Tech-related businesses are encouraging their workers to create an online presence, and encountering many of the pitfalls that fame can bring

When Yu Minhong, CEO of China’s livestreaming sales platform East Buy, made “a modest remark between friends,” he likely did not expect it would cause him such grief. The problems began on May 31, when Zhang Wenzhong, founder of supermarket chain Wumart, asked Yu for sales tips during his debut livestream on the short video platform Douyin (China’s version of TikTok). Yu replied, “East Buy is in disarray, and [I’m] in no place to give you any advice.”

Yu’s flippant, self-deprecating reply saw the company’s stock price plummet by around 22 percent—approximately 4 billion yuan in market value—over the following days. Meanwhile, the hashtag “Yu Minhong said that East Buy is in disarray” received over 68 million views and thousands of comments on the microblogging platform Weibo.

By June 7, Yu had publicly apologized to his clients, stockholders, and investors for his “imprudent expression” via Douyin. East Buy’s stock recovered by nearly 7 percent almost immediately.

Read more about China’s social media trends:

- How China’s Seniors Got Hooked on Short Video Influencers

- The Rise and Fall of China’s OG Social Media Platforms

- High Stakes in Short Takes: China’s Booming Micro-Drama Business

As one of China’s “online celebrity” entrepreneurs with a combined following of over 30 million fans on Douyin and Weibo, Yu is no stranger to media and public attention, as well as the direct effect it can have on his company’s financial performance. Neither is he coy about another downside of fame—online attacks, telling Zhang in the now-infamous May 31 livestream: “Over the past year, I’ve received 100 lifetimes’ worth of abuse, criticism, and insults.”

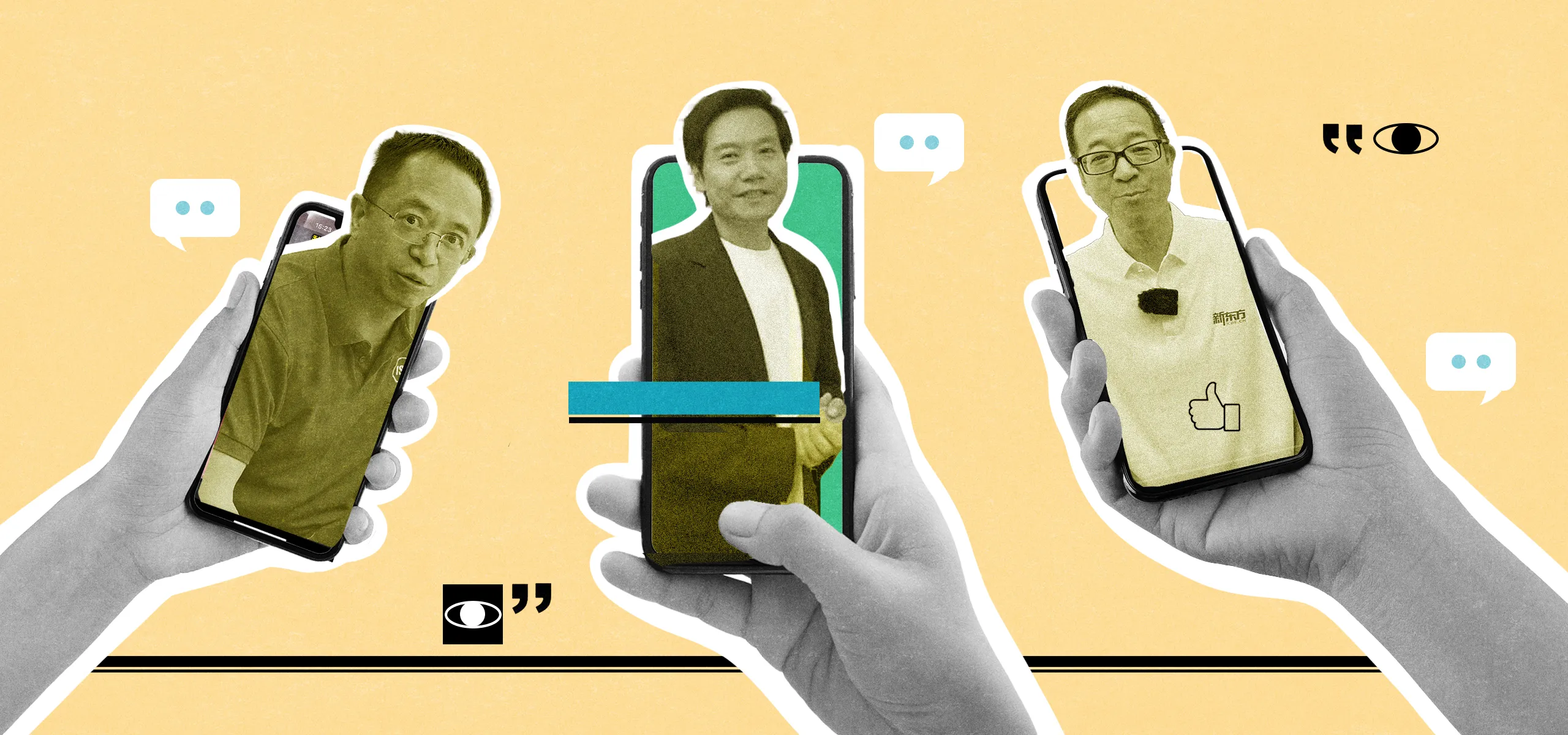

Yu’s experience is illustrative of the pitfalls many of China’s entrepreneurs and executives face as they increasingly turn to social media platforms to boost online traffic and publicity. Furthermore, several prominent employees tasked with garnering attention for their respective companies have recently found themselves out of a job after courting controversy, attracting more attention than they perhaps bargained for.

One advocate for the entrepreneur-turned-influencer model, and who has so far avoided controversy, is Zhou Hongyi, co-founder and CEO of China’s cybersecurity company 360 Group and reported director of 120 companies around the country, according to Chinese business database Qichacha. Zhou, who has been recorded saying, “All entrepreneurs should be online celebrities if possible” during various public speeches and interviews, visited East Buy in January to meet with Yu Minhong and Dong Yuhui (the company’s most popular livestreamer) to learn about the “online celebrity economy.”

Since then, his related Douyin and Weibo accounts have posted several times per day instead of 10 or so times each month previously. Topics are as wide-ranging as vehicle and AI industry developments to social issues like school bullying. “In this world, people’s minds have been ‘reformatted’ by short videos and livestreams, and cannot process information via other means…If a company has no online celebrity, either via its boss or employees, its new products may go unnoticed despite regular launch events,” Zhou explained during a livestream at around the same time as his visit to East Buy.

Zhou’s efforts have been quite fruitful: His followers on Douyin increased by nearly 2 million to a total of more than 5 million in the first quarter of the year. And the 53-year-old—dressed in his typical red polo shirt, casual pants, and a pair of sneakers—was said to have attracted more attention than any of the new cars or scantily clad promotional models at the 2024 Beijing International Automotive Exhibition in April. Crowds followed him throughout the event, and more than 5 million viewers joined his five-hour livestream.

Even a 42-second vlog on Weibo released on April 18 announcing his plan to sell his nine-year-old Maybach received over 7 million views and led to dozens of Chinese carmakers sending their vehicles to his offices to try out. “I cannot fall asleep at night. I’m like a mouse who fell into a rice jar, not knowing which grain to eat first,” Zhou said in a following vlog on April 19, sharing his excitement about the new cars he received.

Despite his newfound fame, Zhou is far from satisfied: “My goal this year is to increase my number of fans [on Douyin] to 10 million,” he told news media The Paper on April 25, adding his ultimate goal is to “promote the company” and “save billions of advertising fees.” These comments echo those made by Xiaomi’s CEO Lei Jun, whose livestreamed presentation at the launch event of the tech giant’s automobile SU7 on March 28 drew over 100 million viewers and is believed to have significantly contributed to the car’s sales, which drew approximately 89,000 deposits within 24 hours of its release.

In similar efforts, but to much less auspicious ends, Qu Jing, then vice president and head of PR at Chinese search giant Baidu, posted four videos on her Douyin account in early May and garnered over 1 million fans within a week. However, the company’s stock price fell by 2.1 percent and lost 6 billion Hong Kong dollars on May 7 after her endorsement of toxic workplace culture in the videos went viral. The content included remarks such as, “An employee wanted to quit after a breakup, and I approved it instantly,” “Why should I consider the employee’s family matters? I’m not her mother-in-law,” and “If you work in public relations, don’t expect to get the Spring Festival holiday and weekends off.”

Amid speculation that Qu had paid someone to build her “personal brand” rather than cultivating it herself, the incident sparked discussion online as to whether a PR head like Qu should be an internet celebrity and what qualified her to become Baidu’s executive and PR manager in the first place. Qu reportedly left Baidu on May 9 following disclosures from former employees that she had previously required all members of the PR department to establish and run their own accounts on short video platforms as part of their day-to-day tasks.

Despite these recent high-profile snafus, discussions about whether company heads should also flirt with social media fame are not new. For example, on the Q&A platform Zhihu, a thread posted in 2016 titled “What are the advantages and risks to CEOs becoming popular online? What kind of CEOs can make good internet celebrities?” has over 300,000 views.

Perhaps taking pity on his contemporaries, Zhou Hongyi shared his three “golden rules” for entrepreneurs in an interview with The Paper this April: When communicating with outside entities, entrepreneurs should check their ego, and never abuse their customers; be honest; and, finally, “If you can’t stand being criticized, don’t speak out. My advice is either don’t pay attention to it, or if you do, just laugh it off.”

Yu Minhong, attempting to temper the fallout from his jibe about the state of East Buy, managed to incorporate all three in his public apology on June 7: “I’m grateful for all the online comments about me, good or bad. Your attention is the driver of my progress.” Whether or not the public truly believes such pandering is ultimately up to them.