Learn how the character 文 went from being a term for the uncivilized in ancient China to referring to literature, refinement, and culture in the modern day

Some 2,000 years ago in the Yue Kingdom, far from China’s center, dangers lurked everywhere. On China’s southeastern coast, beasts were said to roam the land while oceans and rivers hid evil flood dragons, lesser monsters that caused storms and tsunamis before becoming full-fledged dragons after enduring a millennium in freezing water.

According to “Treatise on Geography (《地理志》),” a column from the 2nd century historical classic Book of Han (《汉书》), the Yue people devised an unlikely way to fend off these waterborne threats—they cut off their hair and tattooed their bodies to look like the son of the dragon, protecting them from attacks. This custom was seen as barbaric by the people in Central China, who used the idiom 文身断发 (wénshēn duànfà, tattooed and hair severed) to describe what they viewed as uncivilized practices in undeveloped areas. The phrase, though rarely used outside of historical context, is still in dictionaries today.

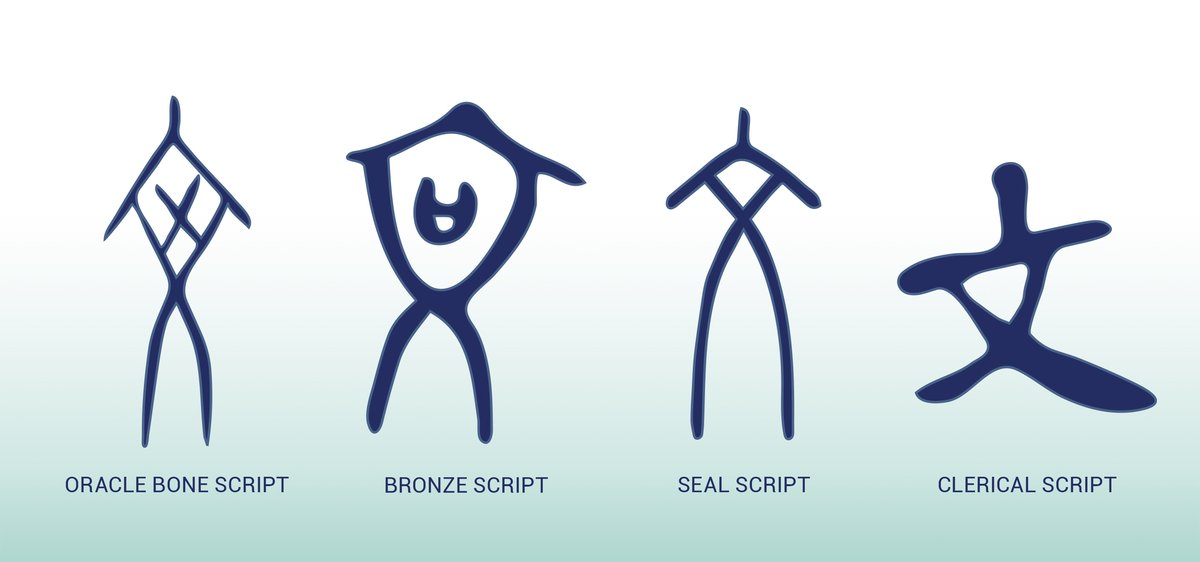

The character 文 (wén) first appeared in oracle bone script over 3,000 years ago. The Analytical Dictionary of Chinese Characters (《说文解字》), compiled in the 2nd century, defines it as originally referring to irregular drawings and intertwined patterns. In its earliest forms, the pictograph is a vivid depiction of a person with crisscrossing figures on their chest. By the time the small seal script developed in the 4th century BCE, the entwined patterns had all but disappeared and the character began to resemble its modern form.

The meaning of 文 evolved to refer to more systematic patterns and, eventually, Chinese characters. The preface to the Analytical Dictionary explains that Cang Jie (仓颉), the mythical inventor of characters, created the Chinese script in imitation of the shapes of things. These patterns were thus called 文. When simple imitations no longer sufficed, he created more complex characters by combining a phonetic part with a meaning-signifying unit. These compound characters became known as 字 (zì). This distinction between 文 and 字 can be observed from the Chinese title of the Analytical Dictionary, which means “explaining wen and dissecting zi,” as the former is a single unit while the latter can be split into parts.

Today, illiterate people are said to be “blind to characters,” or 文盲 (wénmáng), and guessing a character’s meaning based solely on its appearance is 望文生义 (wàngwén shēngyì).

Characters make up writing, and 文 naturally became associated with literary composition. An elegant piece is said to be “exquisite in style (文笔优美 wénbǐ yōuměi)” or hint at “splendid literary talent (文采斐然 wéncǎi fěirán).” An effortless writer is described as having “literary inspiration gushing out in a stream (文思泉涌 wénsī quányǒng).” In Classical Chinese (文言文, a form of the language reserved mainly for writing by the literati before the 20th century), 文学 (wénxué) referred broadly to all kinds of written scholarly works. But in the 20th century, as new concepts came to China from the West and Japan, the term began to specifically designate the discipline of literature. There is 文艺 (wényì, literature and arts), 文艺汇演 (wényì huìyǎn, artistic performances), and 文科 (wénkē), a catch-all term for humanities and social sciences.

A society with a written language is considered a civilized one. As such, 文 is also present in 文化 (wénhuà, culture) and 文明 (wénmíng, civilization, civilized). Valuable objects from ancient civilizations are 文物 (wénwù, artifacts), while linguistic relics from ancient Chinese are known as 文言 (wényán), in contrast to the modern vernacular (白话 báihuà).

As writing in the vernacular only became popular in the 20th century, some authors still can’t help but mix the traditional with the spoken, a style called 半文半白 (bànwén bànbái). The style is often frowned upon by advocates of a modernized literary form. The character also refers to phenomena beyond direct human control, such as 天文 (tiānwén, astronomy) or 水文 (shǔiwén, hydrology).

A civilized individual is not supposed to be violent, so many words including 文 imply elegance and gentleness. To be 斯文 (sīwén) is to act or speak with politeness and reserve. But if a self-professed person of culture indulges in unseemly deeds, they are said to “have their elegance swept away (斯文扫地 sīwén sǎodì).”

Mildness is the opposite of bellicosity, hence, 文 was often contrasted with 武 (wǔ, military prowess) in the sometimes violent world of ancient China. Someone skilled in both writing and fighting is 文武双全 (wénwǔ shuāngquán), though many Chinese rulers, afraid that military leaders could pose a threat to their power, adhered to a national policy of 重文轻武 (zhòngwén qīngwǔ, valuing intellectual power over physical) among their officials. Interestingly, this contrast is now also applied in the kitchen. Cooks need to know when to switch between “high heat (武火 wǔhuǒ)” and “low heat (文火 wénhuǒ).”

Being cultured doesn’t mean flaunting one’s sophistication. As Confucius is recorded telling his disciples in The Analects (《论语》), “If one’s nature is more conspicuous than one’s refinement, they appear uncultivated; whereas in the opposite case, they appear pretentious. Only when the two qualities are well-balanced do we have a person of virtue. (质胜文则野,文胜质则史。文质彬彬,然后君子。Zhì shèng wén zé yě, wén shèng zhì zé shǐ. Wénzhì bīnbīn, ránhòu jūnzǐ.)” Centuries later, this remains a worthy aspiration.

How a Character That Once Referred to Barbarians Now Represents Civility is a story from our issue, “Education Nation.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.