How poetry helped Han Shimei endure a loveless marriage and a lifetime of hardship in rural China

This story was originally published in podcast form by Story FM.

My heart cradles an orange light

Not quite fit for the warm spring sunshine

Only a wisp of plum fragrance lingers in the chilling wind

I knead it all, this hurt in my heart

into ten thousand rays of light

Aiming at the sun, the moon, and the stars

Rolling with the waves of the South China Sea

The pain dilutes into the lights of thousands of homes

Only the passing clouds linger

The sky is full of you.

—Han Shimei, “Orange in the Heart”

This is a poem written by Han Shimei, a 52-year-old woman born and raised in Nanyang, Henan province. Confined to her small, impoverished mountain village, Han speaks a local dialect and her world is narrow. Her days are spent caring for her husband, parents-in-law, and children, as well as tending to greasy stoves, rough farmland, and the family’s dilapidated house. Working by day and sighing her nights away, Han led a thankless, harsh life that is all too often the standard in China’s rural communities.

The only thing that set Han apart from other farmers was her love of poetry. In April 2020, this passion brought unexpected changes to her life. Encouraged by her son, Han began to share her poetry on social media through a series of short videos. Soon enough, she went viral. Her talent was recognized to the point that she was invited to give a speech at the United Nations headquarters in Beijing.

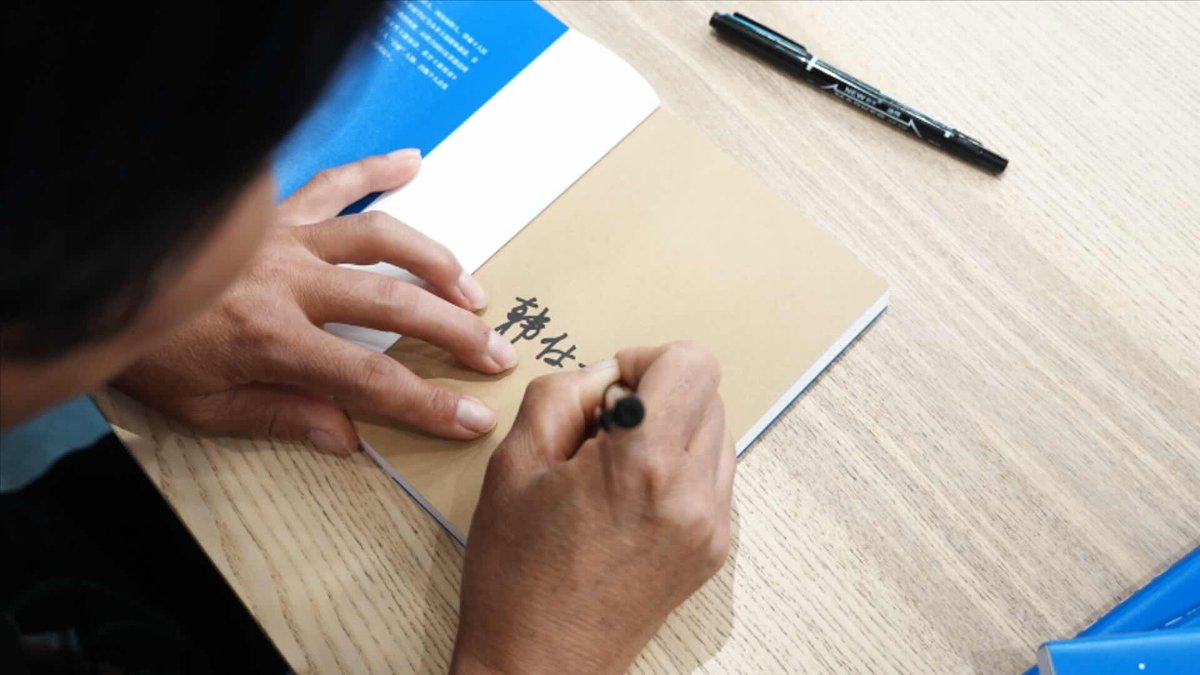

A call from a publishing house came in March 2022. Han’s personal poetry collection, The Waves Embrace Me, was finally released in September 2023. Her popularity stems in part from her undeniable talent, but also from her story as a lower-class rural woman challenging her fate with poetry as her weapon. Han wrote her body of work while leaning on her stove and recited them while walking across fields. Her crooked script was scribbled on her son’s unused notebooks and even cardboard from delivery boxes. Her poems are informed by her experiences of poverty and hunger, and used to decipher the loneliness and weariness of a fate that had always seemed inescapable.

About 80 percent of Han’s poems are about love. Love is a tangerine-hued warm light hidden in the darkness that has seized her heart over the years. Han writes while contemplating this orange glow flickering in her life, sometimes bright, sometimes dim. Her memories and prayers have transformed into poetic verses of romance.

Now, she’s known to her audience as the “poet on the ridge,” or the next Yu Xiuhua, one of the most popular female village poets. However, Han doesn’t really agree with these titles. She says she’s not Yu Xiuhua, nor does she write poems. She is just Han Shimei, and she writes mere doggerels.

Here’s Han’s story:

1

Small village dreams

I am but a small crow

How can I fly like a phoenix?

—By Han Shimei

Han Shimei: My name is Han Shimei. I was born on November 11, 1971. My family is originally from Hubei province but I now live in rural Nanyang, Henan province.

Born to a farming family, I was one of five children, and we grew up dirt poor. My parents were under a lot of pressure.

I recall that we grew lots of sweet potatoes in Henan every spring. My father would collect them in sacks and later grind them into a fine powder to make vermicelli noodles, a staple in our village. You could see them hanging to dry everywhere in our family room. I was tired of eating them, but it’s not like we had any other choice.

My father was a kind man who let my mother wear the pants in our house. So, for me, the saying that women hold up half the sky rings pretty true.

My mother had gone to school long enough that she could read, and so she expected me to learn, too. As a child, I had this dream that I would one day venture out into the world through education. I didn’t want to stay in the village. So I applied myself in my studies, and I was a very smart kid.

When I was in fifth grade, our class was asked to write an essay on the topic of perseverance. I remember vividly that the piece I wrote was called “The Bow-Tie Hairpin.”

The title was inspired by the trinket that my mother once bought in town to bribe my 13-year-old sister into helping with chores. I was very fond of it. In my essay, this beloved colorful hairpin was the prize atop an imaginary mountain that three girls raced each other to climb.

My teacher read the article to the whole class and sang my praise as the only student who had truly understood the assignment.

Unfortunately, my schooling was cut short during the second year of middle school. My family couldn’t afford the 18-yuan tuition fee for the second semester, and just like that, I was forced to drop out of school.

I did not want to leave school. For the next few years, I had recurring dreams of doing homework in the classroom I would never step foot back in.

Story FM: Han was 14 years old when that 18-yuan tuition fee woke her up from her dreams of leaving the village through education and rendered her already small world into an even narrower one. From that point on, she supplemented the family’s earnings by working in the field, knitting sweaters, making shoe soles, and pressing noodles. Leisure and recreation options are limited in rural areas. For the most part, men gather together to drink while women play cards. Han didn’t like these activities, so when she wasn’t working, she just spaced out.

Han wasn’t pleased with her life prospects, but she had no say.

One day, Han got a black box filled with books from her mother, a self-confessed bibliophile. She had retrieved them from her maiden home. Inside the box, Han found classics like The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Dream of the Red Chamber, Outlaws of the Marsh, and Journey to the West, as well as a bunch of martial art novels and ancient poetry collections.

Her mother’s gift opened up a vast world of imagination for Han, who became obsessed with reading. However, it was also her mother that caused her the most stress.

In her family, her mother’s decisions were final, including who her daughters would marry. When Han’s grandfather passed away, the family struggled to cover his burial costs. As a result, Han’s second eldest sister was married off in exchange for a 400 yuan bride price. Her third eldest sister was also married off for 1,600 yuan to finance the marriage of her big brother.

“She wasn’t marrying off her daughters but pawning them,” Han says.

She was keenly aware that her own day would come. However, just at that time, a chance came for the orange light of love that was hidden in her heart to light up.

2

Love and 3,000 yuan

Love

rolls in my blood

With a vast heart

I hold your hand tightly not to part

Together under a Bodhi tree,

we gaze at the moon

Eyes brighter than the stars

My tears of happiness well up in my blood

—“With You” by Han Shimei

Han: My mother was a positive force overall. However, as she had the final say on all things family, we couldn’t choose our own happiness.

Having arranged the marriages of all her four daughters but me, my mother once told my eldest sisters that I would be free to choose my own partner. I felt so happy! How lucky I was. My mind was filled with the words of Southern Song dynasty poet Lu You (陆游) for his sweetheart Tang Wan (唐婉) in “The Phoenix Hairpin.”

Pink hands so fine,

Gold-branded wine,

paints green willows palace walls cannot confine.

East wind unfair,

Happy times rare.

In my heart sad thoughts throng,

We’ve severed for years long.

Wrong, wrong, wrong!

Spring is as green,

In vain she’s lean,

Her silk scarf soak’d with tears and red with stains unclean.

Peach blossoms fall,

Near desert’d hall.

Our oath is still there, lo!

No word to her can go.

No, no, no!

(Translated by Xu Yuanzhong)

I envied the tragic love between Lu and Tang. Though they were cruelly separated by his mother and, ultimately, by the feudal code of ethics of their time, their unswerving affection was forever etched onto my heart.

I used to believe that I, too, could have a story like this, as long as I met my true love. I can’t say I had any childhood sweethearts. I wasn’t chatty to boys in school, and it was only as I grew into my young adult years that I longed for this kind of durable, lifelong happiness that I thought I would find next to a loving husband that I could dote upon. In return, my husband would love and care for me, too.

Story FM: Han was nineteen when she finally met her husband.

But then, the orange light went out.

Her family needed to build a new house, and her younger brother was about to tie the knot. In short, they needed money.

Han: I was 19 years old when my mother arranged my marriage. I had no say in it. His name was Wang Zhongming.

I met him in town first. Looks wise he was alright, but his gruff voice made it quite hard for me to decipher his already poor speech. I was certain I didn’t like him from the beginning. Then again, if I ever had the choice, I wouldn’t have dropped out of school either.

I stated openly that I did not want to marry Wang. Mother just took me home and scolded me. “An ugly duckling like you can’t afford to be picky. Stop causing me trouble!” That was the end of my resistance. No more opinions allowed. The marriage talks were finalized and I was “sold” for 3,000 yuan. A third of that sum, my mother set apart to build the new family house. The remainder was spent on household things.

I tried to warn my mother, I really did. Back then, ordinary families like ours could never cough up thousands of yuan for marriage. Only a man struggling to find a bride would offer that kind of money. “You’re like a garbage collector! You pick up what others don’t want and make him your son-in-law!”

Three years into our engagement, I still refused to see Wang whenever he came to our house. I just didn’t want anything to do with him.

I drowned my sorrow in alcohol during that time. I was a teetotaler until then. Whenever I got drunk, I would cover a water tank by the door of our house with a lid, and cry with my head and arms resting on it. I cried a lot.

I felt that this was not what I wanted for my life, and came to dread my eventual wedding.

On that fateful day, a large military truck came to pick me up. This was my wedding car, and I stood by my bed bawling. A woman from the village told me to cut it. “Your father is crying too,” she said.

So I wiped my tears, got in the truck, and left.

The wind carries a lonely song

for this dark night,

when the light in my heart

still flickers.

Mother’s hand reaches into my pitiful flesh,

ripping the light

away from my insides.

—“Nocturnes” by Han Shimei

Han: Just like that, I married into Wang Zhongming’s family in quite a daze.

I tried to convince myself to go with the flow. I just hoped that Wang would cherish me and be willing to live a good life by my side.

But this was no fairy tale. For starters, his family seemed to be even poorer than mine. They only had two dilapidated houses with tiled roofs. The ceilings were so low that I hit my head every time I went by the kitchen, to the point that I got several large bumps.

Soon enough, I learned that Wang had actually borrowed the 3,000 yuan from his uncle. I was now indebted for the full amount plus interest; a total of 4,800 yuan.

I had in fact bought myself with my own money.

When I first got married, I learned that our fellow villagers had a nickname for my husband. Wang’s reputation as a good-for-nothing person that could neither make money nor be helpful around the house, let alone care about others, had earned him the moniker of Hula Tang (胡辣汤, literally “pepper spicy soup”). Namely, a fool. I couldn’t possibly find a way to communicate with him.

We built a house with a total area of over 500 square meters, and construction cost a little over 50,000 yuan. Wang declared that we should pay the workers “3,000 yuan tops. No way we’ll shell out tens of thousands.”

I tried to reason with him. “Well, are you willing to work for free yourself? Those workers aren’t here to do us a favor, they’re here to work, earn their wages, and support their families. You owe them their due.” But he wouldn’t listen.

That day I waited until he went to work to pay the workers; about 20,000 yuan. When Wang got off work and found out, he was fuming. He gave me the cold shoulder treatment for a long while afterward.

Story FM: For the longest time in her marriage, Han made a point of avoiding everything that she couldn’t reason with her husband. In fact, soon after she got married, Han not only took on the responsibility of a wife and a mother, but even of a husband by supporting the entire family on her own. Wang was indeed rather useless, never learning how to cook or do his laundry. Han had to nanny him in every single aspect.

That year, she worked in a garment factory from 7:30 a.m. to 9:30 p.m., except when the factory was working to a tight deadline that required workers to stay until midnight. Han had to stand by the production line for her entire shift and was exhausted by the time she arrived home. However, she didn’t get to rest there. Wang relied on her for his meals and would have starved without Han slaving over the stove.

Han regarded Wang as a man-child. She was his wife just as much as she was his mother.

The one thing Wang could manage was hair-cutting, and he actually took over the hairdressing business for a production team (a farming unit in China before the economic reforms in the 80s) in the village, or at least that’s what he told his wife. Han never quite knew how many people were on the team, nor Wang’s supposed yearly income.

In any case, he gambled away most of the family’s money.

Han: I remember this incident back in 1994 when our son was a year old. We’d just finished dinner; it was the night of the fourteenth day of the twelfth lunar month. Wang told us both to go to bed before locking the door from the outside so that our son and I couldn’t get out of the house. Wang leaned on the windowsill and said “My brother asked me to go to their house and help them carry the cattle trough.”

He came back at dawn, freezing from his nightly escapade.

Just a couple of days later, a close neighbor came to our house. “I’ve got something to tell you.” He wanted to say something but eventually swallowed his words. He hemmed and hawed by our entrance when he was about to leave. “Do you know where Wang Zhongming was that night? He was gambling and lost over 180 yuan,” he said.

That was a lot of money for our small family.

When Wang came back in the evening, I asked him about his whereabouts that night, but he wouldn’t tell me.

I only came to learn about his vice later. He gambled hard and never won. From 1992, when we got married, to 2007, I kept settling his gambling debt. Once, I even had to face three creditors in a single day.

So, I had to go find jobs hard enough to pay well. There are precious few occupations for women in our village, so most of what I did was typically considered to be a man’s job. I couldn’t have cared less. In my mind, I could do anything as long as I made enough money to make our family rich and afford an education for my children.

To create a new world,

Myself I hurled.

Oar in hand, through the waves,

through a road-less mountain ridge that no man braves.

I created a new world.

I planted a spring

I planted joy, sadness, and pain.

—“The Creation of Heaven and Earth” by Han Shimei.

Han: For a while, I worked tying and folding steel bars on the highway. I was pretty good at it as the only woman in an all-male team. My arms were so tired from all that lifting. The pain hasn’t subsided since then.

In any case, our boss and his wife were pretty happy with my skills, and they even raised my salary from 50 yuan to 60 yuan. That was still well below my male coworkers who made 80 yuan a day. I had conflicting feelings. On one hand, I felt very honored by their acknowledgment of my ability. On the other hand, I couldn’t help but feel that I was still a bit short-changed, seeing as I was doing just as much as the guys on the team. I stayed there for half a year and made 8,000 to 9,000 yuan.

Story FM: In addition to her labor at the highway, Han also cooked in canteens and later joined the assembly lines of clothing and luggage factories. There, she was initially kept away from the fabric-cutting machine because it was deemed too dangerous for female operators. Han was hell-bent on making extra money and pestered the manager until he had no choice but to teach her how to operate the machine. To his surprise, Han mastered the whole thing right away without ever making a mistake. She could handle all the calculations to cut each of the 124 pieces of fabric needed to sew a backpack in the most cost-effective way. In the end, she earned the appreciation of the factory director.

However, Han paid her own price of sorts for all this hard labor. The long shifts standing up damaged her knees badly. However, she never got a single word of concern about her well-being from her family.

Han: It’s not like I had any choice. With the burden of the whole family on my shoulders, I couldn’t afford to care about gender roles. I had to be strong to support my household.

In 2002, we borrowed money from loan sharks in the village. That year, I went to work in the fields, pregnant with my daughter. The woman next door tried to talk me out of planting sesame seeds that year. “With a baby due this year, you want corn crops. Hoe them and you’re done.” She wasn’t wrong; sesame is more expensive and labor-intensive. But I still went with it, because I needed to repay our debt with the loan sharks.

Towards the end of my pregnancy, it was really tough for me to work the land. Going to work after breakfast made your eyeballs swell under the strain. I opted to skip breakfast to at least feel a little better.

One day, I heard the voice of our neighbor’s daughter in the busy fields. “Sister-in-law, you look so tired, working every morning on an empty belly. I brought you these two melons. Have some.”

I couldn’t remember the last time anybody in my life had shown care or affection towards me. I was so moved, I burst into tears.

I’m not too sure how I managed to survive that period. We had these plans to build a new family house, but more often than not, Wang made me really angry. I had dug this trench to eventually lay the foundations, and then he said it was too deep. We argued, and Wang ended up slapping me in the face.

Let me tell you, that was a defining moment for me. It was as though someone had poured a bucket of ice-cold water onto my heart and soaked me down to my heels. It finally dawned on me that Wang, my husband, only saw me as a tool at his service.

That night, I returned to my parents’ home. I was a sorry sight, having lost so much weight, and for the first time ever, my mother was regretful and willing to acknowledge the harm her decisions had caused me. But it was a very brief reckoning. What use was there in talking about the past? The damage had been done.

Divorce was a big taboo in the countryside back then. No matter how nightmarish your marital life was, divorcing your spouse was never an option, not if you weren’t ready to become a pariah.

That night, I lay in bed unable to sleep. I even had suicidal thoughts where I pictured myself running to the Dan River and jumping in. Once you’re cold dead, at least there’s no more suffering, no more thinking.

Story FM: This thought has haunted Han for many years.

After one of Wang’s many nights of gambling, she found a discarded notebook that had originally belonged to her son and wrote the following lines in it:

When all crops are ripening

I wear my cotton-padded jacket

I shiver still

What is better than frolicking in paradise? Nil.

Not even this world’s beauty that I hold dear.

Han’s first poem may not have been all that mature, but it was filled with her despair.

Han fought her suicidal fixations by thinking of her two children, particularly her daughter, who hadn’t even turned 10 yet. Nobody would care for this child like her own mother would, and Han longed to give her daughter a childhood moored in safety where she had a chance for a proper education. Han wanted to give her daughter the life she had never enjoyed.

Once again, she had no choice but to survive.

When her daughter was three years old, a fortune teller came to her doorstep. Seeing Han’s worn-out face, he revealed to her that he could see her suffering from three major losses in her life—her education, her career, and her marriage. Her grief was exceedingly heavy, the fortune-teller added, and she had shed enough tears to fill several small basins.

Han had thought this was an unescapable fate that she had to come to terms with.

Then she found poetry.

3

Poetry, Freedom, and 20,000 yuan

Get up, Shimei;

shake off your laziness.

I was yet to wake up

When I saw how cold

the four seasons were

March wind blew into my home

I showed my tenderness to the river and desert

Between my eyebrows is a litany of beautiful verses,

Waiting for the moon to rise.

—“Wake Yourself Up” by Han Shimei

Story FM: After that first, simple poem, Han began to wield her pen to vent her emotions on paper. If she didn’t know the Chinese characters for a word, she’d just write them in pinyin instead. At first, she used her son’s old notebooks. Later, she began using old receipts and pieces of kraft paper from old boxes. Anything is fit for writing as long as it has some blank space.

This newfound habit gave Han an outlet to reclaim her own identity, away from the burdens of motherhood and her failed marriage.

In April 2020, her son helped her register her own account on a short video platform. Soon enough, the algorithm had identified Han’s preferences and continuously presented her with poems from fellow netizens. Later, she also began to tentatively upload her own poems.

Others quickly learned of her talents.

Han: My main goal when I write poetry is to put my accumulated feelings of depression over the years onto paper. Whenever I’d find myself in a bad mood, I’d just look for some old notebook or a scrap of paper to write on. Soon enough, I found myself writing more and more.

In April 2020, my son encouraged me to download this platform where netizens upload short clips about whatever they want. When I saw people uploading all kinds of poems, I followed suit. At first, I would just comment under others’ clips. If I found my comments to be of high quality, I would write them down on a piece of paper, then type them in on my own account as a post and publish them online.

Other than the one trip I took to my hometown in Hubei when I was 18, I have never really traveled. So when I started writing, I couldn’t rely on memories of the sea, or the mountains, or anything much at all. I relied on what I’d seen in other people’s videos and my imagination. I would close my eyes and imagine myself standing by the seaside.

The sea is terrifyingly calm:

I throw a stone

But can’t even splash a single wave

On the horizon, the sun rises gently,

as soft as the moon flows

I gather wisps of morning glow

Boil a cup of piping hot tea

to offer to the sea

for some moisture on his dry mouth

—Excerpt from “The Sea” by Han Shimei

Han: Ultimately, I really want to inhabit whatever poem I am writing. It is a realm where all sorts of natural landscapes and, of course, love are readily available to me.

Many kind netizens have encouraged me and praised (what they call) my poetry, but I really find that label excessive for my simple rhymes. My vocabulary doesn’t have that many words to make people happy. I have very limited energy myself. It’s just that, as I enter my twilight years, writing my rhymes brings me some hope. It makes me feel that there is still some value and meaning to my life.

I’m no longer asleep

The waves of the sea embrace me

I struggled out of the haze

To greet the warm morning sun

Darkness there no more

Only ten thousand rays of light

I saw the dawn

I saw hope, for once not gone.

—“Awakening” by Han Shimei

Story FM: Since Han started posting her poems, Wang finally started noticing her. He downloaded the short video app as well, where he only followed his wife’s account and watched her share her poetry and interact with friends and fans. But he still failed to understand her, let alone her writing.

Media attention gradually grew, and one day Wang stood there while Han talked to a group of strangers in their family home about all sorts of stuff—writing poetry, freedom, love... It was all Greek to an increasingly uneasy Wang. All of a sudden, he felt accosted by the feeling of an impending crisis. He kept a close eye on Han and didn’t want her to continue writing poetry.

Han: I remember a certain morning when Wang and I were sitting on either side of the bed and I offered to read him some of the lines that I was just writing.

I live with a tree;

You don’t know how much it hurts me.

I live with a wall;

You don’t know how painful it is, not at all

I want to cry, but nary a tear.

I want to speak, but no words appear.

And really, my life was every bit like living with a tree or a wall. I had no sense of love.

Wang listened and said, “Don’t write about me!”

It wasn’t like he could understand a single word of what I was writing.

In September 2020, he began to unplug the internet cable and cut off the power supply at home. He was treating me like a prisoner, out of fear that I would manage to establish regular communication with the outside world and become famous.

He came twice or even three times a day to the canteen where I worked and called the security guard there several times to ask if I was still there. He was tracking my every move. Once, a couple of young female college students from Xinyang (another city in Henan) came to interview me at our family home. Wang scolded them and chased both of them out of the house. I felt so guilty and helpless.

I told him, “You are not going to stop me if I ever want to run away.”

Story FM: The more fans Han gained, the more Wang tightened his controlling grip on her. For a while, he would even turn off her mobile phone network while she slept.

Han couldn’t care less. She was able to write her poetry wherever she went; the village always had some safe corners away from Wang’s overbearing gaze. In those two years, she was also invited to read her poetry at several events for a fee. Han added these modest earnings to the money she’d saved from her factory wages: all in all, some 200,000 yuan. She had a plan for this money—buying her freedom from her oppressive, loveless marriage and a ticket to a new life filled with poetry and, perhaps, true love.

Han: In April 2021, Wang was causing so much trouble that both of my children agreed on the next step. “Mom, just divorce him.”

I filed for divorce, but he wasn’t appeased by my offer of 200,000 yuan. Three million yuan wouldn’t even cut it, he said. So I replied, “Well, I’m divorcing you all the same.”

I caused quite a commotion in our village, with people thinking that poetry had driven me crazy. Country folks are dictated by tradition. It is easier for them to get along and conform to a shared set of rules, and those rules dictate that divorce is immoral.

The way I saw it, though, a loveless marriage is like a set of invisible shackles. It’s no walk in the park, being born in this world. You have to try and achieve happiness.

Story FM: Ultimately, Han did not get much support, not even from her daughter. Han had confided in her that she still hoped for true love in the future, perhaps marrying again to a proper husband. Her daughter believed that she was being naive and unrealistic, and that she would end up disappointed again.

Han was on her own. She shared her story with Zhuang, a divorce lawyer that she found on Weibo who subsequently offered legal services pro bono. Thanks to Zhuang, Han learned that when a plaintiff files for divorce without agreement from the other party, there must be a court proceeding to dissolve the marriage. Thus, Zhuang helped her file for divorce successfully on May 9th, 2021.

For a while, Han was filled with excitement and hope.

But then came a text message from her daughter. She was not going to interfere with her decision to divorce, but she hoped that Han could wait until she had sat her university entrance exams.

Faced with her daughter’s petition, Han woke up again from her dream of freedom. No matter how much she longed to be her own true self, she was a mother first—and ultimately a victim, too. She felt obligated to withdraw the lawsuit, and her commitment to her children’s wellbeing put out the orange light that had just begun to flicker in her heart after such a long time.

One by one I took my ribs out

For my children to climb onto heaven, no doubt.

I will protect you in the rain,

And in the waves lift you away from pain.

In winter I will be your heater for you to warm by,

In summer I will be your cooling mat.

If need be, know

I will give my life to you both, right now.

—“A Mother’s Confession” by Han Shimei

Han: It’s hard for children from a single-parent household to find a spouse, at least in the countryside. This weighed in my mind when I made my decision. Most of my life is behind me, anyway, and my hair is all gray now. I felt that I had to get over my grievances.

Now that I have withdrawn the lawsuit, there are all sorts of things that I find myself unable to just dump onto paper. I can only cry them out of my system, or else consider them my own bitter wine to drink.

I live with this knot in my heart, but apart from that everything is fine. And I do still have my rhymes. I am physically chained to my household, but in the end, my soul is free. I am free to imagine love in all of its beauty and a bright, alternate life spent in freedom.

My days and nights fade together.

Have you seen it?

I stand at the end of my tether,

Dancing on the tip of this knife.

My blood flows and dyes red

the road that our hometown spreads.

I stand at a crossroads and wave your way, just like that.

If the breeze passes by my side,

I regard it as your gentle greeting for the day.

Have you seen it?

I still dance for you on the tip of this knife

—“Dancing on the Tip of a Knife” by Han Shimei