Despite being a small county-level city 300 kilometers from Shanghai, Yiwu has 10,000 foreign residents from over 100 countries

It’s easy to get lost inside the world’s largest small commodities market, but Mohamed Alsalami knows the place like the back of his hand. The 50-year-old businessman originally from Yemen marches through the halls of the vast, maze-like market, passing power drills, LED lights, and plastic wall ornaments for Christmas, stopping only to negotiate for his client:

“This buyer is not just ordering one box of this stuff, alright? He’s looking to buy 100 to 150 boxes of each, so you better get that price down a bit,” Mohamed says, in pitch-perfect Chinese, to one store owner, pointing at different cosmetics items like nail clippers and files neatly laid out on the floor for his client, also from Yemen, to inspect.

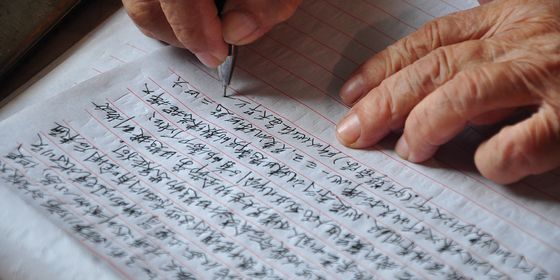

“I’m not ripping you off, that’s the lowest I can do, I’m not making any profit!” the seller retorts, pointing at the prices she has written in black marker on the floor next to the items. But Mohamed is stubborn—after living in the area for over 20 years, he knows how to get a good deal. “Let me take that pen of yours and write the prices for you, then you take a moment to consider, we’ll be out of here in a minute,” he says.

Mohamed is one of over 10,000 permanent foreign residents from more than 100 countries living in Yiwu, a county-level city of around 2 million people in Zhejiang province, around 300 kilometers southwest of Shanghai. This thriving community of foreigners sets Yiwu apart from most other small cities in China. For comparison, Hangzhou, the provincial capital, has six times the total population of Yiwu, but a similar number of non-Chinese calling it home.

Yiwu’s large foreign community exists because the city is a vital international trading hub. Its vast indoor market complex features over 75,000 stores selling Chinese-manufactured Christmas baubles, umbrellas, children’s toys, and pretty much everything else in between for export. China’s “trinket town” attracts buyers and traders from around the world for business trips where they source suppliers and find goods to send to their home countries. But Yiwu has also become a permanent home to a diverse population of foreign residents like Mohamed, who play various roles as global commercial agents, cultural ambassadors, and ordinary people contributing to the unique culture of their adopted home.

Create a free account to keep reading up to 10 free articles each month

Welcome to China’s Most International Small Town is a story from our issue, “Small Town Saga.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.