion.