The Yellow River township of Taosi hosts a 4,000-year-old solar observatory with ancient archaeological treasures underfoot

As Yang Yulong adjusted his camera perched on its tripod, he started to get impatient. “Is it time?”

With everyone still drowsy, it took a few moments before anyone answered. It is 4:40 in the morning, but our group of four had already been up for an hour, having spent 45 minutes traveling on the highway and then on a section of dark, bumpy country road. “No, the sunrise isn’t for another 20 minutes,” someone finally replied. Unperturbed, Yang, a retired amateur photographer in his 60s, returned to the task of angling his tripod back and forth, and tweaking the settings on his camera to be ready for the big moment.

After all, he wasn’t trying to capture just any sunrise: This was a sunrise at what is believed to be China’s earliest solar observatory.

To people not familiar with the area, this ancient site in the small township of Taosi in Linfen, Shanxi province, has a peculiar appearance. Under the dim morning stars, a crescent terrace rises slightly above a vast wheat field. Thirteen thick pillars stand side by side, looming over the early visitors, forming a bow-shaped structure arching southeast. A close inspection reveals that the gaps between the monoliths are only a few centimeters apart, except for one large gap on the northern end. A small round platform sits at the center of the terrace, from which three polished masonry lines on the ground radiate toward three specific apertures. Over the pillars, barely visible in the morning haze, a gentle hill stretches across the horizon.

While my traveling companions were busy getting ready to capture the critical moment, I strolled among the pillars, trying hard but failing to discern the labels on them in the faint glimmer of twilight. Distracted, I stepped into the uneven crop fields to find a funeral wreath in bright colors on a small mound—a tomb. These are a common sight in rural China; when the population grows but farmland becomes scarce, the deceased are forced closer to the living.

One might be forgiven for assuming that Taosi is just like any other village in the area, but this town holds a treasure trove of rich archaeological discoveries. Back in 2003, a team of Shanxi archaeologists dug up the ancient foundation of an earthen wall. While they would normally take the structure at face value (as a very old wall), they noticed something unusual in the trenches—lots of narrow grooves that were clearly human-made, forming a series of gaps between the pillars of rammed earth.

In addition to the discovery of a large terrace in the area, pottery shards and the structure’s southeast orientation led researchers to suspect that this area once had a specific religious and astronomical purpose. Scientists calculated the observation point based on the position of the pillars, finding a round observation base—the base on which I was now standing.

Overjoyed, the archaeologists then spent the next two years carefully reconstructing the monoliths and their hypothetical observations. Using data collected and corrected for astronomical changes over time, they finally confirmed the function of this ancient structure: an ancient calendar used thousands of years ago.

For instance, on the morning of the summer solstice, the sun would shine through the 12th aperture from the south, while through the second aperture, the rising sun of the winter solstice could be observed. And the seventh aperture was used to determine the spring and autumnal equinoxes. However, study of the rest of the apertures remained fruitless, as they were not related to any important dates known to us today. Scientists thus suspected that the ancient residents lived by an archaic calendar lost to history.

While the discovery was groundbreaking, it was not totally unexpected. The southern part of Shanxi has long been known for its prehistoric relics. Nurtured by the Yellow River and many of its tributaries, the area is regarded as the cradle of early Chinese civilization. The small town of Taosi only has a population of a little over 23,000 that largely subsists on growing wheat and corn, but beneath their farmland lay invaluable cultural and historical treasures. Since the 1950s, numerous relics have been excavated, revealing a grand ancient city. Carbon dating puts the metropolis all the way back to the late Neolithic period, 3,900 to 4,500 years ago. Covering an area of up to 2.8 million square meters, the Taosi site is the largest prehistoric city ever discovered in China.

Though this was already his third tour, Yang still brimmed with enthusiasm for Taosi. A Linfen local living in the city’s central district and a proud advocate of local history and culture, Yang was serving as our guide. “At first we didn’t know the location of this site and had to ask the village chief to lead the way,” he told us.

“But when we arrived at his courtyard one morning, he was still sound asleep, immune to shouting or knocking on the door,” Yang recalled with a laugh. “When finally a woman in her pajamas came out of the neighboring house and asked what was going on, we were in such a hurry that we asked the poor woman, who turned out to be the relative of the village chief, to show us the way; we didn’t even give her time to change!”

We had no old lady in her pajamas with us this time, but we did have the rare opportunity to repeat one of the oldest rituals of an ancient civilization. Soon, we were fully awake, infected by Yang’s high spirits as the morning twilight grew. As the earth slowly rotated into place, the sunshine touched the ground and everything came into focus. The first ray of sunshine radiated over the mountaintop and through the pillars. A small ball of fire revealed itself and tinted the sky with a warm hue.

Of course, given the random date we selected for our visit, we didn’t expect to see the sunrise in a particular aperture from the exact spot of the observation point. But a slightly shifted point of view would immediately grant the effect—as long as the sun, the gap, and your eyes (and cameras, in this case) were lined up correctly. After a brief moment, the sun rose above the pillars, and a bright sunny day was upon us.

Our modern worship ceremony for the sunrise, which consisted of what felt like a million shutter clicks, quickly came to a close. In broad daylight, the pillars (reconstructed with gray bricks) seem to lose their magic, but the small observation platform is stunning and genuine. Covered by a thick layer of glass, four concentric circles of rammed earth were clearly the base—made 40 centuries ago.

Any introspection on the enormity of the experience was happily broken by Yang: “Want to get some breakfast? I know just the local food you should have.” Philosophy, in this case, bowed to curiosity and hunger.

Yang knew his food. At a plain-looking restaurant on the streets of Linfen, our arrival caused a bit of a stir. Clearly a spot for the locals, our backpacks, cameras, and strange faces were studied with curiosity, but it was clearly familiar to Yang. Two waitresses greeted him: “You are here!” As Yang gravitated toward the regulars for a chat, I was drawn to a huge basin of steaming chili soup on the front desk—full of tofu and noodles made of potato starch, a typical northern combination. This particular version, according to Yang, is native to the city of Linfen. “You won’t find it anywhere else,” he claimed.

There were also options of jellied bean curd, or doufunao (豆腐脑儿), but the opportunity for some authentic Linfen tofu soup was just too tempting. Then came the salty deep-fried dough sticks, or youtiao (油条), and sweet tangmaye (糖麻叶), another kind of fried dough with brown sugar. From a large rice cooker, a few spiced boiled eggs with tea leaves, were added to our plates and the order was complete.

The tofu pieces were soft but chewy; the tangmaye was crumbly on the outside and moist on the inside with just the right amount of sweetness. Our appetites gloriously sated, it came time to plan the rest of the day, which led us back to Taosi to learn more about the ancient city, rather than the ancient astronomical calendar—sadly without Yang, who went to rest at home.

In the harshness of daylight, we noticed many things we missed during the sunrise; the most imposing of these being large, red slogans on the village walls: “The Ancient Capital of Emperor Yao, and the Origin of China” and “The Roots of Chinese Civilization.” Their apparent propaganda style immediately raised suspicions.

No Chinese history book begins without mentioning Emperor Yao, one of the five great emperors of the ancient Chinese people. However, most accounts are more myth and legend than fact. Emperor Yao was born, for example, when his mother saw a red dragon and became pregnant. The modern study of Yao is filled with conflict, fueled more by bias than science. The competing theories of his birthplace ping-pong from central China to an ethnic minority group from the east. The former is more popular largely because it makes Yao of native, “authentic” Chinese nationality.

Like many records of early human history, there’s simply no way to confirm it. So when we were met by a cheerful young woman from the local Administration of Cultural Heritage, we were eager to ask: “What makes this site the ancient capital of Emperor Yao?” “Well,” she said, “the solar observatory you’ve just visited this morning, for instance.”

Yao was in power some time during the fourth to the third century BCE, and one of his greatest achievements was the creation of the calendar. It was recorded in Sima Qian’s (司马迁) Records of the Grand Historian (《史记》) that Yao sent four of his officials to observe the motion of the sun, the planets, and the constellations. As a result, he was able to determine the four seasons.

Naturally, we were eager to see the relics of this ancient city, and when we asked where they were, we were told we wouldn’t be able to see them because they were reburied for protection when the study was done, except for a few precious relics that were sent to museums. “Some [reburied relics] even have farmers growing crops on top of them, because they are way too deep underground to be affected,” said the young woman.

Though glad that massive pits dug throughout the area didn’t ruin the mystique and put the relics in danger, we were nonetheless disappointed. Still, we glanced over the farmland and exposed earth and let our imaginations run wild.

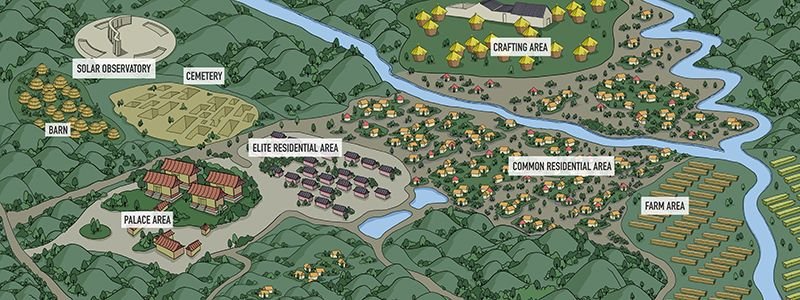

In ancient history, to the north of the observatory, busy crowds bustled by the wells, roads, and pottery kilns, getting on with their daily lives. In the clearly divided palace and elite residences area, the head of the state and his officials would enjoy a luxurious lifestyle, above the common peasant folk.

To the south would have been the cemetery; less than one percent of the tombs excavated here were owned by the rich. Elaborate wooden coffins with up to 200 pieces of buried artifacts of jade, stone, colored pottery, and even human sacrifice, were unearthed—all of them for male occupants. An echo to the modern gap between the rich and the poor, the rest of tombs were much more humble, often simply a pit with a skeleton in it. A small walled area adjacent to the southeast of the main city was the religious area, where astronomical observations and religious ceremonies were performed.

The observatory is a critical link in understanding the city, which left no written history. On this topic, an interesting hypothesis was proposed by scientists Li Geng and Sun Xiaochun in The Chinese Journal for the History of Science and Technology in 2010. The scientists explained that there was a tradition of measuring the length of the noon shadows at the summer and winter solstices, which yielded the shortest and longest shadow length in a year. Only observations taking place in the capital city would be recorded as official.

Based on the numbers from one of the oldest astronomical and mathematical texts in China, Zhou Bi Suan Jing (《周髀算经》, or The Arithmetical Classic of the Gnomon and the Circular Paths of Heaven, first compiled in the Zhou Dynasty (1046 – 256 BCE), Li and Sun calculated the latitude for the location of observations. Their calculations only missed Taosi’s solar observatory by about 0.26 degrees—a remarkably close calculation.

Li and Sun further linked the observatory to a mysterious lacquer stick discovered in a grand tomb in Taosi in 2002, which they concluded was a ruler used to measure noon shadows. The graduations on the stick match the special dates indicated by the solar observatory’s mysterious apertures. Li and Sun thus proposed that the numbers recorded in the ancient texts were passed down from even earlier times. and that Taosi was the origin of them all.

Could Taosi be the capital of an early nation 4,000 years ago? Having seen the solar observatory, I am a believer. But did Emperor Yao rule it? He could have, although his own existence is supported largely by myth and legend. As we toured the village one last time, local residents chatted in front of their bungalows. Like the ordinary people of old, they went about their day, living their life and minding their own business with history beneath their feet.

This is a story from our archives. It was published originally published in 2015 and has been edited and republished in honor of World Bicycle Day and TWOC's upcoming 100th issue celebrations. Check out our subscription plans and discounts that will give you access to more great stories!