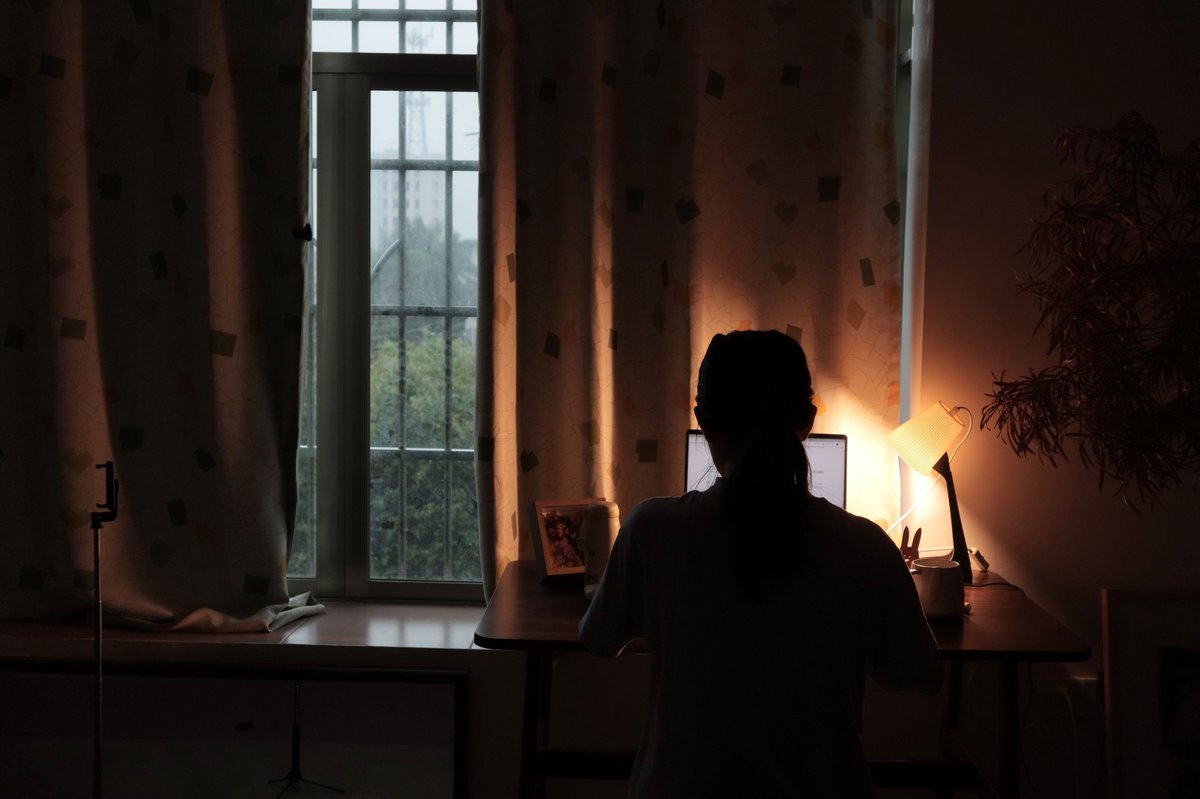

While reconciling with her own trauma, 32-year-old An Chi hopes to bring feminist ideologies to her small hometown

An Chi always wears a hat and mask to cover her face when she goes to visit her grandma in southern China’s Guangdong province. She wishfully thinks this might shield her from the neighbors’ prying eyes, and hide the fact that she’s a 32-year-old unmarried woman without what they consider a proper job.

“As someone who’s relatively unfamiliar to the townspeople, you will become the topic of conversation. They are keen to learn more about you so they can gossip with others,” An tells TWOC under a pseudonym.

Since she left home for college in Guangzhou, the capital of Guangdong, in 2010, An has never pictured herself back in the small town near Zhaoqing again. But in June 2022, after a three-year struggle with depression, An made the surprising decision to quit her job at an internet company and move back to her hometown to work as a full-time content creator on social media platforms. Calling her return a “feminism survival experiment,” An started a channel on Bilibili, a video-streaming platform similar to YouTube, to better document her life and share her thoughts on issues women face in the small town. She also tries her best to attend lectures and other activities hosted by feminist communities outside her hometown and then relay the things she learns back to her friends and family.

Inspired by psychologist Zhang Chun’s concept of “female depression,” a condition experienced by many women who constantly face scrutiny, endure unequal relationships, and encounter dismissive statements from their partners whenever they tried to voice their opinions, An believes it’s necessary to reflect on her upbringing in order to better understand the roots of her insecurity and her ongoing struggle with personal identity.

She wants to find answers to some questions she’s had her whole life, like why women aren’t being respected even though they bear most of the hard work of raising a family, and why some married women with steady jobs and kids still suffer from their relationship and family ties. At the same time, she hopes to bring what she has learned about depression and feminism back to her hometown to help those in need.

Her experiment got off to a rough start. Conversations with her parents often inevitably led to conflicts, especially around the topic of marriage. “People are less pressured to get married in cities. But in our town, you’ll be discriminated against and become the subject of gossip if you’re not married by 30. The way people treat you highly depends on whether you’re following the societal norm,” says An.

In retaliation, An bombarded her parents aggressively with questions like “What does marriage truly mean?” “Are you genuinely happy in your own marriage? If not, why are you trying to force me into a marriage?” The conversation would usually end with her mother in tears.

In An’s hometown, a woman is expected to get married in her 20s. The ideal partner is often a rich man so she can boost her social status. It’s also common for them to have babies before 30, with a strong preference for sons. “Then your in-laws won’t treat you badly. If you are like my mother who is ‘unfortunate’ to have daughters, you may be in trouble with your mother-in-law. At a certain point, your husband will probably abandon you because you can’t accomplish the task of carrying on the family lineage and use that as an excuse to justifiably cheat with someone else,” An shares with TWOC.

According to An, her mother is seen as a failure in the neighborhood for having two daughters. She has a job, but is still responsible for all the housework at home—because, An believes, she feels indebted to her family.

An is especially disappointed that her mom still likes to remind her that “girls can’t achieve big things.” Even though An graduated from a prestigious university, and made financial contributions to the reconstruction of her family home and her grandmother’s hospital bills, her mother would still preach this idea whenever she falls short of traditional social expectations.

The preference for sons is deeply rooted in China’s small towns due to the belief that women will eventually “marry out” and join their husbands’ families. When An’s grandfather passed away, he only asked for his two sons and An’s male cousin on his deathbed. An and her younger sister were excluded from the conversation. “I don’t blame my grandpa because I believed at the time that telling his final wishes to his first grandson was the right thing to do. But I was still a bit upset since my sister and I were considered unreliable just because we are girls,” says An.

Even just walking on the street of her hometown, An feels objectified. When she was on her way to hike a nearby mountain in her khaki shorts this March, a man in his 30s on a motorcycle whistled at her. To avoid uncomfortable interactions and prying eyes, An often dresses plainly. “Even though locals are trying to dress prettier than before, I don’t think women can wear camisoles in my town. Sometimes when I apply makeup and wear a dress, people would just look at me disrespectfully. The fear of being judged puts immense pressure on us,” adds An. “But now I’m trying to just dress comfortably for myself and disregard what others think.”

Despite the challenges and deeply rooted beliefs, An still tries to share feminism-related content with her friends in the town through WeChat, encouraging them to open up about their experiences and insights. She sees it as a sign of success that more and more of her friends are reaching out to her for advice on all kinds of issues: Should they get a divorce, or cave in to family pressure and stay in a loveless marriage? Is it a good idea to start over in a more open-minded city after a divorce? One friend in her 30s shared her anxiety and pressure from her family on having a second child. Some friend of hers even suggested IVF, despite her hesitancy. “The fact that she shared this with me means she must feel pain and anxiety. She’s just not sure what to do next,” says An.

An would encourage her friends to think about questions like “Do you know why this happened?” “Do you know what we’re bearing now?” She also shares videos such as a recent (and controversial) online interview between three elite students from Peking University and Japanese feminist icon Chizuko Ueno on what freedom for women means. However, many of An’s friends found the content too long and heavy, leaving them confused about how the topic is relevant to their lives. “But sometimes a few of them would surprise me by sharing Douyin videos on feminism,” says An.

At home, there is more mixed success. When An attempts to share ideas about the invisible challenges faced by women with her mother and younger sister, who is in her teens, they dismiss her ideas as preaching.

“They assume that since I have gone to college, I know a lot. But they don’t think that’s relevant to them,” says An. Therefore, instead of spreading feminist theories, she decides to just ask her father to do specific things like taking care of her grandmother so her mom doesn’t have to bear all the hard work. At the same time, she makes sure to point out how unfairly her mother is being treated in marriage.

“For the longest time, [my mom] just tolerated everything in silence. [With my encouragement] she now voices her complaints more in hopes of getting more help and validation for all her hard work,” says An.

Recently, An was thrilled when her sister came to her to talk about her boyfriend, who wants An’s sister to dress more conservatively and show less skin. She found it annoying but fell short of coming up with a counter-argument. An took the opportunity to explain to the younger woman from a feminist point of view why she feels this way, and the fact that her boyfriend’s comment is a product of misogyny and the objectification of women. Though she’s not sure how the story ended, An is glad that her sister at least went on to have a conversation with her boyfriend about her feelings.

While promoting feminist ideologies, An is also learning more from the community for her personal growth. Since 2022, An has actively participated in online communities across the country on fostering feminism awareness, education, and communication. This June, An returned to Guangzhou for a workshop in Nüshu, a syllabic script used exclusively by women in Jiangyong, a small county in central China. During a workshop to learn the disappearing script, she wrote down, “Girls should be brave.”

An is also inspired by the initiative from the Women’s Federation in Guangzhou, a government-led organization that advocates for women’s rights and provides female workers with meals, housing, entertainment, child care, and access to feminine products like tampons and sanitary pads. She plans to build a space for local women to have open and honest conversations in her own house in the next few years, as her parents have moved out to live with her grandma. “I hope we can have a place where we get to express ourselves freely and offer a new environment for women to escape from their everyday lives,” says An.

An hopes to connect with more advocates for female empowerment, and bring experts to her hometown to raise awareness, though she isn’t sure how this will be received by the women in her group. “Everyone is busy with their own responsibilities. They need to take care of their families and children,” she worries. “Will they have time to participate in activities that will probably be irrelevant to their immediate needs?”

All worries aside, An is taking things one step at a time, bearing in mind her own mental health. Right now, her main focus is to get along with herself better. In her videos on Bilibili, she talks a lot about how complicated marriage is in small towns and shares her anxiety about being in big cities. She is happy to find that people are resonating with her as her channel has amassed over 800 followers.

“I don’t feel the need to do anything too rebellious [to challenge the status quo]. What I’m trying to do is to treat myself better and reduce the [gender] burden laid on me,” she says.

“Girls Should be Brave”: A Feminist’s Bumpy Journey in a Chinese Small Town is a story from our issue, “Small Town Saga.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.