As events shut down and regulations tighten, China’s remaining independent movie festivals fight to stay relevant and afloat

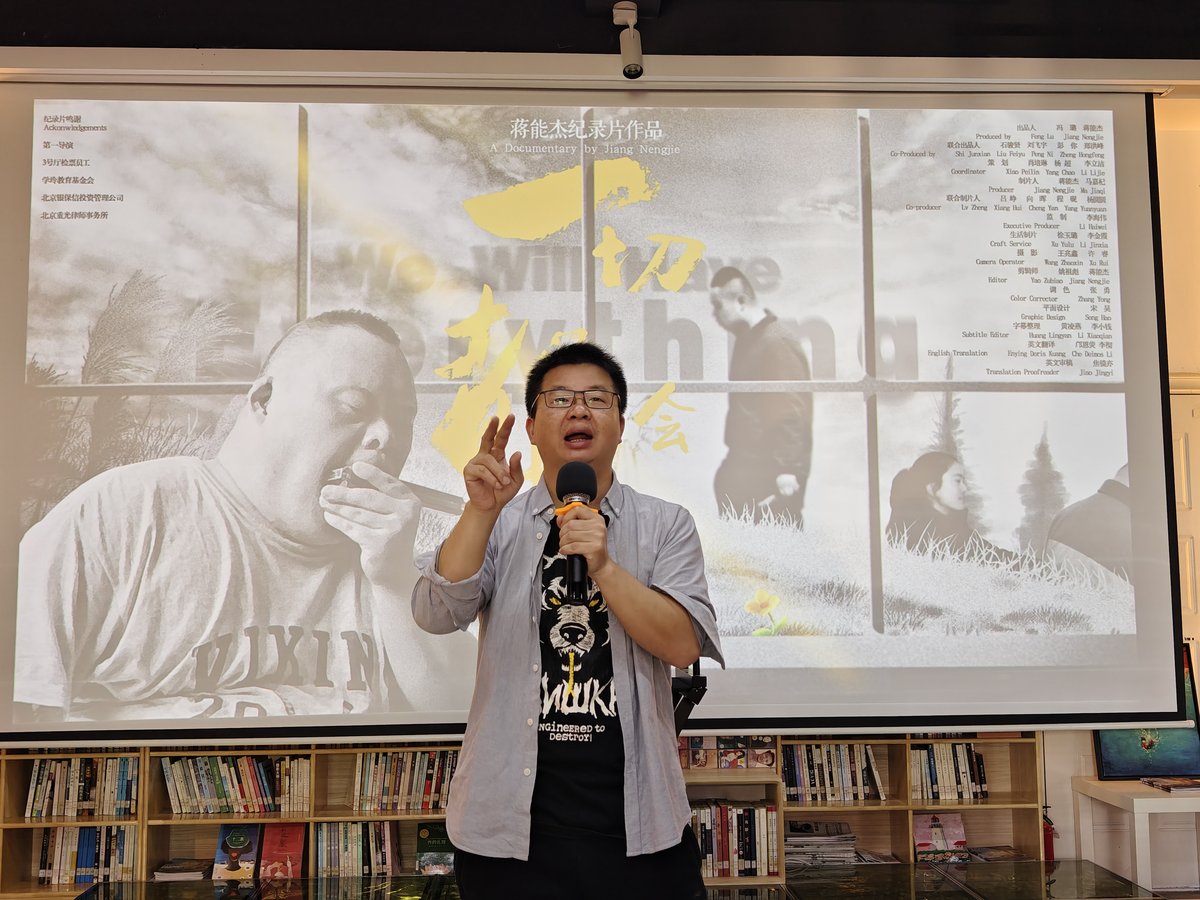

When the China Independent Film Festival (CIFF) announced its closure in 2020, many scholars and filmmakers mourned the end of an era. “There are not many independent film festivals left in China,” says Jiang Nengjie, an independent director based in Guangzhou, Guangdong province. “Independence is a sensitive word.”

Hailing from a village in Hunan province, Jiang is known for making documentaries that center the lives of rural or marginalized people such as “left-behind children,” war veterans, and miners afflicted with pneumoconiosis (a fatal respiratory condition also known as “black lung”).

Listen to Middle Earth Podcast episode “FIRST: Behind the Scenes at China’s Sundance” to learn more about China’s film festivals

He is also renowned for refusing to submit his films for official approval for screening in China. Instead, he distributes them through private screenings, USB drives, or by uploading his works onto cloud servers—earning him the moniker “Baidu Cloud Director.” “Independent filmmaking resonates with me as a means of personal expression—an inherent right I uphold,” he tells TWOC, explaining he wants to retain full creative control over his films.

Still, for emerging filmmakers, it’s not practical to avoid film festivals altogether. Aspiring filmmaker Huang Wenli, like many of his peers, views film festival submissions as a crucial avenue to garner visibility for his works. “The initial step for independent filmmakers to gain visibility is through film festival submissions,” says the 27-year-old, who transitioned into filmmaking after studying broadcast journalism in college and working at a video streaming company. He has made three short films in the last four years.

Emulating job applications, Huang actively submits his films to multiple festivals, both domestic and international. “Most domestic festivals offer free submissions...so I frequently apply to numerous festivals to increase exposure for my works.”

Participation often leads to exposure to wider audiences, networking opportunities with industry professionals, and, in some instances, serves as a launchpad for breaking into mainstream cinemas. A well-known success story in the industry is that of Xin Yukun, whose debut feature, The Coffin in the Mountain, premiered at the FIRST International Film Festival in 2014, where it won the title of Best Film, then made its way to mainstream cinemas the following year and is one of China’s best-known crime dramas today. Other filmmakers, such as Fan Lixin, Ma Li, Hao Jie, and Wen Muye have also experienced career boosts from their works appearing at FIRST and other festivals.

Some, like Jiang, continue to take a principled stance. “Independent films should exist devoid of restrictions and censorship. True independence embodies the freedom for unbridled and critical creative expression,” he tells TWOC. For emerging filmmakers still trying to break into the scene, however, the challenge is to find their feet within the increasingly strict regulatory landscape, as well as a recent wave of regional independent film festivals—not always consistent in quality, and involving a variety of actors like local governments and young filmmakers—that are surfacing across China.

Independent screenings

In the Chinese context, the term “independent films,” or 独立电影, typically refers to uncensored, self-funded, and creatively-driven works. This genre began to flourish notably in the 1990s, attributed in part to works like former TV director Wu Wenguang’s 1990 documentary Bumming in Beijing, a documentary on the lives of five visual and performing artists who had migrated to Beijing from different parts of China. In the same year, Zhang Yuan’s feature film Mama brought attention to the hardships faced by people with disabilities.

Three major independent film festivals opened in the following decade: CIFF and the Yunnan Multi Culture Visual Festival (Yunfest) in 2003, and the Beijing Independent Film Festival (BIFF) in 2006. These non-governmental and not-for-profit film events became instrumental in not only promoting independent cinema but also in nurturing a community of filmmakers dedicated to exploring diverse narratives and experimental storytelling in a landscape often constrained by mainstream commercial cinema norms.

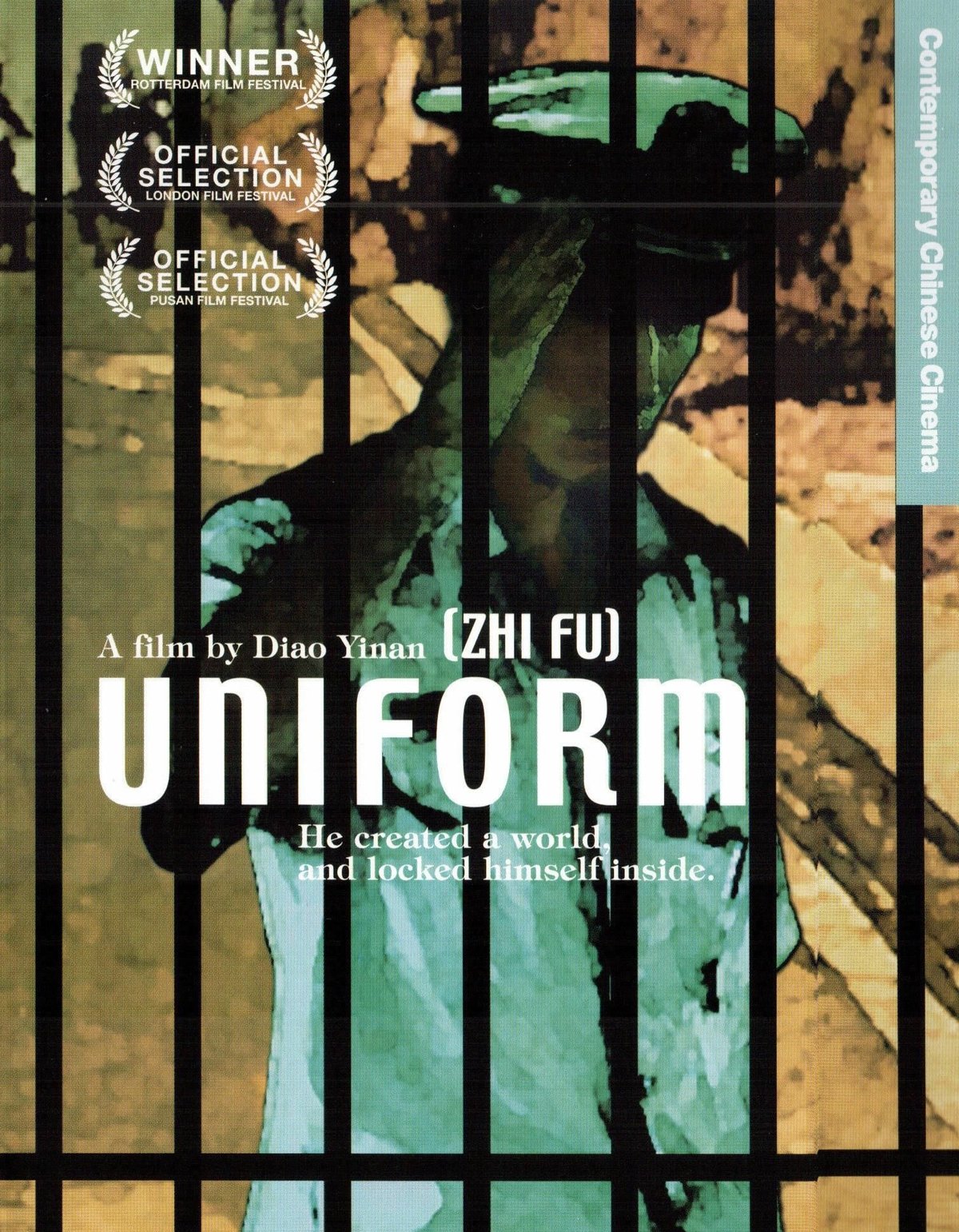

Many films shown at the festivals did not obtain legal distribution approval and tackled issues, such as homosexuality and political history, that are deemed sensitive or inappropriate by the authorities. For example, future Berlin Golden Bear winner Diao Yinan debuted in 2013 at CIFF with Uniform, which follows a young man who discovers unprecedented power after he dons an abandoned police uniform.

Despite their significance, these burgeoning festivals struggled with financial constraints and stringent regulations. In China, cultural and sports events involving more than 200 participants require permission from local authorities; a time-consuming bureaucratic hurdle that can often lead to arbitrary rejection, posing challenges for independent film festival organizers.

Moreover, public film screenings in cinemas or online require official approval via the coveted Film Public Screening Permit, colloquially referred to as the “Dragon Label.” Filmmakers could be asked to remove elements considered sensitive or might be denied screening rights altogether. Some, like Jiang, are determined to not apply for a Dragon Label, citing a desire to maintain their creative independence and critical voice.

For decades following the introduction of the Dragon Label in the 1990s, a gray area persisted where independent film festivals could screen unlabeled and uncensored works. “The Chinese independent film festivals have created an alternative public sphere in a restricted social environment, effectively sustaining the seemingly unsustainable independent film circle,” scholars Sabrina Qiong Yu and Lydia Dan Wu observed in a 2017 paper.

Since 2017, however, China’s film industry has undergone a marked shift toward increased restrictions. In March of that year, China implemented its inaugural law on filmmaking and the film industry. Under these regulations, the production and screening of films without official approval are strictly prohibited, subjecting violators to fines ranging from thousands to millions of yuan. Serious breaches may result in a five-year ban on filmmaking or screening rights.

The escalating censorship measures, particularly over those with the potential to offer critical perspectives, resulted in the gradual closure of all three major independent film festivals. Yunfest ceased operations in 2013, followed by the suspension of BIFF a year later by local authorities, who additionally confiscated the festival’s 10-year-old archives. CIFF attributed its termination in 2020 to the challenges of maintaining absolute independence and relevance in an increasingly restrictive environment, as stated in the festival’s official announcement.

Regional disruptors

During this wave of closures, FIRST International Film Festival emerged and has become arguably the most recognized independent film festival in China. Initially known as the “Student DV Film Festival,” it began in 2006 as a campus event celebrating the works of young film graduates at the Communication University of China in Beijing. In 2011, it was rebranded as FIRST, broadened its scope beyond student films, and relocated to Xining, the capital of Qinghai province, where it has been held every year since.

Founder Song Wen calls FIRST a “long-term film culture public undertaking.” Over the past decade, FIRST has pursued a mission to discover, nurture, and showcase the talents of emerging filmmakers (though, unlike most other domestic festivals, submission isn’t free). Beyond its main competition and exhibition segments, the festival offers young filmmakers financing opportunities, workshops, and networking with established distributors. These offerings are significant in China, where content creators may have less diverse sources of financing than their counterparts in Western countries.

Both Huang Wenli and Song stress the pivotal role of education in reshaping China’s film industry. “We don’t have enough educational resources specialized in film. What’s taught in schools doesn’t necessarily work in the industry,” says Song. “Film festivals are a real source of education for creators where they can receive critical feedback; there is an urgent demand for more specialized and practical courses based on filmmakers’ needs.”

Huang also submitted his film to FIRST, but didn’t get selected. Apart from FIRST, he has witnessed a rise in privately-run regional film festivals and specialized exhibitions, such as the Jiangxi Wazi Youth Film Festival. These events, where he has screened some of his films, often focus on short films and curate screening or competition programs for local talent, to foster and showcase regional film creators.

Huang recognizes these small-scale festivals’ role in providing opportunities for young filmmakers to exhibit their works, which encourages more content creation. “These events are instrumental in unifying local creatives and consolidating resources,” he notes. He highlights the collaborative efforts between these regional festivals and educational institutions, and their screenings and networking events that help filmmakers within the same region forge connections.

“Although the early works of directors may be rough and imperfect, they offer insight into the future potential of these young creators, their social concerns, storytelling ability, and critical awareness,” Song tells TWOC.

“This connectivity among regional filmmakers not only fortifies the local film industry but also presents an opportunity to break the dominance of major festivals in big cities.” He envisions these initiatives as potential disruptors, transcending the dominance of major urban hubs and amplifying the voices and narratives emerging from diverse regions across China.

Whose festival?

With a similar vision, some young filmmakers have taken matters into their own hands by creating film festivals. In 2022, 24-year-old independent director Cui Xiwei founded WH Youth Film Festival in Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province. “Wuhan’s film culture is less developed compared to other cities like Chengdu and Xiamen where they have many high-quality film festivals,” says Cui. One of his goals is to elevate the city’s cultural influence.

The project also aligns with a personal ambition: to make his feature film debut. “I hope through the festival to connect with other young creators from the area and potentially assemble my own film crew,” Cui tells TWOC.

The journey to establish WH has involved navigating logistical hurdles and liaising with local authorities on matters such as getting approval to include the city name in the film festival’s name. Earlier this year, Cui secured approval from the local Federation of Literary and Art Circles, an organization overseen by the Communist Party of China responsible for literary and art events. Now, Cui and his team are busy selecting venues, assembling judging panels, crafting a visual identity, and making promotional materials in preparation to launch the festival by early 2024.

Paradoxically, Cui believes regional government support can be key for a festival to maintain independence and expand its cultural influence in the current environment. “Most of the regional independent events rely on private universities and institutions like the China Film Association [to organize them],” he says. While WH receives no state funding yet, Cui is exploring collaboration with the government-backed Guanggu development initiative as a source of future financing.

However, films showcased or honored within independent events might not consistently resonate with mainstream audiences. According to Wang Runjie, a cinema and media studies PhD student at the University of Washington in Seattle, while some films gain significant acclaim within the festival circuit, their impact often fades once the festivals conclude.

Rather, Wang emphasizes the impact of film festivals on cinephiles or film fans, giving a boost to the larger cultural environment. “These film festivals are not only about showcasing films. Beyond that, it’s more of a carnival for cinephiles. They have played a significant role in shaping China’s film festival culture.”

Wang takes FIRST as an example, calling it “one of the world’s most unexpected indie cultural scenes” in an article published in 2022. “The annual event is simply enthralling for the younger generation in China, regardless of whether or not they are filmmakers.”

Huang also highlights quality concerns and instances where dubious events disguise themselves as legitimate festivals but primarily function as marketing campaigns, lacking genuine focus on films or qualified judging criteria.

“It’s beneficial to have additional screenings as they stimulate filmmakers to produce more works. However, some of these events lack quality control and feature unqualified judges, which can mislead filmmakers,” he says. He once came across a “fake” film festival staged solely as a one-time promotional event for a new real estate development.

Still, filmmaker Huang Wenli plans to keep submitting and believes that targeting a niche market is a viable approach for festivals to sustain themselves. “I think the existence of these festivals is more about giving filmmakers opportunities to engage with audiences and receive direct and tangible feedback for their films,” he says. “And if you are shortlisted for a prominent film festival, there’s a chance that you may break into the mainstream.”

Wang is optimistic about the future of independent film festivals: “Even if independent film festivals struggle to survive or grow in China, the culture of cinephiles and independent film festivals endure. Film screenings, exhibitions, and events will continue to emerge.”