Wen Ting, the great-granddaughter of Republican Era-poet Wen Yiduo, talks about her great-grandfather’s cultural and emotional legacy

As far as poets go, Wen Yiduo (闻一多) is a household name in China, a “martyr of the revolution” who was assassinated, allegedly by Kuomintang agents, on July 15, 1946. His works about a new country on the rise—set in opposition to a ruling system he saw as stagnant and rotten—captured the fervor of the era, and won supporters far and wide.

Wen was a leader of the China Democratic League, a minor political party. He wrote fiercely about societal ills, but his poetry is mostly free of overt politicization, and can be appreciated on its own terms, divorced from the bloody infighting of the period.

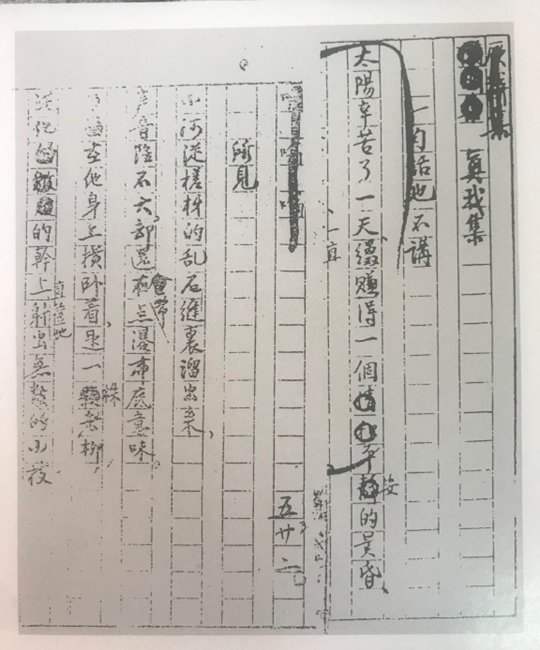

It’s only a pity that outsiders don’t know much about him. Despite an English publication of his poetry in 2014—Stagnant Water and Other Poems, translated by Robert Hammond Dorsett—Wen has remained obscure to international readers. Partly this is because he died young—at age 46—and partly because he only published two full-length collections (Red Candle in 1923, Stagnant Water in 1928). But it may also be because his death—gunned down outside the office of the Democratic Weekly after giving a rousing speech denouncing the ruling Kuomintang—has overshadowed his status as a poet. “I think that currently, when promoting Chinese figures, especially of their generation, we tend to see them as revolutionary martyrs,” said Wen Yiduo’s great-granddaughter, Wen Ting, who is currently a professor at Beijing Language and Culture University. “However, when looking at my great-grandfather, I actually see a fusion of Chinese and Western cultures, as well as an integration of ancient and modern cultures, which is very profound.”

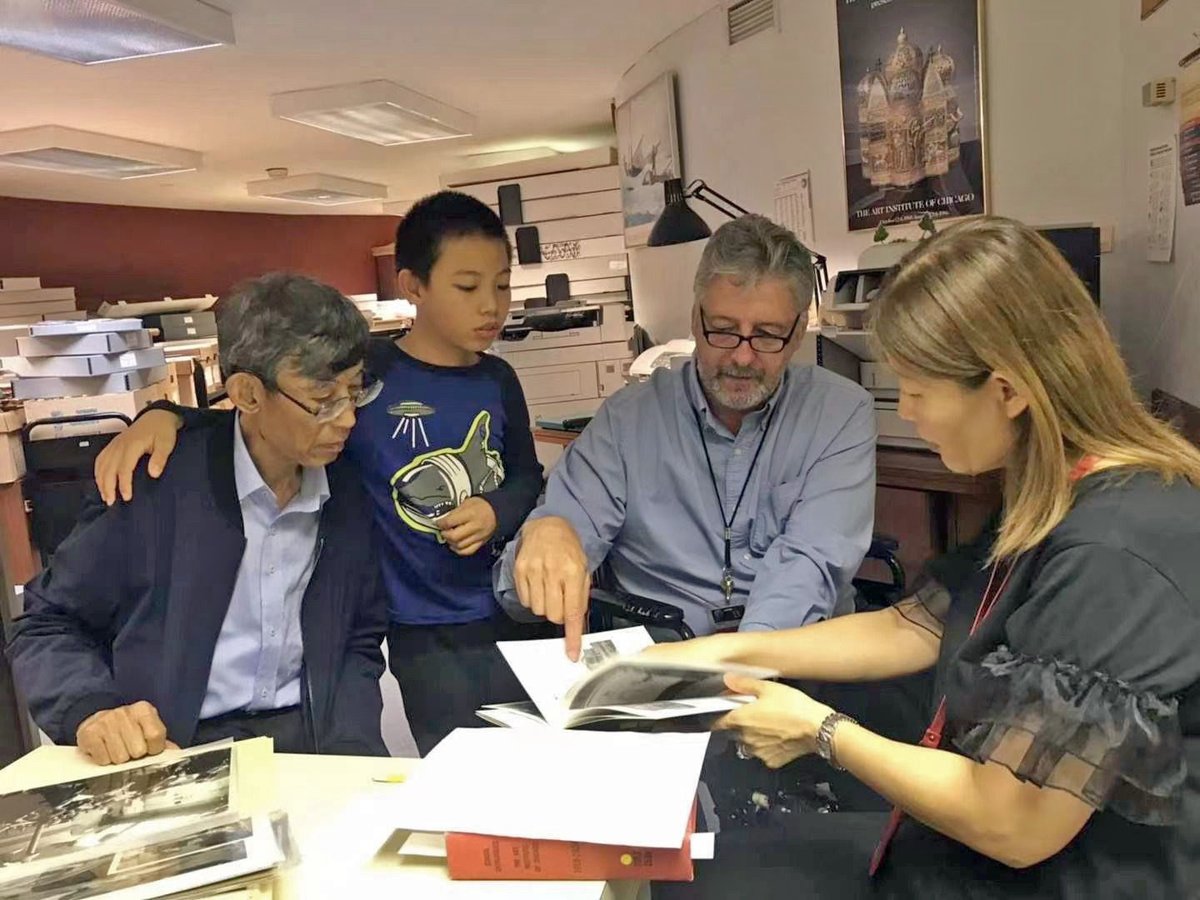

Wen Ting’s father, Wen Liming, researched Wen Yiduo extensively while working at the Institute of Modern History of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. In 2019, at the age of 39, Wen Ting decided to join her father in learning more about Wen Yiduo. Working at Columbia University in New York at the time, she decided she would follow in Wen Yiduo’s footsteps, and retrace his time living and studying in America almost one century earlier.

We recently interviewed Wen Ting to learn more about her great-grandfather, the legendary Wen Yiduo.

Learn more about China’s historical figures during the Republican Era

- Reclaiming the Genius of China’s First Female Architect

- How a Patriotic Organization Evolved Into a Martial Arts Icon

- The Great Educator

Wen Yiduo studied in Chicago, Colorado, and New York from 1922 to 1925. Why did you decide to explore his time in the US?

Previous generations of our family did not completely walk the path he walked. Personally, I feel that this was a process of pursuing truth. For me, as a scholar, every field has its pursuit of truth and reality. So, being physically there meant we obtained some of the most precious firsthand information and facts. I think this is the most important thing to do when studying a person. At least from a research perspective, the most important thing is to go to an archive, not just a library.

What were the most interesting stories you uncovered?

One of Wen’s good friends, Liang Shiqiu (梁实秋, a writer, translator, and literary critic), sent him a letter with some small postcards from Colorado, asking Wen, “How does it compare to Chicago?” Chicago is an industrial city, while Colorado at the time was actually a relatively rural place. Wen took a small suitcase and went there in 1923. He didn’t tell Liang. When he arrived, he surprised his friend. I feel like Wen is someone who is very spontaneous, willing to be with the people he likes.

Another thing that was very interesting, when we were in Colorado, we kept looking for his enrollment and academic records, but we could never find them. Why not? Turns out, Wen didn’t get his diploma because he didn’t want to study mathematics. He said he didn’t want to study something he didn’t like just to get a diploma, so he didn’t take math, even though it was a required course. As a result, he didn’t get his diploma [from Colorado College].

Can you tell us more about his life as an art student?

Wen was the first person from Tsinghua University to go abroad to study Western art. At that time, studying art might not necessarily guarantee good job prospects, but he still chose to do it.

Wen didn’t complete his studies in the United States. At that time, he had greater calling—to save his country and survive. He was acting in dramas with the renowned female writer Bing Xin (冰心) at that time. He felt that drama was a way to save the country, so he resolutely returned to his country.

He returned with the dream of saving the country with drama, but this dream was not realized due to various issues. In any case, he chose this path and considered himself part of a proud lineage of poets and artists.

Did you know that there are translated works of Wen’s poems in the West?

I didn’t know there were English translations of his poetry collection. But when I was in the United States, I discovered that someone had turned his poems into piano pieces.

Why do you want to share these stories about Wen with your students?

We should be able to see that he is an emotional person of flesh and blood, not just a democratic fighter. This was my thought at the time. Every time I’ve spoken, audiences have given positive feedback and said they didn’t expect to hear such a story.

What do you think Wen Yiduo’s stories or experiences can teach us?

When each of us is thinking about our own path for future development, we should consider how we can contribute to our country.

When the country was very poor, someone invited my great-grandfather to go to the United States, and the whole family started packing. However, my great-grandfather said he couldn’t leave during this time of national crisis. I think patriotism runs in the family.

I think combining the concept of the country with the goals they want to pursue is something that young people should consider when they plan their own lives.

Do you feel like Wen Yiduo deserves more international recognition?

Because his poetry reflects the era in which he lived, it’s very difficult to understand all of his works, even for someone close to him like me. Of course, as a relative, I would hope that our loved one is recognized by people from all over the world. But I think it’s not necessary to push for it. When society needs his voice to be heard, his works will find their audience.

Images courtesy of Wen Ting