Since their first appearance in the 1990s, China’s ubiquitous “little ads“ have evolved alongside the cities they serve

When I was a language student in Nanjing 18 years ago, the first two Chinese characters I learned to write were not picked up in the classroom but on the street: 办证. These two characters—literally “handle credentials”—followed by a phone number, seemed to have been written in paint and ink on every wall, pavement, and toilet stall door in the city. As I began to decipher more characters, I sketched in my notebook the full construction: 刻章办证发票.

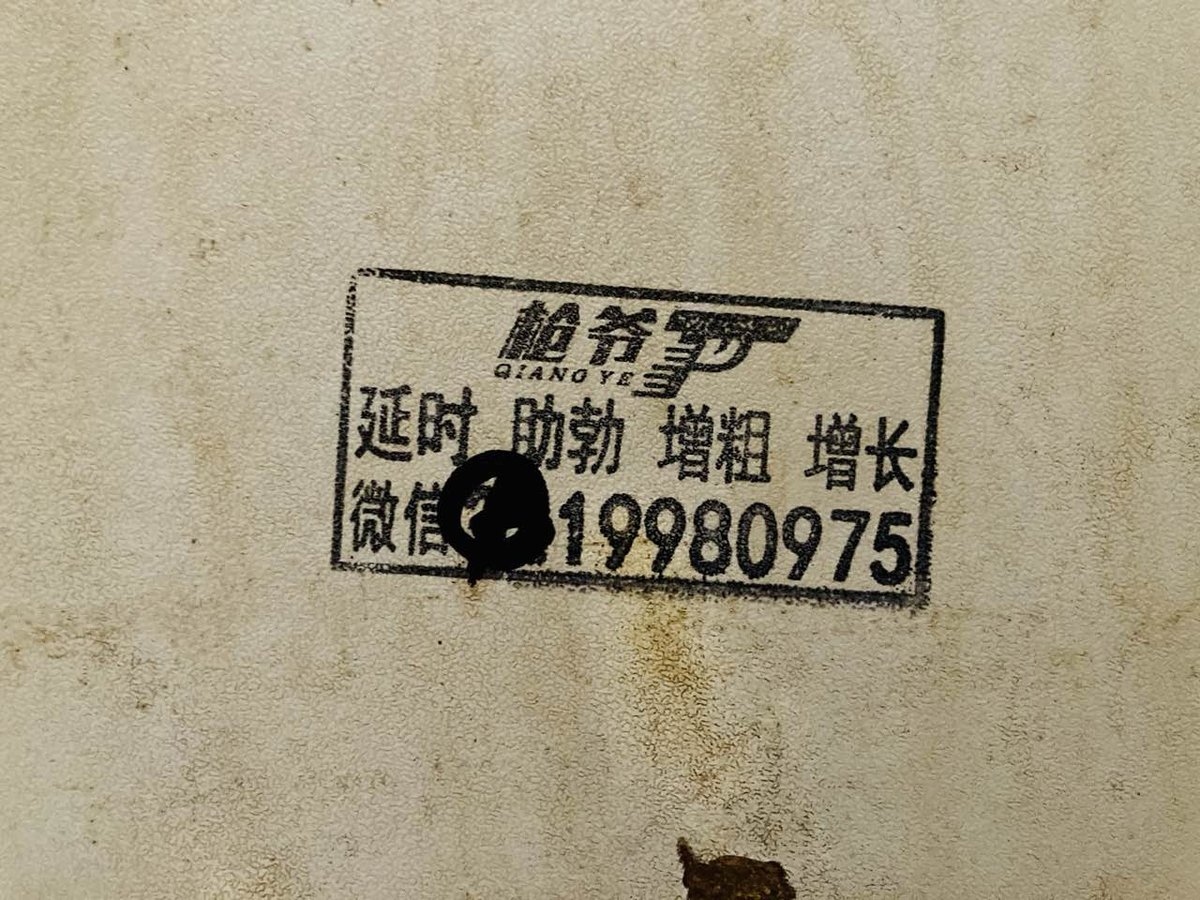

When I finally worked up the nerve to ask a local friend precisely what services these adverts by anonymous entrepreneurs offered, he sniffed derisively. Apart from destroying the harmony of the urban environment, he explained, these vandals were scammers and criminals, offering to put official seals on documents, produce counterfeit certificates, and make fake receipts to be turned over to work unit accountants for reimbursement. Some of the advertisements touted even more taboo products, like commercial sex, air guns, and unapproved herbal impotence cures.

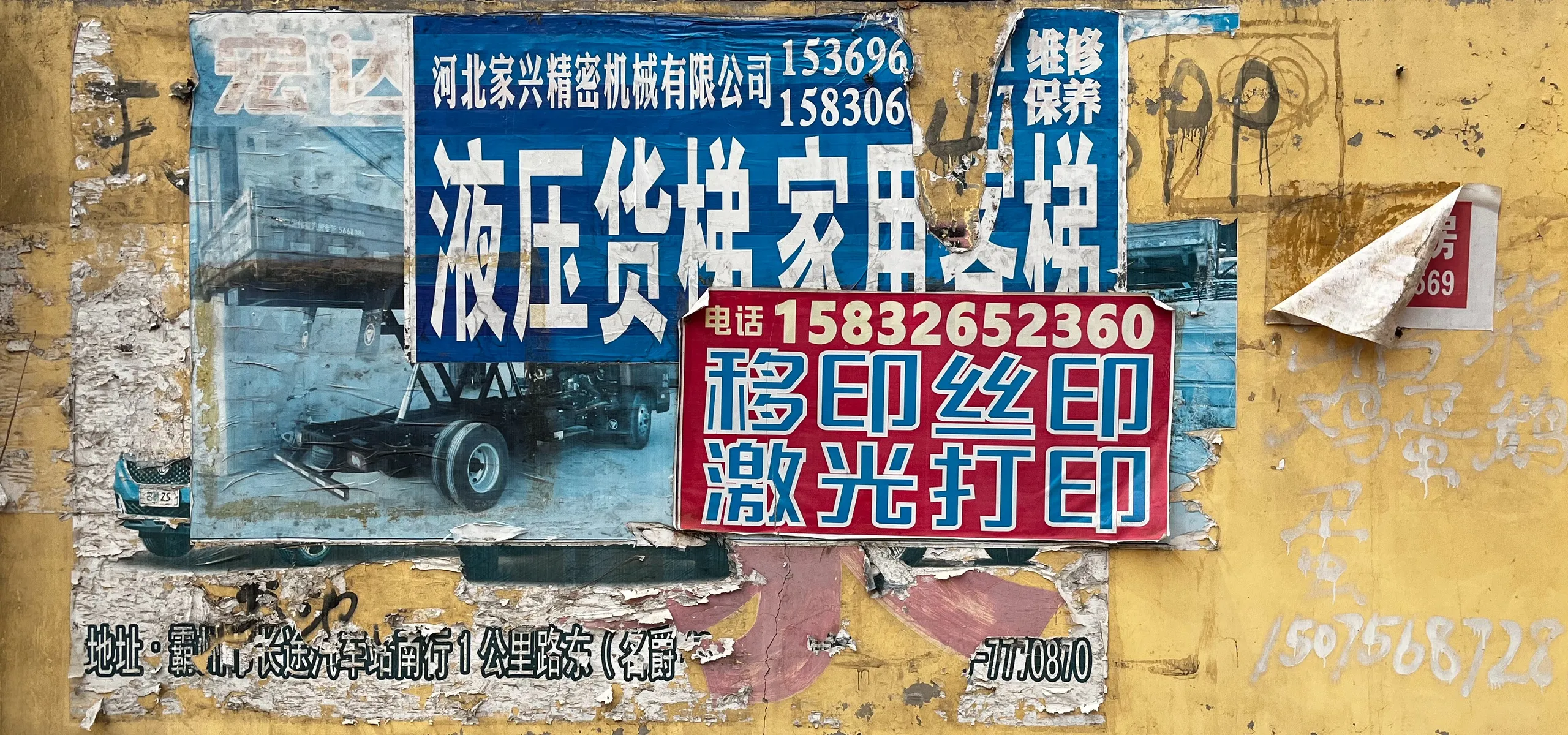

I did not look up the history of these 小广告 (“little ads”) at the time, but saw numerous newspaper editorials inveighing against the phenomenon of walls tagged with layers of paint, stickers, and ink, known as “urban psoriasis (城市牛皮癣).”

Whether or not you prefer clean walls (or find approved advertisements by registered corporations less distasteful), the evolution of guerrilla ads shows us how Chinese cities transformed from the late 1970s when market reforms brought a renewed spread of commercial advertising.

Serving urban drifters

The history of little ads is murky, but their first iterations may have been during what researcher Everett Yuehong Zhang termed the “impotence epidemic” of the 1990s. During a nationwide panic among men about their sexual performance, brought on by reasons he attributes to changing social attitudes and economic anxiety, major cities were covered with advertisements for clinics and medicine claiming to cure erectile dysfunction, premature ejaculation, and other male sexual maladies.

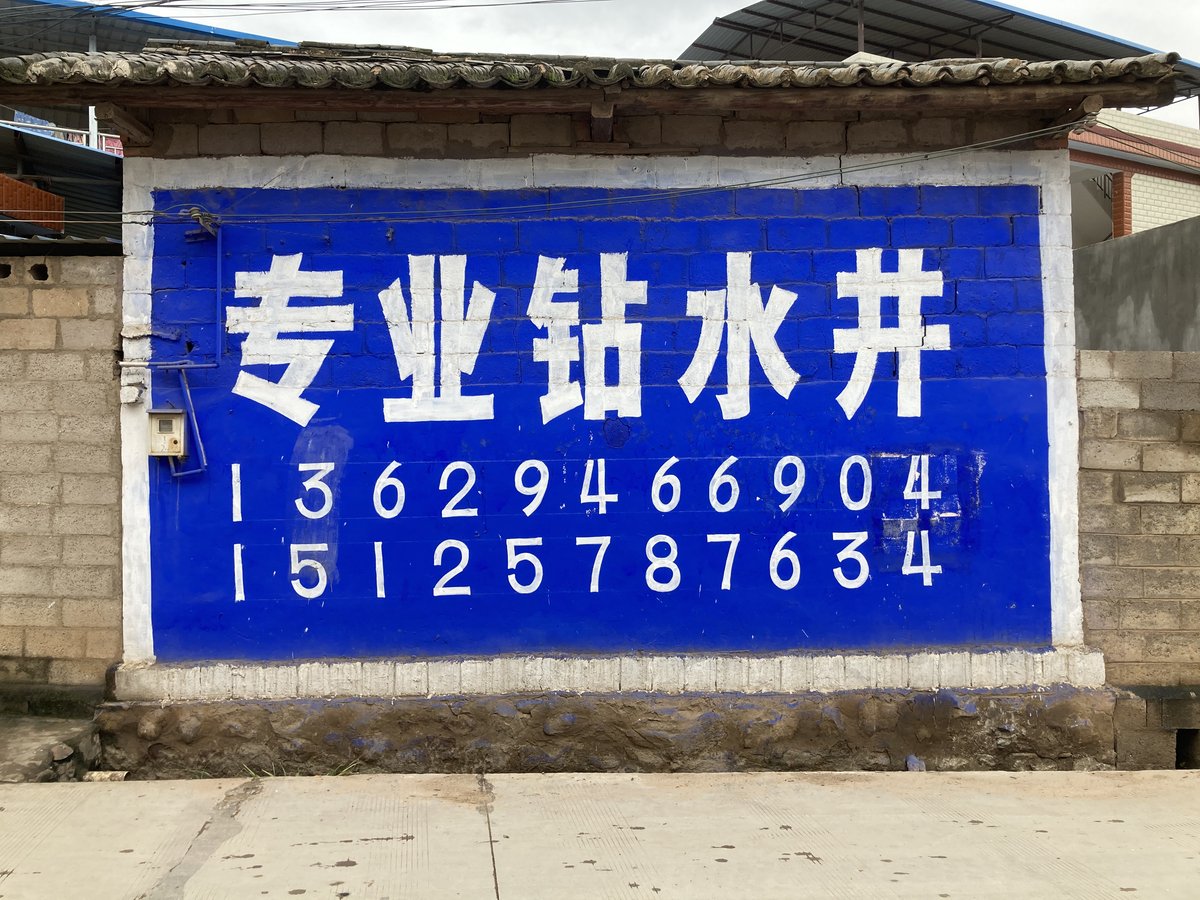

Comparing vintage examples of the impotence clinic advertisement with later little ads, however, there are some differences—namely, the earliest little ads pointed people to physical locations, and do not always include a phone number. The later little ads carried a cell phone number, suggesting they must have appeared after the establishment of mobile phone networks. The photographs by Zhang Xinmin, Xu Peiwu, and others from Shenzhen and Guangzhou, both in Guangdong province, in the 1980s and 1990s show us walls already loaded with these ads.

This later form—a service with a cell phone number—matches the temporary nature of settlement in the boomtowns of China’s new special economic zones. Cities like Shenzhen, Zhuhai, and Shantou were not unmanaged but certainly appeared governed less strictly than Beijing. As the floating population of internal migrant workers arrived, they needed documents to let them pass more smoothly.

They might need a certificate or diploma for a job. Renting an apartment might go more smoothly with certain official documents, such as a marriage license, a note from their work unit, or, depending on the period, permission from local authorities to work and live in the city. During a time when the means to verify the authenticity of the documents were limited, services advertised via little ads came in handy for those seeking opportunities in new cities. The little ads show us the anxieties not of the settled, satisfied families ensconced in the state economy or the bureaucracy, but the new urban working class, who were always on the move.

Little ads flourished in the cities of the Yangtze and Pearl River Deltas, hubs for the floating population who moved to work in the manufacturing industry that took off in the 1990s and early 2000s. This coincided with the spread of mobile networks across the country. While cell phones were available in China from the 1980s, it wasn’t until the early 2000s that China Mobile, China Unicom, and numerous small handset factories in manufacturing hubs spread phones and services across urban areas. Little ads spread with them.

Evolving with cities

When I spotted the ads as a student, it was already a decade since their first appearance. By the 2010s I saw advertisements, nearly identical except for the phone numbers, in Lhasa and Lanzhou, Datong and Dalian. In Nanjing, they advertised official seals and massages; in rural Jiangsu, they sold fake documents and Viagra. The form remained mostly the same, with only a few variations: a few characters describing a service, followed by a phone number were usually written freehand in spray paint, but, occasionally, stenciled advertisements could be spotted, and, increasingly in the 2000s, as stricter adherence to campaigns for urban beautification favored speed and stealth on the part of entrepreneurs, there were also stickers, which could be put up quicker than a stenciled sign.

The ads followed the spread of mobile phone networks and the transformative changes in urban Chinese work and life. This extended far beyond the first wave of private business people brave enough to xiahai—to “enter the sea” of the market economy—or the migrant workers that went far and wide to work in their factories. Even by the 2010s, urban young people of many social classes still had memories of growing up in work unit dormitories, where most of their family often worked—and there was little to prepare them for the reality of a rental market and highly competitive job searches.

I think of Xiao S, the young woman I tagged along with to attempt to buy a fake diploma. Although she was far from home, Xiao S did not fit the profile of migrant workers of the past: she left Inner Mongolia for Nanjing, completed a two-year degree, secured an office job, and was planning to get married to a man she had met at work. Their combined yearly income wasn’t enough for the couple to buy a house in the city and educate the child they planned to have, so her solution was to apply for a promotion with a raise. Unfortunately, the job required a four-year diploma, which she did not have.

I walked with her one morning up and down one of the central squares in the city, shopping the little ads inked on every surface. Xiao S eventually got her documents via one of these adverts, but finding them unsatisfactory, she resolved to tell her employer the truth. (She never bothered, however, and they never followed up. She is now an executive. Her daughter, who will take the college entrance examination this year, has never heard the story.)

Little ads for the digital age

Mobile phone networks, a floating population, precarious urbanization, and big city anxiety produced the little ad. The decades since their appearance have brought changes unseen in a century, but the little ad has survived in a modified form.

The “handle credentials (办证)” advertisement hasn’t disappeared, and neither have the medical ads, nor the phone numbers for locksmiths and plumbers that get painted or scratched into apartment building walkways, but the traditional little ad—touting for a black market service—is far less common than it was a decade before.

Campaigns by various municipalities to combat “urban psoriasis” probably played a role in the slow erasure, but a more important reason may be technological: With human resources departments now relying on online verification methods instead of notarized documents (fraudulent notary stamps were one of the services offered by little ads), it is harder to sneak through counterfeit documents. Before reimbursing an expense, a sharp accountant might check the QR code at the bottom of the receipt submitted to her. In years before, a fake driver’s license might pass police inspection, but that is unlikely now the police can instantly verify details in a database.

Although mobile phone use is now far more widespread than it was decades ago, the days of buying a knock-off handset and an unregistered SIM card are gone, making the business of the little ad entrepreneur a bit harder. Digital platforms are better at capturing attention, too: an advertisement running across a pirated movie, or hidden in a popup has a better return on investment than a spray-painted phone number in a public toilet. I suspect those who might be looking for shady legal services, impotence cures, or massages by busty country girls are more likely to turn to online search bars than graffiti.

The makers of little ads have attempted to keep pace. Stenciled QR codes have intermittently appeared in place of a phone number on little ads. The QR codes on shared rental bikes are still routinely plastered over with replacements that redirect users to online businesses. The little ad entrepreneurs are attempting to diversify.

Fading away

The little ad appeared to serve a type of city—growing like mushrooms after a rain, chaotic and desperate, full of possibility—and their rootless, anxious, hopeful population. The disappearance of the little ad may tell us about a wealthier, better-managed city. These are cities of homeowners. Cities entangled with digital platforms. Urban residents today are, if just as anxious, looking for solutions elsewhere.

It seems that everyone is content to let pass unmarked the age of the little ad. They were ugly, after all. They made the city less livable. Perhaps most residents have not even noticed their slow waning. They are just another remnant of the past that must be wiped out, like unregistered motorbike taxis, unauthorized vendors at street corners, and noise pollution. If there is a young woman like Xiao S out there now, desperate in a new city, I hope she will find better solutions than a counterfeit diploma from a graffitied phone number.

If that is the case—if this annoyance, too, can be cleansed—then it seems all the more important to reflect on the little ad, and the type of city and people that needed them.