Small game developers vie for creative and commercial success in an industry often blurring the line between work and leisure

To make his latest video game, Yang Yi had to sell his house. After his previous game had its launch delayed by a licensing freeze in China’s game market in 2018, then suffered poor sales after finally releasing in 2020, Yang and his small team were in a “pretty dire” financial situation, he says. They had to take on external software development gigs to stay afloat before they ran out of money completely in 2021.

“We were broke,” the 36-year-old programmer from Zhejiang province tells TWOC. But Yang and his team continued working on their next title, Yi Xian, a combative card game inspired by Chinese mythology. Convinced Yi Xian would be a hit, Yang sold his home and funneled up to two million yuan of his money into the game to finish development and bring it to market. “There is nothing profound about this, I looked at it from all angles and was ready to accept the consequences,” Yang says, emphasizing that everyone on his team made sacrifices to make the game, including accepting minimum pay to keep the small studio viable.

Yang is not the only struggling video game developer in China. Small companies, especially, often fail to turn a profit and attract investment in an increasingly competitive environment. Keen for independence in their work, they accept poor pay and long hours in return for what they hope will be more creative freedom away from the country’s giant developers. They opt to directly release their games on international platforms like Steam but often end up like Yang: blurring the line between creative self-emancipation and self-exploitation—financial and emotional.

This is happening despite a booming domestic gaming market, which created record revenues of 303 billion yuan in 2023, mostly from mainstream free-to-play mobile games like Honor of Kings (published by Tencent) that generate revenue by selling in-game items (though this came after a pandemic-induced slump in 2022 saw close to 8,000 developers laid off from dozens of gaming companies, according to numbers collated by gaming media outlet Youxi Xinzhi).

Makers’ dreams

While stories of game makers selling their houses to finish a game are the exception, developers at small companies enduring grueling work conditions to follow their passion are common in China’s gaming industry. The 2017 documentary Du Xing, well-known in the country’s game-making circles, chronicles five game designers’ hardships and financial failures.

Li Yuanyang, for example, founded a small game studio in 2013 to develop his two-player platform-jumping game Button Button Up! “We each get 2,000 or 3,000 yuan now, just enough to get by,” he says in the documentary, talking about his team’s low monthly income at the time. When Li pitches his game to internet giant Baidu, one of the executives warns him: “It’s not easy to profit from indie games. There are very few successful cases.”

After two years of failing to find a publisher for the game, Li self-published on the international distribution platform Steam in 2019. The platform takes a hefty 30 percent cut from every sale, and Li’s game, priced at 11.99 US dollars, was a financial failure, with a meager 86 reviews on the platform at the time of writing.

“Spending a lot of time and energy to make one game, which is then only released on Steam and flops—that’s actually a very common outcome among game makers here,” Wang Mei, a representative of a major Chinese game publisher, who asked to use a pseudonym for this piece, tells TWOC.

Learn more about China’s indie game industry by listening to this episode of the Middle Earth podcast.

Li and his team eventually released another version of the game for Nintendo’s Switch console in 2020, the culmination of several years of development—to disappointing reviews: “It’s not going to win any awards and it probably won’t become your favorite game of the year,” reads one reviewer’s crushing verdict. Li and his team dropped off the radar after that.

“Game designers in China face significant challenges related to self-awareness, market understanding, and product expectations,” says Simon Zhu, founder of the China Indie Game Alliance (CIGA), the largest industry association for independent game-making in China. “For small teams, it’s essential to maintain control over project boundaries and cost. Understanding the market and having a clear idea of what your product will be and where it will fit is crucial,” he says.

This is where investors and publishers come into the fold. “In the game industry’s value chain, they are essential…They complement and support game developers, it’s a mutually beneficial relationship,” Zhu, who founded CIGA in Shanghai in 2015, tells TWOC. However, independent game makers face huge competition to find publishers willing to invest the money necessary to bring their games to China’s vast domestic audience.

Hunting investment

On the floor of the WePlay gaming convention in Shanghai last November, game maker Liang You, wearing a rimmed black hat similar to the one Australian bushman Crocodile Dundee made famous, is on the hunt for investors for his latest game. Liang, a 29-year-old from Shaanxi province, works as the creative director on the PC platforming title Crab Rhapsody which sees players control a crab climbing a tower, picking up items—the crustacean can hold one in each pincer—and fighting off waves of enemies.

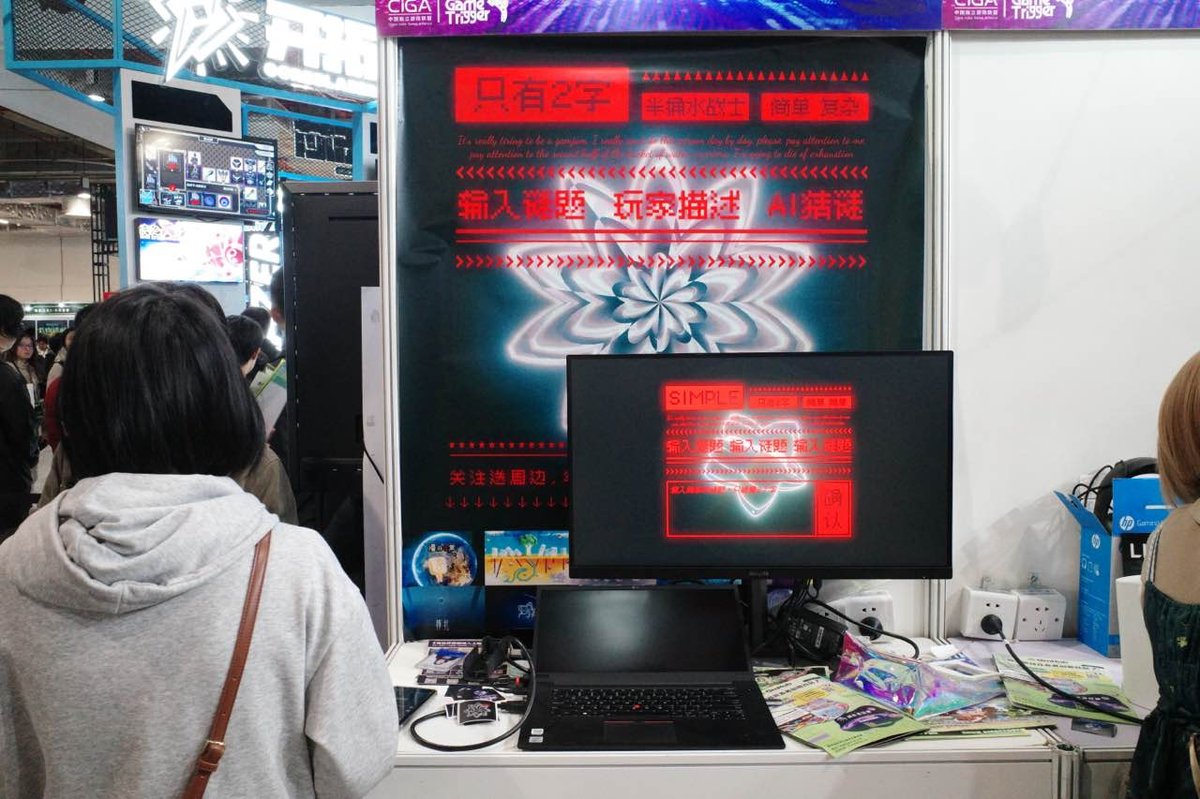

Liang and his small game development company are one of many displaying their games at perhaps China’s largest gaming convention, which has been around since 2017. After a two-year hiatus, 2023’s WePlay had doubled in size since its last edition in 2021.

“If you want money from investors, you come here,” Liang tells TWOC over the pew-pew-pew of convention-goers testing out Crab Rhapsody at his booth. A small speaker is dangling from the screen at Liang’s exhibit so players can hear the game’s award-winning sound design. Still, the audio is drowned out by the noise of dozens of other booths showcasing Chinese games and droves of players scrambling to try them out.

Liang—like many other young game makers at WePlay—needs money from investors, and eventually support from a publisher to bring his game to market and help with things like advertising and localization. In China, the developers create the game, the investors finance it, and the publishers help bring it to market.

Liang restarts the game over and over as dozens of convention-goers mill around the floor and come to try it out. The title opens with a big band of crabs playing various musical instruments. “I love rock music but can’t play an instrument, so I wanted to find a way to bring that into a game,” says Liang, motioning at the screen as the crab picks up musical instruments that add to the background music. These small creative details are what Liang hopes will set his game apart in the fight to attract investors’ attention.

But many independent game developers in China are “immature” according to Wang, the game publishing representative, with poor division of labor and a lack of managerial rigor. This often puts publishers and investors off. “It’s not uncommon among game makers that the work is not clearly defined, so they can’t do proper planning during the development process and often end up arguing and eventually splitting up,” Wang tells TWOC.

Liang, who only began making games during the pandemic after seeing how games can provide comfort and help people through difficult times, has tried to model his small team after more established game studios, with clearly defined roles and departments. Liang is in charge of creative direction. A lead programmer and a lead composer, both from the US, manage small sub-divisions of coders and sound designers.

He is trying to combine the creative spirit of independent game makers with a sustainable business model. “If you’re under pressure, you can’t create,” he says. But without investment from major companies like Bilibili (primarily a video streaming platform but also a game publisher), small developers often resort to more risky tactics to fund their games.

Many opt for the early access model—putting a very early, unfinished version of the game out for players to buy and try. But in China this model, while theoretically able to generate income during development, has been discredited. “There were too many games in the past that were put out in such a bad state and players felt ripped off,” says Yang.

The Chinese-made game Tale of Immortal, for example, was released as early access in January 2021 and then remained in that unfinished state for over two years, with many players lamenting the deteriorating quality of the updates and reviews on Steam becoming increasingly negative. Another game, The Scroll of Taiwu, is now entering its seventh year of early access on Steam, with players complaining about disappearing features or other changes that affect play, leaving some who spent money early with a wildly different—or even unplayable—game now.

“Users are quick to give negative reviews,” says Simon Zhu about the publishing environment on Steam. The negative reviews can adversely impact sales, which, in turn, may lead to longer development times, and could even prevent a game from progressing beyond the early access phase.

For the players

Other passionate developers try to liberate themselves from the risks and pressures of the commercial game-making industry by developing as a hobby only. Chen Xi, a 24-year-old who works as an illustrator in Guangdong province, developed an AI-based guessing game in her spare time. “Write a brief description of a two-character Chinese word, without including those characters, and see if the AI can guess the word,” Chen explains. When someone types in a brief description (“something that lives up there”), the AI guesses 天使 (angel) correctly after a few seconds.

Chen dropped out of high school and started working at 16 due to health issues and severe exam anxiety in the face of the ultra-competitive college entrance exam. “My family was totally opposed to me not going to school at the time and my mental health suffered badly but the little sense of achievement I got from making my own games gave me a lifeline I could hold onto,” she tells TWOC.

Unlike Liang, Chen isn’t concerned with finding investors to make her game commercially viable. “My goal is to get some happiness and a sense of achievement from the creative process itself. I don’t have to worry about whether I can go on making the game or finish it,” she says. But she’s still wary of being pulled into the commercial sphere, overworking to develop her games, and falling into self-exploitation. “In the video game industry...a clear distinction between work and leisure has crumbled away,” as video game researcher Brendan Keogh from the Queensland University of Technology warned in a recent paper about the risk of self-exploitation among amateur game designers.

For developers like Yang Yi, on the other hand, who have risked it all to get their games finished and published, financial worries remain. Even though Yi Xian, after a year of early access, has racked up over 3,000 mostly positive reviews on Steam, Yang is a long way from making back his 2 million yuan.

Now, the official version of Yi Xian is finally finished and will be released on January 22—free-to-play. Yang hopes this model will draw in more players and generate enough revenue through in-game purchases alone for continued development. “[My wife and I] now live in a rented apartment,” Yang says. “Whether our financial situation improves will depend on how things go from January 22.” With a little luck, Yang won’t have to sell any more possessions to keep his game-making dream alive.