Yang Niuhua, who was kidnapped when she was 5 years old, is on a mission to help victims unite with their lost families. But first, she seeks justice against her own abductor in a trial that has gripped the Chinese public.

The moment Yang Niuhua stepped out of the Guiyang courtroom on October 11 after the seven-hour trial, a flock of cameras and microphones closed in. Behind her, desperate parents clutched red posters with photos of their missing children, hoping for a sliver of TV time, while Yang, who testified in court as a victim, spoke about what she had just witnessed: the retrial of Yu Huaying, the 61-year-old woman accused of trafficking 17 children.

“She didn’t cry, nor did she apologize…All she did was argue with me and the other victims’ parents,” Yang, who first reported the case to the police in 2021 and actively assisted in Yu’s eventual arrest, told state media CCTV News.

The judge did not deliver the verdict Yang and other victims had been hoping for—the court went into recess—but Yang was not discouraged. In 2023, she testified during the initial trial, where Yu was sentenced to death. After Yu appealed, evidence of additional abductions emerged during a second trial, leading to the case being sent back for the current retrial.

“I believe that no matter how many times the case is retried, there will definitely be a good outcome,” Yang, who advocates for Yu’s execution, said in a video she posted on the microblogging platform Weibo on October 11.

Read more about anti-human trafficking efforts in China:

- The Influencers Helping Trafficked Women Return Home

- The Art Exhibition “Breaking the Chain” on Human Trafficking

- A Story of Child Abduction and a Father’s Journey to Find His Son

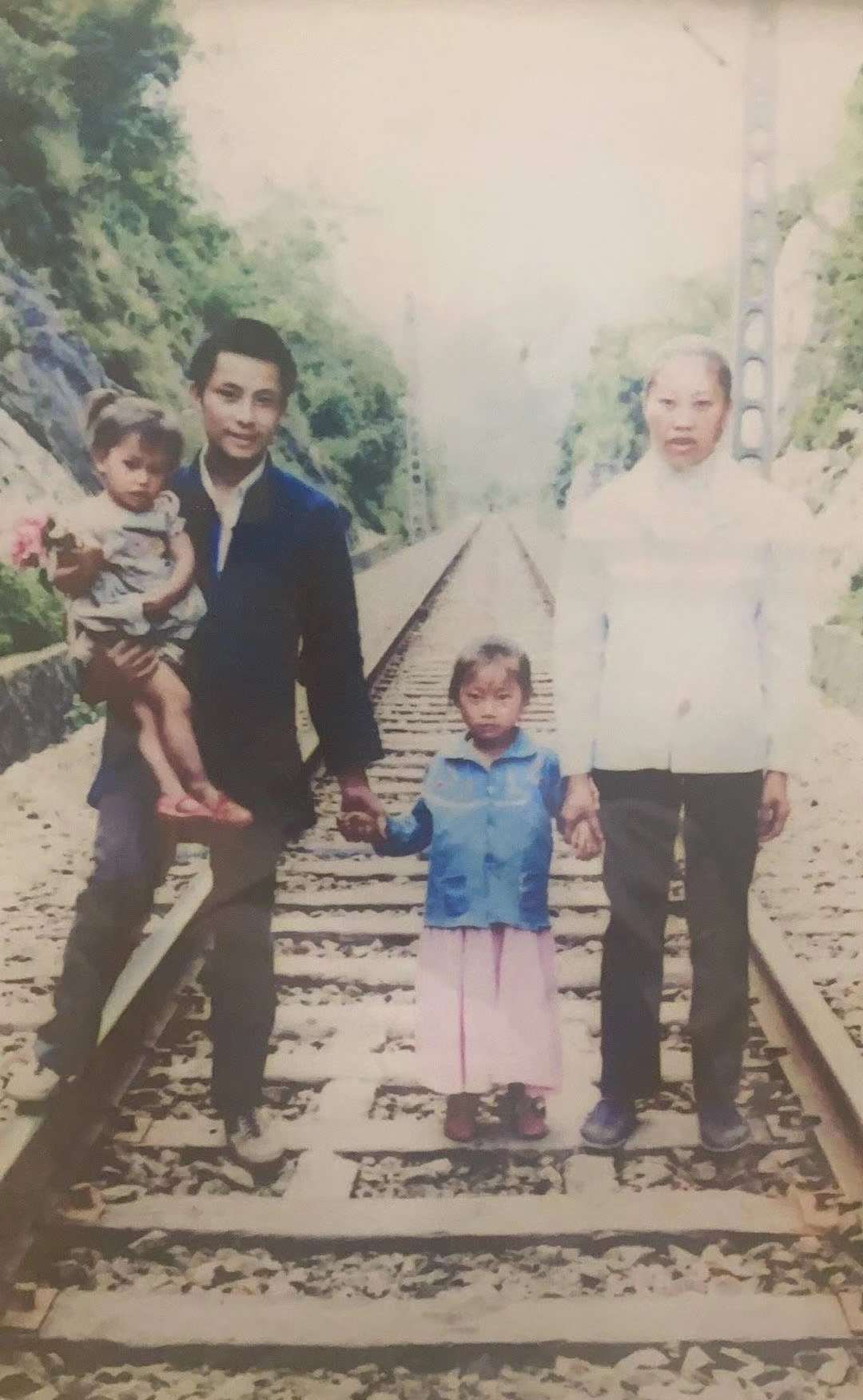

Yang’s hard-line stance is understandable. In 1995, Yu, posing as a kind neighbor, kidnapped Yang and took her to Handan, a city thousands of miles from her home in Guiyang. Yu told her that her parents had sold her for money. Yang was 5 years old. She was sold in Handan for 2,500 yuan to “grandma,” an elderly woman who allegedly bought her to be a child bride for her deaf son. Even though Yang’s adoptive father never behaved inappropriately toward her, her life in her new “home” was difficult. The often abusive “grandma” changed her name to Li Suyan and made her drop out of school before she finished sixth grade.

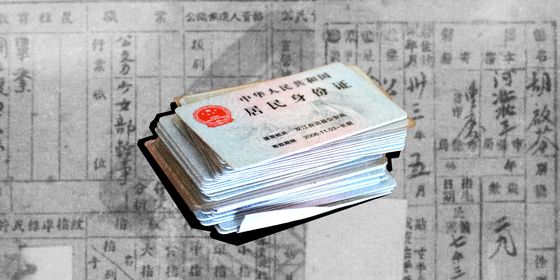

Yang eventually moved to Jiangsu to find work and started her own family in 2009 after “grandma” passed away. Yang never stopped wondering about her biological family. In 2012, encouraged by her supportive mother-in-law, Yang registered her blood sample in the national DNA database for combating human trafficking, set up by authorities in 2009.

For nearly a decade, there were no leads, much like in the thousands of heart-wrenching and unsolved abduction cases from that period. According to a 2020 study published in the academic journal Population Research on child trafficking in China, the abduction of young girls peaked in the 90s, with nearly 800 reported cases each year, mainly taking place in Guizhou (Yang’s hometown) and Chongqing. Most of the girls were trafficked to rural areas as child brides or forced into prostitution.

It wasn’t until 2021, when Yang started posting videos on Douyin, China’s version of TikTok, that a glimmer of hope emerged. Her cousin stumbled upon one of the videos and connected Yang to her biological sister.

But Yang’s long-awaited family reunion, the one she had dreamed about for nearly 30 years, led her to even more heartbreak than she could ever imagine. “I thought my parents didn’t come looking for me because they were divorced and formed new families…or they really sold me for financial gains,” Yang told The Voice of China, the flagship radio channel of China National Radio. In reality, her parents, devastated by the loss, died two years later after spending all their savings trying to find her. Her mother was 32 and her father 38 at the time, leaving her older sister an orphan at 11.

Kneeling before her parents’ grave, Yang broke down in sobs. “My parents were so young, and they’ve been lying here in the mountains all alone for 20 years…I made up my mind at that moment—I need to find the trafficker and avenge my parents,” Yang said during a public speaking event organized by Portrait magazine.

Yang immediately tried to file police reports in both Handan and Guiyang, putting her beauty salon in Handan on hold to assist the police with the investigation. Despite her young age when the abduction happened, Yang remembers the painful experience with detailed clarity. She could recall the name of her trafficker and the hateful expression on her face. She tracked down the mediator of her sale, a man surnamed Wang, and begged him to testify in court. “You’re already 90 years old. You’ve lived 60 more years than my parents,” Yang told him.

In June 2022, after multiple trips between Guiyang and Handan, Yang made it happen—the Yu Huaying child trafficking case was filed in Guizhou. She identified Yu’s printed photo from a lineup of more than a dozen faces. “I’d recognize her even if she turned to ash,” Yang told CCTV. The authorities tracked Yu down 24 days later. She was playing mahjong when the police apprehended her in Chongqing.

Yu’s official trial started on July 14, 2023. As more evidence came in, the public became outraged to discover how Yu used her own daughter as bait to abduct children, and how she showed little remorse during the court proceedings, instead pinning the blame on her husband and a third person, her lover, who helped facilitate the sales of the abducted children. With evidence of 17 abductions from 12 families between 1993 and 2003, most observers believe the retrial will affirm Yu’s original death sentence.

Yang also filed a civil compensation claim of 8.8 million yuan, which includes death compensation, emotional distress damages, and lost wages. She knows she’s unlikely to receive much money even if she wins, but, as she told CCTV, “I want everyone to know…she must pay the price for her actions.”

In recent years, China has made strides in combatting human trafficking, with more high-profile cases like Yu’s making the headlines every year. In 2016, the Ministry of Public Security launched the Emergency Release Platform for Missing Children Information, also known as the Reunion system, similar to the Amber Alert in the US. The platform has recovered 5,113 children over the past eight years, achieving a recovery rate of 98.5 percent. In 2021, the Ministry of Public Security also carried out the “reunion operation,” which recovered 4,142 missing trafficked children, including a case that spanned 61 years. The operation solved 206 cold cases of child trafficking and apprehended 543 trafficking suspects, according to Xinhua News Agency.

While Yang—along with a watchful public—waits for the final verdict, she has continued to use her platform to help those searching for their lost family. She regularly posts videos on Douyin, where she has more than a million followers, to help other parents search for their lost children. The police have also established a blood sample collection point at Yang’s salon. She will ship the samples to the local police station, where the information will be entered into an anti-trafficking DNA database.

As Yang said at the Portrait magazine event this March, “I truly hope that our family’s tragedy doesn’t happen again.”