How Chinese ID cards evolved from simple handwritten cards in 1984, to sophisticated digital documents essential for everything from riding the train to playing video games

On the evening of August 30, 1984, the Beijing dormitory of China’s Ministry of Culture was buzzing with excitement. In the courtyard, hundreds of residents had gathered to welcome the renowned actor and singer Shan Xiurong. CCTV, the country’s main state-owned broadcaster, and journalists from major newspapers were there to record Shan as she took the stage. But Shan was not about to perform; she was there to collect China’s first ID card.

“The scene of people getting the card was like the Lunar New Year celebrations, with many residents gathered around. Everyone was particularly excited,” Shan recalled in an interview with Beijing Morning Post in 2012.

Shan was handed a resident identity card, or 身份证, a document the government hoped would make it easier to organize society, run public services, and keep tabs on undesirables. Before that day in 1984, people had to carry their household registration (hukou), a flimsy book that lists members of a household and their status as “rural” or “urban,” and an introduction letter from their employer each time they wanted to stay at a hotel or open a bank account. Nowadays, ID cards are used for everything from paying taxes to opening a social media account, using a mobile phone, and entering tourist attractions.

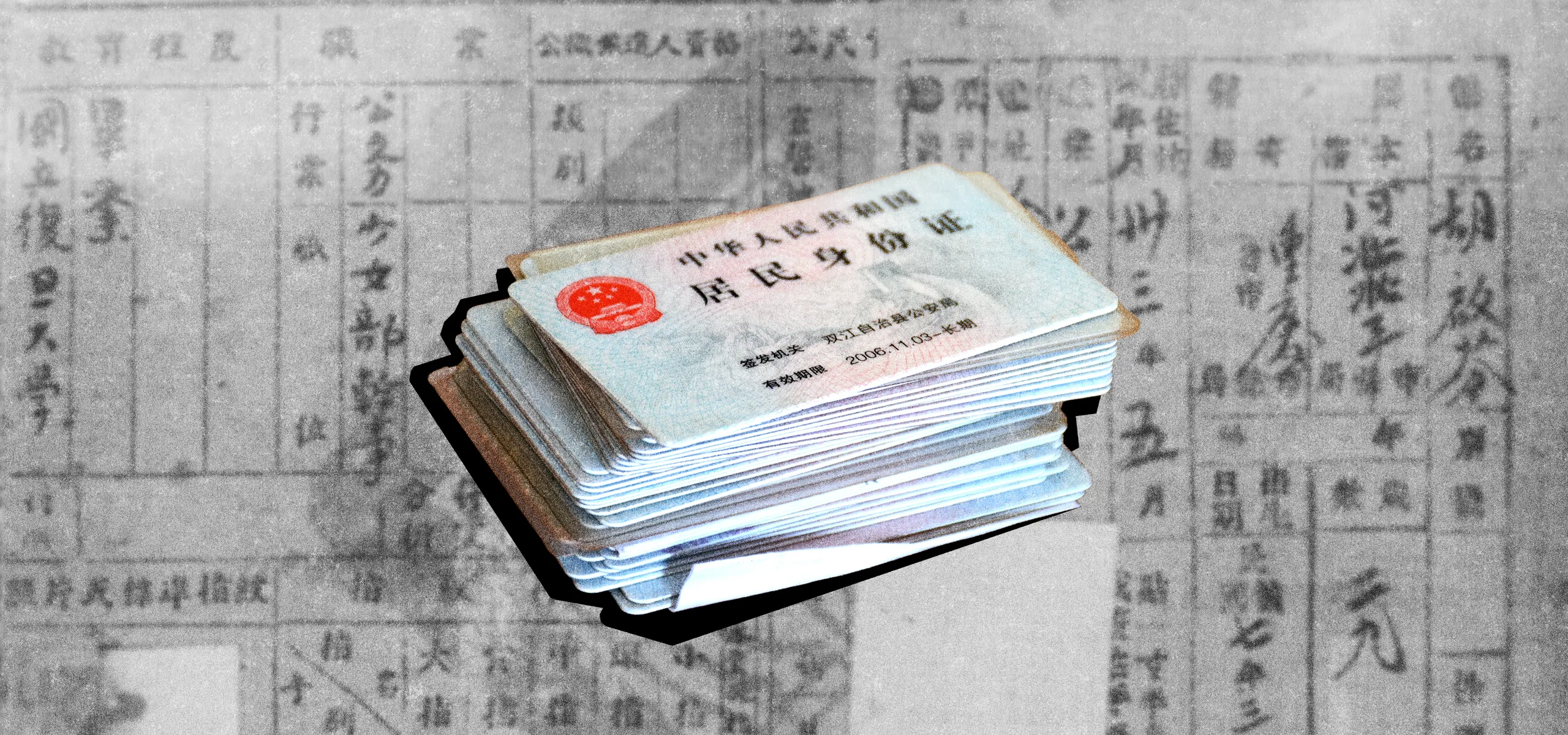

These first ID cards were unsophisticated. They were laminated cards with a black and white photo and hand-written personal information (including the carrier’s name, gender, ethnicity, birthday, and domicile). To keep the cards neat, police stations and local governments sent employees with the best calligraphy skills to help copy the information. According to the Beijing Morning Post, it took five police officers about half a year to make just over 2,000 cards for the Ministry of Culture’s staff. About a fifth of the photos submitted didn’t fit the size or quality requirements.

At least these identifications had photos in 1984. In 350 BCE, China’s earliest identity certificate (known as 照身帖) only included a hand-carved portrait. It was invented by scholar Shang Yang (商鞅) and issued by the Qin government in the Warring States period (475 – 221 BCE). It was a flat bamboo board with the holder’s name, occupation, portrait, and official seal carved on it. Everyone needed one to pass checkpoints on the road or check into guesthouses. In a twist of fate, when Shang Yang later fell out with the Qin authorities and went on the run, he found nowhere to hide because he didn’t dare show his ID to stay at inns on the road.

In the Tang dynasty (618 – 907), a fish-shaped tally (鱼符) was used to identify officials. The small metal fish tally was divided into left and right halves that fit together. One half was left with the imperial court; while the official carried the right half—putting them together could prove their identity. In the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644), a similar system saw officials identify themselves with a small plate of animal bone or ivory (known as a 牙牌) hung at their waist.

By the Republican era (1912 – 1949), identification systems were rolled out to regular citizens, though not nationwide. In Ningxia in 1936, the local government mandated that all residents over the age of 15 must wear a resident ID certificate. By 1940, all men in the region needed to apply for one, and those found without it faced punishment through military service (if they were under 40) or labor. The certificate was a piece of white cloth displaying the person’s name, age, place of origin, occupation, height, description of appearance, and sometimes a fingerprint.

The Nationalist government rolled out a National Identity Card in 1947, but these booklets became mostly irrelevant once the Communist Party came to power in 1949. Before the ID cards of today, however, the new government developed the hukou system in 1958. This registered each citizen to a particular place and defined them as rural or urban. This made it easier to control migration from the countryside to the cities, with regulations fixing people in the areas listed on their hukou. They also introduced a personal record (档案) system that recorded people’s education and employment history.

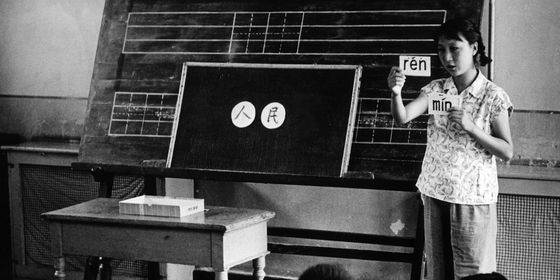

When China embarked on market reforms in 1978, people gained more freedom to move around. But traveling on trains, staying in hotels, or moving job locations meant presenting one’s hukou and an official letter from an employer, making it inconvenient and inefficient for workers to migrate. The first generation of ID cards introduced in 1984 was partly meant to make the labor market more flexible and people’s lives more convenient. The following year they became mandatory for all over the age of 16.

By 1988, no doubt to the relief of police officers with neat handwriting everywhere, the cards were being printed rather than hand-written. But they remained easy to counterfeit, and fraud involving fake or stolen ID cards became worryingly common. In 1999, Beijing Daily reported that a teacher surnamed Wang was hit with a 2,000-yuan phone bill despite not owning a phone. In 2001, a Beijing resident surnamed Liang said she had been inundated with letters from telecommunications companies after someone used her lost ID card to buy 30 mobile phones.

From the 1990s, efforts began to make ID cards, now essential for everyday life and containing sensitive information, more secure. Since 1999, each citizen has been assigned a unique 18-digit citizen number to go with their card. The first six digits reflect the person’s permanent address (linked to their hukou); the following eight are their birth date, and the next three distinguish people with the same location and birthday. The final digit follows a formula to confirm the validity of the ID number.

In 2004, the government launched the second generation of ID cards including digital anti-fraud measures. The cards feature a non-contact IC chip that can be scanned to automatically register information. Today, train stations, airports, and even some residential communities employ facial recognition technologies with ID card scanners to confirm people’s identity.

ID card use has greatly expanded over the four decades since they were introduced. Since 2013, an ID card has been required to purchase phone SIM cards, directly linking people to their mobile phone numbers. China’s 2017 Cybersecurity Law introduced a “real-name verification” system online, mandating internet service providers to request users’ real identity information (by using a phone number linked to their ID card, for example) to surf online.

With so many modern services requiring identification in China, losing one’s ID card is potentially disastrous. Getting a new one is relatively simple—the carrier must report the loss and apply for a new one at their local police station—but since there are few barriers to using a stranger’s card (there is no password linked to them, for example), fraud remains a problem.

In 2010, ifeng.com reported that 19-year-old Lin Beixin was wrongly arrested in Guangzhou, Guangdong province, under suspicion of theft in Yiwu, Zhejiang province. Lin was detained and questioned for 11 days before the police realized Lin’s ID card had been stolen three years ago and was being used by real criminals to hide their identities.

According to the state-run newspaper Legal Daily, millions of ID cards are lost or stolen each year. In 2019, online media outlet Chengdu.cn reported on a 22-year-old woman who received a court summons because a company registered under her name was 2 million yuan in debt, despite her never having heard of the firm. The same year, the People’s Daily reported that the Beijing Municipal Tax Service was investigating a woman surnamed Huang for evading taxes as the legal representative of a company she never registered. In 2020, a woman surnamed Su who tried registering her first marriage was shocked to find that she had already been married in 2014 and subsequently divorced. All these people had previously lost their ID cards.

To fight identity theft, the ID card system began recording fingerprint information in 2013. But cases of fraud continue to crop up. While the Public Security Bureau has a database of ID cards reported lost, one police officer told Xinhua in 2015 that institutions like banks and telecommunications operators don’t have access to it. Stolen cards can, therefore, still easily be reused by criminals.

In fact, now that so much of modern Chinese life is digital and integrated with people’s ID, there may be more risk of fraud than back in 1984 when Shan Xiurong first got her hands on the rough, hand-written card, with much more limited functions.