In a year marked by a competitive job market and viral trends, here are the words and phrases that netizens coined to talk about it all

With the end of the three-year Covid-19 lockdowns and restrictions, the year 2023 has proven to be a vibrant and dynamic one, as people can finally embrace their normal lives—only at a faster pace.

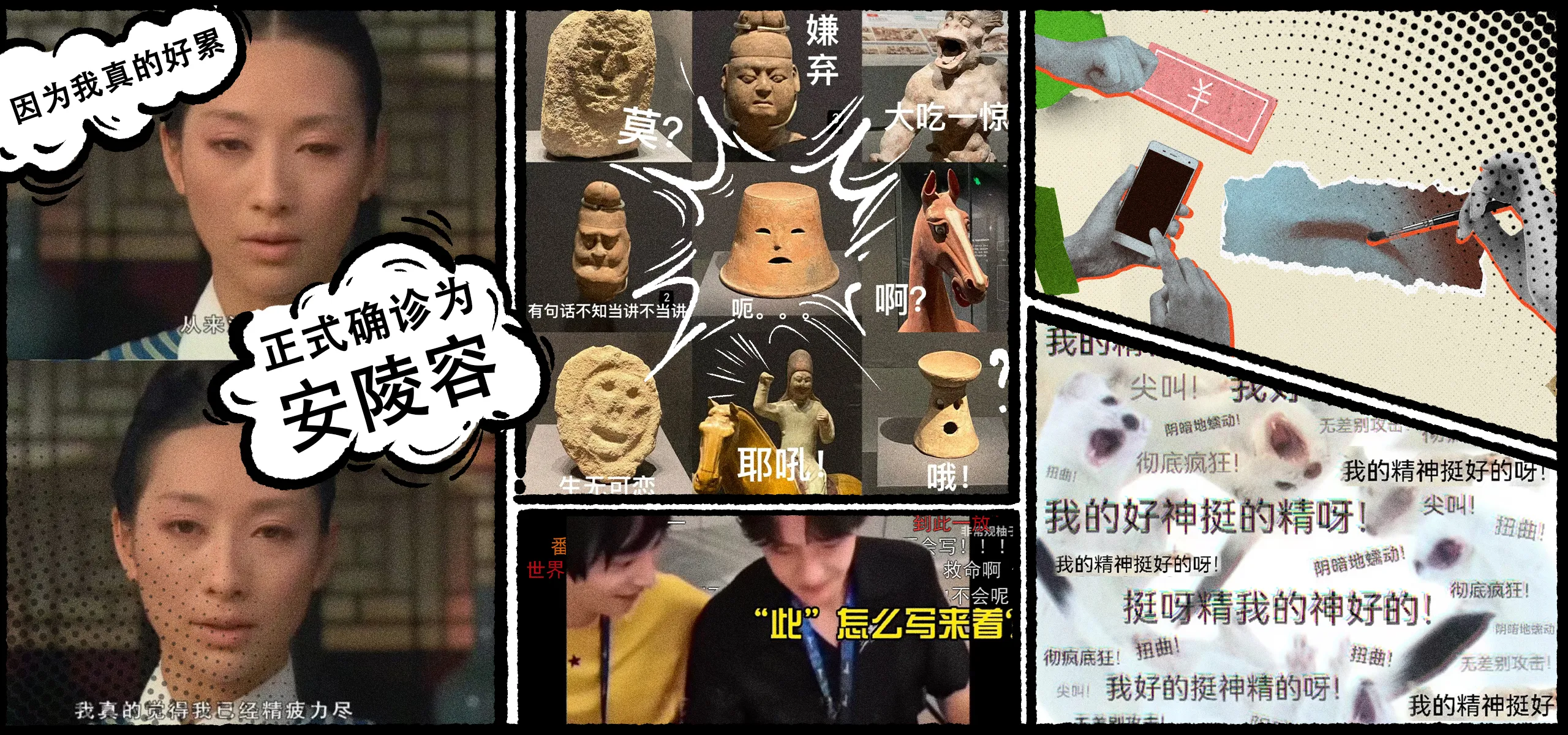

As we reflect on the year, it’s impossible to ignore the cultural zeitgeist captured through the lens of memes and slang. These expressions not only provided comic relief but also a unique insight into the societal shifts and even economic trends that shaped the year. Here are some that caught TWOC’s eye in 2023.