Learn the Chinese character for work, labor, and toil

When it comes to Chinese works on maternal love, none can compete with Tang dynasty (618 – 907) literatus Meng Jiao’s (孟郊) poem “Song of the Traveling Son (《游子吟》)”: “Thread in the hands of a loving mother turns to clothes on the traveling son. She adds stitch after stitch before his departure and worries about his return. A grass blade is bathed in spring sun; how can its inch-sized heart return such love?”

Included in Three Hundred Tang Poems (《唐诗三百首》), compiled by the Qing dynasty scholar Sun Zhu (孙洙) in the 1760s, and now a must-read in primary school textbooks, the poem may be China’s most cited work on the topic, even though sewing clothes by hand is now mostly a thing of the past.

Meng wrote the poem while traveling back to his hometown Wukang (in present day Deqing county of Zhejiang province) to fetch his mother, after he took his first official position in Weiyang county (in today’s Jiangsu province) at the age of 50, expressing his gratitude to the woman who raised him and his two younger brothers alone—their father died when Meng was 10.

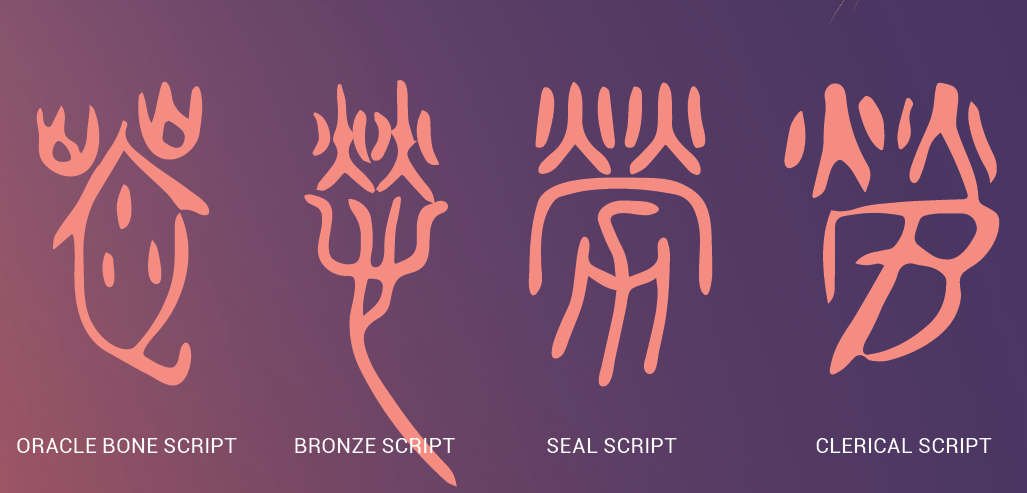

Meng’s scene of a mother, bathed in light, sewing clothes for her son reflects the composition of the earliest form of the Chinese character 劳 (láo, labor, toil), found on oracle bones from over 3,000 years ago—two 火 (huǒ, fire) on top and an 衣 (yī, clothes) below, with three dots that resemble stitches inside the 衣, which was later replaced by the radical 力 (lì, strength) and a form symbolizing a house above. The Analytical Dictionary of Chinese Characters (《说文解字》), written during the Eastern Han dynasty (25 – 220), interprets the form as “[When] a house is on fire, it takes hard work to extinguish it (熒,火燒冂,用力者勞 yíng, huǒ shāo jiōng, yònglìzhě láo).”

While the form of the character has been simplified, its meaning has expanded to indicate toil (辛劳 xīnláo), work or labor (劳动 láodòng), and associated feelings like fatigue (疲劳 píláo).

Since ancient times, Chinese society has despised those who do not work yet sponge off others, or 不劳而获 (bùláo’érhuò, literally “reap without sowing”) as an idiom in Family Analects of Confucius (《孔子家语》) puts it. In more modern times, the idea that “labor is glorious (劳动最光荣 láodòng zuì guāngróng)” took root, with even the Constitution of the PRC extolling: “Labor is a glorious thing for all the citizens in China who have the ability to work.” People who work diligently and make great contributions to an organization or to the country are honored as “model workers (劳动模范 láodòng mófàn or 劳模 láomó).”

Since the 1980s, 劳 has become one of the five key attributes China’s education system seeks to cultivate in students, along with 德 (virtue), 智 (intelligence), 体 (physical fitness), and 美 (appreciation for beauty). Under this framework, primary and middle school students have commonly had at least one hour of “labor class (劳动课 láodòngkè)” each week for labor theory (劳动观念 láodòng guānniàn) and skills (劳动技能 láodòng jìnéng).

However, cognitive labor (脑力劳动 nǎolì láodòng) and manual labor (体力劳动 tǐlì láodòng) are not always considered equal. As the third and fourth-century BCE philosopher Mencius said, “Those who labor with their minds govern, while those who labor with their strength are governed (劳心者治人,劳力者治于人 Láoxīnzhě zhì rén, láolìzhě zhì yú rén).”

Throughout history, many Chinese scholars have expressed empathy with the “toiling masses (劳苦大众 láokǔ dàzhòng),” many of whom struggled to survive as subsistence farmers despite backbreaking labor. In his poem “Watching the Wheat Harvest (《观刈麦》),” Tang dynasty official and poet Bai Juyi (白居易) aired his shame at taking his yearly salary of three hundred dan (石, an ancient Chinese measuring unit that equals 125.5 kilograms) of grain without doing “any farm work,” after witnessing a poor woman with a child in her arms gleaning wheat in the hot May sun. Bai recounts that the woman had turned in all of her farmland’s crop as taxes.

Be it mental exertion or manual labor, overwork can have severe consequences, such as 积劳成疾 (jīláo chéngjí, illness caused by prolonged overwork) or even 过劳死 (guòláosǐ, death from overwork). To avoid such issues, people are encouraged to strike a balance between work and rest (劳逸结合 láoyì jiéhé). Sometimes, though, there’s no avoiding hard work, and all one can do is put in a final supreme effort to get things done once and for all (一劳永逸 yìláo yǒngyì).

On the Character: 劳 is a story from our issue, “After the Factory.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.