A history of Chinese marriage ads, from newspaper columns to matchmaking TV shows and mobile dating apps

In ancient China, marriage was more about matching families than love. The principle is summarized by the folk saying, “at the parents’ command, at the matchmaker’s word (父母之命,媒妁之言).” Choosing a spouse based on personal preference was almost unheard of.

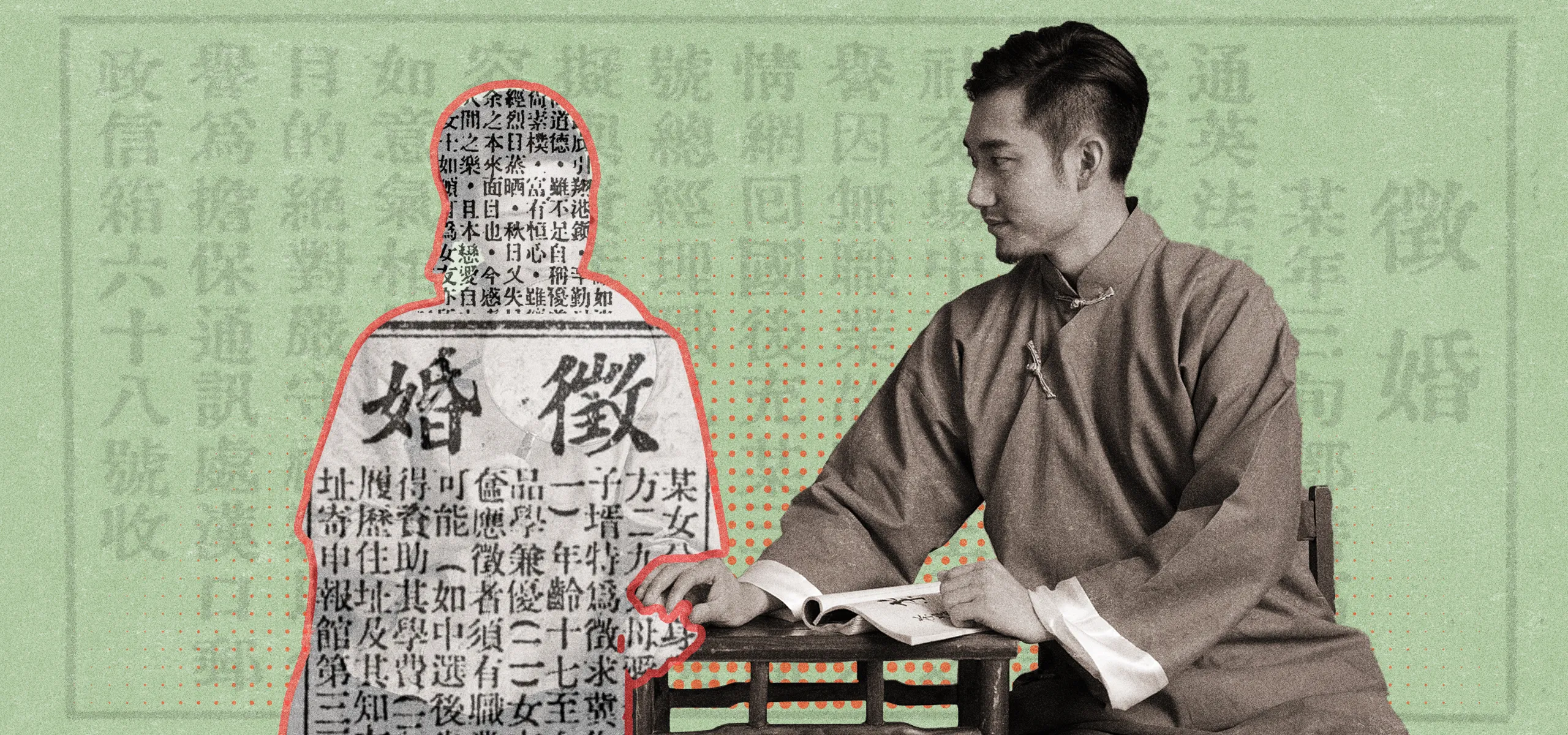

But by the turn of the 20th century, young people began gaining a say in who they would spend their lives with. Thus, a modern way of finding a partner emerged—the matrimonial advertisement, or zhenghun guanggao (征婚广告).

The first matrimonial advertisement in China was published on June 26, 1902, in the Ta Kung Pao newspaper. A man who identified himself as “A patriot from the South” publicly sought a marriage partner and set forth three requirements for his other half: “First, she must have natural feet [foot-binding was still prevalent at the time]. Second, she must be proficient in both Chinese and Western academic disciplines. Third, the wedding ceremony should follow civilized customs, completely eliminating outdated Chinese practices.” The enigmatic suitor added, “Anyone who meets all the aforementioned criteria, is willing to marry of her own volition, and possesses full autonomy is acceptable, whether Manchu or Han, traditional or modern in ideology, rich or poor, noble or common, young or old, beautiful or plain.”

The Southern Patriot’s ad elicited two opposing responses: The Universal Gazette, a newspaper launched by Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911) reformers in 1898, reprinted the advertisement, calling it “the most civilized marriage proposal in the world.” However, Lin Zongsu (林宗素), a prominent feminist at the time, criticized the latent chauvinism in the ad, which highlighted only requirements for the female partner while providing no information on the author. Ta Kung Pao never followed up, so we do not know if the Southern Patriot ever found his ideal partner.

Seeking to further shed light on changing marriage practices in 20th-century China, an article published in the academic journal Encyclopedic Knowledge in January 2024 collected and analyzed matrimonial advertisements from Ta Kung Pao between 1920 and 1939. Author Gao Yating found that of the 80 advertisements placed during this time, 80 percent were penned by men. They also found that marriage advertisements primarily set requirements for partners based on age, wealth, occupation, and education. Male advertisers emphasized age requirements more than females—out of the 64 male applicants, 48 made age a criterion for selecting a partner. Women prioritized financial stability or occupation, with 15 out of the 16 female advertisers stating such expectations. Male advertisers were also more apt to highlight their occupation and financial status, while female advertisers focused more on their virtues, appearance, and household management skills.

“During this period, traditional concepts of marriage were no less influential than modern perspectives,” wrote Gao. “Women were persistently relegated to a subordinate position in gender relations.”

Learn more about modern marriage in China:

- Before Forever: The Rise of Prenuptial Agreements in China

- How China’s Declining Marriage Rate Soured the Candy Industry

- Introducing China’s Marriage Markets

The first matrimonial advertisement placed by a woman appeared in 1922. It was published in the Republican Daily News, a Shanghai newspaper that later became the official newspaper of the ruling Kuomintang party. The advertisement was written in the form of a lengthy poem by a 21-year-old sex worker from Hong Kong named Huang Xuehua. She recounted her tragic experiences of being forced into sex work and expressed her hope for a man to come forward and redeem her. Like the Southern Patriot, it wasn’t reported whether she was successful in her search.

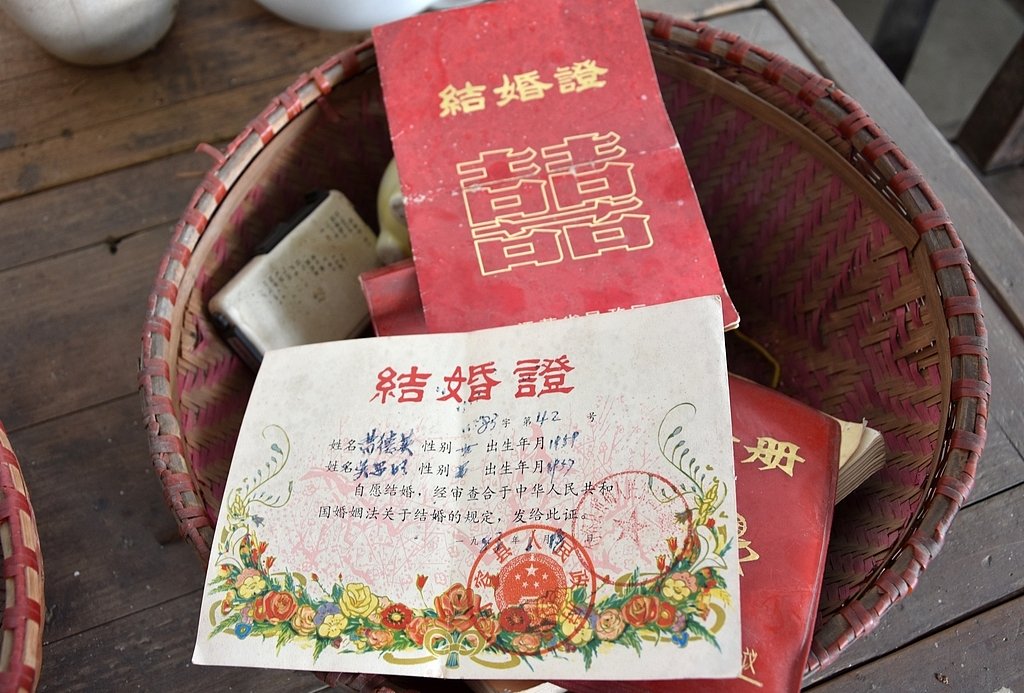

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, matrimonial advertisements disappeared for over three decades. During this time, all private publishing houses, newspapers, and broadcasting stations were brought under state ownership, and their main function was not to disseminate news or advertising but to promote the Communist Party of China’s principles and policies. It wasn’t until 1979 that Chinese newspapers again started to publish ads.

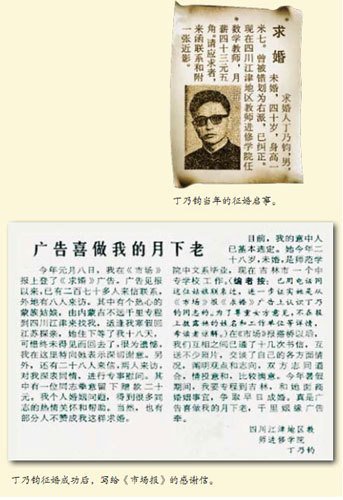

The return of a market-based economy in the late ’70s seemed to mark a renaissance in market-based marriages. In 1981, Market News, a publication established in 1979 under the Party-run People’s Daily mainly providing market and business information, published a matrimonial ad at the request of a 40-year-old math teacher named Ding Naijun. In a long letter to the editors, Ding described how he’d been labeled a “rightist” during the Anti-Rightist Campaign that began in 1959. Though he had been rehabilitated, he still couldn’t find a partner due to the stigma surrounding such ideological pejorative.

This letter posed a challenge for the newspaper editors at that time. There was no precedent for publishing a marriage ad since 1949, and the previous accusations against Ding were still a political concern. Finally, editor Zhao Likun decided to publish the advertisement on page seven of the newspaper, in only 79 words: “Proposer Ding Naijun, male, unmarried, 40 years old, height one-meter-seven. He was wrongly labeled as a rightist, and this has been corrected. Now, he is a math teacher at the Teacher Training College in Jiangjin District, Sichuan, with a monthly salary of 43.5 yuan.”

The advertisement, reprinted by newspapers across the country, divided opinions. Conservative factions argued that Ding had contaminated the socialist ethos, while supporters believed the ad was a powerful testament to China’s reform policies. In 2009, Zhao told the Liaoshen Evening News, a local newspaper in Liaoning province: “I truly felt that I was acting on behalf of the people, and even if it caused [political] trouble, it was worth it.”

The ad brought similar gratification to Ding. Within half a month, he had received over 270 letters from all over the country. He eventually married one of the respondents, a nursing school teacher from Jilin province. Ding notified Market News’ editors of the good news via a follow-up letter, which they also published. After seeing Ding’s success, so many people wrote in with their own ads that the newspaper started a column dedicated to them called “Marriage Proposals.” And as more and more newspapers followed their example, resistance to this modern form of courting gradually subsided.

Several years later, personal ads made it to TV. In 1988, Shanxi Television launched the first mainland Chinese dating show, Telematchmaker, which was marketed as a public service to help rural bachelors struggling to find wives. The format was simple and decidedly unromantic: The guests simply stood in front of a camera and introduced themselves.

It was a struggle to convince the public to do something as brazen as seeking companionship on television. Showrunner Li Zhonglian later told the Shanxi Evening News in 2010 that the station spent three months promoting the show before they attracted their first guest, a man. Meanwhile, the first female guest wouldn’t sign on until many episodes later. When her episode aired, her family condemned her for shaming herself on TV.

According to Li, many people who went on the show were from the margins of society—struggling financially, widowed, or living in remote areas—and hence sidelined in the increasingly competitive marriage market. When the candidates found a partner through the program, they often sent gifts to the TV station out of gratitude. However, the show was canceled after some participants were found to have provided false information, and because fewer candidates signed up once the novelty wore off.

However, Telematchmaker sparked a trend. In the 1990s, TV stations around China competed via their own spin on dating shows, often adding elements more commonly seen in entertainment and reality shows. A successful case was Hunan Television’s Rose Dating, which brought together six men and six women to discuss current events and show off talents, such as singing and dancing. Couples who took a liking to each other would leave the stage hand-in-hand.

TV matchmaking saw its second boom in the 2010s, with Jiangsu TV’s If You Are the One. The show, in which 24 female guests stood behind a podium and evaluated male guests as they came onstage one by one, would become a cultural phenomenon. Male guests would be introduced via prerecorded video segments and by answering questions about their values, interests, financial situation, and more. As the program progressed, female guests could opt out by shutting off the light on their podium. If all the lights went out, the male guest would be eliminated.

The dramatic format helped make If You Are the One a hit, and many of its participants became internet celebrities on emerging social media at the time—but not always for the right reasons. In one notorious example, an unemployed male contestant who enjoyed cycling asked 22-year-old female constant Ma Nuo, “Would you like to go out with me on a bicycle?” Ma replied, “I think I’d rather cry in a BMW.”

Ma’s remark became an instant meme, sparking moral panic about the materialistic values of young Chinese. The State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television demanded dating shows rectify their content, and If You Are the One would become much tamer. As a result, its ratings continue to drop, and it never regained its previous level of success.

Despite its obvious flaws, If You Are the One was still groundbreaking. “In the show...the female guests clearly occupy the primary position, holding substantial discursive power,” researcher Hou Yuling concluded in a 2012 essay published in the journal Theory Research. “The use of this discursive power in the program caters to modern women’s pursuit of equality and freedom,” Hou said. “At the same time, different women can offer diverse interpretations and judgments about the same male guest, which firmly captures a large female audience.”

For those who couldn’t make it on TV, the internet became the go-to replacement for matrimonial ads. Dating website Shiji Jiayuan was established in 2003, followed by Baihe and Zhenai in 2005. Fast-forward to today, and there seem to be as many dating apps as suitors.

But offline matchmaking lives on. Many are propagated not by the candidates themselves but by their parents and family. Beijing’s Longtan Park was allegedly the first to host a “matchmaking corner,” in 2004, a place for kin to display their children’s information on A4 sheets of paper in hopes of helping them attract a mate. Such gatherings have since spread across the country to Shanghai’s People’s Park, Hangzhou’s West Lake, and elsewhere. Some specifically cater to middle-aged or older participants (usually divorced or widowed) who are looking for a companion.

Where matchmaking ads are utilized, parents will often display—and expect any potential mate’s parents to provide—their offspring’s housing situation, salary, profession, household registration location, age, appearance, and marital history. In her 2012 book Who Will Marry My Daughter, social scientist Sun Peidong coined the term “silver-haired matchmaking” to describe this trend. In an interview with Shanghai’s Oriental Morning Post, Sun described how “the essence of ‘silver-haired matchmaking’ is that the parents of unmarried men and women seek ideal love for their children in the secular market mechanism.”

However, despite their media exposure, marriage corners don’t seem particularly effective. During a 10-month field study in Shanghai People’s Park, Sun only found one successful case of matchmaking. “Its low success rate fundamentally lies in the fact that people try to solve emotional problems with a market approach,” she told the newspaper.

From newspapers to television to the internet, marriage ads have mirrored, as well as helped to instigate, transformations in China’s dating culture. However, despite the cutting-edge technology now available to lovers in wait, seeking true love does not seem to have become any easier. According to statistics from the Ministry of Civil Affairs, while there were 7.68 million marriages in the country in 2023, a rise for the first time in 10 years, approximately 240 million people remain single either out of their choosing or not. Perhaps, like when the Southern Patriot placed his ad in Ta Kung Pao, we are witnessing yet another revolution in Chinese attitudes toward love and marriage.