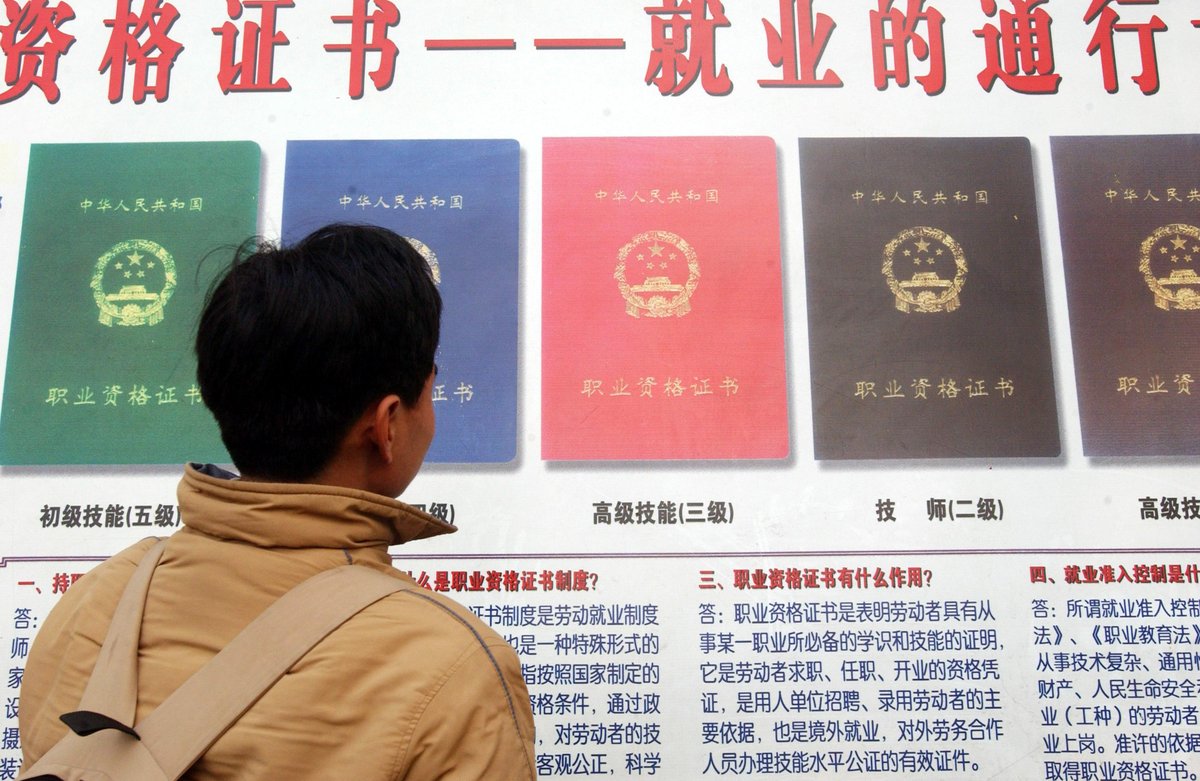

Young workers are turning to qualifications, exams, and certificates to stay ahead in a competitive job market and to feel productive in their spare time

With his new 30,000-yuan certificates in hand, 22-year-old Song Weiqing was ready to conquer the job market—or so he thought. But after spending three months training at Saipu Fitness Academy to gain fitness instructor and nutritionist certificates, Song found employers were unimpressed by his hard-earned credentials.

Despite Saipu’s website brimming with promises of glittering job prospects post-certification, “HR departments don’t even look at my certification paper,” Song tells TWOC. They were much more interested in his willingness to work overtime than his academic achievements.

Song’s disillusionment is not an isolated incident but a symptom of a trend for certificates sweeping the nation. Young workers are increasingly spending their spare time preparing for exams in the hope of standing out in a crowded workforce or as a way of fostering self-improvement. But with many courses unrecognized by employers or unregulated by the government, the likes of Song are often left disappointed despite investing significant money and effort in certificates.

According to China’s Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, more than 11 million people nationwide obtained professional certificates in 2022, an increase of more than 80 percent year-on-year. In Jiangsu province, for example, the number of applicants for the Social Worker Certification Examination increased by almost 70 percent this year. The craze has spread into hobbies too, with certificates covering everything from arts to sports, dance, and more.

Peng Ting spends most of her spare time studying for qualifications. Having taken dozens of exams, the 29-year-old from Shenzhen, Guangdong province, now has over 20 certificates, including a Certified Public Accountant (CPA) qualification, a Lawyer’s License, and the TOEFL English language proficiency certificate.

For Peng and other young workers, a degree from a top university is no longer enough to land a high-flying job in big cities. “Education is a must, but certificates are the icing on the cake,” says Peng. After obtaining her CPA qualification, she secured a job in the investment field.

However, preparing for exams can be challenging. “The CPA, for example, usually takes three to five years to finish all six subjects. It’s hard for people working full time to prepare,” says Peng, who was working as a lawyer and only has spare time during weekends.

Certificates also come at a cost. Expenses for exam registration, training courses, and transportation and hotel bookings for exams all add up. To prepare for her TOEFL exam, Peng spent nearly 10,000 yuan on online English training courses.

The huge demand for certification has given rise to a prosperous training market. According to media outlet Financial News Network, China’s certification training industry reached 38.6 billion yuan in 2021 and is expected to double by 2026.

Lu Na, who asked to use a pseudonym for this article, runs online training courses for nutritionists. “The worse the economy gets, the more people are eager to obtain certifications,” 42-year-old Lu, who used to work in finance, tells TWOC. In 2021, authorities reinstated the Public Nutritionist Qualifying Examination (PNQE), which had been discontinued in 2016. The PNQE can lead to higher salaries in careers like babysitting or nutritional consulting for athletes, according to Lu. “It only takes two months for my students to prepare and then they can take the exam,” Lu explains.

However, the boom in certificate providers has also brought an influx of scammers. For example, state media outlet CCTV reported in December 2019 that a company calling itself the American Certification Institute illegally sold registered counselor certifications for 850 yuan each. To stop fake certificates from circulating, the government has set up a nationwide network for checking state-issued certifications. But certificates issued by non-government organizations remain largely unregulated with the quality of courses and industry acceptance of certificates varying widely.

Still, authorities are encouraging the certification craze. In Shenzhen, for example, the local government gives 700 to 3,000 yuan to citizens who obtain certain qualifications. On the Instagram-like social media platform Xiaohongshu, there are over 100,000 posts related to these “certificate subsidies.”

Some cities also count certificates for residents applying for household registration (hukou)—a designation that can allow residents a range of perks from the right to purchase property and cars in the city, to easier access to healthcare and education services. In Shanghai, for example, obtaining a state-issued engineer’s certificate or teacher’s certificate helps with obtaining a household registration. This has spawned an industry that specializes in training people for certificates to help settle in cities like Beijing or Shanghai.

“Compared to other ways to obtain household registration like a diploma from a top university, or getting a high-ranking job with a salary significantly higher than the average income, obtaining certifications is relatively simple,” Li Jun, the head of a household registration consulting agency in Shanghai, tells TWOC. “Our clients are mostly ordinary working people with just a high school diploma or an associate degree in college. So [certificates] are a more practical choice for them.”

The obsession with certification has entered non-professional realms too. Ma Miaoran, a 28-year-old internet company worker from Hubei province, spent 400 yuan on a badminton exam and certificate. “I took the exam for fun and got the certificate to prove myself. That’s enough for me,” Ma says. She is a “level nine” badminton player according to her certificate—she plans to take the exam again to try and reach a higher level.

Peng is also considering more certificates unrelated to her work. “I consider it a way to invest in myself...If work is not that busy, I would use my spare time for self-improvement, rather than wasting it,” she says. After working hard to get her Lawyer License and accounting qualification, she has obtained Japanese language certificates and a computer programming qualification. Next up: a surfing certificate.