From almost the very beginning, video games have drawn inspiration from Chinese literature

A gamer’s pale cheeks reflect the glow of a screen lit by the introduction to the hottest game of the season. For the first time, the player will be in control of Sun Wukong’s famous staff, will crush the skulls of hideous yaoguai, and clear a path to India for their master.

No, this is not a contemporary story. The gamer is not playing Black Myth: Wukong.

It is the summer of 1984. Ronald Reagan is in the White House. The Soviet Union is going to boycott the Olympics. The gamer is standing in an arcade in Osaka, having just pumped a 100-yen coin into a cabinet to play Capcom’s Son Son: Let’s Go Tenjiku, a rudimentary side-scroller based on Journey to the West.

From almost the very beginning, video games have drawn inspiration from Chinese literature.

Journeys to the West

The extent to which the “four classics” of Chinese literature—a quartet of sprawling novels written between the 14th and 18th centuries in vernacular Chinese—has penetrated the culture of the Sinosphere cannot be overstated. Almost immediately after publication, the four books Outlaws of the Marsh (《水浒传》), the Romance of the Three Kingdoms (《三国演义》), Journey to the West (《西游记》), and Dream of the Red Chamber (《红楼梦》) began to be transformed into operas, poetry, and games (most often playing cards illustrated with characters from novels, meant for drinking games), and, later, comic books, TV series, films, and video games.

Capcom’s Son Son was not impressive, even by standards of the day. But it was notable for its source material, and is among the earliest examples of game developers borrowing from Journey to the West. Even the Japanese gamers who hadn’t read the book would have recognized Son Son (a diminutive for Son Goku, the Japanese pronunciation of Sun Wukong) and Ton Ton (a nickname for Zhu Bajie, or Pigsy, one of the other companions on the pilgrimage).

Read more about Chinese gaming:

- Little Tyrants: A Brief History of Chinese Video Game Consoles

- Net Nostalgia: Remembering the Glory Days of China’s Internet Cafes

- Pixel Passion: Stories of Hope and Hustle From China’s Indie Game Makers

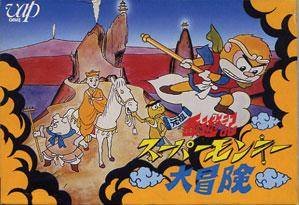

And it spawned increasingly complex descendants, like Taito’s Cloud Master (1988) and Westone’s Saiyūki World (1988). In keeping with the adventure at the heart of the novel, there were also attempts to turn Journey to the West into role-playing games. Few were successful, and some, like VAP’s Ganso Saiyūki: Super Monkey Daibōken (1986) and Nintendo’s Yūyūki (1989), have gone down in history as epic disasters.

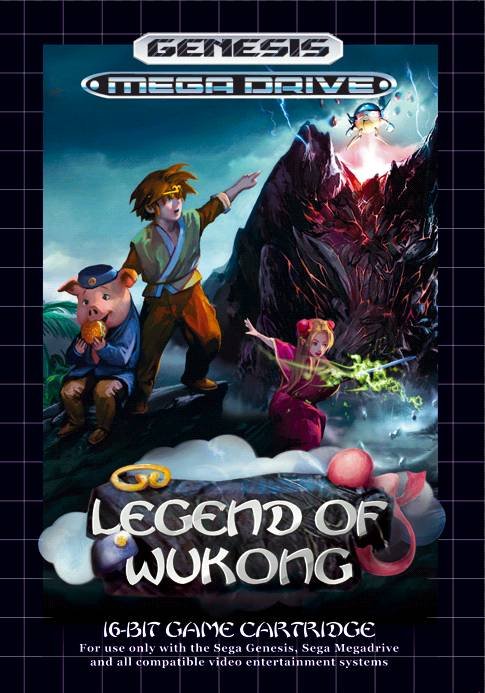

Further afield, developers in Taiwan making games for unlicensed clones of popular platforms flooded the market with low-budget riffs on Journey to the West. These started with crude arcade shooters, but eventually developed into more complex, fully realized games, like Gamtec’s Legend of Wukong for the Sega Mega Drive / Genesis.

Black Myth would not exist without two particular adaptations by Chinese developers: Those were Fantasy Westward Journey by NetEase and Asura Online by Tencent (which the developers of Black Myth worked on). These online multiplayer sensations of the 2010s proved the abilities of Chinese developers to adapt their own literary culture for cutting-edge games.

No love for love?

Journey to the West established itself as a marketable property in the video game world. This is hardly surprising for a fantasy-adventure novel, but the other three Chinese classics have received the same treatment.

Romance of the Three Kingdoms, a gargantuan history of second and third-century political intrigue and warfare, has been adapted more times than Journey to the West. If you meet anybody under 40 with an encyclopedic knowledge of Three Kingdoms, it is more likely that they picked up their factoids about Cao Cao (曹操) or the Battle of Hulao Pass during gaming sessions, rather than by reading the multi-volume novel.

The earliest and still one of the most popular games based on the novel is Koei’s Romance of the Three Kingdoms, released in 1985 for PC-88 and other platforms like Nintendo, Amiga, and MS-DOS systems in the following years, and updated as recently as 2020 (Romance of the Three Kingdoms XIV for the PlayStation 4, Microsoft Windows, and Nintendo Switch). The dense strategy game became a bestseller in Japan.

Koei’s game set the model for how Three Kingdoms should be adapted, spawning numerous strategy games from Japanese and Chinese studios.

The situation for Outlaws of the Marsh was similar: Suikoden, released in 1995 for the PlayStation, told the story of bandits hiding out from imperial forces as an expansive role-playing game, somewhat based on the model of Final Fantasy or Dragon Quest.

Dream of the Red Chamber, a supernatural love story about an effete young man’s affair with his cousin, is arguably the most frequently adapted of the four classics. It has spawned numerous unofficial sequels, television series, and operas, but has received the least interest from game developers.

Read more about adapting Chinese classics:

- Red Alert: The Challenge of Bringing a Chinese Classic to Screen

- How many Journeys to the West have you seen?

It is hard to say whether this is due to the poetic complexity of the novel or the lack of intersection between the demographics of Dream of the Red Chamber readers and the average gamer and developer. Attempts have been made, however, in the form of romance simulations—minimally animated choose-your-own-adventure books—that allow one to play as a suitor of Lin Daiyu or Jia Baoyu.

Among the earliest Chinese efforts to turn Dream into a dating simulator—or, simply, “romance game (恋爱游戏)”—was a Taiwanese developer’s 1998 The Dream of Red Chamber for MS-DOS. While it was pitched to adults, it didn’t sink to the lewd depths of a Japanese follow-up, called Slaves of the Red Mansion, which caused minor furor among gamers furious at the novel converted into softcore pornography. Later, Hong Lou Meng, a 2009 PC game by Beijing Entertainment All Technology, set the mold for many low-budget adaptations: Pitched to young women, the game used the settings and characters of the novel for a fantastic love story only loosely connected to the original plot.

Clearly, Black Myth is one in a long line of adaptations of the four Chinese classics for video games, but it still stands out as an achievement. With a storyline that begins after the close of the original novel, it pushes the envelope of what adaptations can generate from the source material.

More significantly, it is the first big-budget production on a classical literary theme from a Chinese studio. Though Chinese studios had gotten in on the action as early as the 1980s, Japanese offerings dominated the market; it wasn’t until the 2000s that Chinese developers had the resources to compete, and it was only in the last decade that they could beat their overseas rivals. It remains to be seen if Chinese studios go back to this playbook in future attempts to create the “next” Black Myth.