Despite challenges like packed trains and nosy relatives, young Chinese used creative ways to ensure a peaceful Lunar New Year at home

While the Lunar New Year is mainly a joyous time for family reunions, it can also be stressful for those making the long trek to see relatives. The rush of travel and then the fuss of relatives scrutinizing younger generations’ life choices have long come in for parody on social media.

With record numbers traveling during the holiday this year, commenters online decried being crammed into railway stations “more packed than concert venues (候车大厅流量堪比演唱会 hòuchē dàtīng liúliàng kānbǐ yǎnchànghuì)” but with much less entertainment.

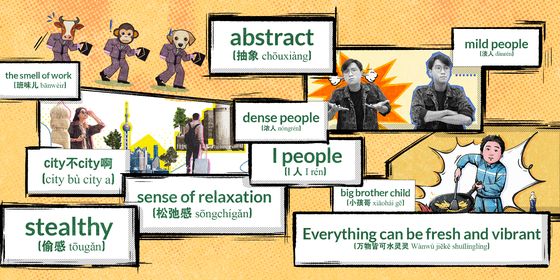

Travel hell is expected around the holiday rush, so many people brought entertainment like playing cards or snacks like sunflower seeds to while away the time. Some were even recorded cooking elaborate meals and brewing tea with a full set of tea utensils on train carriages. Netizens marveled at “the sense of relaxation of Chinese people during the travel rush (中国人民春运的松弛感 Zhōngguó rénmín chūnyùn de sōngchígǎn),” while claiming that “The world is a vast living room (世界是一个巨大的客厅 Shìjiè shì yí gè jùdà de kètīng),” humorously praising people’s ability to stay chill in any difficult environment.

Many urbanites headed back to their home villages for the holiday, or 回村过年 (huícūn guònián), and described stepping into a different world. Former “fashion bloggers (时尚博主 shíshàng bózhǔ)” or “social queens (社交女王 shèjiāo nǚwáng)” immediately reverted to simple village folk wearing the unofficial “rural uniform”—oversized pink cotton pajamas common in towns and villages—gathering firewood and washing dishes.

However, the holiday season isn’t all chill vibes. It can also become a hotbed for conflicts, especially when old traditions encounter new generations. The hashtag “Quarrel during the Lunar New Year (过年吵架 guònián chǎojià)” trended on the microblogging platform Weibo during the holiday, with many venting online that verbal disputes have become a special holiday tradition in their family over the years. How to cook the traditional reunion dinner, which side of the family to visit first, and how much 压岁钱 (yāsuìqián, lucky money) to stuff into red envelopes as gifts are all regular disputes.

The pressure to marry and have children (催婚催生 cuīhūn cuīshēng) is one of the most common sources of conflict, especially for women, during family gatherings. The tradition of “visiting relatives (走亲戚 zǒu qīnqi)” during the holiday means young people have no escape from “older generations (长辈 zhǎngbèi)” keen to bombard them with questions about every detail of their lives.

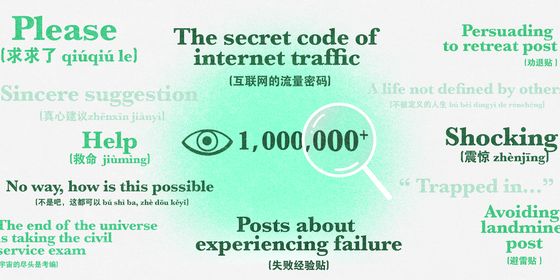

Exhausted by the nagging, netizens are taking to social media to share new “crazy tactics for handling questions from relatives (应付亲戚的发癫话术 yìngfu qīnqi de fādiān huàshù).” When asked, “How much do you earn in a month (一个月赚多少 Yí gè yuè zhuàn duōshao)?” they quip, “Not much, less than a hundred million yuan (没多少, 不到一亿 Méi duōshao, búdào yíyì).”

Meanwhile, they suggest answering “What job do you do (做什么工作的 Zuò shénme gōngzuò de)?” with “I just try to bravely be myself out there (在外面勇敢做自己 Zài wàimiàn yǒnggǎn zuò zìjǐ).” The golden rule is to “answer every question without actually answering (句句有回应,事事没着落 jùjù yǒu huíyìng, shìshì méi zhuóluò).”

A new motto for those subjected to unwanted questions during the holiday has emerged online: “Whoever advises me to get married, I’ll urge them to get divorced; if you ask about my salary, I’ll ask about your child’s grades. Give as good as you get. (谁劝我结婚,我劝谁离婚;你问我工资多少,我问你小孩成绩,礼尚往来。Shéi quàn wǒ jiéhūn, wǒ quàn shéi líhūn; nǐ wèn wǒ gōngzī duōshao, wǒ wèn nǐ xiǎohái chéngjì, lǐshàngwǎnglái.)”

Yet even though seeing relatives back home can be stressful and full of uncomfortable conversations, many still feel a pang of sadness when they head back to their everyday lives working in the city. “Being back in my rental apartment means I’ll have to pretend to be an adult again (回到出租屋的我:明天又要开始装大人了 Huídào chūzūwū de wǒ: Míngtiān yòu yào kāishǐ zhuāng dàrén le),” they lament online.