How a group of octogenarian opera singers tried to sustain their passion and a loyal community of opera lovers in a southern Chinese city

In December 2021, I watched an online documentary that a college sophomore named Qin Zijing had shot about a group of elders from the Wenyuan Guicai Opera Troupe (文苑桂彩剧团). Here, “Guicai” stands for two traditional genres of opera local to the Guangxi region—Gui Opera (桂剧) and Caidiao (彩调). The former is an exquisite craft relying on delicate facial expressions and body posture to convey a wide range of emotions. Caidiao was originally performed in pairs of the opposite gender. Later, it bloomed into a performance format featuring multiple actors onstage.

As I watched the documentary, I grew riveted by this elderly troupe who performed at their local theater almost every day, always on schedule. They’d been singing for four decades, taking only two days off per week. Their equally elderly and loving audience flocked to the theater, come rain or come shine. Now, these actors saw no money beyond the few yuan from their meager daily earnings. They performed for the love of singing.

However, there were no contact details online for these Guicai actors. Eventually, I reached out to Director Qin himself. He told me that the troupe had been disbanded in late November 2019, with a brief comeback in May 2020.

In January 2022, Qin and I visited Zhou Ying, the elderly lady who had been the troupe’s director. She gave us the news that Li Lizhu, the troupe’s head, had passed away just a week ago. Regrettably, for me, the troupe was disbanded for good.

For the next two months, I visited some of the former actors and their loyal fans. Eventually, I made my acquaintance with Zhang Fan, the documentary director for Phoenix Satellite TV. She, too, had filmed the troupe a few years ago and had a treasure trove of archival footage. Our acquaintance inspired me to bring back the stories of this group of elderly opera lovers, as well as their swan song.

1/6

Zhang Fan recalls it was raining heavily on the day she arrived in Liuzhou back in April 2019, on her first visit to carry out some research for her TV show Chinese Folk Opera. Camera in hand, her final destination was the Guangya General Market. Once there, she located an iron shed next to the public bathrooms. This was the headquarters and performance venue of the Wenyuan Guicai Opera Troupe.

It would be optimistic to call this dilapidated space a “theater.” On the day of Zhang’s visit, some overhead roof pipes had burst. Water gushed up like a fountain, washing over the stained tiles of the damaged wall and pooling on the ground. Next door, people walked into the public bathrooms holding their umbrellas and opened them again once they’d done their business and walked back out into the downpour.

Zhang was welcomed into the theater by Li Lizhu, a slightly stooped lady dressed casually in white, who came out armed with a broom. Back then, she was still the deputy head of the Wenyuan Guicai Troupe. The rain had interrupted her makeup session, and now she growled as she swept up the water: “What rotten weather.”

With the sky dark due to the rain and the theater’s dim lights, you could hardly tell the time. A black ventilator stood by the door, while a memorial tablet for Emperor Xuanzong of Tang hung on the wall with a few burnt incense sticks. The legend has it that Xuanzong was a keen drum player and played the role of xiaohualian (小花脸) in Peking Opera. Legend said that he and his ministers would enjoy opera inside a pear garden, and thus “pear garden (梨园)” became a shorthand for the whole realm of Chinese opera.

Opposite the censer was a dim stage dressed in yellow silk that had been lifted to reveal the large red backdrop behind. On the stage, there was a table flanked by several chairs. The auditorium was a humble bench placed below. A sign on the wall had a call for donations in red and black characters.

The backstage area had somewhat better lighting, even if by means of a bunch of electric wires pulled at random. Particles of dust floated by the light of a naked light bulb hung beside the dressing table. An assortment of photographs from past performances was on display under a glass sheet on the table. The wall was lined with peeling cabinets piled with flower boxes. The oily scent of face powder and paint lingered in the air, and some clothes hung from a wire in front of the table. Several exhaust fans had been installed around the shed, and a white suspended ceiling hung from the roof. Two dead clocks hung on the wall, completing the scene.

On her third day of shooting, Zhang Fan met an elderly lady everyone called Zhou Ying. Pointing with a pen at a sheet of paper fixed to the wall, she was taking her sweet time giving the troupe instructions for the day’s performance, needing to sit down every now and then. It was only then that Zhang realized this energetic granny was the director of the troupe, who still showed up at the front lines of production every day at 82 years of age.

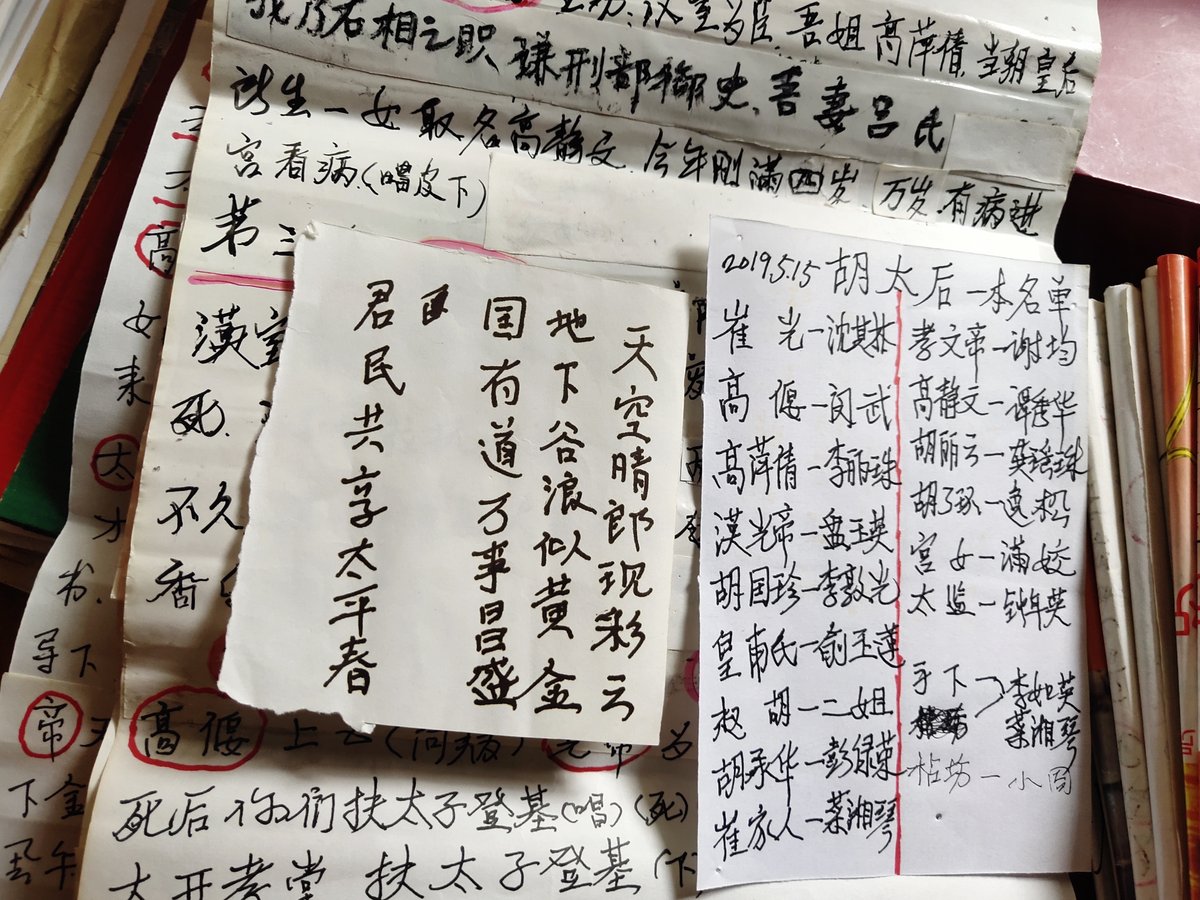

Zhou always carried a backpack, where she kept the opera scripts she’d penned herself. She would arrive an hour before curtain, fumble with a large pushpin to fix the instructions to the wall, and give everyone the information on the performance that day: what the punchlines were, who would play each role. No detail escaped her.

A corner on the right side of the stage was assigned to the band. The qin and erhu were packed in their bags, while the large and small hall drums were spread out to allow their surfaces to dry. Bells stood quietly aside. The musician would arrive, holding a blue plastic cup in his hand that he would sip from before leaving it on the edge of the stage and lighting himself a cigarette. The smoke coiled upwards around the climbed up around the music stand.

The actors dealt with the trembling of their old hands by picking up their hand mirrors and keeping them close as they put on their makeup. Just behind, a dusty framed poster in the style of the “Modern Girl” of the early 20th century seemed to stand witness against the ravages of time.

The audience trickled in. Some walked with canes, and many sported gray hairs. The performance was about to start.

2/6

The troupe moved into the Guangya General Market in the summer of 2016. They fashioned a theater out of a former warehouse. In the sweltering summer, inside that 200 square-meter iron shed next to the public toilets, they were soon drenched in sweat. Each performance was preceded by a vial of Huo Hsiang Cheng Chi Shuei, a popular Chinese herbal supplement.

The troupe honored the tradition that a new stage must be inaugurated with a performance of Killing Three Demons (《斩三妖》). The audience had already dispersed on a certain afternoon at 4:30 when the troupe filed over to the bathroom next door to remove their makeup, towels, and washbasins in hand. Li Lizhu sat backstage, amid a sloppy mess of piled stuff on the sides. To save the trouble of organizing, the troupe covered up the mess with blankets. However, Zhou Ying suddenly slipped on one of those blankets and almost hit her head on the bench. She was still holding her washbasin.

Startled, Li hurried over to help her. ”Big Sis, what’s wrong?”

“It’s okay,” Zhou replied, still sitting on the ground. “I’m fine.”

Zhou had just scratched her palm. Years ago, she had warned her daughter, “If I croak in the theater, don’t even bother bringing my body back home. Just take me straight to the crematorium.”

Li herself kept a stack of liability waivers on her table for the troupe and audience to sign and ensure that no relatives could hold the theater responsible for whatever misfortune took place there. She and Zhou had known each other since 1952 when the country recruited Gui Opera interpreters from all over rural Guangxi to perform in the countryside in Liuzhou for three months. Back then, Zhou was 15 years old and playing the role of a white-haired lady. Li was one year her junior. Both spent their breaks frolicking on the grass and quickly became bosom friends. A third member of their sisterhood, Sai Chang’e, had died years ago.

When the program ended, 16-year-old Zhou briefly returned to her native Guilin before being relocated to Nanning, the capital of Guangxi, to join the provincial theater troupe. Li stayed in Liuzhou, where worked for a while in a department store. She was in her 40s when she started joining opera performances again in Yufeng Park at night, at a time when the glory days of singing revolutionary “model operas” had passed and Gui Opera caught once again the attention of the public. This is how a bunch of retired actors made their comeback to folk theater under the banner of the Wenyuan Guicai Theater Troupe.

With the 1980s on China’s doorstep, youths were more than happy to dance to the rhythm of new trends, rocking flared trousers to the movies, and listening to pop music. Liuzhou, too, continued on its path to modernity, though this was bad news for teahouses and traditional theaters. Lacking a permanent venue, the Wenyuan Troupe was lucky to rely on their supportive audience to come to help them carry their tables, chairs, and cabinets as they migrated from one dance hall to the next.

It was then that Li invited Zhou, now freshly retired from opera school, to join her troupe. Li held Zhou in great regard. “She used to be a national first-class actress who could handle any challenge onstage, so good at singing the xiaodan (young female lead). And she’s still in good health.”

After all, theater was in Zhou’s blood. Her father, Zhou Wensheng, was dubbed the “King of Xiaosheng (小生),” famous for singing a male role in Chinese opera known as “little (gentle)man.” Her mother, Tao Hongju, was a famous socialite in Guilin. They mingled with the likes of Yan Jinyan, known by his stage name of Feng Huangming and famed in the 1920s as the first of the four famous dan opera singers in Guizhou Opera. It was under his expert tutelage that Young Zhou Ying started learning Kunqu opera at the tender age of 9. Her training would then continue with actor Liu Chuanheng.

Zhou usually gave instructions from the Wenyuan Troupe from a corner near the stage’s edge. Once, she fell and rolled down the steps. She owed her crooked back to the mishap. She was not able to stand for a long while without her legs getting sore, but sitting down didn’t bring her much relief either. Eventually, a hospital examination revealed that she required surgery for three of her intervertebral disks just above her waist.

Zhou carried a strenuous daily practice, getting up bright and early in the morning to train her voice and stretch her muscles. She may have shed tears from the pain, but she wouldn’t ever cry out. The troupe staged each play for a total of three months, and Zhao Ying trudged along, refusing to tend to her back and worsening her old injuries.

In 2017, 80-year-old Zhou Ying was hospitalized six times in five months, including three rounds of surgery for her ailing back. The first operation concluded with a spell of ten days resting at home, but she ended up back in the hospital for further surgery. She got tearful visits from her audience, unable to hold back from reminiscing about the old times. “I still remember you onstage back then…”

She’d been an unstoppable force of nature for so many years, but not anymore. Now she was a rail-thin elderly woman who couldn’t even stand for five minutes. Her hair was falling out in handfuls, too.

“Stop recalling the past,” Zhou advised her visitors. “And don’t you cry. I’ll be just fine.”

Standing up was still out of the question even after the surgery, so her exercises were constrained to whatever she could do while holding on to the wall. Small slips she could handle, but she still sustained three serious falls. Pain was thwarting the willpower of the ever-stubborn Zhou Ying to carry on. In the past, if you called “Principal Zhou” from downstairs of her apartment, you could see her dashing downstairs from her sixth floor, and then back up again, as though she flew rather than walked. Now, she dragged herself from floor to floor.

Zhou Ying’s days on the stage were past. Instead, she focused on her work backstage, though working on scripts was no walk in the park either. She had to read plenty of story books, do her research on TV dramas for inspiration, and pour over her outlines. When she was getting ready to leave the hospital, she’d rushed to stop her daughter Yu Fang from discarding a martial arts novel next to her pillow: “No! I still need it!”

She suffered from rheumatoid arthritis and joint pain that had weakened her hands and made a true challenge out of holding the pen as she burned the midnight oil to work on her scripts.

3/6

At only 50 years old, Min Wu was the youngest actor in the troupe.

Zhou Ying giggled when she recalled the first time she met Min, when some members of the troupe had gone to Guilin to recruit new blood. As soon as he sat down, the whole troupe was sold. The kid had been clearly born to play the hualian (花脸, “painted face”) role. “He was this plump, serious kid. Quite amusing. We had him sing a few lines, and once he was done, he bowed to all of us.” Zhou Ying got quite emotional when recalling her first impression of the now gray-haired Min. “He’s been like that ever since he was a kid.”

Min had graduated from an opera training school and joined the ranks of the Liuzhou Gui Opera Troupe. Later, he was invited to sing in the Wenyuan Troupe. It was a change from the proper, stricter ways of his former company, and Min wasn’t all that impressed. He complained privately to another senior actor that the freestyle modus operandi of the Wenyuan Troupe was “quite unprofessional.”

“Don’t you know just how old they are?” the other actor asked him. “Sure, they can no longer do somersaults like you, but do you realize what a big deal they were in their youth?”

Indeed, most of Min’s fellow actors had a background in professional theater. Former belle Ma Wanyu, for instance, had been a “national first-class” actress gifted with a fine voice. Later, she underwent back surgery twice, as well as another round of operations for her neck. She’d chat with Zhou Ying about the “first class” osteoporosis they jokingly said they both suffered from. Zhou’s was bad enough that she could compare her bones to a fishing net, but Ma fared even worse. Xie Jun, a “national second-class” actor who’d joined a professional troupe at the age of 13, had injuries all over his body from years of dancing with daggers and guns onstage.

The 30 actors in the Wenyuan Troupe had amassed quite a history of medical emergencies, from stroke to cancer, not to mention loads of injuries. More often than not, several people would be missing from the cast, whether it was due to errands or a doctor’s appointment. Min Wu, in his salt-and-pepper hair, no longer the solemn kid from three decades ago, always came to the rescue when there were roles that needed filling,

Many of the eldest actors also ended up passing away, though plenty of them were active through their final days. Such was the case for former troupe director He Peilan. On a fateful Sunday, she’d paused onstage and turned to Li Lizhu. “Hey, Li, I feel a little off. Think I’ll have to leave.”

“Off you go,” Li Lizhu readily agreed. “I know the script well. I’ll take care of everything.”

The next day, Li’s phone rang: “He Peilan passed in her sleep at 8 a.m. this morning.”

Her passing was so sudden that nobody could believe it. It was also on a Monday, one of the troupe’s only days off, and Li couldn’t stop fixating on this detail. In her mind, He Peilan never got to enjoy her day off before departing this world.

Then there was Gong Yaozhu, born to an operatic family and known by everyone as Third Sister. Her actual sister had been none other than Gong Yaoqin, a famous Gui Opera actress who died by suicide after being wronged during the Cultural Revolution. Third Sister moved to Liuzhou with her husband in her youth and started singing with Li Lizhu upon her retirement. She’d suffered several strokes and her hands and feet no longer fully obeyed her. When putting on her makeup, her hands shook so much that she couldn’t even draw her eyebrows right. But she still made it to every single performance.

That day she was acting as an imperial bodyguard. She put on her makeup while the rest of the troupe chitchatted about strokes. You’d think they were talking about the weather, and Third Sister recalled her own attack as she reached to her eyebrows: “It was a real mess when I was in the hospital. I couldn’t speak well.”

Li Lizhu chimed in, “Yeah, because your brain can no longer handle speaking.”

“In fact, my throat is worthless these days,” said Third Sister. Still, she started humming. Li, listening by her side, tilted her head and encouraged her. “Yes, that’s right. Why not sing louder and see how it goes?”

Third Sister cleared her throat and turned the volume up, trying to hide the burden of her advancing age in her rendition of an aria from The Legend of the White Snake (《白蛇传》): “With both their swords unsheathed, the monstrous duo of green and white snakes cast a death sentence on the bald-headed donkey now.”

Li chimed in until she sighed with a guilty smile, “I’m out of breath.” Both women laughed together.

Li’s biggest struggle was troupe members not being available every day. They used to have a regular musician in the troupe, but he deserted them after a dispute. Li had to find a replacement, except that one too fell through, so she was forced to make up with the first guy.

However, she wasn’t always that lucky. With a dwindling number of actors, one person was often forced to play multiple roles. Such was the case of actor Zhong Nianying, who switched from a maid into a robber in one show, jumping from one costume to another half a dozen times. But those who stayed with the troupe were committed to it. Actors were known to have rushed out of the hospital with needles barely out of their veins to go back to the stage after a bout of fever.

Looking at these elderly ladies and gentlemen, director Zhang Fan often thought of Gong Er, the stubborn female lead in The Grandmaster (《一代宗师》). Much like her, they too lived in their own timeline along their sparse but enthusiastic audience. Here, Gui Opera had carved itself a small shelter away from time. Zhang was a guest to these people and their drama, both on and off the stage. It was their show.

Li Lizhu was in poor health herself. She’d suffered from gout and rheumatism for the last three decades, tossing and turning in bed at night from the unbearable pain. She couldn’t walk. She couldn’t hold a thing. In fact, she couldn’t even write much nor put on her makeup. But her spirit still soared onstage.

“I don’t know just how much longer I can last” Li admitted. “So, I’ll just go on for as long as I can. As long as I live, I can’t stop singing.”

4/6

The theater troupe had always operated without government support. Though they were entitled to some state grants and corporate subsidies, the funds were barely enough to cover the costs of moving, renovations, and costumes.

Tickets were originally priced at 3.5 yuan, though, with fervent support from their audience, they raised them to 5 yuan after moving to the Guangya Market. In fact, spectators donated money every month of their own accord to subsidize the troupe’s operating expenses, covering the rent for some venues. Any extra money was on the actors to cough up. Their current venue at Guangya was a true sauna in the summer, so Zhou Ying spent over 10,000 yuan out of her own pocket for insulation.

The troupe knew a total of ten venues over the years, pushed around by rising rent, building requisitions, and concerns over safety or accessibility. After all, their audience, much like themselves, were too old to get around easily.

One thing is for certain—the audience’s love and appreciation did keep the troupe going for many, many years.

The troupe sang for 13 years at the Shuiren Machine Factory on Rongjun Road. Fifth Sister-in-Law, one of their most loyal spectators, found the venue. She lived far away and was bedridden twice after a stroke, but her love of theater had her drag herself to each and every performance. Sometimes, she’d wait alone at the bus stop in vain; drivers passed by without ever stopping at the sorry sight of her elderly frame leaning on her crutches. She’d leave her house at 11:30 and arrive at the theater at 2. She needed someone to assist her in walking, so this other lady, Ms. Lu, often sat next to her, and the pair helped each other out once the performance had finished.

Early on, the troupe had some invitations to perform in places where the organizer could only provide accommodation. So the actors relied on the audience to follow along and buy them groceries, even helping them cook.

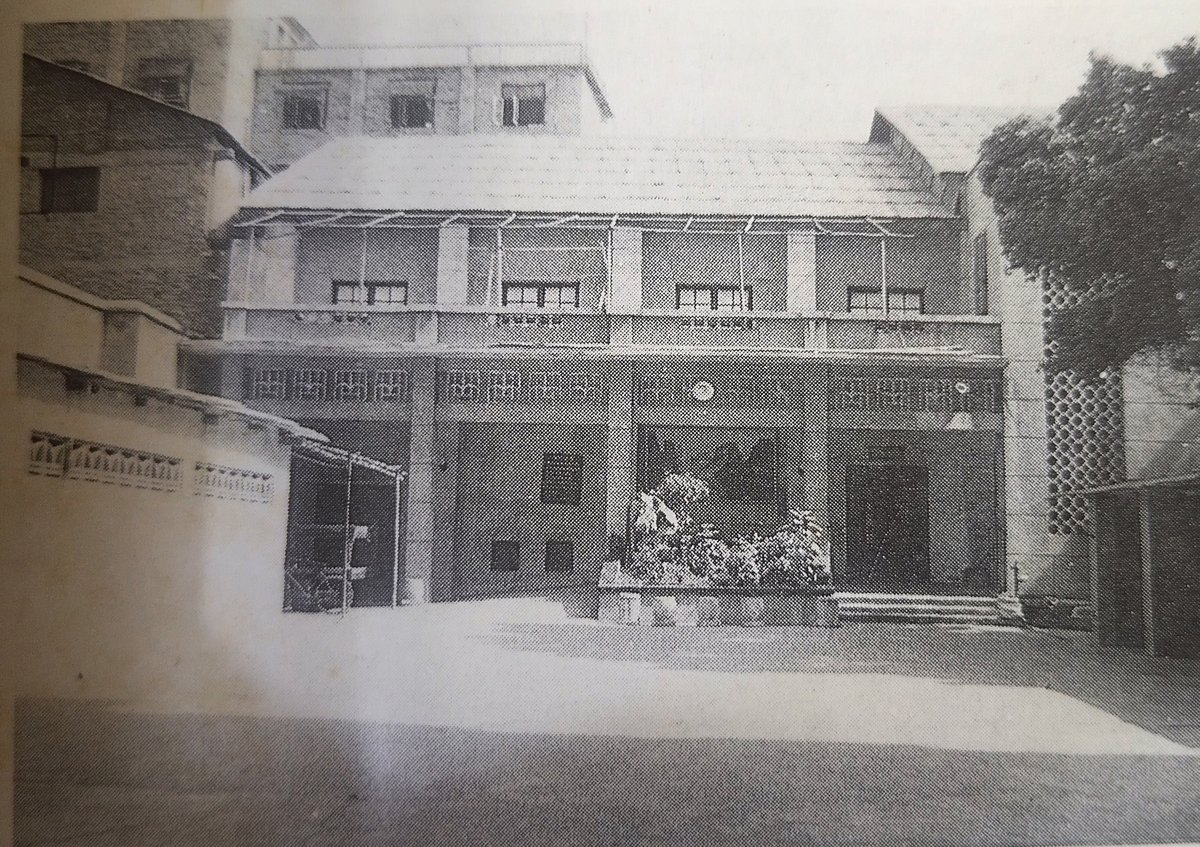

The troupe performed in an old building prior to their move to Guangya Market. The theater was on the third floor, and the elderly crowd had to grip the stair rails tightly as if climbing up a rope. Random sofas and benches donated by different households were arranged in a row and the elderly audience plopped down on their seats. Some ate their boxed lunches, while others dozed off and some chatted. Yet others squinted their eyes and listened to the opera. One thing was for sure: swapping snacks came first for the audience. Their bags were like on-the-go grocery stores. They saved the steamed buns, zongzi, and tea eggs for the actors. With their old buddies, they’d share an assortment of walnuts, red dates, rice crackers, and melon seeds.

Fifth Sister-in-Law would sometimes call Li Lizhu before arriving: “Sis, how many people are there today?” She wanted to know so that she could buy enough zongzi for the troupe.

“Enough that everyone does get their share,” Li would reply, laughing.

And so, Fifth Sister-in-Law would always get proper acknowledgment before each performance: “Our gratitude today goes to Fifth Sister-in-Law, our rice dumpling supplier.” Li recalled, “We knew they’d feel flattered by this small courtesy.”

In fact, the whole audience took turns buying food for the troupe, as though they’d made a promise to keep the actors fed. And with full bellies, the troupe always made sure to thank their benefactors onstage.

Zhou Ying attested to their audience’s loyalty: “They just keep coming, no matter the weather.”

It rained an awful lot in Liuzhou. It had been raining non-stop since April. That summer, the rain was heavier than normal, often alternating with thunder and lightning. The sky darkened and seemed to be torn apart, and it felt like a river was pouring from a hole onto earth. Once, during the downpour that made the theater roof crackle, the troupe arrived for work shaking the wind and rain off their bodies before walking inside. Only some seven or eight spectators awaited them.

The actors asked Li Lizhu whether they’d still stage a performance that day.

“Even if only two people come and don’t pay, we sure as hell will,” she said.

Many felt that Li was going too far with her insistence that the show must go on. “Why, be our guest and starve yourself onstage, you old stubborn mule! Just don’t drag us with you.”

Li could not care less. “Nonsense. So you lot really plan on sending your audience back home empty-handed after coming all the way down here?”

Zhou Ying seconded her just as firmly. “Quit the whining already! These old folks came here with their walking sticks under the heavy rain and you all got the nerve to try and cancel the show? Do you truly cherish Gui Opera? And you want to let them down? Shame on you.”

With that, Zhou went out and reassured their scarce audience. “Sit down, please. Your seats are booked. The two plays today are on the house, as long as you remember your date with us tomorrow.”

The rain was only getting heavier.

The theater’s manager was Zhu Mingtian. He was in charge of booking venues, folding costumes, boiling tea, and just about anything else you may think of. He was a tall and loud gentleman in his 70s, and when he talked onstage, his voice boomed all over. “Ladies and gentlemen, the grand finale of the Legend of the Three Sisters is about to start.” Zhu would briefly pause here to count heads before bellowing again: “Just some eight or nine people today!” Then, he’d slip backstage again.

Slowly but steadily, the audience showed up and the troupe ended up selling over 60 tickets that day.

Li was pleased. “They just keep flocking here the more it rains. We must be some fun after all.”

However, two hours later, the rain had yet to stop. Zhou Ying was less optimistic: “Very endearing, but we’re in a real pickle now.”

Backstage, actors left one after another as soon as they’d removed their makeup. Manager Zhu passed something to Li across the table, but her hand couldn’t make contact. It took the pair a couple of seconds to realize their hands were still far apart.

“Rats, I just really can’t see a thing with this blind eye of mine,” Li Lizhu lamented.

Zhu asked, “So what business do you have to sing when you’re blind already?”

“Well, I’m not singing with my eyes, now, am I?” Li glanced at Yu Yulian, still busy removing her make-up. “Now look at Yulian’s bulging eyes. Don’t they stand out? The girl got the best eyes in the troupe.”

Yu smiled at Li’s teasing. Zhu’s sharp tongue did not miss a beat. “Why don’t you buy yourself some carp eyes for a snack? Nine hundred yuan a catty.”

“Reckon I’ll go for pearls,” Li Lizhu took off her wig. “Now, you take care of this.”

One afternoon, the power suddenly went out all over the market and caught the troupe mid-performance. The only warning they had was a visit from market staff minutes before the switch was off.

Li Lizhu stood in the darkness for an hour as she waited for updates that never came. She could only distinguish the outlines of the audience and their shadows as they walked back and forth. Though everyone rushed to buy candles, nobody could light them up. This one time, Li agreed that they might as well call it quits and try again the following day.

But the audience would not have it. “Who cares about the darkness! As long as we can hear the singing, it’ll do.”

“But you won’t see our faces” Li pointed out.

The spectators insisted that they could not care less.

At Guangya, the bottom of the stage was made of wooden boards that looked fine on the surface but had rotted long ago. Therefore, some boards were higher than others. The audience knew this and warned the actors to stay vigilant: “Be careful when you enter and exit, the stage is uneven and it’s all dark.”

Faced with this unique relationship with their audience, Zhou Ying sighed endlessly at their kindness. After the performance, she felt obligated to treat them all to dinner. Those days, longtime supporters of the troupe who were now confined at home due to illness or age still called her in tears: “Oh, Ms. Zhou, I want to go to the theater.”

5/6

Director Zhang finished shooting the troupe’s daily routine and headed to Zhou Ying’s house to look at some old photographs and shoot there. Zhou’s family lived in a compound for cultural workers, along with many former theater troupe members.

Zhou dug out a stack of photos that she passed to Zhang Fan. “Either you take them away or I’ll burn them.”

Three years ago, Zhou received a letter from an old couple who had once briefly visited Liuzhou, and recently heard that the three major theaters—Liuzhou, Dongfeng, and Red Star—were gone.

Long time no see, comrade Zhou Ying! We’re an old couple in our eighties, and there’s no hope for us to return to Liuzhou. But we did come here on the occasion of our retirement, over two decades ago, to watch Gui Opera. This joy has now also been taken away from us, as we’ve learned that the three major theaters have closed their doors. We’ve heard that you are still alive, though some of the old actors have already passed. It’s our hope that this letter will convey our wishes for your good health.”

Saddened, Zhou Ying burned the letter.

Many elders visited Zhou to drink tea and lament over the old days. But Zhou always cut them off. “No use in talking like that.”

Zhou was of the opinion that a person can only keep on going if they leave behind the past. Back in the day, people would line up to buy tickets for the Lunar New Year performances, which played over the whole month, and peddlers hummed the tunes as they rode their tricycles down the street.

Back then, the cultural workers’ compound where Zhou lived was always lively. There were four rehearsal halls, each assigned to a different genre—Gui Opera, Cantonese Opera, Caidiao, and the Song and Dance Troupe. The bell rang in the courtyard at 8 in the morning, sending actors out of their homes and toward their rehearsal spaces. Gongs and drums echoed from the rooms onto the courtyard, where you could always find someone warming up their voice next to someone stretching their legs, while others danced with batons and practiced somersaults without ever disturbing one another. The noon hour was invariably serenaded by classic Gui Opera arias played on the radio, and evenings were reserved for performances.

“Now I sit at home and it’s always a wild guess with the rehearsal space. Sometimes they’re busy, sometimes empty; sometimes lively, sometimes quiet.” Zhou was a little disappointed. “Actors from Guilin want to come here to perform because it’s all over for them there. And soon enough it’ll be over for us here, too.”

So this is how Zhou went about her memories. The letter was burned, the photos were given to Zhang Fan, and if it were up to her, none of her scripts would survive her either.Every time Zhang came to shoot, she witnessed Zhou working on her scripts and discarding them as she wrote. Min Wu sometimes stopped her: “No, don’t burn that one. Just put it over there.”

Zhang, too, would sometimes rescue some discarded script from the trashcan whenever Zhou Ying wasn’t paying attention. Gradually, she grew attached to these elders. Even after her filming officially came to an end in April 2019, she still returned three times to Liuzhou that very same year—this time, to record more footage for the sake of the elders themselves.

In July 2019, Zhou Ying was busy writing a script for Untying the Red Silk Knot Back-Handed (《背解红罗》) to honor the promise she’d made to Fifth Sister-in-Law, who longed to see this drama onstage. She got as far as the fifth volume before another fall during an exercise session at home landed her right back in the hospital.

Then came two bouts of pneumonia in September. Zhou had to stay in the hospital during the first bout, and sent her regrets to Fifth Sister-in-Law via Min Wu, though she was resolute: “As long as the troupe still stands, you will get your play, even if I am not there.” She doubled down on her message through Li, too: “Will you tell Fifth-Sister-in-Law that I am really sorry?”

One day, Zhou waited for a long time, wheelchair-bound, outside the clinic where she was meant to undergo an examination. When the doors finally opened, Zhou went in and found none other than Li Lizhu, checking in herself. Li had arrived at the clinic just a day after Zhou. Now, their beds were next to each other. Later, Li recalled the fun of it all: “What a coincidence it was.”

In Li’s case, it had been a sudden heart illness. Her heart could seemingly no longer beat by itself; her chest was tight and her breathing cut short whenever she tried to talk too much. An electrocardiogram revealed her blood was no longer dense enough in nutrients to nourish her heart. The doctor, alarmed that Li could be at grave risk without supervision, ordered her immediate hospitalization.

Unfortunately, nine days later, Li couldn’t claim to feel any better. Not only did her chest still hurt, her heart rate couldn’t go back up and her back had started tormenting her again at night. She had to go back to the hospital, and that’s how she found Zhou Ying there, with both her hands already bruised from needles for her treatment.

On the evening of September 28, a shivering Zhou Yin had sat in her living room area. By 3 a.m. three o’clock in the morning, she was soaked in her own sweat and her throat raged. The nanny in charge of her care had left, so Zhou could only stay in bed, half gone already until the couple across the hall took her to the hospital.

As it turned out, Zhou Ying had a habit of circling days off on her calendar. The circle she drew on September 28 was almost her last one.

When Director Zhang returned to Liuzhou to visit Zhou Ying, she found her lying on her hospital bed, shrunken to skin and bones. Zhang wanted to take a picture with her before leaving, but Zhou refused. “Just leave. I won’t take a picture with you.”

Still, Zhou Ying had it in her to comfort Li at the hospital. Li was anxious about the future of the troupe. In autumn, Second Sister called her: “No performances yet? It’s getting cold.” From May to October, the sweltering weather forced the troupe to suspend their performances, though rent was still due by the end of that year.

Li kept tossing options in her mind. Should the troupe stay at their current venue, or move again? With Zhou offstage due to her waning health, how could she handle both the scripting of the plays and tending to the actors? She herself wasn’t the picture of vitality.

Upon her discharge, Li set out immediately to contact her fellow actors.

Fifth-Sister-in-Law acknowledged the troupe’s predicament: “All of that just to bring some solace to some elderly folks, even if just for a few days. They sang for us daily, not that they were ever paid to do it.”

Fifth Sister-in-Law and other loyal spectators reached out through the grapevine to the city council, trying to secure a new home for the troupe. Some other members of the audience made enquiries themselves and Min Wu trekked just about everywhere to check out venues. Fifth Sister-in-Law knew that Zhang Fan came from Beijing, and looked at her with pleading, innocent eyes full of hope: “Please help us get the word out…thousands of years of history, you see.”

Li wanted to hold to have a meeting with everyone. Both she and Zhou were sick, and the actors weren’t getting any younger either, nor could most of their audience walk anymore. Their lease at Guangya was about to expire—should they keep on going, or disband the troupe?

In October, the troupe resumed their performances, even if only for the last two months left on their lease. The show must go on, and a day with performances was better than none.

Third Sister was now in charge of the scripts, even though she was no longer in such good spirits after her stroke. In the past, she’d been really helpful in buying stuff for the troupe at the market, but nowadays her legs no longer obeyed her, even if she still wanted to help. When she shopped around for venues, she carried a bag of steamed buns and walked around all day long from park to compound, even to the trendy glass houses designed by a Dutch firm on the steep hillsides of Liuzhou... The answer was one and the same: “Don’t even bother. It’s way out of your budget.”

Third Sister never competed for the juicy roles. She was happy to play any character, from guards to maidservants, and stayed to help clean up after the show. She was a widow and had no support from her good-for-nothing son and abusive daughter-in-law. Whenever the troupe had a day off, she spent it at Liuzhou Park, like a wandering soul, sharing her meal of steamed buns with the fish in the pod.

In Hong Kong auteur Wong Kar-Wai’s film Days of Being Wild (《阿飞正传》), Leslie Cheung’s character has a sobering quote: “I’ve heard that there’s a kind of bird without legs that can only fly and fly, and sleep in the wind when it’s tired. The bird only lands once in its life…that’s when it dies.”

Third Sister was like that legless bird. She landed on January 6, 2020.

6/6

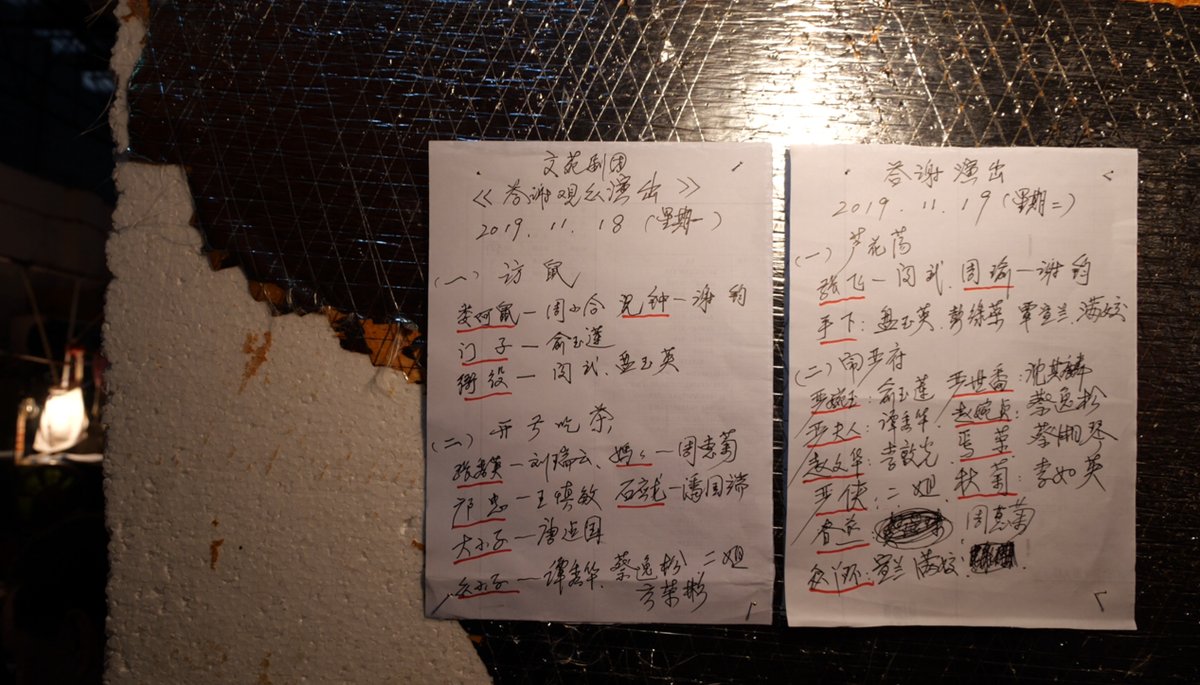

In the end, the troupe failed to find another venue. Their farewell performance was scheduled for November 19, 2019.

Li Lizhu addressed the audience before the show started: “Today the Wenyuan Guicai Opera Troupe bids farewell to our audience. We will regroup in the future, but I find myself quite sad about this particular moment in time.” Here, she choked up a bit. “We’ve been together for more than 30 years, and it is now time to part ways temporarily. We still want to do this together. We will have our encore.”

Li went backstage after her short speech, and actor Cai Yisong encouraged her to regain her strength as soon as possible. Their troupe leader was sick, and so were their main actors; those who were left had no choice but to leave.

A pair of iron tongs did away with the red and yellow cloths that had brightened up the ugly shed. Gone were the costumes that once lingered on the hangers, and the two broken clocks were also dismantled.

Min Wu had his own farewell words to Li before parting ways: “Aunt Li, please take care of yourself until we meet onstage again.”

“Don’t worry,” said Li. “I’ll be waiting for your good news about a new venue.”

And so, the Wenyuan Guicai Opera Troupe temporarily disbanded. But Li couldn’t stay idle. Without the stage, it felt as though a part of her was missing. Her audience yearned too for the return of the troupe. In May 2020, she joined forces with several actors to form the Baili Liujiang Drama Troupe. Her heart condition had improved some, and with great effort, she made it back onstage, though not without taking her medication. Once, before going on stage, she fished a bottle from her bag and shook it, until she realized it was empty. From a second bottle, she took two pills.

The new troupe pooled their resources to rent an 80-square-metre space at 4,000 yuan a month. The audience here was even smaller, sometimes just three or four people. Li, now on ticket duty whenever she was offstage, disclosed that they were now performing every day.

In November 2020, the income of the troupe plummeted, and conflicts ensued. They were supposed to keep performing until the end of 2021 but called it quits by the end of that month.

On the day the troupe disbanded for good, Zhang Fan pleasantly surprised Li Lizhu by flying in from Beijing. “You really do have a heart. A ride or die type, right here.”

“This isn’t the end,” Zhang Fan tried to offer some comfort. “There will be more shows. The day will come.”

“Perhaps that’ll be the case,” Li Lizhu conceded with a laugh. “But I surely won’t be onstage for it.

—

On June 24, 2021, Zhou Ying threw a little tea party on the occasion of her birthday for any former spectators who could still walk. Fifth Sister-in-Law begged Zhou Ying to sing a few lines.

Not long after, she called Zhou with a new plea: “Have you found a new venue already? I really want to see a play.”

Zhou, in fact, could not honor her promise that Fifth Sister-in-Law would get to hear Untying the Red Silk Knot Back-Handed. What’s more, Fifth Sister-in-Law could no longer rely on Ms. Lu, her former mobility buddy, who was now wheelchair-bound at home.

Though the stage was now off the table, the tea meetings became a habit on Wednesday mornings. Zhou Ying, Li Lizhu, and a dozen other people—fellow actors, audience members, friends—met every week unless there was a storm.

Li’s daily routine was now reduced to her games of mahjong. Her heart was still under great stress, and more often than not she’d struggle to get to the mahjong table. Her spirits and overall health were worsening after leaving the stage. Her back was deeply bent, her rheumatism had worsened, and her gnarled hands resembled an old ginger root. She gradually lost her ability to walk, and now had to lean against the sink to wash and chop produce.

Eventually, Li was sent to the hospital due to fluid accumulating in her lungs. She stayed there for three days, lying listless on a hospital bed with tubes all over her body. Then, her organs began to shut off and the family was given the choice to either leave her in the hospital or be discharged to live out her remaining days at home.

Li was still conscious and managed to utter: “Go home…go home…”

Her breathing grew increasingly weaker less than three days after returning home. On January 5, 2022, at 3 in the morning, Li Lizhu shook her head tearfully and departed this world.

News of her passing reached Zhou Ying at home, and she could never shake off the impression that her beloved friend had been reluctant to leave. Zhou recalled the troupe’s stint performing in a humid cave in Liuzhou back in 2013. It was spring when the mountain water dripped down the rocks, and the costumes ended up a rotten, moldy mess. But none of this could dampen Li Lizhu’s spirits, because her body was still strong back then. She wore her rain boots daily, and tread through the water so the show could go on.

(Our gratitude goes to Zhang Fan and Qin Zijing for their help with this feature. Other than a few special additions, all photographs for this article were provided by Zhang Fan.)

Written by Sheng Xia (盛夏)