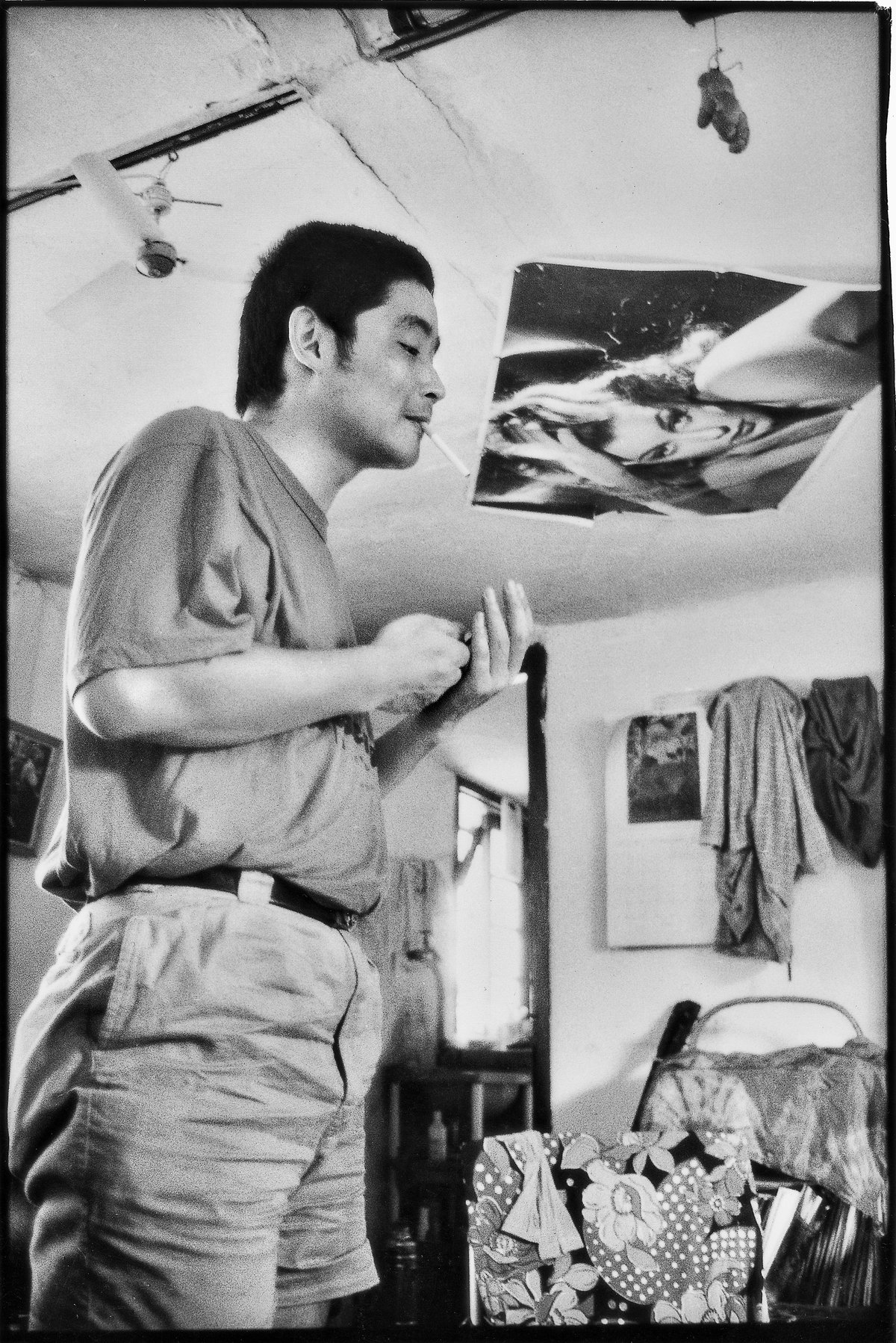

Su Tong’s new translated collection offers English-speaking readers a window into one of China’s best-known modern writers

Su Tong’s works are not for the faint-hearted. In the first tale of Missives from the Masses, a newly translated collection of 11 short stories from across the writer’s 40-year career, the protagonist goes into surgery knowing she will die from it. In another, an elderly zookeeper is forced to kill his animals for a biology teacher who helped get his grandchild into school.

Fans of the renowned writer will not be surprised by the darkness pervading the works in Missives. One of Su’s best-known works, the 1989 novella “Wives and Concubines,” which gained international fame as Raise the Red Lantern—the title of Zhang Yimou’s Oscar-nominated film adaption—tells the story of 19-year-old Songlian. She becomes the concubine of a wealthy merchant after her father went bankrupt and committed suicide. She faces loneliness, cruelty, and despair in the perverse fight for her “master’s” favor before descending into madness.

“I’m dedicated to the twisted destiny of characters since I’ve been so often awed by the uncertainty of life and history,” Su, whose real name is Tong Zhonggui, wrote in the preface to his 1992 novel My Life as Emperor. Over 30 years later, Missives carries on that dedication with stories that see mundane lives cast into disarray and fates upended by often trivial events. Rare respite from the depressing tone lies only in the dark beauty of grimy industrial factories or polluted outlets loaded with bamboo rafts, moss, dead fish, and garbage.

Su, born in 1963, is part of a generation of Chinese novelists who rose to fame in the 1980s. Su and peers like Ma Yuan and Yu Hua emphasized individual experiences, emotions, and fantasies while taking an absurdist turn away from traditional narratives based on reason, characters, and plot. They also experimented with new narration forms under the influence of postmodernism in the West. Later, in the 1990s, Su and others returned to more conventional characters and plot-driven narratives.

Su’s work featured in this new volume translated by Josh Stenberg spans from the 1990s to 2010s and offers English-speaking readers a new perspective to understand the often conflicted Chinese life of the last century. The stories here encompass both rural and urban settings and chronicle lives in fictional Chinese communities that Su modeled after his hometown of Suzhou in Jiangsu Province. It’s a welcome chance to read more from one of China’s most famous recent writers, and experience darker sides of humanity he reveals against the backdrop of the country’s tumultuous political and social changes during the 20th century.

The title story “Missives from the Masses” (1998) tells the story of Qianmei, a retired candy shop employee, who has spent her entire life informing on her colleagues and neighbors, and calling for their “rectification.” Now, even with deadly cancer spreading in her stomach, she continues to write letters of complaint and to report the hospital for maltreating her. The doctors know Qianmei’s illness is terminal but, with the higher-ups taking her complaints seriously, they agree to operate once more—a death sentence for the elderly woman.

This twisted, tragic tale sets the tone for the rest of the collection, where every story seems destined for death, disappearance, or dispute, and there are few satisfying conclusions. In “Early One Sunday Morning” (2008), for instance, teacher Mr. Li dies in a traffic accident while pursuing a butcher for a two-mao refund for selling him poor quality fatty meat instead of the pork knuckle his wife had demanded. “Cousins” (2004) tells a striking story of neighborhood competition and vanity through multiple generations in Maple-Poplar Village. As one family builds higher, uses better materials, and cooks better meals, another household falls deep into debt and trauma trying to keep up. In these, and several of the other stories in Missives, the tragedies that befall Su’s protagonists stem from their obsessions and pride.

Su’s characters do absurd, sometimes cruel things, but they are rarely unambiguous. “There is no need to draw a clear distinction between the good and the bad, or the kind and the evil; you can hardly tell them apart,” Su explained in a 2012 interview with ifeng.com. In “The Most Desolate Zoo on Earth” (1996), biology teacher Mr. Zhang, a self-proclaimed animal lover who turns fauna into “beautiful, perfect” objects for his study, helps get the zookeeper’s grandson into his prestigious school. In return, the zookeeper forgoes his belief that “monkeys are just like people” and kills his animals to help with Zhang’s specimen collection.

Several of the stories are from the perspective of children, often neutral observers to the grubby world of adults around them. In “The Most Desolate Zoo On Earth,” the narrator is a student who stumbles across the biology teacher’s trade with the zookeeper and witnesses the latter’s internal struggle between repaying a favor and protecting animals. “[Children] understand the world solely from their feelings, which is pure…and the world presents its real face,” Su told ifeng.com in 2012.

Missives also brings Su’s writing of female characters to English-speaking audiences. While many of his contemporaries, Yu Hua and Jia Pingwa for example, have been criticized for their one-dimensional or even misogynistic portrayal of women in their stories, Su has largely escaped that fate. A 2021 op-ed by the literary platform Douban Reading praised Su as one of China’s “best writers on women,” saying he depicted them as fully-realized protagonists with their “own survival logics, desires, and nature,” instead of giving them only supporting roles such as subjects of male protagonists’ desires for sex or other needs (which Jia has been notorious for). “The Western Window” (1992) and “Kitty” (1995), in particular, are two powerful women-centered narratives in Missives.

Though best known for his novels—such as The Boat to Redemption (2009) and Shadow of the Hunter (2013), both of which have been translated into English—Su has always defended the novella medium, lamenting on many occasions that publishers prioritize long-form works. He has written some 200 short stories, arguably containing his most cutting and powerful works. In his 1997 essay “Short Stories, Some Elements,” Su wrote that “short stories are bedtime stories for adults,” just like the fairy tales to children, “which can give one’s dull day a brilliant end.”

Through Missives, English-speaking readers can now look forward to their bedtime reading, despite the sometimes depressing subject matter.

Missives from the Masses was published by Sinoist Books on February 23.

Voice of the Masses: Su Tong’s Latest Translated Collection Reviewed is a story from our issue, “Education Nation.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.