Against euphemisms like “Big Aunties” and a culture of shame, young Chinese women are speaking up for menstruation

“I would rather die,” my friend sobbed, telling me how her “Big Auntie” made her feel depressed. At age 13, I looked at her pale face and genuinely thought that a dear relative had passed away. But as more and more girls around me started whispering to each other about their “Aunties,” I grew puzzled.

After I sat through the most blush-inducing session of my biology class in middle school, I finally learned the truth: 大姨妈 (dàyímā, Big Auntie) was a euphemism for menstruation. In China, the menstrual period is often referred to as 例假 (lìjià, routine break), 亲戚 (qīnqi, family relative), 那个 (nàge, that thing), or even 倒霉 (dǎoméi, bad luck) by some people of older generations, instead of its proper terminology, 月经 (yuèjīng).

“Auntie” is one of the most common euphemisms. Its origin is now unverifiable, but its popularity is hard to miss, even on the big screen: In the 1999 blockbuster film King of Comedy directed by Stephen Chow, a character played by beloved actress Cecilia Cheung says, “My Auntie came visit me.”

Though dayima might seem as innocuous as “Aunt Flow” in English, the euphemism is just part of various taboos around menstruation in China, which young women have become increasingly critical against.

Gracy Xu, a 26-year-old woman in Beijing who prefers not to use her real name, claims that her period would immediately stop whenever she eats cold food. “I thought it was coincidental. But the same thing just literally happened every time.” According to folk beliefs rooted in traditional Chinese medicine, coldness could block one’s qi (energy flow) and blood flow on one’s period. Therefore, many women believe they should refrain from swimming, taking cold showers, or eating ice cream during these few days of the month. Instead, brown sugar and ginger, classified as “warm” foods in traditional medicine, are believed to help relieve the discomfort during periods.

Some other taboos, however, are more indicative of entrenched stigma around menstruation, not just in China but in many other cultures around the world. For example, a common but now contested folk belief dictates that women’s bodies during periods are too impure to carry out worshiping rituals in Buddhist temples.

The shame toward menstruation extends to menstrual products. Many Chinese women grew up to understand an unspoken signal—if a female classmate or colleague squeezes by you with a frown and a whisper of “you know...” it’s time to give them a pad for an emergency. The next step is to slide the pads discreetly into their sleeve, as fast as a spy sneaks weapons.

On Chinese social media app Xiaohongshu (RED), a popular post shows a sign in a public bathroom that says it offers free sanitary pads, but the term “sanitary pad” was replaced by a funny nickname: “large-size adhesive plaster (大号创口贴).” According to many Xiaohongshu users, when they purchase pads from stores, the cashier often puts them in an opaque black plastic bags separate from the rest of the purchase.

This March, the black plastic bag sparked a trending debate on Weibo. “Why would anyone advertise their period?” wrote some netizens who supported the move, arguing that the bag is a caring service to women who are too shy to make their cycles public.

Many others, however, respond with a tough stance and find the bag to be evidence of “period shaming,” which they deem disrespectful to women’s bodies. “Do you also feel too shy to display your toilet paper?” They argued that menstrual products should not be treated differently from other items catering to biological needs.

With rising awareness, the use of language is also changing. For example, Ningbo Lishe International Airport won a round of applause from female users on Xiaohongshu simply for using the term “menstruation” on a bathroom sign.

Meanwhile, a Suzhou branch of chain supermarket RT-Mart designed a new slogan for its shelf of sanitary products: “Stop Period Shaming.” Although many applaud the message, some call the move “news-jacking” and “hypocritical,” believing RT-Mart is appropriating the trending topic solely for a marketing purpose. “It seems like the price of sanitary pads keeps going up...Why not offer actual help, such as marking down sanitary pads?” critiques one user by the name Gakki on Xiaohongshu.

While urban, social media savvy women are fighting to break period shaming online, some women in the country still struggle to buy period products. In 2020, Weibo user reacted with shock to news of online merchants selling unpackaged sanitary pads at 100 piece for 21.99 yuan, not realizing these dodgy-looking products are the only affordable option for many women in the country. A 2020 article by BBC News points out that each year, a Chinese woman spends from 200 yuan to over 1,000 yuan on menstrual products, which can be a financial burden to the 600 million people in China whose average monthly income lies at 1,000 yuan.

In the article, an anonymous feminist scholar pointed out to BBC that there has not been any thorough studies on “period poverty” in China. Some Xiaohongshu users believe that the lack of spotlight on this issue is a manifestation of gender inequality, in which women’s basic needs are ignored. “If men had periods, I’m sure they would be handing out free pads on the bus,” one commented sarcastically.

As reported by Chinese magazine Sanlian Lifeweek, in 2020, students from Chengdu No.7 High School donated a year’s worth of pads for 800 girls in the mountainous region of Liangshan, Sichuan province. However, in a survey carried out through this project, many Liangshan girls claimed to not have started their periods, only to change their answer when the organizers revealed they could pick sanitary pads based on their survey responses.

Sometimes, the culture of shame around periods even impacts education: Zhang Qing, a Chinese teacher at Liangshan’s Sikai county, told Sanlian that some female students would take days off for “stomachaches,” but she would later find blood on their chairs.

Writing this article reminds me of my mother, a bold woman who disregards the boxes society puts around her. In my childhood memories from the early 1990s, she was always too lazy to carry a purse to the food market, so she instead tucked cash and change into her sanitary pad package. After each intense bargaining session with vendors, she would elegantly pick loose change from her special purse, generously showing them the writing on the package.

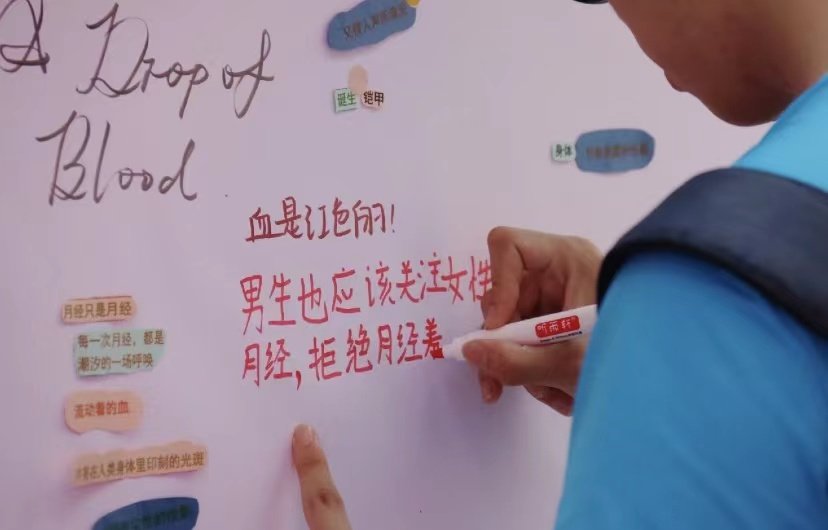

Many new educational campaigns now aim to help more women become more open about their periods. On this year’s International Menstrual Hygiene Day on May 28, the sex education team at Guangdong University of Foreign Studies also curated a period exhibition. One male participant signed in the picture, “Men should also pay attention to period. No period shaming.” On the same day, Echo Planet, a Guangzhou-based sex education start up, held a Menarche Party to celebrate girls who have just had their first period with a concert, cakes, drinks, and activities.

Perhaps, as the girls at the Menarche Party share their period stories in front of a supportive crowd, and make “menstrual bracelets” to mark their cycle, they are slowly lifting a corner of the taboo and shame around menstruation that weighs over our society.