The answer is, of course, yes!

The recent live-action movie Barbie has become the newest sensation worldwide. Childhood fans of Barbie or not, everyone is excited!

Does China not have a Barbie to call her own, though? I couldn’t quite believe that our country, always famed for coming up with just about any invention under the sun, would miss out on the whole doll thing. Did our ancestors truly pass on dolls? Soon enough, my research allowed me to see that this hadn’t been the case at all.

Limited edition Qixi dolls

Look no further than the Song dynasty (960 – 1279) for the art of eating, drinking, and generally having a grand time. The rich and charming Eastern Capital of the Song dynasty (now Kaifeng in Henan Province) sure never lacked exciting novelties.

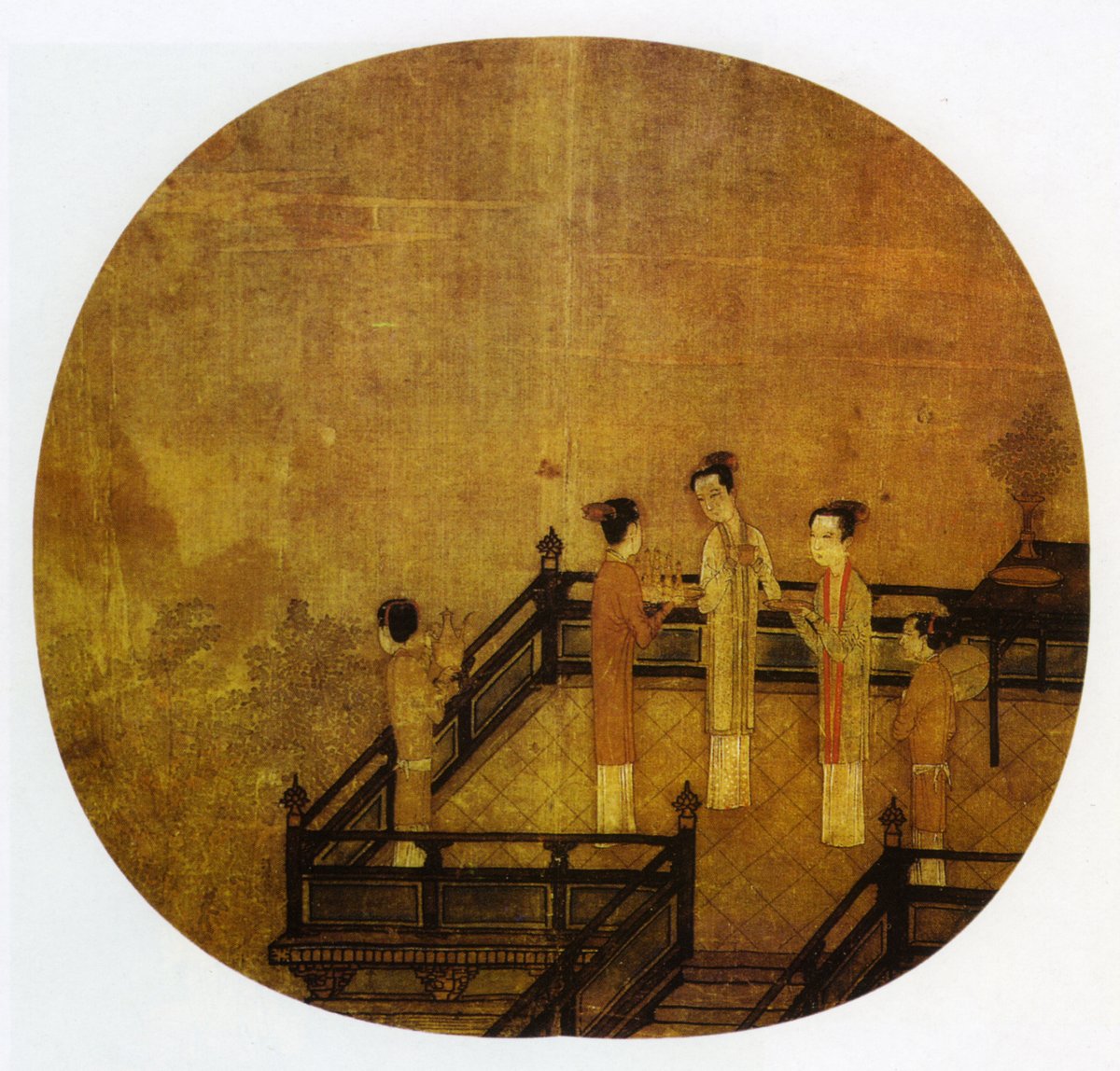

The Double Seven Festival, otherwise known as Qixi Festival (七夕节) or Chinese Valentine’s Day, was certainly no exception. Come the seventh evening of the seventh lunar month, rich and noble families would have their women gather up in the courtyard to “beg for skills in craftmanship” by performing rituals like threading seven needles in front of a special shrine. Here’s the thing, though—the shrines did not feature the Niulang and Zhinü duo, nor the Seventh Sister, the protector of all lovers, women, and children. Instead, they’d house a darling clay figurine of a child holding a lotus leaf.

This was, in fact, a sacrifice utensil commonly used in the Double Seven Festival to worship and pray for fertility. Though these were properly known as Mahoraga dolls, they had several Chinese names depending on the region, one of them being “Mohele (磨喝乐)” and its variant Moluo.

Certainly not a name that will roll off your tongue, although it carries echoes of Buddhism. “Mohele” is meant to be a transliteration of the Sanskrit Mahākāla, meaning “the Great Black One.” This deity is common to both Hinduism and Tantric Buddhism, with influences from the latter’s belief in hariti, or ghost mother. In the feudal Song dynasty, worshipping Mahākāla implied the longing for a male child.

Meng Yuanlao (孟元老), a Song dynasty prose writer, described in his famous memoir The Eastern Capital: A Dream of Splendor (《东京梦华录》) that on the day of the Qixi Festival, Mohele clay dolls can be found all over the city of Kaifeng. It’s almost like a big Mohele-themed cultural block! Safe to say they were the hottest commodities.

Mohele dolls may have been simple folk handicrafts, but their clothing was actually rather intricate. So we read in the Song dynasty title West Lake Old Man’s Record (《西湖老人繁胜录》): “[They were] mostly dressed in crimson vests and blue-green silk skirts; some were wrapped in beizi (褙子), and some wore hats.” Beizi is a type of swaddling coat worn by women in the Song dynasty.

Mohele dolls from the imperial palace were even more exquisite, both in terms of their material and attire. Again from West Lake Old Man’s Record: “Prior to Qixi, as a tradition, the Department of the Construction and Repair of Imperial Buildings would present to the court 10 tables of Mohele dolls, each table containing 30 dolls. A large doll could reach three chi in height (around 1 meter); some were carved of ivory, some made of ambergris and foshouxiang (literally Buddha-hand fragrance), while engraved gold leaves, jewels, and jade were used for all. Clothes, caps, coins, hairpins, bracelets, jade pendants, pearl-strung curtains, hairs, and the toys held in their hands were all made of the seven precious metals and gems, and each [doll] was encased in a five-colored, silk gauze cabinet embellished with engraved gold leaves.”

What’s more, these sources confirm that the dolls were then placed in an equally complex, highly decorative encasement. You can’t even find such lavish favors in modern times!

Whether humble or luxurious, the lovely image of Mohele has deeply touched our hearts. Children too began to cosplay the popular doll, as the Song dynasty scholar Zhou Mi’s (周密) volume Recollections of Wulin (《武林旧事》) recalls: “Young boys and girls often wore short-sleeved coats made of lotus leaves and held lotus leaves in their hands to mimic Mohele.”

Imagine during Qixi, the streets are filled with happy children holding fresh lotus leaves. You just want to go and squeeze their cute little faces.

The festival has become a celebration for children too. After all, these figurines don’t merely symbolize women’s longing for wisdom and fertility; they also represent the intelligence and vitality of children. So much so, a typical compliment for cute kids during the Song and Yuan (1206 – 1368) dynasties had people exclaiming: “Why, this baby is as beautiful as a Mohele!”—the modern equivalent of saying one’s baby is “cute as a button.”

Exquisite, high-end doll craftsmanship

Clay’s all fine, but what if the figurine accidentally drops and breaks, or even falls into the water? Fret not—our ancestors also came up with a doll made of silk.

Let’s trace back to Meng Yuanlao’s The Eastern Capital: A Dream of Splendor. According to this volume, folk artists throughout the Northern Song dynasty (960 – 1127) “cut silk in forms of people, tailor brocade for clothing, use colored silk and satin to form human shapes.” And, if we take a look at the small commodities and trinkets that one could shop for in the streets of Hangzhou at the time, we’ll find that there was a certain handicraft known as “silk babies (绢孩儿).” The popular puppet shows in the Tang dynasty (618 – 907) were probably the predecessors of silk babies. It’s also believed that the handicraft was inspired by caizha (彩扎) or zhizha (纸扎), an art of binding the skeleton using bamboo strips.

Silk babies have their bodies and faces carved in wood and colored before being dressed with silk, satin, and other fabrics. The end result does look like a miniature human who doubles as both a children’s toy and an indispensable companion for pregnant women who seek blessings.

Antique silk babies are a rarity because of their fragility. Fortunately for us, during the World Doll Exhibition in 1954, a woman named Ge Jing’an led a team of fellow artists in their careful attempt to recreate these silk figurines with traditional Chinese cultural features. Ge and her group’s initiative brought this handicraft instant popularity both domestically and internationally.

As the art of silk dolls gained significant development in Beijing and its surrounding regions after the founding of the People’s Republic of China, these dolls are also known as “Beijing silk figures.” Their metal wire skeleton is filled in with cotton to replicate the flesh, gauze, and silk for the skin, silk again for the hair, and brocade silk and satin for the clothing with multiple skills from sculpture, dyeing and weaving, painting and sewing to metal processing, paper pasting and filigree. Most of the time they represent heroines from Chinese classical literature, operas, and history.

Though it may look like a humble doll, it is actually an extremely delicate handicraft, with beautiful facial and hand features, retaining their grace and charm. Every frown and smile truly exudes elegance.

An ordinary silk figurine will take at least half a month to complete, and for the most intricate ones, we’re talking several years, even. Many will say that this is our Chinese “Barbie,” but looking at the exquisite, complex production techniques of these dolls, I beg to differ—Barbie could never! Would you like to know more about these silk beauties? Then head to the Beijing Silk Figure Museum for a thorough dive!

A Barbie of your own, wherever you are

One thing we must admit, though—the global influence of the Barbie brand is huge. In fact, its commercial success inspired many countries in the 1960s and ’70s to start producing their own versions of Barbie, such as MIMI Doll, created by the South Korean toy brand MIMI World. Its Japanese counterpart Takara (nowadays known as Takara Tomy), also obtained a license from Mattel to begin developing their own “Takara Barbie” in 1982, although the doll was later renamed Jenny in 1986.

In early 2001, Yue-Sai Kan, a Chinese-American celebrity, entrepreneur, and the founder of Yue-Sai Cosmetics, designed her own Wawa Dolls (羽西娃娃). Though their body shape was similar to Barbie’s, their features were distinctively Asian, down to their lush, smooth black hair and dazzling red lips, and fondness for earthy eyeshadow shades with calm and reflected looks.

The clothing design for Wawa Dolls carries the distinct marks of the turn of the century. Their wardrobe included loads of ethnic costumes, traditional Chinese attires like qipao, as well as the trendiest “hot girl” fashions at the time, such as crop tops, minis skirts, and short shorts. Rumor has it that many a mother passed down the Wawa Doll they got as a present from buying Yue-Sai cosmetics to their little girls.

After their launch in the United States in 2001, Wawa Dolls experienced quite a spell of popularity, even entering the largest children’s retail stores in America. All in all, they amassed some 350,000 dollars in sales. Wawa Dolls have been regrettably discontinued since, though you can still shop for them online if you’re seeking to relive a cherished childhood memory of the post-90s generation.

Not that the doll craze is going anywhere, though. From “Cotton Dolls (棉花娃娃)” to “Japanese Ball-Jointed Dolls (BJDs, most notably Blythe),” doll enthusiasts are in no shortage of charming and beautiful additions to their collection, which will often take priority over themselves for the most ardent fans.

Perhaps, just like in the Barbie movie, the birth of the first Barbie doll encouraged girls to dream about their own beauty. A doll might embody our “ideal life,” or perhaps it’s simply the “soulmate” for every child who lacks companionship. Both girls and boys can play with dolls, whether they are five years old or 50. Dolls are a storage compartment for our childhood innocence and ideals.

Written by Jing Jinbei (井今贝)

This story was originally published in Chinese on the public WeChat account of Bowu. It has been translated and republished with the author’s permission.