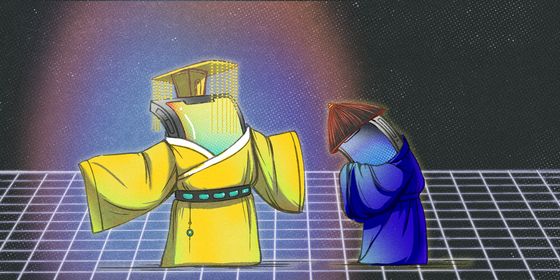

What‘s it like working in China’s micro-drama industry as producers and apps spread the ultrashort format abroad?

Since they first emerged in 2018, China’s micro-dramas (短剧) have become a billion-yuan industry domestically. Now, with tightened regulation and market saturation in China, many companies are taking their minutes-long vertical soap operas abroad.

ReelShort, a Chinese micro-drama streaming app, was downloaded over 7 million times in the US in 2023, and over 24 million times worldwide. Its shows feature scripts adapted from popular Chinese online novels with fast-paced narratives, cheesy rags-to-riches plots, and scandalous love triangles. The format has also attracted the attention of major news outlets.

But what’s it really like working in China’s micro-drama industry? And how are Chinese companies adapting their content for foreign audiences? In this podcast episode, host Aladin Farré talks to two insiders, one actor and one scriptwriter, who work on micro-dramas made in China for audiences abroad. TWOC editor Yang Tingting also discusses her latest in-depth article on micro-dramas and the industry’s working conditions and business models.

Guests:

Anaïs Clément is an actor and theater director who moved to China in 2023.

Jack Li is an actor and director who studied acting at The Central Academy of Drama in Beijing. He also writes English scripts for micro-dramas released internationally.

Yang Tingting is an editor at The World of Chinese Magazine who reported on the domestic micro-drama industry in China.

Subscribe to the Middle Earth Podcast: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Google Podcasts | Amazon Music | Overcast | RSS Feed

The following are excerpts from the transcript of the episode (edited for clarity):

05:01

Aladin: Jack, you’ve been working on micro-drama scripts. Can you explain what type of projects you worked on and the usual themes of those micro-dramas?

Jack: Usually, they come from these websites that have online novels. You buy chapters that you can keep reading. With the data they have, the most popular books get adapted into these short, short dramas and then they outsource writers. Then you write about 70 episodes—a mini-series for them.

Aladin: What are those novels usually about?

Jack: It’s pretty much just Twilight, just a deviation of Twilight. Or a deviation of Fifty Shades of Grey. The main character is usually a werewolf, or a vampire, or a billionaire boyfriend. The girl is a plain Jane who somehow gets swept up by a billionaire who’s also a werewolf, or a billionaire who’s also a vampire. For some odd reason, as she goes through this journey with the guy, who is usually this immature, manipulative person, but somehow loves her, the third person is introduced—another man who has all these great traits. And then they have this love triangle and they struggle between that. By the end, the protagonist needs to make a choice between the two men.

09:26

Aladin: What’s interesting is that the high pace of the storyline is mimicked by the shooting process.

Anaïs: Yes. I was quite impressed. It was not a kind of student movie experience. We had an extremely professional team with minimal material. Two good cameras, two good screens to check, and one or two lights. And that was it. Of course, mics, but it was extremely minimalist yet efficient. We would shoot about 90 episodes. Originally the plan was for eight days, but they had to replan for 10 days.

11:53

Aladin: Tingting, you wrote an article for The World of Chinese, [on the micro-drama industry in China]. After listening to our two guests who are focused more on the international markets, what else did you find in your piece?

Tingting: I think both of you have made great points on the opportunities and challenges in this industry. I also found through my research, that many industry insiders face a lot of stigma, even from themselves. Actors and scriptwriters will face criticism like: you are doing this for money, not for art. And they are accused of producing cheap and brainless content. One producer based in Beijing shared with me that one of the actors he had worked with before even told him to remove his name from the poster because he was afraid that the show would affect his acting career. I don’t know if you guys have the same concerns working in this industry.

13:14

Jack: I think as an actor, yes, it’s a big deal because I’m from the Central Academy of Drama. It sounds crazy, but I wouldn’t do it. Yeah, there is a stigma there, but you have to eat. What I could do is write for it.

Anaïs: No, and for two reasons. First, it didn’t really come to my mind. I was new to China. When I received the script, I read it and I was like, no one is going to watch it. That’s fine. The second thing is that I’m not that recognizable [in the show]. But I also think in the future it could become a real art form but it would take some people from your school and a good writer.

16:49

Aladin: We see that budgets are stretched, and teams are maybe professional in doing things fast, but it doesn’t mean that the quality is going to be high. What is the business model of that? How do the people at the end, like the production company, how do they make money?

Tingting: After finishing this kind of product, they will put them online on platforms like Douyin, Kuaishou, or something else, and then they will charge people to view. But to attract people to pay for the subscription, they will give the first 10 episodes for free. And then if you want to unlock the remaining 90 episodes, you need to pay about 1 yuan per episode, or you can pay around 30 yuan total for the remaining package. You can also watch ads to unlock episodes for free.

Aladin: I was having dinner a few days ago with a friend of mine who is also a scriptwriter. He was explaining the business model is that you would try to convince those kinds of apps for the international market. If they like your script then they would give you half of the budget to shoot and then you would need to find another investor, which is still low. It’s not a lot of money. And then you go on shooting, then you upload on the platform and people will watch you. If a lot of people watch you, then you would maybe start making money.

21:02

Aladin: Unfortunately, across all cultural industries, whether it’s like movies or people trying to be a KOL, at the end of the day, only 5 percent of people make a hit, 10 to 20 percent manage to break even and the rest just lose money. I feel it’s the same ratio again with micro-dramas.

Anaïs: With the difference that in those industries in general, people create an art form that they are proud of. It’s like: “I lost money on this project, but it’s still something that tells something about me.”

Jack: I think it’s the same thing. They’re trying to make it into something legitimate, which they can and they can put more money into it. I’m sure there’s enough audience for that to happen. Even within the art form itself, which is a very niche, erotic, sexual fantasy type of content, they can still make something out of it eventually.

23:09

Aladin: I feel there is a little bit of hype around it. I’m wondering if there is a giant scam to pour money into this whole short video thing because at the end of the day, the platforms don’t have to invest that much and they are the real winners.

Anaïs: From the grassroots, it does feel exploitative for artists and we do it for sports, we do it for money. But, you know, we need to be clear about what it is. It’s not a system that supports artists.

Jack: I think if this industry wants to legitimize it, they would have to put a lot of money into actually bringing in big actors into it just to see if it works. What if somebody just decided to make a big production of it just to see if it’s something that can change the industry? Maybe it’ll happen. I feel like eventually somebody is going to try it.

29:15

Aladin: I do see that C-drama, Chinese dramas, are getting more and more following in Southeast Asia for sure.

Anaïs: Those were created for the Chinese market, so they were genuine stories created by Chinese people, for Chinese people. I think the issue we have with those short series failing in other foreign markets is that they were created with what they think the foreign market wants. They take foreign actors who are not actors, they put them in a set that looks like it’s not in China, but it is. Like one breakfast scene, when the billionaire suddenly got a bowl of noodles. It’s also carrying all sorts of stereotypes that are not always the ones that current society wants to keep carrying, you know, whether it’s gender or race, or money, or social class.

Jack: Catering to the Western market needs a Western eye as well. A lot of these Chinese series that are being AI-generated into North American content or European content, it’s still just skin and bones.

The Middle Earth Podcast is your source of insight into China’s culture industry, where you can hear from people creating and producing content in the world’s second-biggest cultural market. Hosted by Aladin Farré, and presented by The World of Chinese magazine.