She led an army of women against Qing forces, fought her whole life for women’s rights, and even slapped the country’s top leaders for failing to commit to gender equality—meet Tang Qunying

August 25, 1912, was a historic day. Revolution had just swept away 2,000 years of imperial rule, and China’s leaders gathered in Beijing for the founding conference of the Kuomintang—the country’s new ruling party.

It was also the day a group of firebrand women, themselves revolutionaries who had helped bring down the Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911), stood up for their rights. In front of Sun Yat-sen, Song Jiaoren, and other household revolutionary names, they made their call for equal rights heard in dramatic fashion.

As Song, co-founder of the party, began a speech, several women stormed the stage. One of them slapped Song across the face. When Lin Sen, another party leader, emerged to mediate, he got slapped too for his troubles. The assembly soon descended into chaos.

The chief instigator of the protest was Tang Qunying (唐群英). She had played a key role in toppling the Qing government as a member of the Chinese United League, a forerunner to the Kuomintang founded by Sun and other revolutionaries, and had led troops in battle against Qing forces. But she was dismayed that the newly formed Republic of China was about to row back on its promises of equality for women, removing the assertion that all citizens were equal regardless of gender from Kuomintang’s guiding principles.

Tang’s protest brought China’s nascent women’s rights movement to the forefront of national politics. But for Tang, it was just one of the countless struggles this early feminist hero faced against inequality in the late Qing and Republican Era (1912 – 1949). She led troops against Qing armies, established some of the country’s first newspapers dedicated to women’s issues, and built schools for girls. She remains one of China’s most influential early feminists.

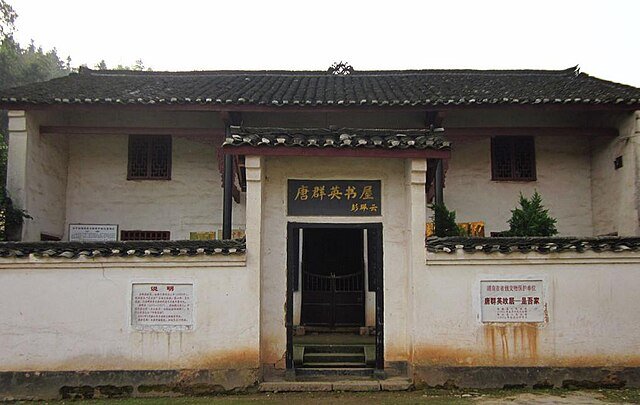

Born in Hunan province in 1871, Tang was the daughter of a Qing dynasty military general. As a child, she learned swordsmanship from her father while refusing to have her feet bound—a centuries-long tradition meant to shape and limit the size of young girls’ feet. She repeatedly unwrapped the cloth her mother put around her feet.

In 1891, Tang married a cousin of Zeng Guofan (曾国藩), a famous statesman and military general. Zeng was distantly related to Qiu Jin (秋瑾), another woman who would become a famous revolutionary and feminist, and the two female activists soon became close.

When Tang’s husband died a few years later, Tang rebelled again. She ignored the custom that a widow stays with her husband’s family and returned to her hometown determined to start a new life. She read extensively, absorbing new ideas circulating in China at the time about how to reform the country, from the prospects for democracy to questioning the divine right of the emperor to rule.

In 1904, Tang went to Japan to study. A year later, she became the first female member of the Society of the Revival of China, a revolutionary association established with the goal of overthrowing the Qing and establishing a democratic and free country.

When the Society of the Revival of China merged with Sun Yat-Sen’s Society for Regenerating China to form the Chinese United League, Tang became its inaugural female member. The organization eventually became the government-in-waiting after the Qing fell. She paved the way for another 20 or so women to join the league in the coming years.

By 1908, Tang was back in China actively promoting rebellion against the Qing government. When the Wuchang Uprising began in October 1911, Tang, a warrior since she learned how to wield a sword in her youth, cobbled together an army of women to join the battle against the Qing forces. In November, Tang led 400 women to assist in the capture of Nanjing, Jiangsu province, from the Qing government.

For her role in toppling the Qing regime, Sun, now the provisional president of the newly declared Republic of China, praised Tang as a “heroine and a founder of the Republic.”

However, this only marked the beginning of Tang’s work for a more just and equal society. Amidst rumblings that a new constitution might not include commitments to women’s rights or even gender equality, Tang founded the Women’s Suffrage Alliance to lobby for women’s rights to vote and run for office in the new government. The alliance also called for an end to the sale of women as maidservants and slaves, making polygamy illegal, and forcing an end to foot binding.

“Now the political revolution is complete, a social revolution will follow. To avoid chaos in the social revolution, social equality must be a top priority. To achieve social equality, gender equality must be a top priority. To achieve gender equality, women must be granted suffrage,” Tang wrote to the provisional assembly.

After the provisional constitution was enacted in March without any mention of women’s suffrage, Tang organized more protests. Around 30 armed representatives of the Women’s Suffrage Alliance stormed the assembly and smashed windows. But new electoral laws implemented in August specifically excluded women from voting or standing as candidates. Enraged by this development, Tang organized the aforementioned protest at the Kuomintang’s founding conference the same month.

Though he remained sympathetic to Tang’s cause, Sun offered little encouragement. He wrote to Tang explaining that most men wanted to delete the gender equality clause so confronting two representatives at the meeting was meaningless. “Only if you don’t rely on men to act on your behalf can you avoid being used by men,” Sun told Tang.

Tang heeded his advice and continued the fight. To achieve suffrage women needed to strive for two things: “One is that we need to have the knowledge to participate in political affairs, another is that we should have the ability to make a living independently. Both of these things come from education,” she told members of the Women’s Suffrage Alliance during the opening of its new headquarters in Beijing.

Tang established newspapers with the goal of educating women on public affairs. In 1913, she started the Women’s Rights Daily, Hunan’s first newspaper dedicated to women’s rights. She also established the Vernacular Newspaper for Women, which, according to its code of practice, aimed “to popularize knowledge about women’s issues. We use simple language to tell the truth, striving to achieve the goal of gender equality.”

However, the democratic government promised during the revolution was soon dismantled. By 1913, Yuan Shikai had been appointed president. After Tang publicly criticized his increasingly autocratic rule in her newspapers, Yuan ordered her arrest, along with the closure of the Vernacular Newspaper for Women and Women’s Suffrage Alliance. Tang fled to the south of the country, away from Yuan’s power base in Beijing.

Unloved by the new regime and having spent most of her money on advocacy, Tang lived the rest of her life in relative poverty. She died in her hometown in 1937 at the age of 66.

But her legacy lived on. From 1912 to 1930, Tang established around 10 schools for girls in Beijing and Hunan, providing them with education so that they could live with more freedom.

By 1916, Yuan (who had briefly restored imperial rule after declaring himself emperor) was dead. Despite the proceeding decades of republican rule characterized by a fractured country and war, the 1947 Constitution of the Republic of China stated that all citizens, regardless of gender, were equal before the law.

In 1949, when the Communist Party of China came to power, it also included a clause on gender equality in its constitution. Finally, in 1995, Tang gained greater global recognition when she was selected as one of the “eight outstanding Chinese women of the century” at the United Nations’ 4th World Conference on Women (held in China for the first and only time).

Though her status as a pioneer of China’s feminist movement is somewhat overshadowed by her friend Qiu Jin, who was executed by the Qing government in 1907, Tang’s place as a pioneering feminist in early 20th-century China is undisputed. Few fought harder for women’s rights and education, and even fewer still had the boldness and status to get away with slapping revered revolutionaries on stage.