Reported sightings of the mythical creature have captivated people in China for centuries

Athunderous scream shattered the tranquility of the farmland in Tianzhuangtai, a small town in Yingkou, Liaoning province. It was early July 1934, and a dragon had just fallen from the sky.

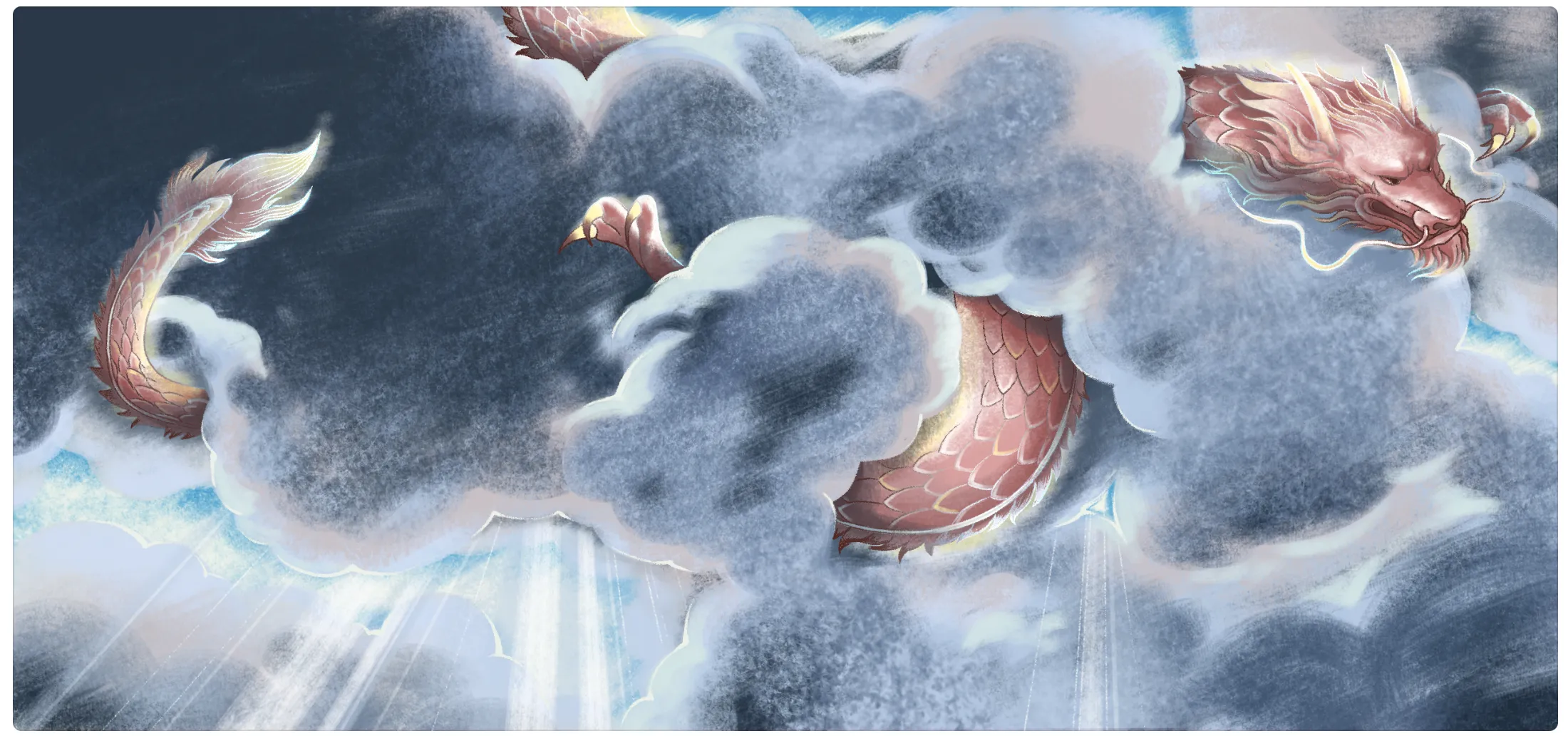

Locals claimed they had seen a magnificent creature with two horns, razor-sharp claws, and scales adorning a ten-meter-long body—exactly how dragons, or long (龙) in Chinese, are depicted in ancient paintings.

To protect the legendary being from the sweltering weather, bystanders poured water over it and constructed a shelter out of rush mats to keep it in the shade. Monks were invited to perform a religious rite in hopes of aiding the creature’s recovery, but the dragon vanished after a few days of heavy rain.

On July 28, Shenyang-based newspaper Shengjing Times reported a similar incident in Yingkou where the dragon fell from the sky. The incident allegedly led to the destruction of houses and boats, the derailment of a train at the station, and resulted in the deaths of nine people.

Despite the dragon being a mythical creature, sightings of the auspicious beast have been common throughout Chinese history. Revered as a symbol of power, strength, and good fortune, the creature has fascinated everyone from peasants to officials to emperors. In the Eastern Han dynasty (25 – 220) Analytical Dictionary of Chinese Characters (《说文解字》) by Xu Shen (许慎), a dragon is described as a long creature adorned with scales, capable of morphing its size and length. It was said to ascend to the sky during the spring equinox and dive into the sea during the autumn equinox. There is no mention that it may not be real.

Emperors were identified as the sons of dragons to consolidate their power and authority. Biographies of Immortals (《列仙传》), the oldest surviving Chinese hagiography of Daoist immortals written during the Western Han dynasty (206 BCE – 25 CE), even recorded how ancient people raised and rode dragons.

In 80 CE, eight yellow dragons were spotted in the Xiang River in present-day Yongzhou, Hunan province, according to the Book of Later Han (《后汉书》); and in Supplement to the Annals of the Tang (《唐年补录》), Jia Wei (贾纬), a historian from the Five Dynasties (907 – 960), recorded an incident where 40-meter long dragon, was found dead with a grievous injury to its throat.

Even in modern times, sightings continue. In 2006, in a cave in Kunlun mountain in Northwest China, rumors spread that a tourist there had been eaten by a dragon. Subsequent research found that the alleged man-eater was merely a salamander.

One sighting in Tianjin in July 1998 still puzzles locals. Residents from Xiditou village claimed to have spotted a dragon’s claw, large and dark red, moving in the sky during a stormy night. One villager even took out a camcorder from home to film the scene.

After about half an hour, lightning illuminated the sky revealing a huge dragon. It quickly vanished, leaving behind six large, red scales on the ground, and a burning fishy smell. Next to the scales was a snapping turtle. Three hours later, experts and reporters from Tianjin TV Station arrived and interviewed witnesses, and watched the recording. However, the professionals concluded it was merely a natural weather phenomenon. The locals didn’t buy this explanation and even went on to host a ritual to worship the dragon.

The dragon sighting in Tianzhuangtai seemed to be supported by more evidence. Around 10 days after the dragon flew back into the sky (according to locals), villagers discovered the body of a mysterious creature, stinking of blood, in the reeds next to a river. Its scales filled two large baskets and it made a sound like a cow’s moo as it died, according to The Chronicle of Yingkou (《营口市志》), a history of the region by the local government published in 1986.

The discovery caused quite a stir. After the police transported the bones to an open space nearby for public display, people flocked from across the country to observe the skeleton, resulting in a shortage of train tickets to Yingkou. Later, the skeletal remains were kept as specimens at a local school, but in the chaos of wars over the next decades the remains were lost.

The dragon sighting attracted new attention in 2004 when Sun Zhengren, a Yingkou local in his 80s, claimed he still had bones from the skeleton. That year, Approaches to Science, a TV show by state broadcaster CCTV, revisited the case, enlisting scientific experts to conclude the dragon mystery. Xiao Suqin told the program that she first saw the dragon when she was nine years old. She remembered seeing something coiled on the ground with its tail curled up, and two claws stretched out from its abdomen.

Through investigations, interviews, and scientific analysis, a team of experts concluded that the remains Xiao, Sun, and other villagers saw in Yingkou belonged to a Baleen whale. The protruding horn on top of the skeleton that was later put on display was a result of a misplaced lower jawbone inserted into the eye socket. They also tested Sun’s dragon bones and found they were the fossil of a horse, dating back to 2.5 million years ago—extraordinary, but not mythical.

Despite scientific explanations disproving dragon sightings in the present day, many in China still wonder about the existence of the auspicious creature. For some, the only evidence they need is the dragon’s inclusion as one of the 12 Chinese zodiac signs, next to very real creatures like dogs, chickens, and monkeys.