From celebrations of workers at the 1959 National Games to vast displays of technological prowess during this year’s Asian Games, China’s opening ceremonies have evolved dramatically over time

As the opening ceremony of China’s 1959 National Games reached its conclusion, children suddenly broke from their performance formations and dashed pell-mell across the stadium in Beijing. They raced up to the spectators and flung bouquets of flowers into the cheering crowd of workers—it was a celebration of labor, of youth, and of the revolution that had birthed “New China” a decade earlier.

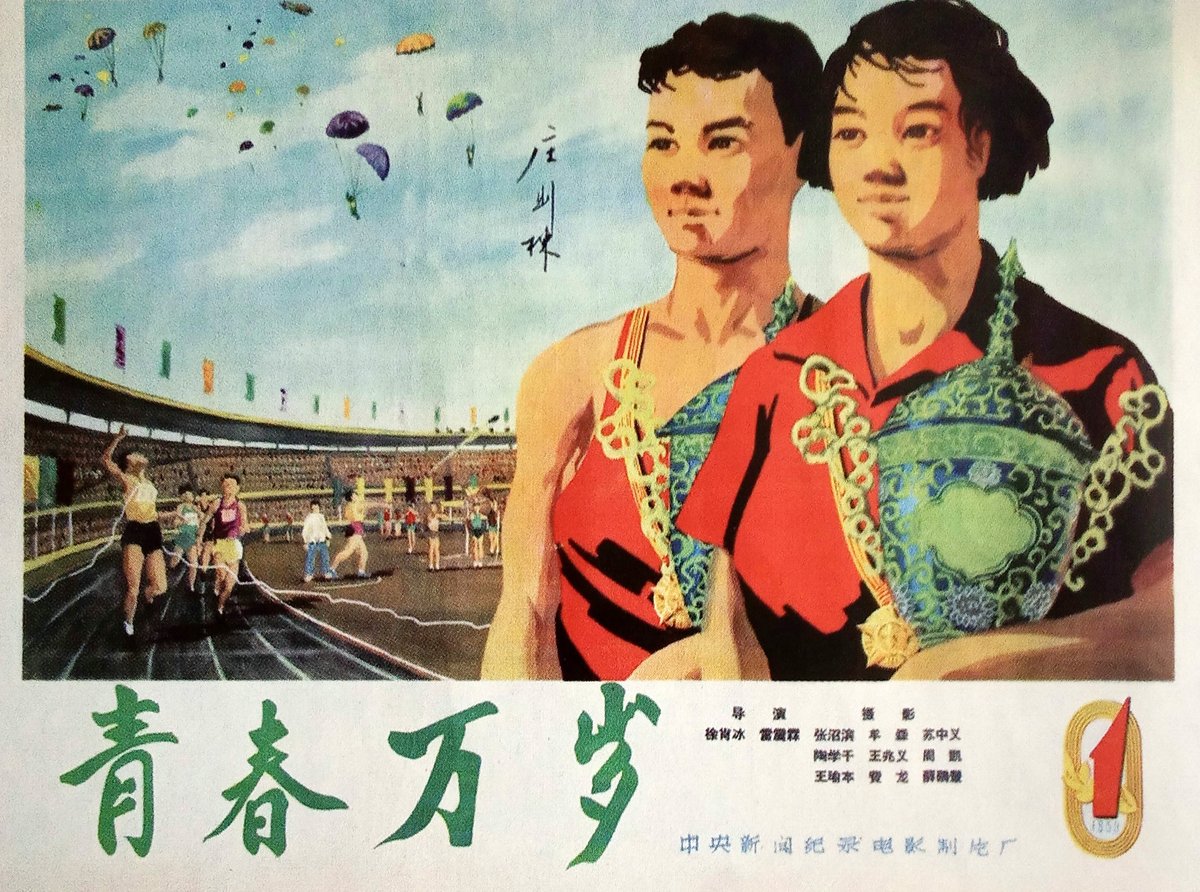

The scene, captured in Long Live Youth (《青春万岁》), a documentary about the Games released later the same year, is unexpected, chaotic, and thoroughly joyful. Over six decades later, on September 23 this year, China opened another mass sports event. The 19th Asian Games began in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, in a blaze of advanced technology, jaw-dropping choreography, and precise timing. Unlike in 1959, there was no chaos in the Hangzhou ceremony: it was a show of control, with digital systems and human performers in perfect synchronization.

While 1959 was a celebration of political fervor and the birth of a new nation, Hangzhou’s spectacle was a showcase of China’s technological progress and cultural roots—themes that have been prominent in similar performances since the 2008 Beijing Olympics, when director Zhang Yimou ushered in a new era for opening sports events in China. From 1959 to today, opening ceremonies in China have evolved substantially, and choreographers and directors now live firmly in the shadow of 2008.

In Hangzhou, a digital economy hub where technology giants like Alibaba and Hikvision are headquartered, director Sha Xiaolan organized a show of CGI, virtual fireworks, and drones in the 80,000-seat Olympic Sports Center Stadium. In an echo of 1959, the ceremony culminated with a child racing across the stadium—but this time it was an adolescent wrapped in a motion-capture suit, which allowed him to transform into a CGI colossus, capable of crossing the Qiantang River in a single stride, appearing before the crowd as a giant hologram.

The march of the digital giant was followed by digital fireworks exploding over the Hangzhou skyline, closing out a lengthy presentation of dance and music performances that drew heavily on traditional culture.

State media Xinhua News called the ceremony “a celebration of unity in diversity,” and highlighted the Games’s “green and sustainable” credentials. While the digital fireworks provoked some consternation among locals expecting conventional pyrotechnics, the zero-emissions substitutes were lauded in green circles.

Mainly, the show communicated a message about China’s enduring place in a pan-Asian community and the country’s technological prowess. The show echoed the sleek perfection of 2008—In fact, Sha worked alongside Zhang for Hangzhou’s effort.

It is no surprise that the Beijing Games have remained a benchmark for opening ceremonies. The Olympics in 2008 provoked genuine, lasting patriotic pride and served as a signal to the world that China had returned as a cultural and economic superpower. “The Olympics will redefine the way people see us,” a Beijing resident quoted in the New York Times announced that year. In 2011, researchers from the Shanghai International Business and Economics University, DePaul University, and the Rochester Institute of Technology used the more cynical language of marketing: it was a successful “strategic branding event” for the nation, albeit at the cost of 100 million US dollars for the opening ceremony alone.

No gaffes could be tolerated. There would be no breaking from formation. Emblematic of the drive to erase any flaws was the controversial replacement of seven-year-old singing prodigy Yang Peiyi with the supposedly more adorable but less euphonious Lin Miaoke for a performance of “Ode to the Motherland.”

Zhang’s ceremony set a model for the cybernetic mixing of human performance and technological tools. Zhang drew this element from the CGI-heavy martial arts epics, like Hero (2002) and Curse of the Golden Flower (2006), that he produced in the runup to 2008, and cranked it up for the mass spectacle, filling the stadium with beings that were not easily identifiable as either human or technological. Hundreds of dancers interacted seamlessly with flowers projected onto a massive screen under their feet, while it was difficult to separate flesh from digital creations when dancers performed inside printing blocks illustrated with computer graphics. This summoning of “digital multitudes,” as Jason McGrath, a Sinologist at the University of Minnesota termed them, became a mainstay of future ceremonies.

Chen Weiya, who had assisted Zhang in 2008, helmed a broadly similar spectacle for the 2010 Asian Games in Guangzhou, Guangdong province: Tightly choreographed displays of human-machine interaction, massive light shows, and mixtures of tradition and technology presented on a massive stage by the Pearl River (the first time an Asian Games opening ceremony had been held outside the main athletics stadium). The spectacle highlighted the skyline of the modern metropolis, including the 604-meter Canton Tower built in the run-up to the games.

When Zhang himself returned for the 2022 Winter Olympics opening ceremony, he did not veer very far from the template he laid down fourteen years earlier. The ceremony in 2022 took place in the same Beijing National Stadium (also known as the Bird’s Nest Stadium) as in 2008, and featured ice hockey players hitting an LED puck, a giant screen beneath performers’ feet that lit up with glowing snowflakes as they danced across the stage, and a Chinese flag passed around representatives from each of China’s 56 officially recognized ethnic groups. In 2010, 2022, and 2023, the 2008 ceremony still informed how Sha, Chen, and other ceremony directors must work.

In the aftermath of the 2008 Beijing Games, writer Liu Hongbo suggested that not only other opening ceremonies but all Chinese culture might have been captured by Zhang—The spectacle represented not simply the triumph of his personal vision but its elevation to a “national aesthetic” that became a measuring stick for culture more generally. Aspects of Zhang’s show gradually filtered into film and television, from local TV stations to CCTV’s annual Spring Festival Gala.

Before that, a prototype 2008 ceremony appeared during the 1990 Asian Games in Beijing. Held in the Workers’ Stadium long before its refurbishment (and 18 years before the Bird’s Nest Stadium was built), the ceremony featured little cutting-edge technology. After parachutists landed in the field, the audience was treated to a marching band performance ahead of the parade of competitors. Before the torch for the Games was lit, a multi-part exploration of Chinese and Asian culture was performed by dancers and acrobats, including a large-scale tai chi display with over 1,000 performers. The 1990 opening ceremony hints at what Zhang and others would pull off in 2008, but the lack of technological tools, as well as the rose-colored glasses of nostalgia, make it seem somehow more approachable, and more human.

But even by 1990, the invitation to participate that resonated from the 1959 National Games ceremony was already missing. While a role for local sports associations and amateur athletics has not entirely disappeared from events like the Olympics, the Asian Games, or the National Games, the 1959 documentary emphasizes a connection to the grassroots. In the shots of countryside athletes and kids at play, as well as the director’s interest in the model workers in the audience, there is the idea of the Games being at the center of a community, and the spectacle glorifying the health and prowess of the people.

Times have changed, of course, and the moment of children rushing around the stadium seemingly at random in 1959 probably couldn’t take place in the age of timed-to-the-second technological spectacles. But the cultural essence and “national aesthetic” of future performances will continue to evolve. Perhaps a new generation of young directors, raised in the digital era, will hanker for a return to more personal, inclusive, and chaotic ceremonies—an exciting prospect. As the slogan of the 1950s went: Long live youth!