From exclusive luxury for royalty to the pride of the People’s Republic, ice cream in China has a long and sweet history

Record heatwaves have been sweeping China recently, with Sanbao, Xinjiang, hitting a scorching 52.2 degrees Celsius—the country’s hottest-ever recorded temperature. Beijing, meanwhile, suffered three consecutive days of temperatures above 40 degrees in June for the first time. One small comfort amid this deadly heat is China’s vast range of ice cream options that have refreshed people for generations.

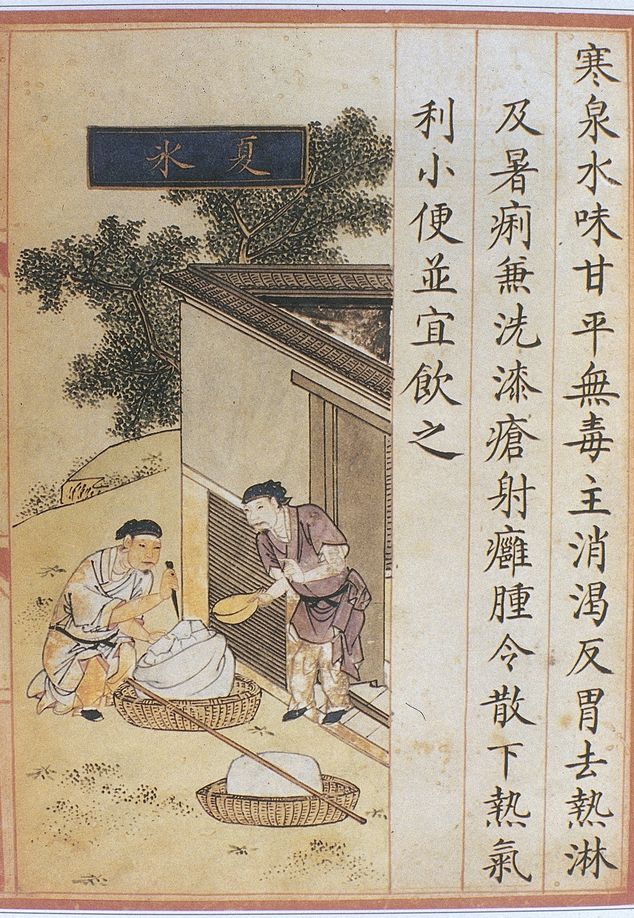

In fact, versions of ice cream have been around for centuries in China, long before gelato emerged in Italy. In the Tang dynasty (618 – 907), for example, one popular dish was sushan (酥山), a frozen dairy product made from the cream skimmed from goat’s milk when making cheese. To make it, people would heat the curd (酥) until it was close to melting, before sieve it so the liquid dripped into molds that resembled mountains (山). Then it was cooled with ice until it froze, decorated with flower petals, and finally served as a delicious creamy treat. In Tang poet Wang Lingran’s (王泠然) “Ode to the Suhe Mountain (《苏合山赋》),” he described it as having a texture between solid and liquid, melting as soon as it touched the tongue.

Sushan was often served for royalty, and murals in the tomb of Prince Zhanghuai, second son of Emperor Gaozong of Tang and Empress Wu Zetian (武则天), in Xianyang, Shaanxi province, show servants offering sushan to the prince.

It was also around this time that ice began to be traded by merchants for consumption by the general populace, not just royalty. That didn’t mean everyone could afford icy treats, though. According to Miscellaneous Notes on Gods and Fairies (《云仙杂记》), a book of anecdotes on officials and other well-known characters during the Tang dynasty, ice and snow in the capital Chang’an (present-day Xi’an) cost as much as gold during the summer months (the ice was collected in the winter and then stored in underground cellars for the rest of the year).

During the Song dynasty (960 – 1279), restaurants for regular folk began to proliferate in cities, and so too did “iced beverage stalls.” The memoir, The Eastern Capital: A Dream of Splendor (《东京梦华录》), written by official Meng Yuanlao (孟元老) in 1127, describes the scene in Kaifeng, the capital of the Northern Song dynasty (960 – 1127), during the summer: “[People] either stay in well-ventilated pavilions or along the water, savoring the coolness of ice-filled containers while enjoying chilled fruits…fresh lotus seeds and fish.”

Urbanites in the capital could get their hands on cool treats, but officials still enjoyed more icy privileges: The Song court provided free ice to officials during the hottest periods of summer to keep them cool. Emperor Xiaozong, on the other hand, apparently suffered from stomach pains due to excessive ice consumption according to the History of Song (《宋史》), a historical text written in the following Yuan dynasty (1206 – 1368).

During the Yuan, imperial chefs developed a new frozen dessert: binglao (冰酪), literally “iced cheese.” The recipe for this frozen treat, flavored with fruits, honey, wine, and other liquors, was kept secret by the imperial palace, though a common story goes that Kublai Khan, the grandson of Genghis Khan and an emperor of the Yuan dynasty, shared the treasured recipe with Italian explorer Marco Polo who then introduced it to Italy. Historians, however, still debate the true story of gelato’s origins, and there’s little evidence of such a transfer of state secrets via Marco Polo.

Later, in the Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911), the imperial family even consumed a concoction made from ice, dessert, and plums as medicine. It supposedly helped cool the body, alleviate pain, and could treat a cough.

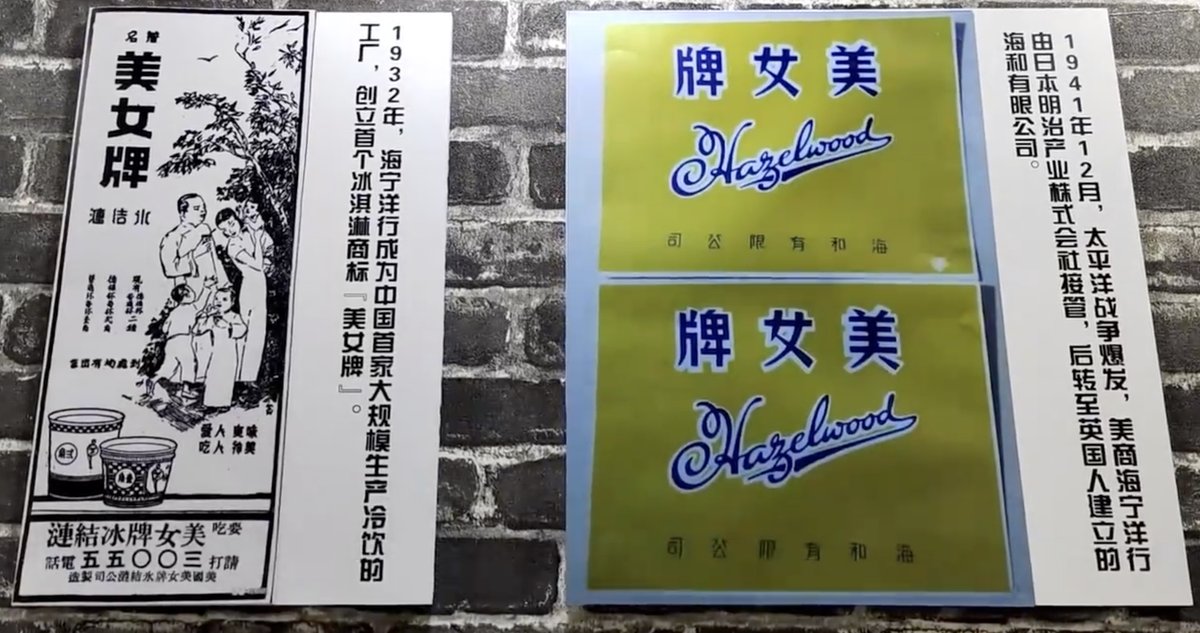

As the country entered the 20th century and the imperial system melted away, ice cream of the sort familiar to us today became more widely available. The names commonly used today, 冰淇淋 (bīngqílín ) or 冰激凌 (bīngjīlíng), also emerged. The first mass-produced ice cream was by Henningsen Produce Company, an American egg business established in 1913 in Shanghai that began selling popsicles in 1925, in part to supplement its business during the low egg-trading season. The company branded its ice cream Hazelwood in English, and 美女 (“Pretty Woman”) in Chinese. By 1935, Henningsen was selling 1,000 packs of ice cream a day to retailers for around 1.67 yuan each (a blue-collar worker’s monthly salary in Shanghai was around 20 yuan at the time). Hazelwood quickly captured around 70 percent of the ice cream market in the country.

After the Communist Party of China came to power in 1949, however, they quickly brought the American company under state control, renaming it Shanghai Yimin No.1 Food Factory. They also changed the brand name to Guangming (光明) or “Bright” in 1951, to represent the bright new future ahead of “New China” after the Communist Revolution. Jiang Zemin, who would become China’s president in the 1990s, was the company’s deputy director for a time.

Bright also rebranded with a torch-shaped logo and a distinctive blue paper wrapper. The company even launched a promotional campaign in the early 1950s, driving around the streets of Shanghai in a modified American car adorned with the words “Bright is Here (光明问世)” and loudspeakers spreading the news of the brand. Female workers at the factory stood in the open-top car holding more promotional signs for the brand, while salespeople followed around on foot carrying boxes of the ice cream to sell.

Over the course of the 20th century, Bright products became iconic and popular treats for urban residents. The ice cream was available in many forms (popsicles, bars, sandwiched between wafers) and flavors (including orange, lemon, milk, red bean, and even sweet rice wine). Its saltwater popsicle, one of its most popular products, cost just 3 fen, though it also produced more luxury ice creams, such as the “purple ice cream” which cost 2 jiao 2 fen.

Bright went from producing around 800 tons of ice cream in the 1950s to 15,000 tons in the ’90s. But China’s market reforms that began in the 1980s have made the ice cream market fiercely competitive—the industry is now worth 160 billion yuan, and around 3,000 new related businesses are entering the market every year, according to market research firm Daxue Consulting. Even traditional liquor brands have entered the market, with Maotai releasing a baijiu-flavored ice cream in 2022, selling over 5,000 servings in just seven hours.

However, prices aren’t what they used to be. Last year, consumers complained online about high-end ice cream brands with sold single popsicles for up to 60 yuan. These premium treats were called “ice cream assassins (雪糕刺客)” for the surprisingly high costs that crept up on consumers when they got to the checkout counter. But even these pricey ninjas are an improvement over the Tang dynasty, when only royalty could afford an icy treat on sweltering summer days.