Complicated admissions policies and a cutthroat job market have made college application consultation a lucrative business in China, but the quality of service is often subpar

It was midnight on June 29, three days after the scores of China’s highly competitive college entrance exam, known as gaokao, were released, and the livestreaming channel of Kafka Jing (pseudonym) was still buzzing. Parents and students anxiously sought one-on-one sessions with Jing, an education influencer who has over 313,000 followers on the video streaming platform Bilibili. They were up at the late hour hoping for guidance before making one of the most critical and potentially life-changing decisions: choosing which college to apply to.

“What’s your score? What’s your ranking? What kind of job do you want in the future?” The 28-year-old native of Chengdu fired question after question to each parent or student he got on the line. Sometimes he even asked for the student’s MBTI type just to get a fuller picture. Based on their responses, Jing would cherry-pick a handful of majors based on their interests within the intensely packed 30 minutes, free of charge.

Consultation services like Jing’s, many charging tens of thousands of yuan, have boomed both online and offline in recent years as anxiety over the cutthroat job market grows. Ordinary families are now willing to spend significant amounts of time and money in return for a well-informed decision. However, the quality of this for-profit industry, which is still nascent and lacks significant governmental regulation, has also come under scrutiny.

Read more about education trends in China:

- How A Lifestyle App Shed Light on China’s Education Gap

- Why Many of China’s Teachers Are Leaving the Profession For Good

- The Woes of China’s Liberal Arts Students

The high stakes

The stakes for choosing a school and major are particularly high for students in China. Unlike at US universities, which impose few restrictions on student transfers and where students choose a major after one or two years of study, most students at Chinese universities are locked into a school and major from the moment of acceptance. According to the Ministry of Education, students can only transfer when they face illness, special difficulties, or specific needs that make it impossible to continue studying at their current school. Only a small number of sophomore and junior students can successfully transfer to other schools or majors each year, and the receiving school is usually ranked lower than the previous one.

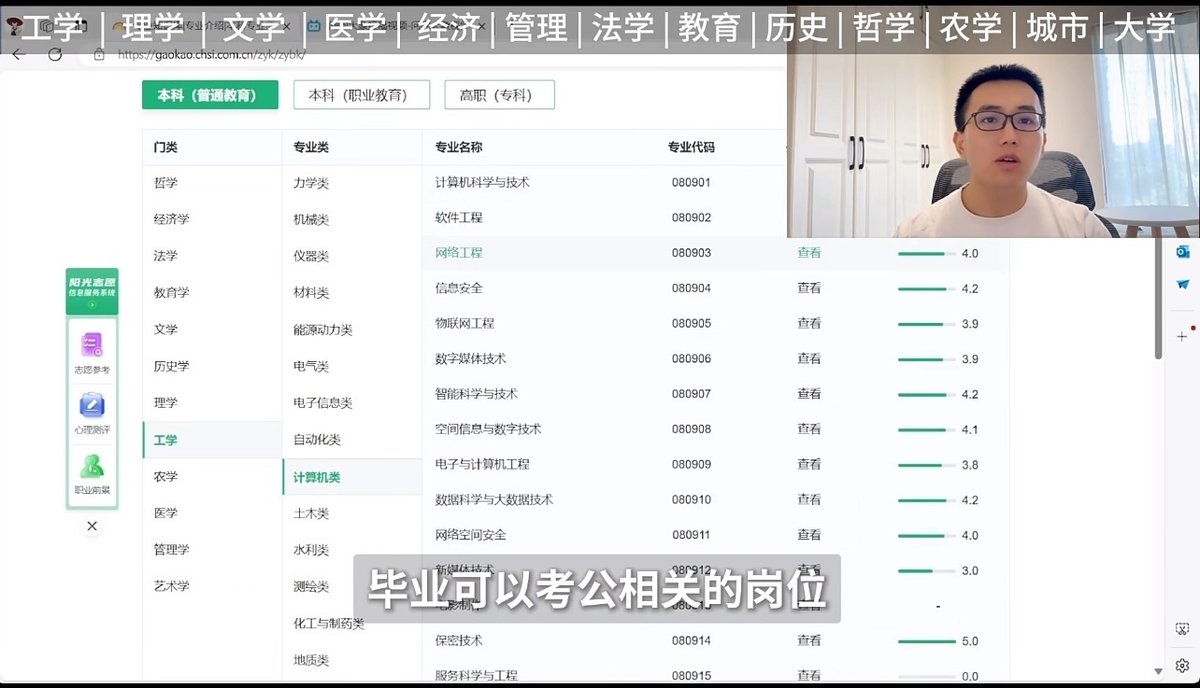

The sheer amount of information available nowadays also presents a unique obstacle. The Chinese mainland boasts over 3,000 higher education institutions as of 2024, each with varying admission scores for different majors or programs depending on the student’s home province. The application rules for different provinces can also be confusing. For example, there is the concept of parallel major categories and parallel majors within the same category. A student can apply for multiple parallel major categories at the same university. Within each category, they can fill in up to six parallel majors. “This type of ambiguous language may easily cause confusion and even mistakes in the subsequent application process,” says Zhang Pengxing, a high school English teacher at Beijing National Day School. There are also new changes in the majors and programs offered by each school every year. As the country pushes for gradual reform to the gaokao system, it can be difficult for those not working in education to keep up.

However, with such high stakes, career education resources provided to students at the high school level are lacking. “Students in China tend to spend three years cramming single-mindedly for a good score but only 30 days or less contemplating which school to attend,” says Jing. Beijing, for example, releases gaokao scores on June 25 this year, and students have six days from June 27 to July 1 to fill out the application. Jing believes that the counseling services now available in the market are a much-needed complement, offering crucial support in making informed decisions about college and future careers.

The booming market

While application counseling is not a new concept in China, as open lectures and paid classes hosted by local schools and educational professionals have always been available to parents and students, the rise of livestreaming and the sluggish job market have given new momentum to the business.

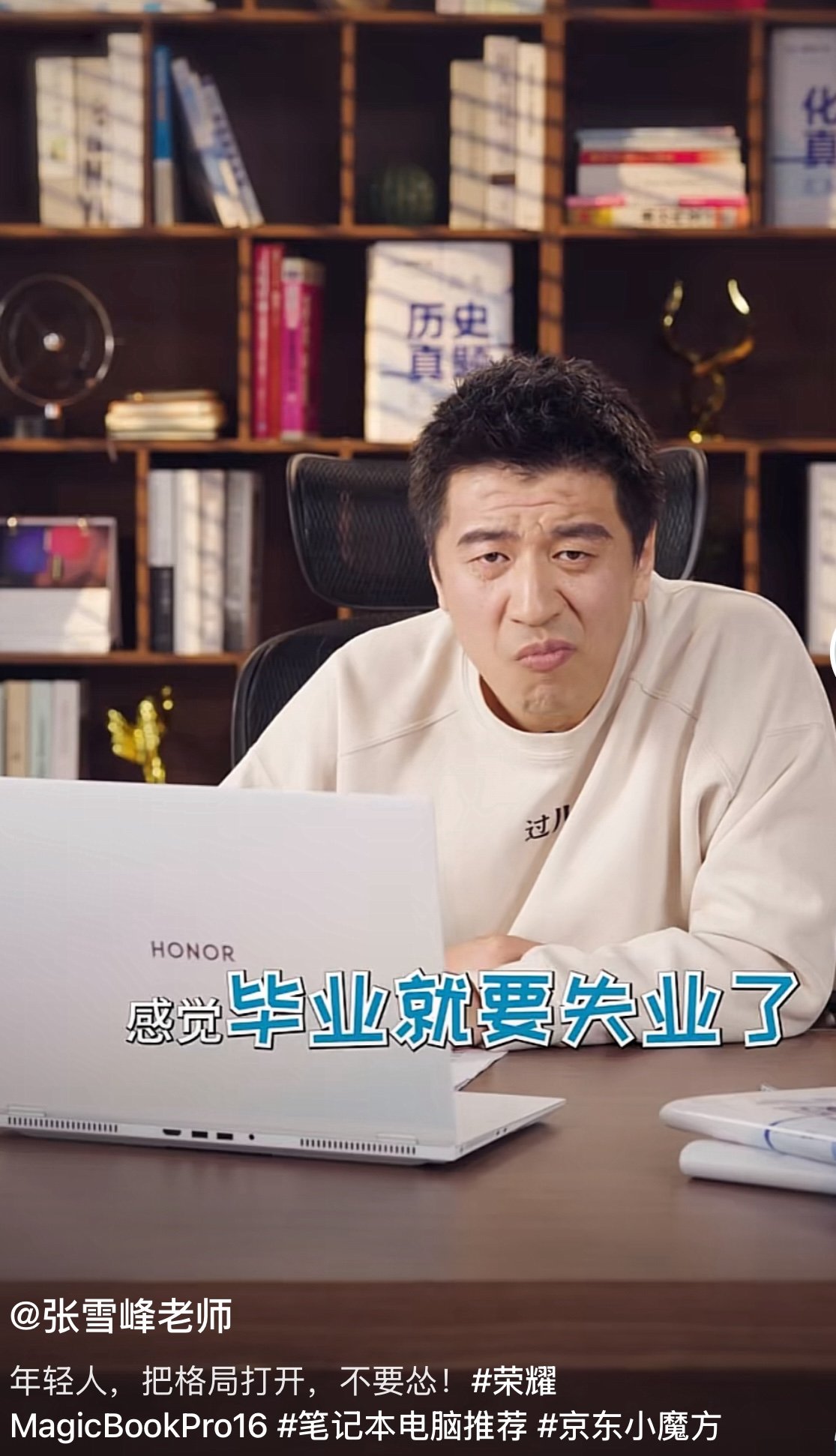

According to iiMedia Research, an economic research platform, the market for paid college application consultation in China was worth 950 million yuan in 2023. Nearly 90 percent of surveyed students expressed their willingness to pay for such services. Information published by business data provider Tianyancha shows that about 80 percent of all 1850 enterprises registered in the area of college application counseling were established within the last five years. Zhang Xuefeng, China’s most popular and controversial education influencer, now charges 17,999 yuan for his personalized one-on-one consultation service. An employee of a consulting agency, identified only by the surname Ren, was recently arrested for spreading rumors on Douyin, China’s version of TikTok, claiming that 190,000 students from Shandong failed to get into their first-choice schools, just to promote his company’s services.

Chinese tech giants, including Alibaba, Baidu, Tencent, and Netease, have also jumped on the trend by creating their own online consultation platforms using AI. Alibaba’s large language model search engine Quark, for instance, offers major recommendations and simulated application forms based on the user’s score and ranking in a particular province. This June, Alibaba unveiled Quark Gaokao, an information service app that can narrow a student’s choice down from more than 3000 colleges and universities to a little over a dozen. These services are typically offered at a relatively modest price of several hundred yuan.

Jing started his own consultation business last year after quitting his job as an educational product manager at Tencent. While working at Tencent, he met many college students who expressed regret at the major they chose because they had no idea what kind of career their choices would entail when they filled out the application. He now offers free online counseling through his channel “Wen Wen Da Xiang (问问大象)” to attract more students to his knowledge-sharing groups on China’s ubiquitous messaging app WeChat, where experienced college students can share their insights and advice with newcomers. His WeChat groups now have around 20,000 active members in total. He hopes to convert these free users into paid members for his college-level counseling service, where he offers advice on job hunting and graduate school applications. The six-month membership fee now stands at 699 yuan. Jing believes it’s a fair price for his target clients, who are mostly from low or middle-income families that lack the necessary social connections and need peer advice and foresight to craft their career plans. He now boasts a paid membership of around 1000 people.

Not a guarantee

While major influencers like Zhang Xuefeng offer personal and practical advice to students and families, most consultancies can’t live up to that bar.

Liu Fang, director of admissions at Beijing Forestry University, finds that most of the services she’s encountered were unprofessional. Some services even missed the latest reforms in application policies and rules in certain provinces. She says that many parents call to ask for their advice each year, and some have paid from 6000 yuan to 50,000 yuan for outside services. In one case, a student’s family paid a shocking 36,000 yuan, only to have the student end up in a major for which he was significantly overqualified, wasting over 100 points between his own score and the admission line.

“The priority of these education agencies is to get the student into a school, any school. They don’t have the interest of students and parents at heart,” says Liu.

When Song, now a sophomore finance major at Donghua University in Shanghai who only gave his surname, was filling out his application in 2022, his father paid 3000 yuan for a premium package from the Shandong-based consultancy company Daweilai (大未来). However, the agency only provided very general information about majors related to Song’s interest in economics, and at one point even advised him to pursue education and Chinese linguistics, majors that typically lead to traditional “iron rice bowl” jobs like teaching and public service. Song eventually made his own decision and went for a degree in finance, a popular major in recent decades.

However, once Song began his studies, he quickly realized that the agency had also failed to explain what a major in finance entails and how it translates into the job market. He found that the finance courses weren’t very in-depth and primarily served as an introduction to a career in academia rather than preparing students for jobs in the real world. “Do you need to study economic theory to work as a bank teller or in insurance sales? No, you don’t,” says Song, referring to the entry-level jobs most finance fresh graduates might land. He also learned that high-paying jobs, such as financial analysis and risk management, are often exclusive to students from China’s top nine schools, known as the C9 League (九校联盟), or those with family connections in the industry.

“The so-called popular and prospective majors might not suit everyone,” echoes Fan Tingting, associate professor of Japanese at the Beijing Forestry University. In the past two years, her class has seen five students transfer from popular majors such as landscape architecture and soil and water conservation. “These students either found out that they were not interested in the subject, which their parents decided for them, or weren’t as good at it as they expected, leading to a chain of frustration and thwarted confidence,” says Fan.

A well-informed, yet personal decision

Liu, the admissions director, believes that instead of putting their faith in strangers’ advice, parents and students can find more reliable information from open data available on the official channels. This year, the Ministry of Education launched Yangguang Gaokao, a free information service that offers official interpretations of the admission policies, past information on the admission lines, major recommendations, and employment satisfaction based on alumni ratings. The enrollment brochures and catalogs of majors can be found on the official website of the corresponding university.

Zhang, the Beijing high school teacher, says his school now provides students with one-on-one consultations with headteachers of their applying classes, who know the students well and are familiar with the application process. Throughout the year, the school also invites top practitioners from each industry to communicate with the students. “This way the students will know what the industry is actually doing and better craft their career plans,” says Zhang.

Many universities have also loosened their requirements for switching majors in recent years. For instance, Beijing Forestry University introduced a “zero-threshold” policy for in 2023, allowing students to apply to switch majors in their second, third, and fourth academic semesters.

Local governments are devising new ways to ease college application processes and boost youth employment. In March this year, the Youth League of Sichuan province launched the “Partners for the Future” project, which collaborates with educational influencers like Jing to provide information on college applications, campus life, and recruitment prospects.

Ultimately, Fan, the Japanese professor, cautions parents not to make a decision against their children’s will. Her daughter went to college last year to study calligraphy at the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute. Though many might think her daughter could have aimed for a more potentially lucrative major, Fan believes in her daughter’s decision. “There are more important things to consider, such as the children’s interests, sense of value, and fulfillment in life,” says Fan.