From paper and straw to fur coats...this is what ancient Chinese wore to keep themselves warm in winter

Chinese military coats, a staple style in the 1980s and ’90s, have made an unexpected comeback in fashion among young people this winter. A short video featuring several college students in Shenyang, Liaoning province, wearing thick army coats, went viral on the social media platform Douyin (China’s version of TikTok) this November, accumulating over 2 million views. With their never-changing plain design and dark green color, the coats have surprisingly threatened the popularity of modern (and much more expensive) down jackets that have dominated the Chinese winter wear market for years.

According to Moojing Market Intelligence, a Beijing tech company specializing in e-commerce data analysis, the average price of downcoats in China exceeded 1,200 yuan between November 2022 and October 2023. Meanwhile, a military coat generally costs from around 50 to 200 yuan. With many young people purchasing more rationally than they used to, the coats are enjoying a boom.

But while these long cotton military coats have kept Chinese people warm for decades, they came along far too late for ancient people who relied on furs, animal skins, and paper to keep themselves warm in winter.

Cotton wasn’t commonly grown or used for clothing until the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644). Long before that, during the first millennium BCE, fur coats—known as qiu (裘)—were the main winter clothes. As Han Feizi (《韩非子》), a book by the 2nd century BCE legalist Han Fei (韩非) and his followers, records: “Wear deerskin fur coats in the winter, and clothes made of Chinese arrowroot in the summer.”

People wore many different furs in the past. According to the History of the Great Jin Dynasty (《大金国志》), a 13th-century book on the Jurchen-led empire, “rich people used fur of marten, fox, raccoon dog, and lamb, sometimes with silk fabric as sleeves…the poor used that of fox, horse, pigs…or even skin of fish and snakes.”

Before that, as early as the Shang (1600 – 1046 BCE) and Zhou (1046 – 256 BCE) dynasties, common folk mostly made clothes out of hemp or ramie, a nettle-like plant. To stay warm during winter, they would insulate themselves by stuffing oakum and the dried flowers of reeds between two pieces of hemp or ramie clothes. Accordingly, the term 布衣 (“cloth gown”), another name for the cloth of ramie fiber, has referred to “common people” for much of the country’s history.

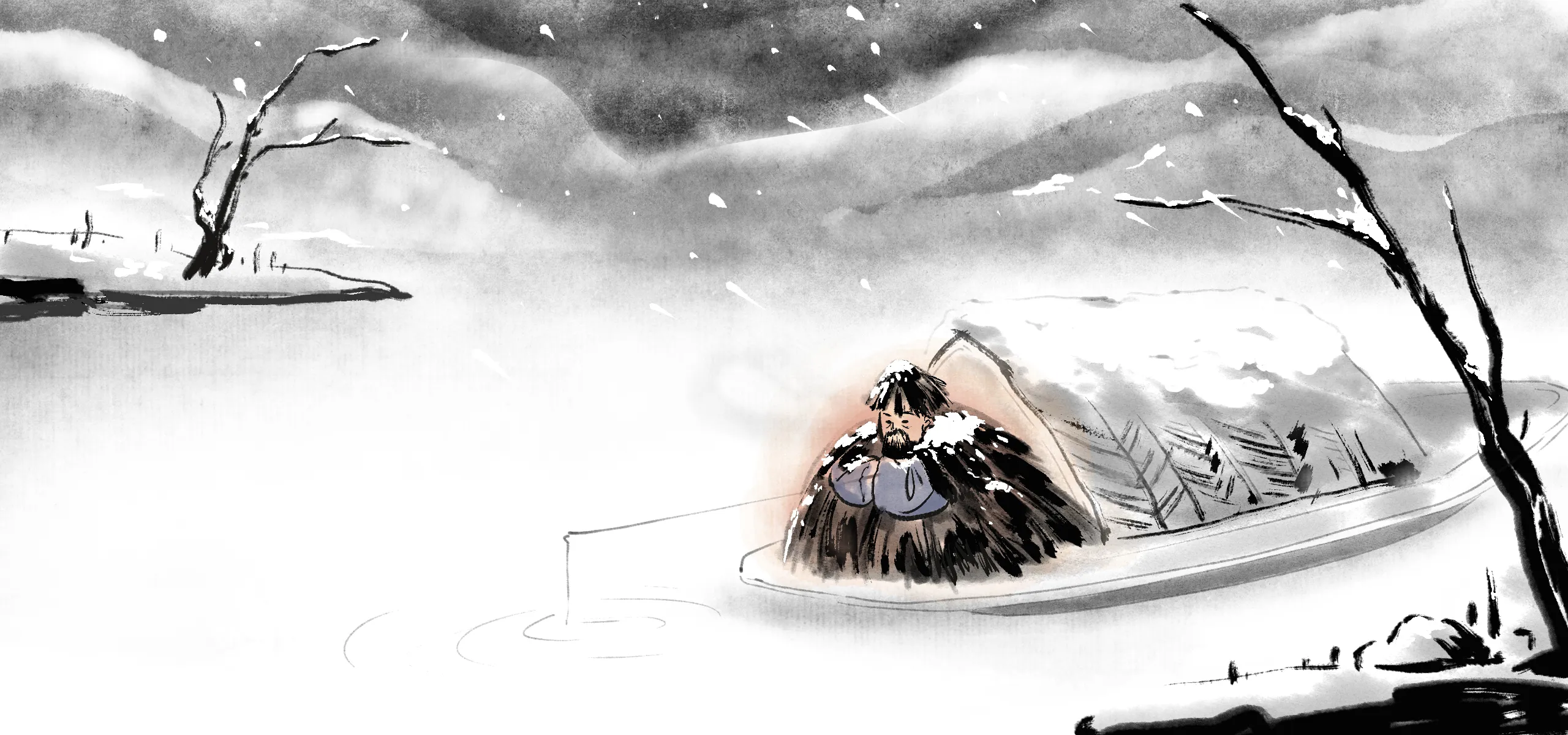

During the Zhou period, the poor resorted to suoyi (蓑衣) coats, originally crafted from the Chinese alpine rush, as a means of staying warm. Later, a more advanced suoyi, made from woven palm fiber, gained popularity across all social classes for its windproof, waterproof, and insulating properties. The famous Tang official and poet Liu Zongyuan (柳宗元) wrote in his work “The Snowbound River”: “In a lone boat on the snowbound river, an old man, in palm-back cape and straw hat, drops his angle string.” Even in the classic novel Dream of the Red Chamber (《红楼梦》) from the Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911), characters from wealthy and noble families, such as Jia Baoyu, favored suoyi on rainy and snowy days.

For those who couldn’t even afford the suoyi, paper coats were a popular alternative for their low price. First appearing in the turbulent Wei and Jin dynasties (220 – 420), when ramie fabric became scarce due to frequent wars between different powers, the paper coats—mainly crafted by boiling, processing, and pressing the bark of paper mulberry or rattan—were inexpensive, thick, pliable, and allowed for mending once worn out. During the Tang (618 – 907) and Song (960 – 1279) dynasties, the material got popular among commoners, monks, and even some literati as well.

Renowned Song scholar Lu You (陆游) wrote in his poem “Work on a Cold Rainy Day”: “[I’ve] swept the garden, collected the leaves, and dug the ground to build a clay stove. Luckily, I have Chenopodium to cook with porridge; and there is no need to be ashamed of wearing a paper jacket.” The material was also used to make quilts and even armor for soldiers.

The use of paper cloth gradually declined and vanished as cotton became more accessible. This shift was facilitated by the government’s promotion of cotton cultivation nationwide and advancements in cotton textile technologies driven by individuals like the “mother of Chinese textiles,” Huang Daopo (黄道婆), during the 13th century.

But some of these ancient materials and clothes might make a comeback in the future, just as army coats unexpectedly came into fashion this winter. As some Chinese netizens have noted on Weibo recently: “Fashion trends are cyclical.”