Canadian literary critic Dylan Levi King examines how Can Xue, who has thrived outside the Chinese literary system, has emerged as a frontrunner for this year’s Nobel Prize in Literature

When it comes to predicting the annual Nobel Prize in Literature, literary merit isn’t the only—or even the most important—criterion. Instead of evaluating the career or genius of individual writers, sometimes it can be more instructive to guess the sociopolitical mood at the Swedish Academy, shifts in literary taste, or patterns in how the Nobel has been awarded.

For several years in a row, bookmakers have put Chinese writer Can Xue at the top of their list for possible Nobel Prize winner. This year, she is an almost unanimous favorite, ahead of Gerald Murnane, Anne Carson, Lyudmila Ulitskaya, and even the most recognizable names, like Thomas Pynchon, Salman Rushdie, and Margaret Atwood.

But does she deserve to be the winner, with the announcement coming on October 10?

Born in Hunan province as Deng Xiaohua, the 71-year-old is known for experimental novels influenced by Jorge Luis Borges and Franz Kafka. Her nom de plume, Can Xue, describes snow that remains unmelted in deep canyons or on mountain peaks.

It’s difficult to characterize her work—though primarily a short fiction writer, her novels showcase her finest writing. A surrealist, she describes life in suffocating, strange societies, and occasionally, she is funny.

To call her obscure would be an insult, since she has a devoted fanbase, especially among writers and critics. Her low-key fame has endured innumerable trends. But she is not a literary superstar in China. She has never been nominated for the country’s Mao Dun Literature Prize and Lu Xun Literature Award, though that could count in her favor when it comes to the Nobel.

As early as 1986, when Swedish Sinologist Göran Malmqvist visited Shanghai to speak at a conference of the Writers’ Association about China’s Nobel prospects, he made it clear that the Swedish Academy was looking for things that the literary bureaucracy was not—namely, brilliance outside of the system.

It would not be accurate to describe Can Xue as a dissident writer, but she has thrived outside of the Chinese literary circle. She is rare among contemporary Chinese writers—except for those who write in foreign languages or live abroad—for having been more famous abroad almost since the beginning of her career.

In certain circles, her books like Frontier, translated into English by Karen Gernant and Chen Zeping, a mind-bending anti-narrative about a village called Pebble Town, and the disorienting, surreal romance The Last Lover, translated into English by Annelise Finegan Wasmoen, are considered among the greatest works of literature in this century. She has been profiled in the New Yorker and published fiction in the London-based literary journal Granta.

Read more about overseas Chinese writers:

- The Simple Lines and Grand Designs of Shangyang Fang’s Poetry

- Geling Yan’s “The Secret Talker” Toys with the Unreliability of Words

- Xiaolu Guo Explores Belonging and Authenticity Through the Language of Lovers

Malmqvist also emphasized the importance of exquisite translations—something Can Xue has in abundance. Her fame was built off translations, earning her a name in Europe as a serious writer before local critics caught up with her oeuvre. Her short fiction was translated into English in the late 1980s, French and German in the early ’90s, and—crucial to writers hoping to win a Nobel—into Swedish in the 2000s.

Aside from those factors—thriving outside the system, being translated often and well—Can Xue has other more ephemeral qualities prized by the committee.

Her literary output is unique. During a blossoming of literary fiction in the ’80s and ’90s, China produced a great number of muscular, satirical critical realists such as Yan Lianke and Jia Pingwa, skilled historical fantasists such as Zhang Chengzhi and Han Shaogong, and some of the world’s finest poets, such as Mang Ke. Like other writers of her generation, Can Xue blended Western modernism with local tradition, but did things with that recipe that nobody else could. No one could match her hazy, philosophically-rich avant-garde post-socialist world. She is clearly possessed by genius. Like fellow Nobel nominees Carson and Murnane, she seems to exist at this point in history without peers.

Most importantly, to the Swedish Academy, Can Xue is nearing the end of a brilliant career that has not been sufficiently celebrated by other prizes: apart from being long-listed for the Man Booker International Prize a couple of times, her work has been overlooked by both Chinese and international prize juries.

Weighing up other factors to the horse race, there is pressure to send the Nobel Prize to Asia. In the previous hundred years, the prize has gone to East Asian writers only five times (Kawabata Yasunari in 1968, Oe Kenzaburo in 1994, Gao Xingjian in 2000, Mo Yan in 2012, and Kazuo Ishiguro in 2017). Neither Korea nor Japan seems to have a likely candidate this year. South Korea’s frontrunner, Ko Un, is somewhat obscure, while Japan’s Haruki Murakami seems to be regarded by the Swedish Academy as not a literary heavyweight.

According to the gender pattern the award usually follows—alternating male and female laureates—this year’s Nobel is likely going to a woman. Canadian poet Anne Carson, the next closest female favorite, could be ruled out by geography.

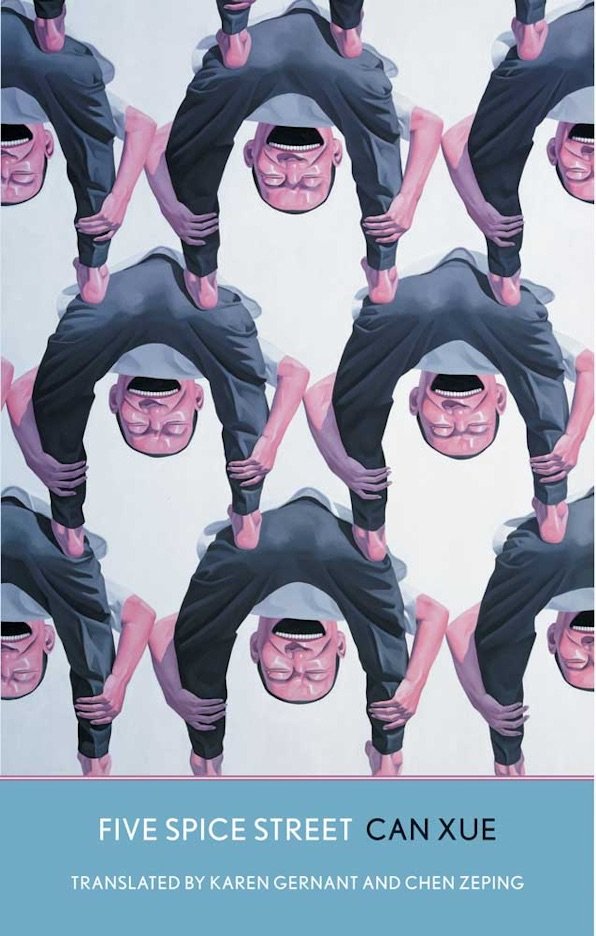

With the announcement just days away, you still have time to get through one of Can Xue’s books and form an opinion. A great place to start might be the suffocating, nightmarish stories in I Live in the Slums, a collection translated by Gernant and Chen. From there, you can slip into Five Spice Street (Gernant and Chen again), her first novel translated into English—a surreal chronicle of backstreet life that could be the work to sway the Swedish Academy.

If her name does not pop up this October, she will enter the 2025 oddsmaking as an even better favorite. Best to do your homework now.

Is China on Track for Another Nobel Prize in Literature After Mo Yan? is a story from our issue, “New Game.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.