More over-35s are escaping the rat race in China to study abroad, but meeting challenges integrating too

Wang Lu popped the cork of a long-treasured bottle of red wine when the fifth offer from a list of prestigious British and American universities came in. Getting into these schools at the age of 43 felt like an encore of his teenage years.

Wang had spent nearly two decades gradually advancing from an entry-level programmer to the senior IT director at a well-known internet company before his whole team was laid off for failing to meet profit expectations. “My mind went totally blank,” he recalls.

Wang hoped to climb his way back to a similar position. However, recruitment websites placed an age cap for senior roles in his industry at 40. Out of desperation, he started applying all over the place. “I submitted my resume to over a hundred companies. I didn’t really look into many of them. My priority was finding a new job as soon as possible.”

Five of those companies called him for an interview. Wang Lu had hoped that a new haircut and a shave would appease his interviewers’ fixation with age, but he was vexed to find this was not the case. “They were looking for young professionals with extensive experience. How is that possible?”

The seniority that had once earned Wang accolades and respect was now hurting his prospects in the job market. He was haunted by frustration and going through a midlife crisis until he came across people who were dealing with the same struggle on social media. Many of them had got a fresh start as international students overseas.

Wang had a dream to study abroad when he was younger but ultimately gave up the offer. Twenty years later, a renewed desire had ignited in his heart. This time, Wang was determined to go.

A shortcut out of a midlife crisis?

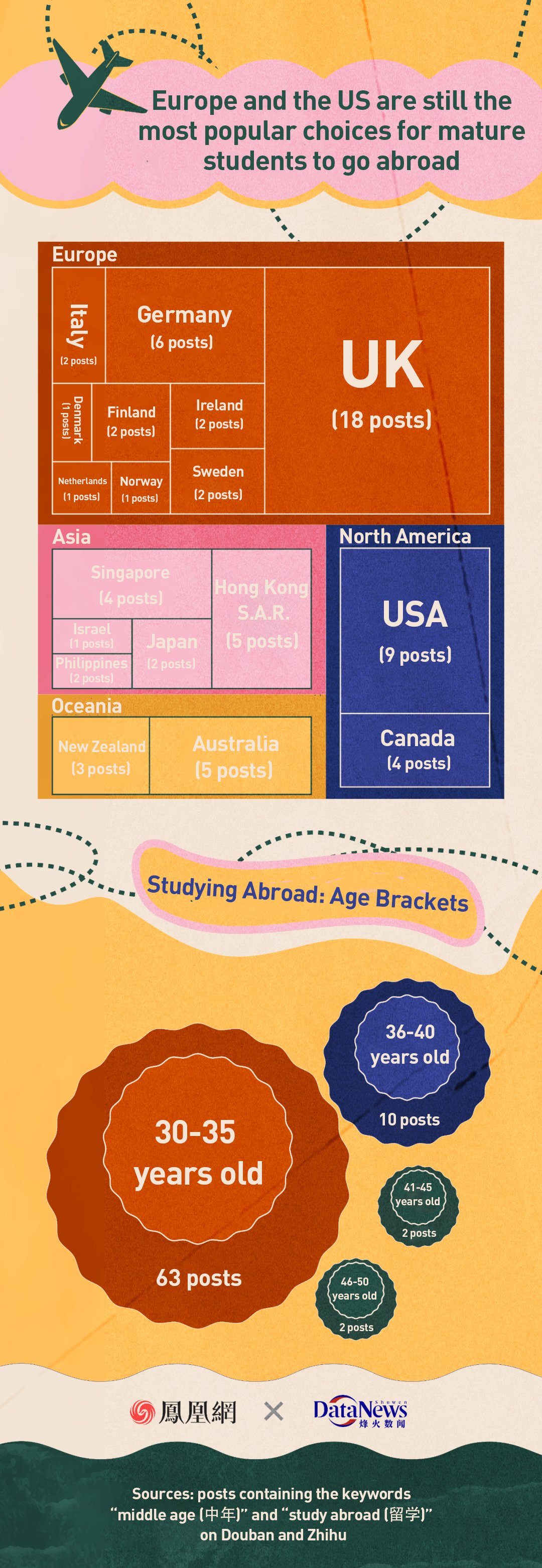

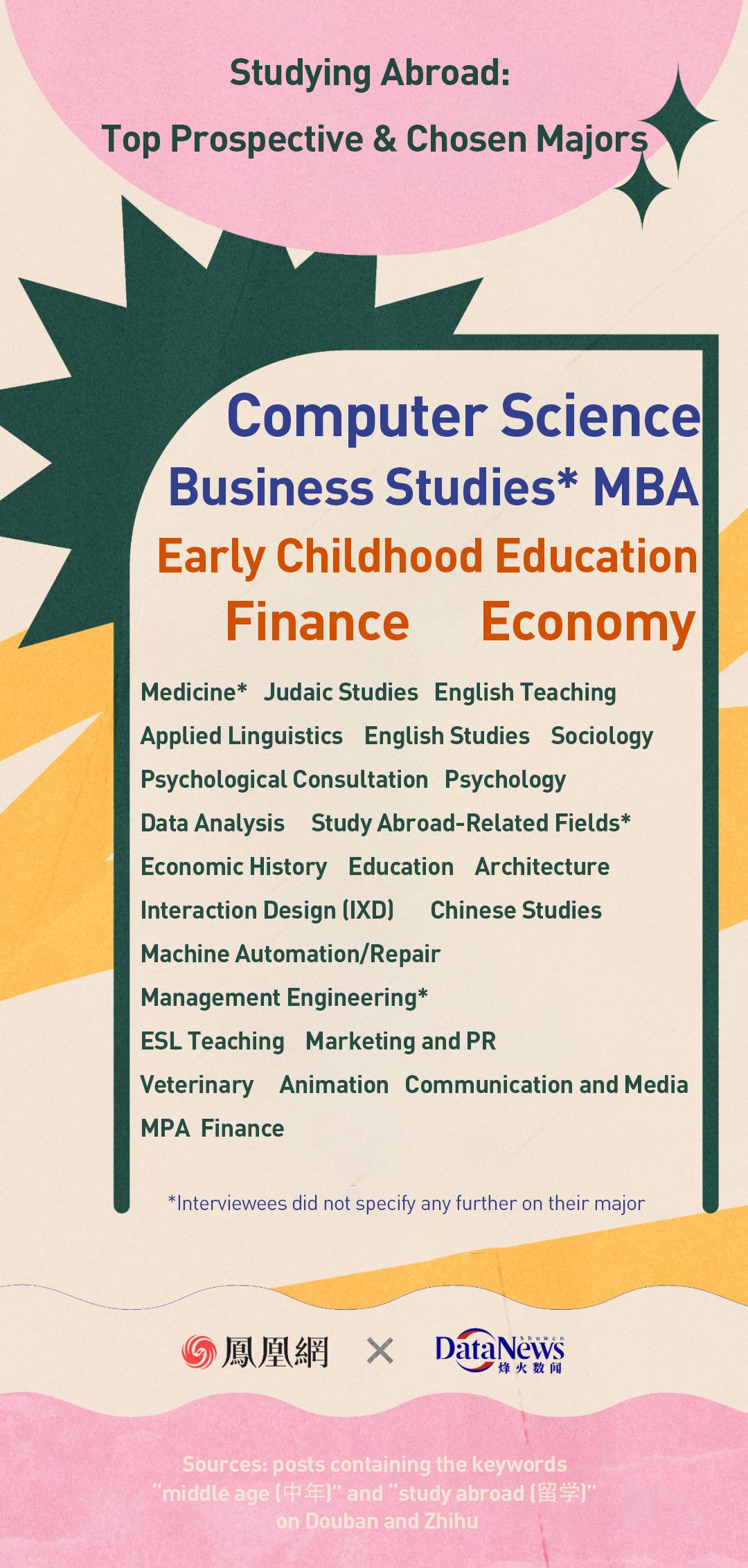

Wang is just one example of a growing trend in recent years—an increasing number of middle-aged Chinese people are defying societal norms by pursuing further education overseas. After reviewing 2,216 related posts on discussion forums Zhihu and Douban, our reporters found 93 posts that correspond to this demographic of older individuals seeking to study abroad. More than 90 percent of these individuals chose to go abroad due to anxieties related to age and challenges in switching or advancing their careers.

Wang Zhenyong (no relation to Wang Lu) resigned from his job in procurement management at a state-owned electric power company because he felt his career had become stuck. “My days were seemingly ruled by this pre-written script where I was sandwiched between the old bigwigs, all comfortable at the top, and the ever-struggling youth who are desperately vying for promotions,” says Wang Zhenyong. When he saw his friend boasting about a charmed student life in the UK on social media, the 35-year-old couldn’t help but feel a twinge of jealousy. “That’s how I started to envision a different life for myself. Maybe I could have a fun time, sipping on afternoon tea in London and chatting up people from all over the world.”

Besides facing career bottlenecks, external stimuli also serve as reasons for over-35s to explore a life outside their home country. As people born after 1995, a demographic most likely to have overseas education, begin to enter China’s workforce, their broad perspectives and learning capabilities have stirred a sense of urgency among older people. Many share that younger returning international students are competent, creative, and exhibit greater confidence in their work. They also approach challenges with unexpected solutions. The generational gap is exemplified by the recent surge of AI technology in offices, which is often spearheaded by younger employees who have long ditched the outdated written sources to which their older colleagues cling.

Though the job market is sluggish, international students still enjoy better and more job opportunities than domestic graduates. Statistics from the 2022 Blue Book on Returned Overseas Chinese Graduates and Employment, a report published by the Ministry of Education, reveal that over half of international returnees in 2021 gained employment in Beijing, with nearly 50 percent of them landing jobs in state-owned enterprises.

Studying abroad may seem like an immature adventure, but for many seasoned professionals facing a stagnant career, it is worth taking a leap of faith when they still have the will and energy. This might be the fastest route out of their current situation. After all, the vast majority of those surveyed feel the latest possible time for a fresh start abroad is the first half of their thirties. Europe and the US still top the chart of potential destinations as most of the schools there don’t require applicants to learn a new language other than English.

Li Huiwen, a 37-year-old single woman, still has vivid memories of the shock in her friend and family circles when she ditched her cushy job in the consumer goods industry in Shanghai and moved to the UK to study drama.

Li didn’t want to continue her everyday office life—trapped in a cubicle, day after day, facing sales data and endless meetings. She has always been passionate about art, literature, and theater. When she was younger, she yielded to family pressure and chose to major in marketing in college, which promised better career opportunities. Even when she worked in Shanghai, Li still found time in her busy schedule to visit museums and other cultural venues. Her antidote to regular overtime was late-night reruns of her favorite films at home.

Fortunately, Li has always been a firm believer in blazing her own path. Fresh out of college, she turned down the stable job that her parents had secured for her through connections in their hometown, a small county in Northwestern China, to start an independent life in Shanghai. Her coming of age in the big city was bumpy: she was scammed during the job hunt and was once kicked out of her apartment in the middle of the night by her landlord. However, life in Shanghai also broadened her horizons, shaping who she is today.

“For the longest time, I could not go after the life I’ve always envisioned for myself. Now that I’ve had more experience and savings, there’s no reason to give up,” she says.

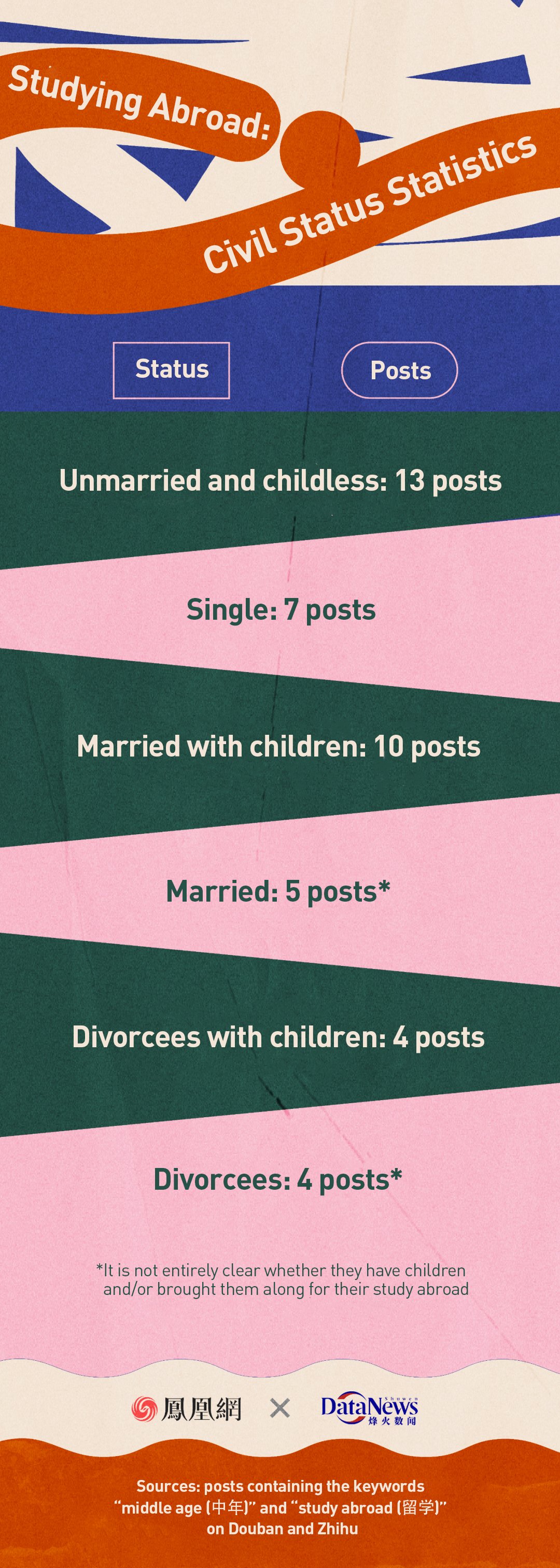

However, Li is an outlier among women in her age bracket: single, childless, and financially independent. When she posted her experience on social media, it was met with envy and admiration from netizens. Among the group of older students who studied abroad we interviewed, the majority are single, but many married people also bravely set out on their own.

Li is resolute about her current lifestyle: “Money, promotions...There’s no use to any of that if I’m stuck in a job I don’t love. A car and a house are all I need for a stable life. I just want the freedom to do as I please.”

Everything is harder than I imagined

Deciding to study abroad is the simplest step in the entire process. After that, people have to apply, take exams, and then get used to being a student again in a foreign land—that’s when the true flavor of studying abroad becomes a reality.

Wang Lu had an outstanding resume and a clear goal in mind: improving his expertise in the field. With few hiccups, he quickly received admission to the Information Technology program at Columbia University, a prestigious Ivy League school in the US. He engaged in academic discussions with the faculty there and visited Silicon Valley to see the latest technologies. Now graduated, he still often hangs out with his old classmates and friends, many of whom have settled in the US. Overall, he feels revived by the endeavor: “When you water a plant after a long dry spell, it thrives. Well, I flourished at Columbia. It really was the most fulfilling period of my life.”

However, Wang Lu is privileged in his clear-minded, adaptable approach to life abroad. Not everyone returned to school with such ease.

Wang Zhenyong regrets what he now considers a hasty decision to study abroad. “I had been out of school for two decades. My English was so rusty that it took me four attempts to scrape a pass in my IELTS test [a standardized test for non-native English speakers].”

His struggle with English was only compounded when he started attending his university classes. The professors spoke too fast and his international classmates used a mosaic of accents. Wang Zhenyong’s hard-earned IELTS score was nowhere near enough, and he cowered in embarrassment at lectures where he could neither follow the heated debates nor laugh at jokes.

The high cost of living in the UK also sapped his energy. Every day was a struggle to save money. “Everything is just so expensive. Your rent, your groceries, even your bus ride. When it comes to entertainment, all I could afford was watching TV dramas at home and talking to my friends in China,” he says.

Wang Zhenyong feels like a lonely fish out of water in the UK, where he often experiences a culture clash. “Back home in China, I am well acquainted with our culture and its subtleties. Here, I can’t tell a polite greeting from a heartfelt word. We have completely different ways of thinking,” he says.

Faced with these prospects, Wang Zhenyong sometimes stays up late in his rented apartment and browses Chinese recruitment websites. “I’m not scared that other people would see [me browsing these sites], but I’m hiding from the ambition I had before coming to study abroad. You know, maybe I’m meant to be sipping tea at a comfortable office job. I have a hard time talking about this with family and friends. I want to keep them in the dark because embellishing my reality with pretty lies [about life here] will make me regret my choice even more,” he says.

Integration is a big issue for students abroad. That’s perhaps why most of the older students who graduated successfully had some relevant overseas experience before their studies. Whether they had been students, seasoned travelers, or worked at international companies, their background helped them integrate into a foreign society.

Many also find the programs at overseas schools more demanding than they expected. Language issues compound the already intense struggle with coursework that these mature students struggle to complete. For many of them, catching up on their academics proves no easier than holding a full-time job.

The age gap in the classroom can be another issue. Mature students may struggle to work together with their younger peers, who are once again all too eager in their use of the latest technologies like ChatGPT.

However, some mature students we interviewed did feel that these interactions presented them with a chance for growth. “To me, younger people used to be mere subordinates. Now, I treat our time together in class as an opportunity to develop my creative skills and learn from them. Hopefully, that’ll prove useful in any future work,” one person we talked to for this piece told us.

Can studying abroad change your life?

Wu Di, a graduate from an Australian university, shared a piece of wisdom in his WeChat moments on the day he received his diploma: “It’s your vision and skills that are holding you back, not your age. As long as you believe it’s the right thing to do, you can keep doing it.”

This confidence didn’t come easily to him. Initially, Wu also feared that he had made a rash decision. His mentor, a lecturer at the university, assuaged his fears: “You know, people should always be able to choose whatever feels right for them,” Wu remembers him saying.

His mentor was well into his sixties, yet remained full of energy and knowledgeable about youth trends. Recalling his zest, Wu now reflects: “Age really is nothing but a number. A person’s value comes across through their ability to always grow and absorb new knowledge. As an older professional, I have better foresight and sharper judgment, not to mention my extra experience. Those like me have much to offer in terms of their unique strengths, whatever their path is in life.”

Many of these mature students have been labeled as “going against the social clock,” but according to the data we found and interviews we conducted, most of them believe the experience has changed their way of thinking and eased their anxiety around age. From the 93 posts we analyzed, 35 percent mentioned feeling “more confident and cheerful,” and 18 percent said a degree from overseas helped them find their dream job.

Many of these mature students greatly benefitted from gaining contact with industry leaders and experts. Interacting with people from different cultural backgrounds has also broadened their horizons and enhanced their thinking skills—invaluable assets in the workplace.

However, this is not to say that everyone will find a suitable position in China. Li Huiwen knows that at her age, with a diploma in drama but no sizeable related work experience under her belt, her chances of landing a satisfactory job are slim. But she isn’t stressed about it.

“Honestly, the whole point of studying abroad is to discover your original purpose. I found mine, so who cares if I am on the stage, pulling up the curtains, or taking notes backstage? Everything’s good as long as I enjoy it,” she says.

Written by Zheng Qin (郑钦)

Edited in Chinese by Fang Yuan (方远)

This article originally appeared in Chinese in Zairenjian Living. It has been translated, edited, and reprinted with permission.