Historian Duan Zhiqian explores road dangers and the emergent travel industry in China’s Ming and Qing eras

Modern travelers nowadays are lucky to rely on a range of safe, comfortable transportation to reach their desired destination—from high-speed trains to airplanes and everything in between. What’s more, we can count on many easily available sources of information to stay constantly updated on the specifics of our journey.

Granted, three years of the pandemic made us acutely aware of the privilege of unrestrained movement. But what about travel in historic times? What challenges did our ancestors face on the road, and how did their way of traveling differ from ours?

Today, our narrator is Duan Zhiqiang, a Fudan University history professor who hosted a podcast series called “Travel History in the Silver Age” on Vistopia, an audio, and video podcast app on art, history, and music. Through travel, the series explores the social structure and individual destiny throughout the mid-Ming (1368 – 1644) and Qing (1616 – 1911) dynasties. Let’s set out on this journey in time and space.

1

A Trip from 20 Years Ago

My name is Duan Zhiqiang, and I teach history at Fudan University in Shanghai.

I am a native of Henan myself, and my first proper trip from home was when I started university in Wuhan back in 1998. The elders in my village were impressed: “Oh, that sure is a big city.”

I had a tight traveling budget as a student. Once, I set out with three male classmates on a boat trip from Wuhan to Nanjing. Needless to say, we were all broke and went for the cheapest fare available. We’d assumed we’d get some sort of berth; little did we know that our ticket basically just allowed us to board the vessel—no beds for us, let alone cabins.

That autumn night, we found ourselves freezing on the deck. Eventually, we sought shelter in a small but toasty boiler room where we squatted until a crew member came to turn on the water in the middle of the night. He was startled. “What are you kids doing here?”

When we replied that we’d bought the so-called “steerage fare,” he was not very impressed. “Boy, are you kids dumb. Steerage fare for a long-distance trip. Alright, let me go find younitwits some seats.”

Eventually, we wound up in a third-class cabin for the night.

I was a northerner, born and raised on dry land. I’d never been aboard a ship for such a long trip, so I was thrilled and brimming with curiosity. It was all very impressive to me. This was back at a time when the Yangtze River Bridge in Jiujiang was still under construction. On a rainy day, the remote outline of the bridge, shrouded in clouds and fog, was quite the sight. When we came to port, merchants and hawkers came on board and peddled the wares that they toted on bamboo poles. We lived off their scarce offerings of tea eggs until we finally returned to Wuhan.

2

When Travel Was Forbidden

Story FM: Only 20 years have passed since Duan’s youthful trip, and already travel has changed beyond recognition. Now, let’s truly take a trip down memory lane—namely, to ancient China. What was traveling like back then?

Well, “control” is a good word to start with. There was also a turning point: the Song dynasty (960 – 1279). Prior to this, the state strictly controlled and managed the flow of commoners in society. With the Song dynasty came commerce, and the ever-increasing prosperity led to an incipient tourism industry. From that point onward, travel amenities such as inns and hotels grew in leaps and bounds.

But there’s an end to every golden period. This commercial revolution encountered serious setbacks in the Yuan dynasty (1206 – 1368), and issues such as population increase, land annexation, and famine eventually led to a serious refugee crisis. Into this unfavorable scenario came Zhu Yuanzhang (朱元璋), the founder of the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644) after the Yuan. In one of his signature policies, he renewed the strict control of the population’s flow.

Duan: The society that Zhu Yuanzhang envisioned in the early Ming was a tightly state-controlled machine, where everyone had a clear role to play and abide by—a role they’d inherit from their ancestors, and pass on to future generations. In this society, individuals’ autonomous movement was suppressed to the bare minimum.

Movement was still very common, just as long as it was arranged by the state, whether you were a soldier or a craftsman. The empire would ship you wherever you were needed, and your trip would go through its internal channels rather than the market. Everything was arranged in advance.

This rigorous system collapsed by the middle of the dynasty, when there was a gradual uptick in people’s independent mobility. The government also had to respond to the changing times with a series of reforms, enhancing the degree of commercialization and marketization of society.

Here, an important development needs to be mentioned. In the mid-Ming dynasty, a large amount of silver entered China from both the Americas and Japan. Compared with the paper currency used in the Yuan dynasty, silver was considered more trustworthy, thus providing sufficient and reliable currency for commercial activities. Markets, finance, mass production, and overseas trade all flourished right along with commerce. Thus came the so-called “Silver Age” —the period spanning from the mid-Ming to the Qing dynasty.

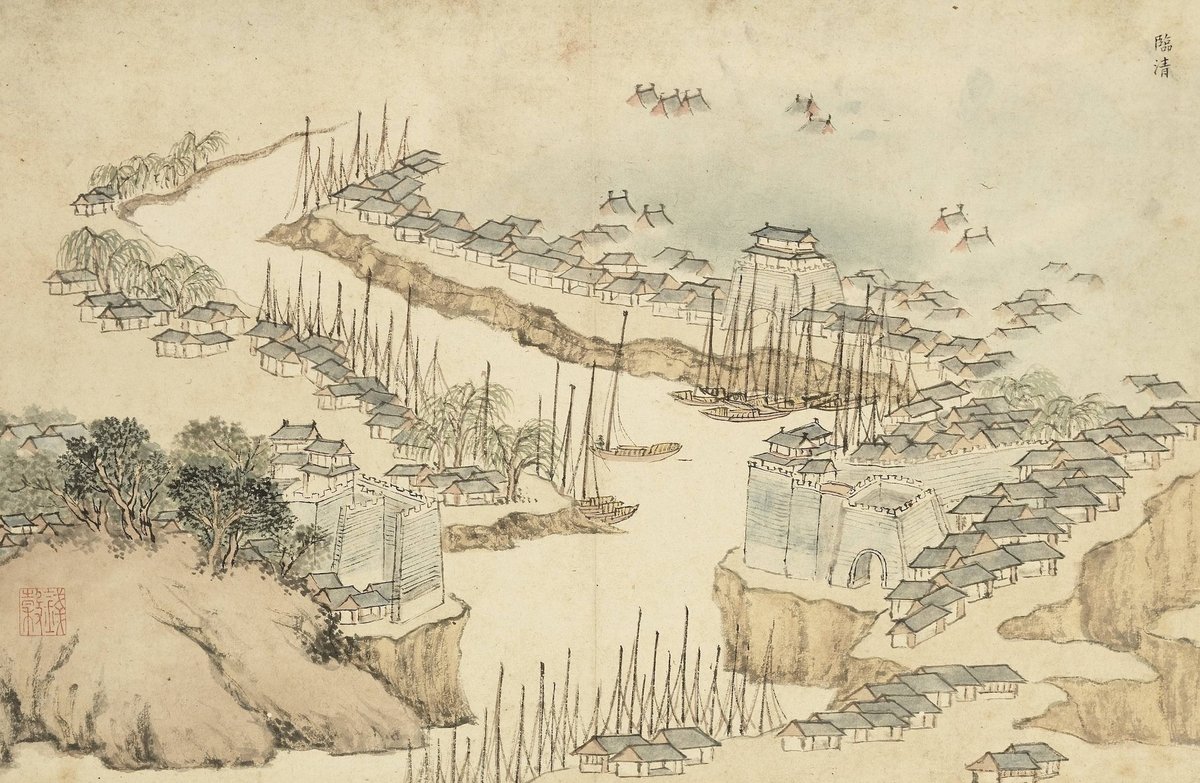

Earlier, the Yuan dynasty had begun a continuous stream of development for both the land and water networks, as well as a full connection between Beijing and Hangzhou by means of the Grand Canal. This all transformed the transport of the entire country. As a result, independent travel became a common occurrence from the mid-Ming onward. You may or may not exercise this right, but the possibility of travel was now at least firmly on the table.

3

Perils on the Road

When it comes to travel, our biggest difference with our ancestors is that they likely suffered significantly greater anxiety about the many unpredictable dangers they could face on their journeys.

For starters, mileage was nothing if not inconsistent. “Ten li” in one region may not have been equivalent to ten li in another. This was a serious problem. Misjudging the distance meant finding yourself alone in relatively remote places with no inns around. That was very dangerous for solo travelers.

It’s no wonder that fortune-telling books of yesteryear contained this question: Will a traveler safely return and when?

Mortality rates were so high among ancient Ming travelers that Zhu Yuanzhang arranged for so-called Lonely Ghost Temples (孤魂庙) that were to be built everywhere across the land to worship those souls that passed on while far from home. In wartime, most casualties were brought on by fighting; but traveling was the true grim reaper in times of peace. To this day, the Hongwu Emperor’s legacy of temples still stands for those nameless refugees, vagrants, and business travelers who came to harm and died on the road.

Travel guides would also instruct readers on dangerous roads and areas to avoid. I was really shocked to learn that scamming travelers was common practice on the road from Wuhu to Huizhou by cunning porters. Robbers also abounded. In short, it was dangerous out there.

Our ancestors’ worldview was wildly different from ours. Though we may not be aware of this, our modern world is highly systemized. When we look back at history, it’s easy to take an oversimplified view of it, because we have the benefit of hindsight. But actually, the standard practices and systems we enjoy now evolved through a long and rather arduous process.

4

A Travel Industry is Born

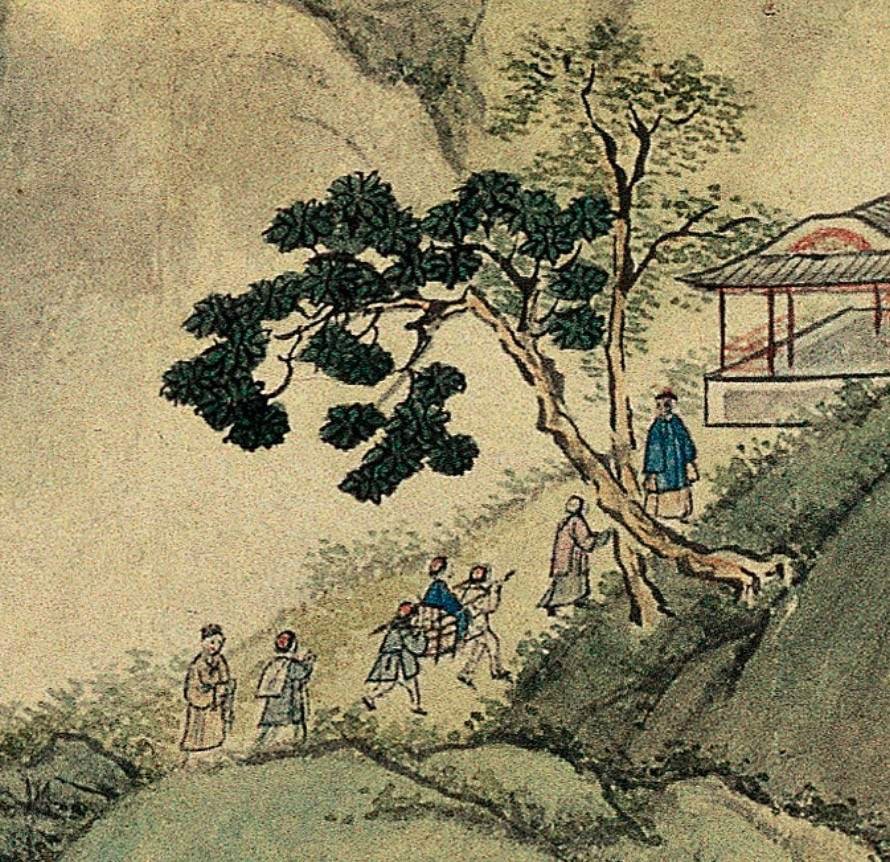

Story FM: Riding your donkey through the main traffic arteries of the Silver Age, you may have passed by plenty other travelers. Among the most majestic were the civil servants traveling to take up their posts or returning to Beijing to report on their work.

You were also likely to encounter scholars on scientific research duty, as well as businesspeople and merchants hailing from all over the country. The latter transported mostly basic goods such as grain, wood, and the oil from tung trees, which was used in everything from medicine to textiles to construction in ancient China.

This period already saw several trade routes emerge, such as the Ancient Tea Horse Road in southwestern China. For legitimate merchants, these routes likely provided some much-needed sense of security during their travels. Smugglers preferred offbeat paths to traffic government-controlled salt and other contraband.

Then, of course, you had those who traveled due to family matters—weddings, funerals, searching for relatives, and more. This category of travelers featured quite a few women and even elderly people.

Lastly, the roads swarmed with storytellers, entertainers, thieves, and all sorts of outlaws and outcasts of society whom you might come across, along with homeless people and refugees.

Duan: Besides the travelers themselves, ancient voyages also involved professionals who were involved in travel as an occupation.

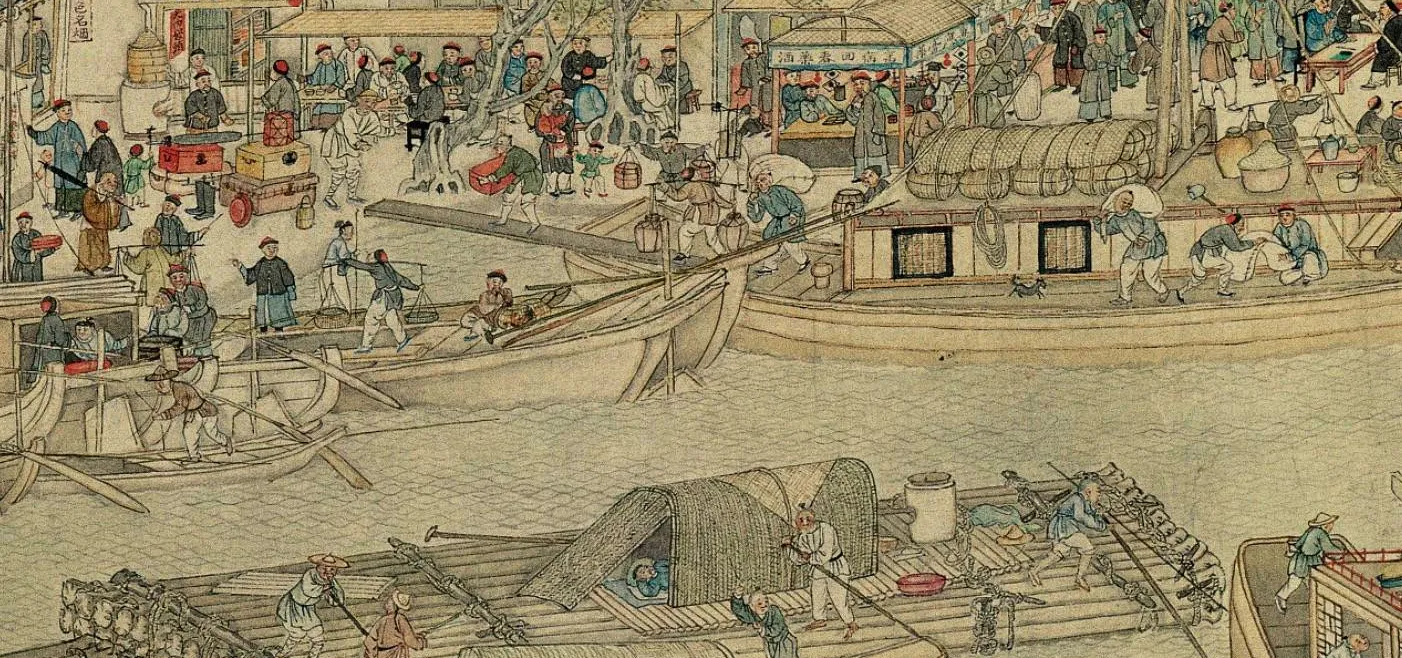

It’s enticing to imagine idyllic scenes of ancient travelers fanning themselves as they took in the beautiful vista from aboard their ship. The reality was less glamorous. Indeed they stood aboard ships, but rather messy ones where they could expect four-legged fellow passengers like dogs and pigs. It was not unlikely that the captain would try and extort you, either. Sailing on the Grand Canal also meant giving the right of way to official ships sailing the same route; if there was a traffic jam, you risked being stuck on the water for days.

The water level of the canal could be high or low. If it was too low, you needed to hire workers to tow the boat, and they would charge you by the mile. You may have to haggle over the price with them. There were also people tasked with maintaining the waterways, and though they had extremely low living standards, they played indispensable roles.

There were also brokers, who played similar roles to modern-day travel agents. From an orthodox view, these people were opportunists; though they also played crucial roles, they did not enjoy a good reputation.

The state was in charge of issuing licenses to these agencies. Pulling up at a pier, you may see a series of agencies lined up on the street. Some were licensed; some were not. Travelers could experience all sorts of crises on the road, including some evil boat operators who actively wished them harm; an agency stood as a guarantee against these mishaps.

Checking into an inn, you could also enjoy a series of services. Prospective climbers of Mount Taishan would find entire hospitality teams ready to cater to their every need, from food to lodging, incense offerings, and all sorts of leisure—proper and otherwise. Though our ancestors in the Silver Age didn’t enjoy our current degree of convenience, travel had definitely been made easier for them.

5

The Pleasure of Travel

The tourism industry was also a source of indirect stimulus for various other industries. One was the emergence of a special kind of vessel operating in the Qing dynasty at the Qiantang River Basin—the so-called “Jiangshan yachts (江山船).”

Jiangshan yachts—numbering over 2,000 in their heyday— transported people and goods, and were your best option for travel next to a government boat. What was different about Jiangshan yachts? Well, they were rather large, with a set-up featuring interconnected cabins for guests in the middle of the ship. The most bizarre aspect was that is that the door of this cabin could only be locked from the outside.

As it turns out, these vessels also doubled as pleasure crafts providing services of the flesh to passengers. The male staff took charge of transportation, while a team of women provided escort services. A popular saying at the time noted Zhejiang and Fujian had both turned into coveted travel destinations, if only because of the perks aboard the Jiangshan yachts. The Qing government was always cracking down on their activities, and yet there is a most famous, entirely true story related to these ships that has been preserved for posterity.

During the rule of the Guangxu Emperor, there was a high-ranking officer named Bao Ting (宝廷). He was a Minister of the Second Rank, the Right Vice Minister of Rites. He was also a member of the imperial clan, descended from a younger brother of Nurhaci, the founder of the dynasty. All in all, Bao Ting enjoyed a high social status and was known as a talented poet with sensitivity towards social injustices.

One year, Bao Ting was sent to Fujian to invigilate the provincial examinations. He took a boat ride on the Qiantang River and met a young girl during the trip. On his way back, Bao Ting suddenly reported himself to the Emperor with a memorial penned by his own hand.

In his self-criticism, Bao Ting openly disclosed his desire to take the young lady he’d met aboard a Jiangshan yacht as his concubine. Now, this was highly frowned upon at the time. Not only was such conduct scorned by mainstream society, but Bao Ting was also theoretically violating the law. In reality, it was hard to chase down all offenders, particularly if they were wise enough to keep a low profile on their romantic misdeeds. But here was Bao Ting proposing to bring his concubine to Beijing and even reporting it to the emperor. This made many people confused about his intentions.

Two years after Bao Ting was dismissed from his post, Empress Dowager Cixi fired a clique of officials over political differences, even exiling some of them. This was a major event in late Qing history. Bao Ting was able to avoid this purge, leading some to believe he’d deliberately sabotaged his career out of disappointment with society. Whether this was accurate or not, the incident turned into a bit of a legend.

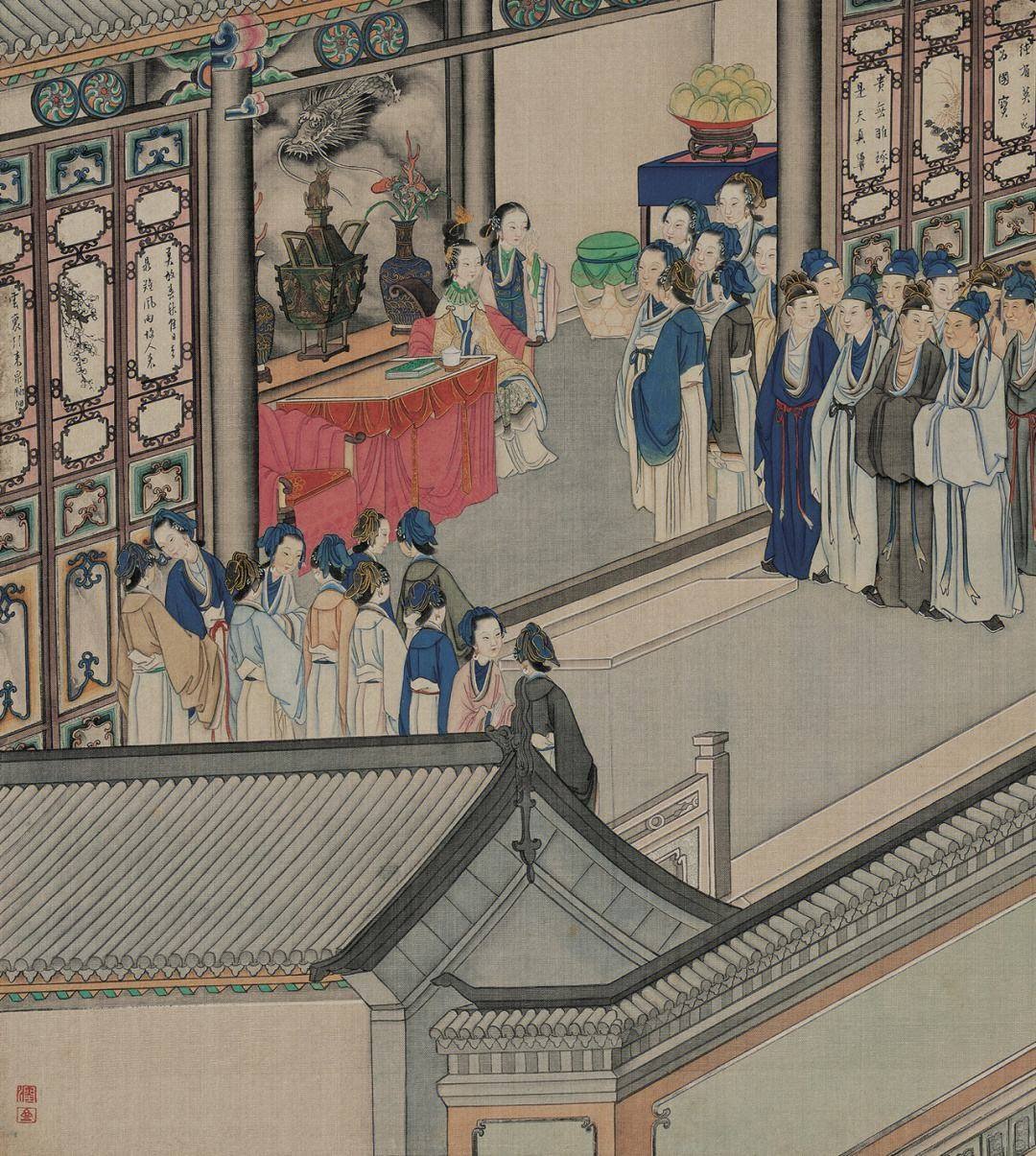

Many other ancient romance novels and plays are set in the context of travel. In both The Peony Pavilion (《牡丹亭》) and Dream of the Red Chamber (《红楼梦》), Du Liniang (杜丽娘) and Lin Daiyu (林黛玉) are both outsiders who suddenly arrive in the world of male protagonists, thus setting the plot in motion. Many industries of pleasure were also intertwined with the travel industry. For instance, candidates who came to Nanjing for the imperial examinations consorted in the pleasure quarters by the Qinhuai River, and many traveler’s inns were concentrated in Beijing’s red-light district, Bada Hutong.

6

Ancient Travelogues

We’re in no shortage of travel records penned by our ancestors. School textbooks today often allude to famous essays such as the “Eight Records of Excursions in Yongzhou (《永州八记)》)”, “An Account of the Old Drunkard’s Pavilion (《醉翁亭记》),” and “Night Tour of Chengtian Temple (《记承天寺夜游》),” all of them born from travels.

Literati were prone to delve mostly into scenery and emotions; detailed, objective travelogues were somewhat less common. Still, those records reflect the personal interests of their authors. They’re open windows for us to gain a vivid glimpse into daily life in ancient times.

For instance, let’s take a look at the travel diaries of Xu Xiake (徐霞客). He was passionate about geography. Thus, his explorations were peppered with geographical questions. How far did this mountain range extend? Is the origin of this river accurate?

We also have the records of Sakugen Shūryō (策彦周良), a Japanese Zen monk who authored an unusual series of travel notes in China during the Ming dynasty. He copied down every plaque and couplet he saw on the Grand Canal, down to the shop signs from local wine stores. This was something Chinese literati would not have bothered with. As a result of Sakugen’s unique notes, we gained insight into the kind of shops that lined the Grand Canal, the characteristics of shop banners, the couplets hung in inns, and much more.

Many also paid attention to local customs. Recently, I had the opportunity to read the 1882 travelogue of an American traveler to Hainan Island. Walking around, he soon realized that every inn on the island was run in a militant fashion by fierce female proprietors. In his travel notes, these women complained about their husbands being good-for-nothing slobs who did nothing but smoke and eat all day—and their appetites were fairly generous. . It’s no wonder these ladies were bad-tempered by default. When they served up a meal, they threw the pile of dishes down in front of the men, who would glare at them in response. Every inn on the island was like this, wrote the traveler.

And guess what—much like we snap vacation pictures nowadays, our ancestors paired their travelogues with illustrations that sometimes made up for most of the actual volume. In the Ming dynasty, there was a man named Wang Shizhen (王世贞), who became a high-ranking official and thus traveled from his hometown of Taicang to Beijing to take up his post. Wang found a painter to accompany him on his trip, who painted an illustration for each stop along the way. In the end, the duo came up with a series of 30 or 40 paintings in the style of their era that have been preserved up to our present day. Though they’re nowhere near as sophisticated as photography, they do provide us with a trove of visual knowledge.

7

Travel as Social Progress

We used to believe that ancient China was a society of low mobility, where men were irrevocably attached to the land and women were merely entrusted with birthing and raising children. The truth is that migration and social displacement were frequent occurrences over our long history.

If we were to explore our own family trees, we’d all be sure to find at least one instance of our ancestors migrating. I find that fascinating, because it goes to show that while most people would prefer staying close to home, real life will often prompt you to move, voluntarily or not, for various reasons.

For instance, there’s this story I shared in my show about a famous mid-Ming pirate named Wang Zhi (汪直). Wang had been born in the mountains of Huizhou and didn’t have a happy life at home. However, he was greatly ambitious. He’s quoted to have said that “China has fairly strict laws that limit all kinds of activities.” Wang yearned to display his many talents, except he constantly clashed against the rules. What’s a man to do? He took to the sea, following some friends to the Philippines. There, he built ships, sold sulfur, and eventually came into his identity as the pirate overlord in the waters of China and Japan.

We’re not morally condoning Wang’s legacy. But surely, you agree that he was quite the adventurer.

Many historical records also show foreign migrants seeking a new life in our land. We have an account of a man from the Korean Peninsula’s Silla Kingdom who migrated to China during the Tang dynasty (618 – 907). He was quoted to have said, “The people of Silla looks only at people’s bones”—that is to say, they were only concerned with a person’s rank by birth. If you were born into the noble class, you were bound to become an official, but those of low birth could never raise their social status. This man allegedly wanted to find his way in Tang society, where he believed he could rely on his own skills to either become a scholar via the imperial examinations or join the imperial army. The Tang dynasty did operate, to a certain extent, on a meritocracy. However, in the Ming dynasty, laws also became much stricter.

These two travelers were both fairly extreme examples. But my point is, that people of every era display a degree of intuitive knowledge about the society they inhabit. To gain social mobility, you must be willing to change your spatial and physical coordinates. Otherwise, you’ll find yourself struggling to overcome the restrictions in one place all your life.

Thus, traveling can be considered a crucial element in the functioning of a society.

8

Travel: A History that Belongs to Commoners

We know that famous travelers in history, such as Zhang Qian (张骞), Xuanzang (玄奘), and Zheng He (郑和), overcame physical dangers and their fears of the unknown, and were rewarded for their bravery by becoming the history’s archetype of pioneers.

But in fact, there are just as many instances of ordinary, nameless Chinese people who displayed significant ingenuity in order to survive far from home. Ming citizens from the Zhangzhou area, in today’s Fujian province on the southeast coast, are known to have “braved the seas as though they were visiting a town market”; and in the Northwest, along the Silk Roads, commoners regularly traveled for commerce; not to mention the existence of nomadic herding communities.

All these ordinary people remain unidentified by history, and their humble adventures—for instance, those of migrants who voyaged to Nanyang, or Southeast Asia—have been eclipsed by the grand accounts of a selected few. At best, they become part of the spoken folklore of certain ethnic groups who see their stories of resilience passed down in a vague, imprecise fashion from one generation to the next.

Each of our travel experiences is just as valuable as that of our most famous ancestors, and each of them is worth being recorded. I look forward to hearing more of these remarkable stories from my fellow commoners, because the more I read them, the more it seems that none of us are so different. We might exist in different environments in different chapters of history, but we’re all striving to live.

Produced by Ma Da (马达)

___

This story is published as part of TWOC’s collaboration with Story FM, a renowned storytelling podcast in China. It has been translated from Chinese by TWOC and edited for clarity. The original can be listened to on Story FM’s channel on Himalaya and Apple Podcasts (in Chinese only).