The bestowing of red pennants, or “jinqi,” has evolved from a simple acknowledgment of appreciation to a token for career advancement and even a means to subvert authority

When the British rock band Suede rolled into the Shanghai Stadium on June 1 to prepare for their concert, they were met with a red velvet pennant with golden tassels hanging by an ironing board backstage. On the fabric, gleaming golden letters in both Chinese and English read, “Sending our deepest love to Suede. We all become the beautiful ones in each other’s life. From all your fans in China.”

Receiving such a gift from fans for the first time, Suede’s bass player Mat Osman tweeted, “I decree that all Suede backstages from now on should contain…a Champions League style personalized pennant.”

What Osman didn’t realize, is that the longstanding Chinese tradition of gifting pennants, or jinqi (锦旗), has little to do with sport (despite their aesthetic similarities to soccer crests often exchanged between teams before matches). Instead, pennants, always featuring gold characters on red velvet, are symbols of honor and respect with ancient roots, and were once reserved for soldiers and doctors.

In ancient China, generals used comparable flags to command armies thanks to their distinctive colors and markings being visible from afar. Killing the enemy’s top general and capturing their command flag was the greatest honor for a warrior in ancient warfare, and commanders would similarly reward their soldiers with decorated flags for feats of bravery on the battlefield.

However, during the Song dynasty (960 – 1279), society favored refined intellectuals over battle-hardened generals. The Song emperors began to reward scholars who excelled on the imperial exams with jinqi. In his poetry, Song dynasty scholar Li Maoying (李昴英) described how people who passed the provincial round of the imperial exam celebrated by hanging a jinqi at their front gate. Since then, these pennants have become a symbol of recognition for people’s achievements.

Learn more about how traditional Chinese culture is adapting to the present:

- How Baijiu Reinvented Itself for Chinese Youth

- How China’s Declining Marriage Rate Soured the Candy Industry

- Tea Total: Is China’s New Social Media-Fueled Tea Craze More Than Just a Fad?

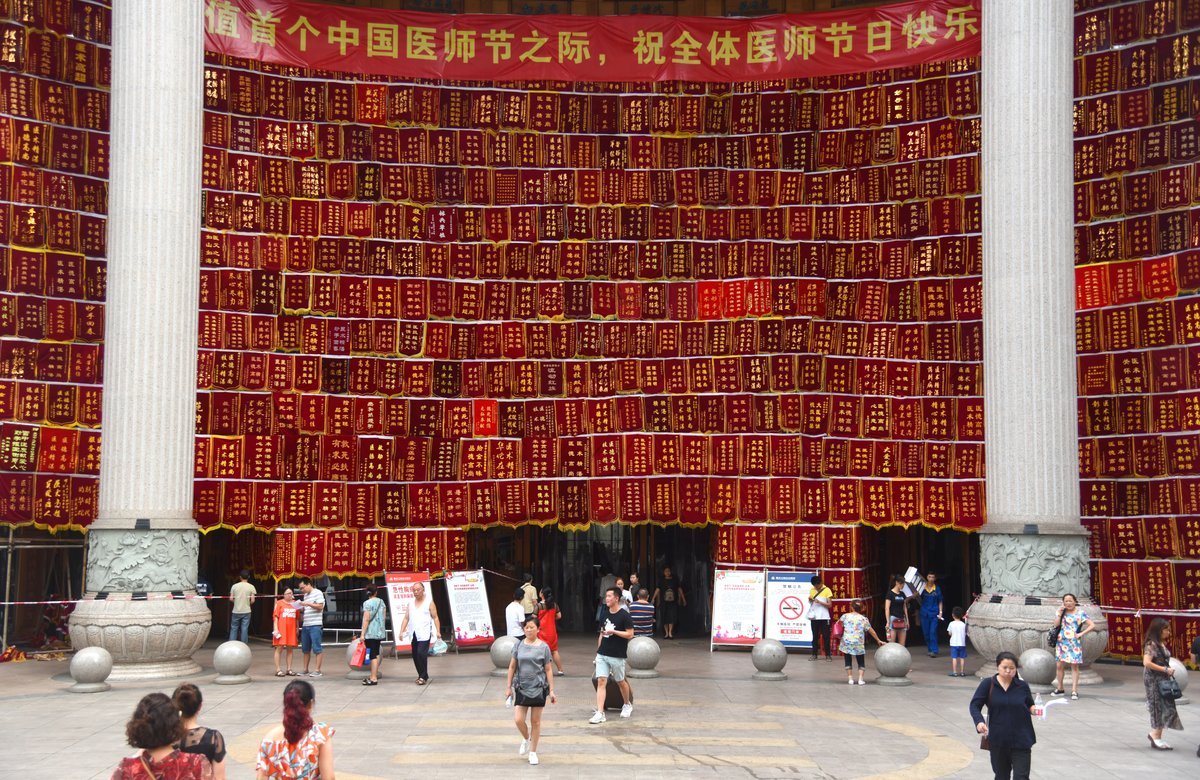

Nowadays, walls adorned with jinqi from patients praising doctors for their surgical prowess are a common sight in Chinese hospitals. Such displays are also increasingly seen in police stations, schools, and even veterinary clinics.

“While there are many other common ways to express gratitude, like writing thank you letters or giving gifts and red envelopes, only pennants appear noble and also comply with legal, ethical, and cultural norms and customs,” Dr. Cai Minkun wrote in the academic journal Medicine & Philosophy in 2021, referencing tightening regulations against conspicuous gift giving and perceived bribery in the medical field. Cai noted one potential pitfall when writing thank-you letters: “Fear on the part of the donor that the language used may be of improper, insufficient, or inadequate expression.” The contents of most traditional jinqi, on the other hand, are derived from tried-and-true templates that are always appropriate.

This rigid nomenclature makes jinqi well suited for showing appreciation to those in China’s more staid positions, such as civil servants, public officials, and employees of state-owned enterprises. “Their leaders will notice their hard work when we gift them pennants. It can enhance their performance assessments and sometimes even lead to them winning annual outstanding employee awards,” Tina Cao, who presented a pennant to a bank clerk in Hunan province this February, explains to TWOC. After seeing the extra care the employee had put into patiently helping her make an urgent wire transfer, Cao noted her name and immediately ordered a customized pennant on the e-commerce platform Pinduoduo.

When the 32-year-old showed up at the bank with a pennant in hand a week after her initial appointment, the employee and her boss were called. “It is a form of recognition for the leaders, too, because they nurtured the subordinates,” Cao says, adding that she hopes it may result in a bonus for the staffer at her year-end review. Holding the bright red pennant reading “Dedicated Service, Caring for Customers,” the three of them took a photo together. The employee was thrilled to receive her first jinqi, and Cao later detailed the experience on the social media platform Xiaohongshu.

Similarly, many others have taken to social media to share tactics for the best way to deliver a jinqi, expressing a wish to increase the likelihood of career advancement among their recipients. A quick search on Xiaohongshu reveals more than 600 posts about “jinqi-giving procedures,” with most advising the bestower to loudly announce their presence and even pretend to be lost so that everyone knows who they’re looking for. “Remember to never put a date on the jinqi so that doctors can reuse them for future performance evaluations,” advises one medical student on the platform, referring to how doctors commonly record how many jinqi they receive in a year to demonstrate favorable performance to their superiors.

The popularity of jinqi may also be attributed to their modest prices. “It’s cheaper than a couple of milk teas,” says Cao. She bought her pennant for less than 30 yuan. A search on the e-commerce platform Taobao reveals even high-end jinqi, sometimes featuring hand-stitched embroidery, cost less than 300 yuan.

However, low prices don’t necessarily mean small profits for jinqi businesses. For the past 20 years, Zhang, a pennant manufacturer from Shandong province who only gave his surname, has made a good living from selling jinqi. Starting as a small storefront offering various printing services in the provincial capital Jinan, Zhang’s store now solely focuses on making jinqi and selling them nationwide on e-commerce platforms. “The sales have remained steady over the years, regardless of economic upturns or slowdowns, because we’re in a niche industry,” Zhang tells TWOC.

What people write on jinqi has also evolved over the years, especially now that younger generations are adopting the trend. While the standard stock phrases for appreciation, like the one chosen by Cao, remain popular, creative designs have also started to emerge. “The content has become more colloquial. Instead of neat alignment and rhyming, many reference internet memes or slang. Sometimes it’s just one word,” Zhang tells TWOC. A viral video posted by state media outlet People.cn in 2023 shows a young patient born in the 2000s presenting her ophthalmologist with a pennant adorned with a single number six—internet slang for “awesome.” The doctor, sporting a broad but slightly awkward smile, accepted the pennant, clearly amused by its unconventional content.

Zhang has also seen the usage of jinqi extending beyond expressing appreciation. “Many customers are even ordering jinqi to celebrate their birthdays now,” he says. But perhaps the most unusual request Zhang has received came from a parent: Instead of the usual words of gratitude, the pennant read, “[The teacher is] good at nothing but collecting payment.” The slogan was likely inspired by an incident in 2020 in which residents of a residential compound in Zhejiang province gave a jinqi with the same text to their property management company to protest overpriced parking spaces. The company eventually vacated their post after the pennant went viral online.

While some traditionalists worry that impolite or casual language could tarnish these pennant’s noble traditions, others say it reflects a broader societal trend of young people using sarcasm to express dissatisfaction and frustration at their inability to change the status quo. “If you hang a banner with insulting language in front of a company, they may call the police on you for disrupting their normal operations. But gifting a banner with sarcastic text takes the risk of administrative action into consideration,” says Cao, explaining how a cleverly worded jinqi can become a form of protest.

Regardless of the language embroidered on them, jinqi are unlikely to go out of fashion soon. Zhang isn’t worried about the future of his pennant business. After all, “there will always be good deeds and good people that need to be recognized,” says Zhang.