From Kaifeng to Jerusalem—a Chinese Jew tells her story of leaving for the Middle East and reflecting on her dual identity

This story was originally published in podcast form by Story FM.

Jin Jin is a young woman born and raised in Kaifeng, a prefecture-level city in east-central Henan province, China. Growing up, she always heard about her Jewish heritage from her father.

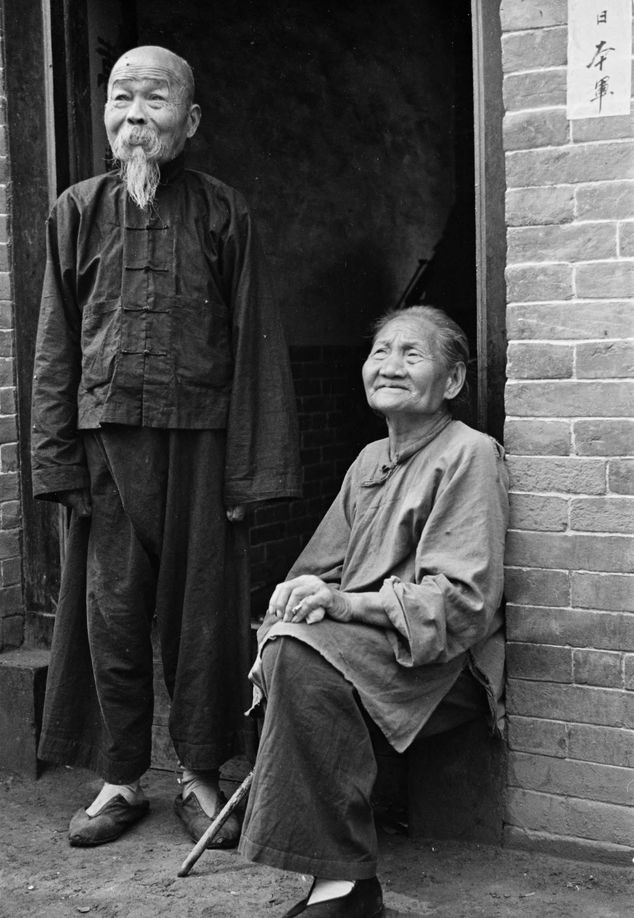

The origins of Jews in China can be traced back to the Northern Song dynasty (960 – 1127), at a time when an exiled Jewish congregation entered China through the Silk Road before winding up at China’s capital—Kaifeng. In stark contrast to many other countries at the time, the Song emperor exemplified China’s tolerant stance by granting them the right to stay and even their religious freedom.

Having been spared from discrimination, the Jews settled down rather happily, learning local customs, marrying Han people, and even sitting the imperial examinations. Gradual assimilation was inevitable, and by the Qing dynasty their presence in the region was referred to as “seven surnames, eight families (七姓八家).” Two of these Jewish clans retained the surnames of Zhang (张) and Zhang (章), which sounded the same but with different Chinese characters, while the rest went by Zhao, Ai, Li, Shi, Jin, and Gao.

With the passing of the last Rabbi in China at the end of the Qing dynasty, Kaifeng Jews gradually saw their culture, including the native Hebrew language, fade away. This has indeed been the case for Jin Jin, who belongs to a generation virtually indistinguishable from her Han peers. There were only two peculiarities to her household: the family’s abstinence from eating pork and their home as a historical site for Jewish tour groups from all over the world to learn more about Kaifeng Jews and their history. Jin Jin always helped her father manage these visits, and affectionate travelers often wanted to take their picture together with her as this little mascot of sorts.

Here is Jin Jin’s story:

1

Communicating via email

Jin Jin: My Chinese name is Jin Jin, and I am a Chinese Jew.

Back in junior high school, I had every foreigner I met leave an email address because I wanted to get a copy of all these group pictures. Because we did not own a computer back then, I spent a good number of years going to an internet cafe on weekends to stay in touch with these tourists, following my dad’s orders. This form of communication went on for years.

I did not identify as Jewish at that point, nor did I have any impressions about Jews. They’re just another ethnic group. I just considered myself Chinese.

Story FM: On May 14, 1948, David Ben-Gurion, the head of the Jewish Agency, the operative branch of the World Zionist Organization, proclaimed the establishment of the State of Israel. The Law of Return, passed on July 5, 1950, granted every Jew in the world the right to settle in Israel, meaning any person either born to a Jewish mother or having otherwise converted to Judaism as their sole religion can return to the motherland and be granted Israeli citizenship.

Influenced by the previous generation, Jin Jin’s father was eager to return to Israel.

JJ: My father is not well-educated. I don’t think he even went to middle school, but he has a sincere heart. He is very determined about his beliefs. My grandfather told him on his deathbed: “We are Jews. We must go back [to Israel] if we ever have the chance.”

I am not so sure that my grandfather was really thinking about immigrating. I think it was more likely that he merely meant visiting Israel, the birthland of our ancestors. In any case, Dad came up with his own interpretation of his late father’s words, and he’s never given up on that idea.

Upon the death of his father, Jin Jin’s dad took it upon himself to visit the surviving Kaifeng Jewish families. Every holiday presented him with a chance to listen to stories about their shared community.

JJ: My father believes that my grandfather’s last words echoed the unfulfilled wish of a generation.

I recall this one time when we had visitors from abroad, and my father took me to the home of a member of the Shi clan. Mr. Shi was already having mobility and communication issues due to his advanced age, so Dad helped him communicate with his foreign visitors. I couldn’t even understand some of the things they were saying but it’s apparent that Mr. Shi was passionate about recounting his own story and had a deep sense of pride in his Jewish identity. Our visit left a deep impression on me, and with Mr. Shi passing away just a year later as many other elders did in close succession, I realized that it was a privilege to sit down and listen to their memories and recollections.

2

Jewish visitors from overseas

Story FM: With their elder generation dwindling steadily, the burden of an eventual return to their homeland fell on the shoulders of the next generation, represented by those like Jin Jin’s father. He was adamant about carrying the torch, at least as much as his age and limited schooling allowed him to. He placed his hopes for a full return to Israel on his eldest daughter.

Coincidentally, in 2002, a Jewish American named Timothy Lerner traveled across the ocean and came to Kaifeng.

JJ: At that time, a family friend from Beijing brought a group of foreigners to Kaifeng, and they invited members from all the local Jewish families to a large dinner party. This friend warned us that one particular guest from the group might arrive a little late because his flight had been delayed.

We’d almost finished our supper when a blonde man finally came in. He was clad in a green down vest, carried a rather large bag, and seemed to focus solely on his meal. I figured he was starving after his lengthy trip.

As it turned out, this wasn’t the last time he’d come to our house. During his second visit, I heard from my dad that our guest intended to stay in Kaifeng as a teacher and he wanted to learn more about our lives. His name was Tim.

3

A Jewish man named Tim

When I was young, I had a hard time keeping track of everyone who came to our home with their own stories and intentions. Some vowed to offer financial help, while others said they would assist us in returning to Israel. Some even said they would open businesses in Kaifeng. But we rarely heard back from any. We soon learned to treat these as one-off encounters.

Tim, however, is one of the very few who really did stay by our side to help. I got to be relatively close to him.

Initially, Tim wanted to teach English to the Kaifeng Jews, but it’s hard to earn the trust of a reclusive small-town community like ours. My dad, ever-hospitable, was the one who eventually introduced Tim to various local families. Still, only I showed up to his English lessons.

Tim was teaching at Kaifeng University in the western suburbs of the city, a good 40-minute bus ride from my home in the eastern part of town. To make things extra tricky, I only had half a day off back in middle school. Fortunately, Dad happened to be working fairly close to Tim’s place. So my father would meet with me after clocking out and we would head home together with Tim’s dirty laundry. My mom would clean them and have me bring the load back to him the next week.

Eventually, I became familiar enough with Tim that he would come to our house and spend most of his day here. By the time he was out the door, it was about bedtime.

Story FM: After Tim settled in Kaifeng, he co-founded a small school with Jinjin’s father to teach Hebrew and English to local Jews. Tim provided the funds, while Jin Jin’s father offered his own family home as a temporary venue after they tried a litany of vacated factories and shops.

Jin Jin’s father knocked on local Jews’ doors to persuade them to enroll their children. He was the one who chose the school’s name: Yiceleye, a word that existed as far back as the Song dynasty and is a transliteration for “Israel.”

JJ: During his time at Kaifeng University, Tim taught us Hebrew and some simple knowledge of Jewish lore and customs.

The small school was divided into several classes. Back when I attended, there were some five or six young students my age who picked up the language relatively quickly, and then some seven or eight people my father’s age. At the time, the focus was largely on language learning.

4

Shavei Israel

Story FM: At the Yiceleye School, Jin Jin learned the basics of Jewish culture and celebrated traditional festivals with her community. Some of those required some adapting to as they live in China. Such was the case of Shabbat, the seventh day of the Jewish week, typically a day of rest and abstention from work. Kaifeng Jews contented themselves with a simple weekend get-together.

Later, Tim contacted Shavei Israel, an Israel-based organization advocating for people of Jewish descent to return to Israel. The organization had helped Jewish descendants scattered in India to settle in Israel, covering the cost of their entire operation.

At the end of Jin Jin and her peers’ studies in Tim’s school, two Rabbis and a representative of Shavei Israel visited China to inspect the living and learning conditions of Kaifeng Jews.

Three months after they left, Jin Jin’s family received a notice that their eldest daughter could now move to Israel to effectively start the process for her “Aliyah,” the immigration of Jews from the diaspora to Israel.

JJ: I remember waking up, washing my face, and looking in the mirror on that fateful day. Tim was at my house, where he informed my parents that I was now officially part of a small group departing in just two weeks. Our flights to Israel would depart on January 18. With my plane ticket already bought, this was final.

I always knew we were going to leave at some point, but I wasn’t sure when that would happen. When my mother told me the exact date, I burst into tears at my own reflection in the mirror. “Why are you crying? Didn’t you always say you wanted to leave me?” she asked.

I was certainly going through a particularly rebellious stage, riddled with jealousy of my newborn sister. In my eyes, she had stolen my parents’ love and attention that was formerly focused exclusively on me. I felt excluded from the family and once told them that I would run away. It was a rough spurt, but the news of my actual imminent departure made me cry with sorrow.

As for my father, I didn’t see much of him for the next little while. He remained silent and kept himself busy, whether buying stuff for my luggage or inviting guests to dinner. I finally caught sight of him again as some acquaintances carried him back home, along with his wallet that he would have otherwise neglected. There was no point in trying to talk to him—he was very visibly drunk and unresponsive. I had never seen my father like that.

Many years later, when I asked Dad about this incident, he said he was just so happy that I was finally going to set foot in Israel.

I had never left home before that. I went to university in Zhengzhou, a city only one hour’s drive away from home, and my Dad still thought that was too far. When others aptly pointed out that this mindset seemed incongruent with shipping his daughter to Israel, he replied that this was an entirely different matter.

5

My first time in Israel

Story FM: After the Lunar New Year holidays in 2006, Jin Jin boarded a plane to Jerusalem with three other girls from Kaifeng. The small group was taken on a visit to the Western Wall (also known as the “Wailing Wall,” the Katel in Hebrew, and the Al-Buraq Wall in Arabic) in the Old City of Jerusalem. Following the tradition, Jin Jin wrote her father’s wish on a note that she left in a crevice of the wall: “May Kaifeng Jews have a smooth return to the Land of Israel.”

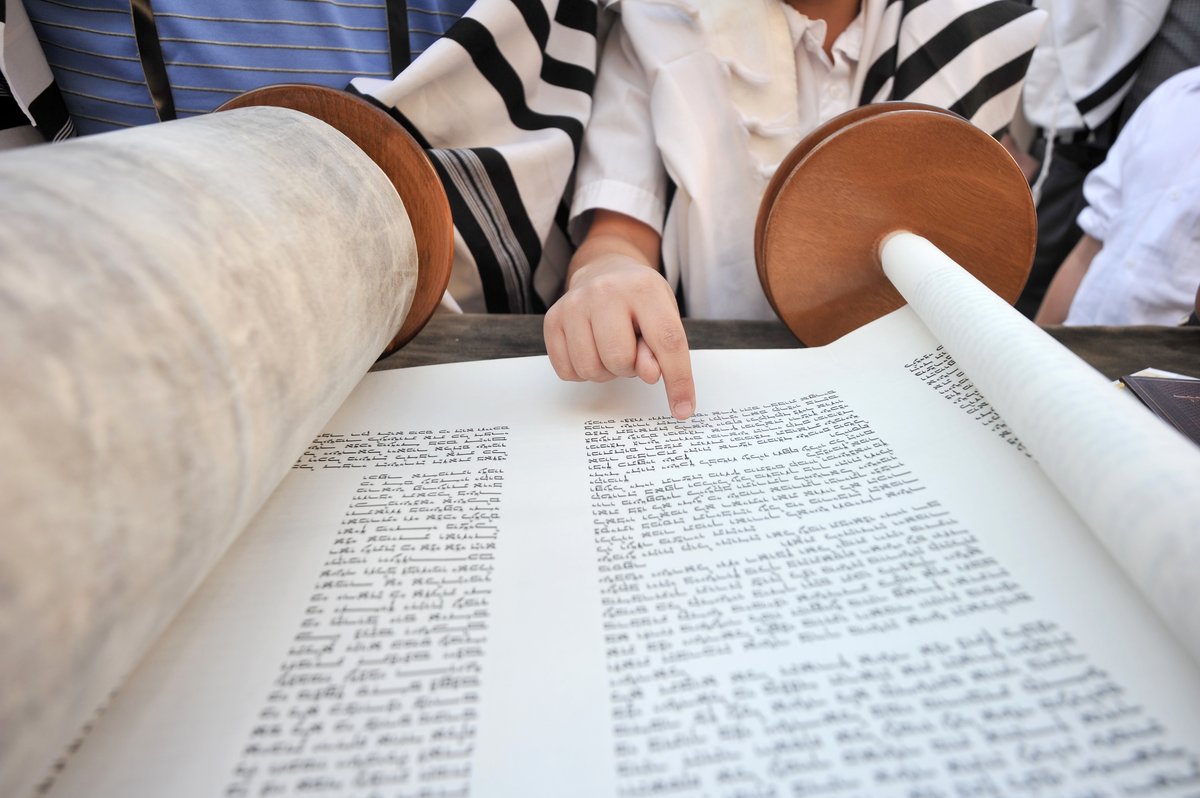

However, their eventual immigration wasn’t easy. To be considered Jewish (for the purposes of immigration to Israel), you must be born to a Jewish mother. Having settled in China for over 1,000 years, Kaifeng Jews follow instead the Chinese patrilineal tradition. Therefore, and in accordance with Israel’s Law of Return, they must study Jewish law and pass a series of religious examinations to eventually convert to Judaism before gaining official recognition by the Israeli government.

After praying at the Wailing Wall, the girls were led by their Shavei Israel hosts to a religious school in the suburbs of Jerusalem.

JJ: When I got off the bus and saw our school, I turned to the girls and said, “I want to go home.”

We were lodged in what they called caravans, wooden portable building units typically used in early Jewish settlements because they were easy to build and move around. They made for extra harsh winters and sweltering summers. With grass growing through the planks in our rooms, we quickly became acquainted with some unexpected visitors: bugs, spiders, and slugs.

We arrived there on a Thursday, with our counselor instructing us to “look and shop around” in a small supermarket in the village. We decided against buying a full cart, thinking that the supermarket would open daily and that we should decide what we truly needed first. That was our first practical lesson on Shabbat, which happened to be the following day.

When we woke up in the afternoon after a long sleep, everything was close. The supermarket, the school, everything. We were supposed to be placed under the care of a foster family, but our counselor had yet to make the arrangement, probably assuming it was best to give us some time to adapt to our new environment.

And adapt we did. For the next two days, we appeased our bellies with the all snacks we’d brought from China. In hindsight, that was pretty funny.

We were part of a cohort of 16 students. After a long day of work, the other students would play some music, have a small drink, smoke a cigarette, and even dance a little. Their behavior fascinated me. I had imagined them to be pious, reverent, and wearing black daily. None of these assumptions proved to be true with our fellow foreign classmates.

We all got along very well and blending in was easy thanks to everyone’s constant kindness. We occasionally invited our classmates to have Chinese food with us and, during the Lunar New Year holidays, we made traditional Chinese paper cuttings to decorate the windows together. However, we were still there with the ultimate goal of passing the exam that would prove our Jewish identity.

Since birth, my parents had told me that I was a Jew. Here, though, I was suddenly presented with this need to pass a test and convert to Judaism before a group of people could decide that I was, indeed, a Jew with all due qualifications.

There really was a lot to learn. We had daily classes that went into Jewish law, art, Hebrew, reading and study of Tanakh, the Hebrew Bible. Scripture reading was not my forte. Any prayer that my classmates could read and complete in fifteen minutes, I needed an hour for.

Jewish law addresses all sorts of questions concerning prayer and religious practice in daily life. How should you pray before eating apples or potatoes? What are the specifics of making tea on Sabbath? That kind of stuff.

Prayers were like our daily homework. Jews bless the water they are about to drink, so we taped the prayers to our drinking glasses to try and accelerate the learning process. Custom dictates you also join anyone around you who is praying to close their recitation with an “amen.” This meant that whenever I prayed, eyes on my glass, my classmates would halt whatever they were doing to close the prayer together. Any progress in our memorization was met by general praise and encouragement from teachers and other students, reinforcing our learning.

6

Purim

I will confess that at first, I thought that this rigid set of guidelines confined those around me to a rather unremarkable life. That was until I attended my first Purim, (meaning literally “lots” in Hebrew) and witnessed everyone’s creativity in this crazy masquerade party.

Story FM: Purim commemorates the saving of the Jewish people from annihilation at the hands of Haman, an official of the Achaemenid Empire (probably in the 5th century BCE), as recounted in the Book of Esther.

Haman despised the Jewish people so much that he proposed their extermination to King Ahasuerus. His plans were heard by the young orphan Esther, newly crowned as queen and secretly a Jew herself. With the help of her guardian Mordecai, Esther eventually thwarts Haman’s plot, persuading King Ahasuerus to hang the evil vizier on the very gallows he had prepared for Mordecai. During “Purim” Jews are supposedly obligated to drink until they do not know the difference between “cursed be Haman” and “blessed be Mordechai.”

JJ: Just about everything was permitted for Purim. One of our religion teachers, usually a fairly strict man, got drunk to fulfill his holiday obligations. Everyone caked themselves in makeup and donned their festive clothes and costumes, with no restrictions. Boys wore female clothing, with some even pretending to be pregnant. One of our fellow senior students wrapped herself in her own sheets and quilt.

Purim was our first holiday celebration in Israel and the one event that suddenly changed our perception of observant Jews.

7

A change of identity

Story FM: Jin Jin enjoyed a mostly simple, joyous stay in her school, following her instructors to the synagogue to pray and learning to read the Hebrew Bible. However, the fact remained that this was her first time living abroad alone. Homesickness struck her often and made her sometimes consider returning to China after completing her studies.

However, Jin Jin only began to really reflect on the dual nature of her identity when the ramifications of the ongoing conflict in the region manifested in her life.

JJ: My foster father was a kind-hearted musician who often wrote prayer poems and spent his free time protecting the environment by picking up garbage in the village. When he wasn’t writing music, he would frequent the small grove in our village to pray.

On a particularly foggy day when you could hardly see anything past your immediate surroundings, I went to town for my lessons and returned to our school at around 8 p.m. Our counselor was waiting there for us. “Jin Jin, your foster father has passed away.”

I was so shocked. “How could he die?” I asked the counselor. “He was doing well this morning.”

The counselor told us that he died in a car accident due to fog. I didn’t buy the story because I saw a police car on my way back to the school. But I didn’t have a clue of what had happened. This went on until the next morning at about 6 o’clock when all students were called for an assembly where the counselor finally revealed the truth. My foster father had been praying in the woods when he was stabbed to death. His attackers were later identified as two Arab youths, both of them minors.

Until that moment, the intensity of the conflict between Jews and Arabs had escaped me.

Our village was a very special place. Unlike other regions in Israel, there were no fences separating our settlement from the Arab village just 40 minutes away—just over a hill.

I felt the inhabitants of our village were brave. Most of them were American immigrants whose religious beliefs had motivated them to leave behind their cushy lives in the US to settle in a land that would have otherwise been assigned entirely to Arab residents. Their houses stood in the darkness of the settlement, without any lights or proper roads in the immediate vicinity.

As for myself, I had yet to truly process the shock of my foster father’s murder. Only at his funeral did I muster the spirit to tell my mother the tragic news over the phone. I told her he died in a car accident because I had wanted to spare them from excessive worry. But I still burst into tears as I narrated the make-believe story of his death. I was so very sad that this outstanding man was now gone.

This tragedy affected me deeply. In fact, I found myself in a contemplative mood. Why were my fellow foreign Jews here in Israel? For most of them, surely it was not due to hardship in their home countries that they had no other choice. So where did their religious devotion stem from

Far from sparking answers, my questions only led me to an even deeper process of soul-searching. What was my own purpose in coming here? Did I really just plan to go back to China once I got my brand new Jewish identity, sanctioned by the State of Israel?

For the first time ever, I started to reflect on the meaning that I conceded to my own identity within Judaism. I had strived to become a good Jew. I wanted to gain all my credentials as a Jew. Even if at first I had balked and considered the option of giving up and going home, this was no longer an option for me. No matter how strenuous my studies were in this remote land, I would persist and rise over the challenges.

8

“God is able”

Story FM: A year later, Jin Jin sat her religious examinations and final interview with three Rabbis. This was the last step for her to become an officially recognized Jew in Israel.

JJ: My examiners asked me whether I was planning on taking a Jewish name. I said yes.

Most Jewish names come from the Tanakh, which I consulted in choosing my name. My Chinese name starts with a J, but there is no such letter in Hebrew. The closest sound was that of the letter “-י” (read “yod” in Hebrew). Eventually, I settled for Yecholiya. I liked the sound of it, even if I did not know its meaning at the time.

Having finally chosen a name, I went happily back to my tutor. “Do you know what your Hebrew name means?” He said, “It means God is able.” I was thrilled. I couldn’t possibly have chosen a better name for myself.

The Rabbi, too, asked me about my new name after the exam—he was confused about where I had got it from. I said I had picked it from the Torah, the central and most sacred part of the Jewish Bible. It was right there when they searched the Scriptures. My chosen Hebrew name really did exist.

Later, this became a running joke in the community. A Chinese Jew had traveled all the way to the Land of Israel, where she’d cracked open the Torah to show a Rabbi the location of her chosen name in the Holy Scriptures.

9

Entering the kibbutz

Though we were now certified Jews, we still had to apply for Israeli citizenship. The process took half a year, so in the meantime, we moved to the nearest kibbutz.

Story FM: Kibbutz are intentional communities operating as collective farms in Israel, usually in rural areas. Nowadays they have expanded to house industrial and high-tech sectors, among other businesses. There is no private property in a kibbutz, nor concepts such as wages. Food, clothing, housing, transportation, and medical care are all free of charge. Therefore, kibbutz were the most affordable option for new immigrants like Jin Jin while they waited for their citizenship to be processed.

JJ: I made up my mind to stay in Israel after spending time in the kibbutz. I believe that my relationship with God and the Land of Israel is a gradual process that His hand directs. Thus, I regarded my stay in the kibbutz as another chapter towards my settling in this country. There was a difference with my previous life in the religious school, though. There, I had been mostly concerned with gaining knowledge of religious thoughts and Jewish concepts. At the kibbutz, I mostly worked the land.

Our farm was relatively large, with 700 inhabitants. I had started out with these grand plans to raise cattle, but the stench from the cowshed right next to our dormitory quickly made me give up the idea. In any case, we could try out all sorts of roles if approved by our counselor. I ended up choosing the vineyard out of my love for grapes, particularly Israeli ones—they’re wonderfully sweet

Every morning we went to work at around 5 a.m., when it was still dark, and ate in the cafeteria at noon. Once we clocked out at around 1 p.m., we were free to do as we pleased.

Honestly, I didn’t feel farm work was all that hard, though it did get a bit too hot in the summer. One day I was busy digging potatoes under the scorching sun. By the time the counselor asked me to leave at noon and I made it back to the dorm, I realized that it was 53 degrees centigrade outside and I was about to turn into a baked potato myself.

After working for half a day, we would go back to take a shower and throw our dirty clothes into the collective laundry room, which you didn’t need to attend to. You could just do your homework in the afternoon.

Israeli soil is not very fertile. It’s not unusual at all to find places where nothing grows. However, we still managed to grow the sweetest, largest, most delicious fruits.

I felt that I was forging my own relationship with the land through agricultural work. It was a land I could now finally begin to love.

10

Settling in Jerusalem

Story FM: Jin Jin stayed at the kibbutz for half a year before finally gaining Israeli citizenship, granting her the right to live and work legally in Israel, and even settle there permanently if she wanted.

JJ: All four of us girls returned to Jerusalem, at least for a brief while. One of them had met an American guy in the kibbutz and they eventually tied the knot and left for the US. That left three of us in Jerusalem.

One of the younger girls took preparatory courses at college with me. Throughout my time in college, I worked in a café next to our dormitory—this made me feel like I was already integrating into Israeli society. We were allotted some governmental subsidies for new immigrants, too, so our basic needs and living expenses were covered for the most part.

When I was at college, international Chinese students would hold gatherings once every week or two, getting together to cook and chat. I went to one of those meet-ups, but they did not invite us for a second. They argued that since we had obtained our Israeli citizenship, we did not really qualify as international students. It was kind of a big blow to me back then. Weren’t we all Chinese? It was just an excuse to have a meal and enjoy some time together, but they were actively excluding me from their circle. So I didn’t make a lot of friends during my college years.

Luckily, things changed when I moved on to a school for tour guides. Here, I was surrounded by quite a few students hailing from a shared Chinese cultural background. Some of us were from the Chinese mainland, while others came from Hong Kong or Taiwan. Some had married an Israeli, or otherwise studied here. Most of them were not Jewish.

The Israeli identity (or the lack thereof) aside, it was the first time I got to see so many Chinese people together here in Israel. Out of a class of 38 people, I think over 20 of us were Chinese. I had been looking forward to going to class because, at the end of the day, I wasn’t in the classroom to study so much as I was hoping to chat with everyone, eat with them, and just have fun.

Eventually, I made a lot of good friends and we all had a really joyful time. In fact, we’re still in touch.

Story FM: At the tour guide training school, Jin Jin met her current husband, a Shanghai man. They now reside in Jerusalem with their one-year-old son.

Every Lunar New Year, Jin Jin returns to Kaifeng to spend some time with her family. Back in her birth land, the familiarity of her childhood days is still present. Jin Jin now feels that she is both Israeli and Chinese and that this duality will accompany her throughout the rest of her life.

Podcast episode produced by Ma Da (马达)

___

This story is published as part of TWOC’s collaboration with Story FM, a renowned storytelling podcast in China. It has been translated from Chinese by TWOC and edited for clarity. The original can be listened to on Story FM’s channel on Himalaya and Apple Podcasts (in Chinese only).