Chinese feminist Xie Lihua tells her story of working for women’s magazines and documenting female empowerment in China over 40 years

Stories centering on women, their experiences, and their rights have been a mainstay of the Story FM podcast over the last few years. Online, the word “feminism” in China is inevitably tied to controversy. That’s the reality for modern feminism: It contains many different currents, disagreements, and tensions.

The journey toward gender equality in China since 1949 has been slow and is ongoing. What kind of deeply rooted challenges did the early feminists of the PRC face, and how did they respond? In today’s episode, originally aired on International Women’s Day on March 8, guest host Alexwood (host of the podcast Be a Dodo, or 别任性) chats with Xie Lihua (谢丽华, Xiè Lìhuá), a true veteran whose fight for Chinese women’s issues and rights spanned over four decades. Her story is a first-hand look into how it all began, and how feminism reached the point it’s at today.

1

Tragic Old Times

My name is Xie Lihua and the one thing 2023 has in common with 1951—my year of birth—is that both are the Year of the Rabbit. I’m now 72, and retired, but for some four decades I remained involved with women’s rights and equality in my role as a reporter with the All-China Women’s Federation (ACWF), which created the newspaper China’s Women’s News (《中国妇女报》), and as the founder of a public welfare organization called Rural Women and a magazine called Rural Women Knowing All (《农家女百事通》). In hindsight, I firmly believe that everything’s connected, and that I was fated to tread this path in life.

I was born the middle of three children to a family in Weifang, Shandong province. My older sister was a capable, sensible kid, and my younger brother was the baby boy that the family doted upon. Back then, I never thought that I was at a disadvantage having being born a woman. Up until I was 5 or 6, I’d always assumed that our younger brother was favored simply because he was the baby.

One day, my mother and I went to the market, but our errands were interrupted by the neighbors rushing toward us with news, “Something happened over at your house, your mother has passed.” We both ran home to find that Laolao, my maternal grandmother, had tried to hang herself. When they took her down, they found she’d also ingested pesticide. On that occasion, she was found still alive, and they managed to save her life. But Laolao was so determined to carry out her plans, she just hanged herself again. She was only 62 years old when she died by suicide.

Laolao’s tragedy was rooted in her inability to give birth to a boy. After all, my grandfather came from a “rich peasant” family that expected him to have a male heir. When Laolao proved unable to fulfill these expectations, the patriarch decided to buy a very young woman who I would eventually call my Xiaolaolao, “Little Grandma.”

Xiaolaolao’s life was no less of a tragedy; she had been abandoned at birth and sold to my family at the age of 16 with no education whatsoever. To make things worse, there was no place for her in our family—my grandma and grandpa were childhood sweethearts who loved each other. Xiaolaolao knew well her purpose in the clan, except she, too, ended up birthing two daughters and no son. The family kicked her out to work in the fields three days postpartum—if she’d given birth to a boy, no way would they have treated her like this.

Our dysfunctional household continued like this until after the founding of the People’s Republic. During that time, “class struggle” was the watchword, and any conflict within a family like ours, with one wife from the rich farmer class and the other an impoverished peasant, could be dubbed a type of class oppression. The societal discourse of the time deemed Laolao’s class as the oppressors of Xiaolaolao, and urged Xiaolaolao to denounce us.

Laolao was too kindhearted to bear this situation. She left our town for two months and went to Beijing and Tianjin. Everything was over for her, or so she said; it was time for her to go. We later learned that she came back from Tianjin with everything ready for her suicide, down to the rope that she got from the house of one of her sisters. She really had thought of every possible detail.

Xiaolaolao went on to live a long, ordinary, and apparently happy life; in the end, she even managed to stay on good terms with the family that purchased her. It took many years before I began to see the deep misfortune of her life behind this façade of “happiness.” After all, my own life and consciousness as a woman were undergoing a series of drastic changes along with the times.

2

Passionate Years

In the 1950s, my mother joined my father in Beijing with my younger brother and myself in tow. Thus, I became part of the first generation of “migrant children” in China.

I am part of the “old three classes (老三届)”—the junior and senior high school graduates between 1966 and 1968, the first three years of the Cultural Revolution. My excellent grades in elementary school granted me admission to a first-class institution in town, the Beijing Normal University No. 1 High School, but the Cultural Revolution brought our education to a halt. Educated urban youth could only “go and work in the countryside and mountain areas,” join a factory, or serve in the army. I figured the latter was my best choice.

In 1965, two crucial events took place in my life. Firstly, my older sister joined the Construction Corps in Northeast China. Secondly, like many other young women of my generation, I felt inspired to revolutionize society upon reading the following quote from an article published in the People’s Daily on May 27: “The times are different now; men and women are the same and whatever male comrades can do, female comrades can do, too.” In 1969, I went to Yunnan province to officially join the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and become a propaganda officer.

The slogan “Times are different, men and women are the same” also began to change my life in a more direct way—it tied directly into my first love.

He was five years my senior and already a Party member in our high school days, when he was part of our “Revolutionary Committee” before joining the Air Force. He’d run into some mutual acquaintances of ours in Kunming and asked for my address, and I agreed to meet with him on my first visit home in four years. I really looked up to him, because he’d been originally bound to study abroad in France before the Cultural Revolution changed the course of our lives, and did whatever he asked.

One day, though, I had an awakening. He was hoping I’d become a caretaker for his ailing parents once I returned to Beijing, but by then my enlightenment on gender issues was already beginning and I felt more and more disgusted by this. I’d heard him say stuff like, “Since we’ll have three kids someday, how many boys and girls do you reckon we’ll have?” It may have just been my instinct, but it didn’t sit well at all with me. Eventually, I bid my adieu to him with a long letter where I asked him to send back our pictures together. He readily agreed to our breaking up; he said it was in our best interest.

In hindsight, I see that this moment shaped my future path. I never took part in in the cruelest events of the Cultural Revolution, and again I think that was because I felt this deep, instinctive aversion. Later, when I was deployed to report from the front lines of a battle, I never cheered on any victories. All I could recall was waves of sacrifice and disaster for many families. I can see how later on people often disparaged me as an opportunist who lacked a firm ideological position. But, I just didn’t have it in me.

I spent 14 years in the military and witnessed the blossoming of my literary talents, as well as my many accomplishments in an otherwise male-dominated sphere. I juggled my job with my own writing, publishing a book and a collection of poems. I brandished a pen as my weapon of choice, and became the pride of my fellow female soldiers.

Upon being officially discharged from the army in 1983, I was transferred to work for the All-China Women’s Federation. A new chapter was about to start for me.

3

“Deep Runs the Rancor of a Woman”

A new phase of national recovery followed the Cultural Revolution, and the leadership behind the All-China Women’s Federation was eager to revitalize the organization. Thus, in 1984 the ACWF created China’s Women’s News, China’s first newspaper focusing on women’s issues. We were meant to “promote society to women, and women to society.” As a fresh recruit, I was immediately assigned to the reporting team.

The ACWF had a complaint office that came to deal with plenty of women nationwide raising gender-related issues that had been left unresolved after the Cultural Revolution. I sat and listened to these women from all walks of life sharing with us their tragic fates. Many had struggled to give birth to boys, with the men in their lives biting off their noses and biting their hands in retaliation. However, such injuries were classified as “minor injuries,” and so the attackers couldn’t be punished by the law.

In reality, our fate as Chinese women remained dire long after the revolutionary ardor of the slogans of my youth had faded away. As the proletarian pioneer fighter Wu Qionghua and her fellow soldiers sung in the 1961 film The Red Detachment of Women: “Heavy is the burden of a soldier / Deep runs the rancor of a woman.”

I can recall this one incident I covered as a reporter back then—we’ll call it the “Case of the Henan Model Worker.” A man with the surname Zhu in Henan province was honored as a “model worker” for building a series of roads and a canning factory in his home village. This earned him an emperor-like status among his neighbors. He was 60 years old when he took a fancy to a 30-year-old married woman from the village. Zhu plotted for the woman’s husband to stay away all day with some errands in the cannery and raped her in his absence. The woman was terrified and knew that she’d never be able to denounce the crime, because the locals would have backed Zhu no matter what.

It’s not clear what happened after that, but later Zhu died in his victim’s home, allegedly of a heart attack. With him out of the picture, the cannery closed down and the villagers’ livelihoods were compromised. Thus, everyone ended up venting their resentment on this poor woman.

In the end, Zhu’s widow brought over her family and rallied with the villagers to beat the woman, stabbing the lower part of her body with a broomstick. She was stripped naked and dragged through the local streets. She was nearly dead when the police finally started investigating this shameful event.

The village’s women’s representative welcomed me when I arrived to cover the story, and showed me some pictures of old Zhu’s funeral. It was quite a sight, with over 400 vehicles in his funeral procession—a stark contrast with their treatment of his victim. I waited until the woman was discharged from the hospital to pay her a visit, and she burst into tears when she saw me. She said she did not dare to venture out now, and nobody wanted to work the fields next to her, so she’d been allotted an undesirable plot, the highest in the mountains. Her husband could no longer work in the canning factory, and had hoped to eke out a living as a driver. However, folks constantly punctured the tires of the motorized tricycle he’d bought, wherever he parked it. Their children were also subject to bullying in their school; the other kids often took away their indoor shoes and ripped them apart. Not even the women’s representative had any empathy to spare—she actually told me that the woman was “a whore, trying to take advantage of Mr. Zhu.”

Six of old Zhu’s relatives were sent to jail, with sentences ranging from six months to six years. However, most of them had already been released by the time I got there. In fact, the widow hardly even spent a few days in prison before the villagers welcomed her back with firecrackers.

This whole ordeal shaped my views on women’s issues today. I’d never thought we could be subject to such a terrible experience. Upon returning from the village, I reported this whole story for the ACWF’s newspaper under the title “An Innocent Prisoner.”

The director of that county’s ACWF chapter wanted me to go back to the village for a follow-up mission. But she didn’t have a car, and we spent a whole day trying to find a vehicle without any success. Eventually, the director’s husband had to send a car from his own work unit. The county’s director let out tears of frustration. “Here’s the extent of our low status as women. I can’t even send a reporter on duty with a car; I have to ask for my husband’s help.”

4

The Acute Issues for Women in the Eighties

Story FM: When we look back at the 1980s, we often think of rosy and optimistic buzzwords like “reform and opening up,” “urbanization,” and “economic development.” However, Xie Lihua’s memories of that decade are all about the predicament of Chinese women, including—but not limited to—domestic violence.

Xie Lihua: People often knocked on our door in the middle of the night. Many women showed up badly beaten, with bruised noses and swollen faces. Again, we saw plenty of ears and noses bitten off. This made us finally understand the gravity of the issue of domestic violence.

Story FM: There were also issues related to family planning, the patriarchal preference for boys over girls, land ownership, and women’s participation in politics and suffrage.

Xie Lihua: I remember this really extreme case where a woman hid in a cave to give birth [outside of her birth quota], no doctors involved. Her husband had to use his hands to literally dig out the baby. The mother bled to death.

I heard of local customs in Henan where the family would bury the placenta of a baby boy in the middle of their courtyard. However, if the baby was a girl, they threw the placenta in the toilet or gave it to the dogs.

According to the land policies of the time, women were only entitled to their share of land if they stayed with their husband’s family. If they obtained a divorce, no matter the circumstances involved, they would lose this right, as well as any guarantee of any basic benefits.

When women got married, they were referred to as “married out women (出嫁女),” meaning they’ve left their birth family. But there is no such term for their male partners. Why is that so?

Women’s participation in politics actually reached an all-time low in the reform period. Previously, the female representative of a village would automatically get membership in their village committee, the village-level branch of government. However, this regulation was later abolished, forcing all candidates to run for election to the village committee at the disadvantage of women.

Male candidates would ingratiate themselves with the villagers by inviting them to lavish feasts where they’d gift a crate of Coke to each family, reaping tons of votes afterwards. This was not the case for their female counterparts, and so their support plummeted.

And there’s more. One year, on the occasion of International Women’s Day, China’s Women’s News held a campaign looking for “model women” from a total of “five good families.” However, all I got from looking at the shortlisted candidates was a feeling of significant confinement.

The common denominator to all these stories was the women’s sacrifice for the sake of their families. In one of the stories, the husband became sexually impotent only half a year after the wedding due to a car accident. His side of the family locked up their cars and other household goods that could be sold for a profit to prevent his wife from leaving the marriage. Her mother-in-law went as far as telling her, “This is your lot, your burden to carry. Follow the man you marry, be he a chicken or a dog.” And indeed the woman was trapped in this situation for the next eight years. During this time, she’d asked her husband to teach her how to repair electrical appliances and do some other jobs, so she was praised for her “model family.”

Another of these stories featured a widow who’d given birth after her husband’s death before quitting her job and leaving for the countryside, where she took care of her parents-in-law. Then, there was yet another story where one woman cared single-handedly for her entire family, battling a host of mental issues.

I felt really uncomfortable reading all these manuscripts. I kept putting myself in their shoes and thinking, If I were in that situation, would I be able to do what they did?” No, no I wouldn’t.

This might be hard to imagine nowadays, but back then, our team at China’s Women’s News spent half a year discussing what makes a “model woman.” I also posed a question to the readers—what were the values guiding this selection? Was it just feudal ignorance? Indeed, in almost every county in China you can find memorial arches honoring the legacy of “chaste widows” and “chaste female martyrs” in history, and here we were still upholding the same standards well into the 1980s.

Even my colleagues at the ACWF justified this whole campaign: “We never really considered whether this harked back to feudal, ignorant concepts from the past. We just thought that these were some outstanding women who were willing to sacrifice themselves and endure all sorts of humiliations for the sake of their families.”

To this I replied, “If only you peel your eyes away from that rosy picture, you’ll notice the tears flowing.”

5

Running a Magazine for Rural Women

Story FM: In the ’90s, the Chinese government began to emphasize economic results, and China’s Women’s News also began to encourage employees to set up their own companies and diversify operations. They allotted Xie Lihua a modest 50,000 yuan for her new start-up.

At this time, Xie Lihua was in her 40s, with 14 years of experience in the military plus eight years as a reporter under her belt. She was at her peak in terms of physical strength, experience, and intuition. Now, she was about to embark on a new publication that she would come to recall fondly. Among her peers, she was living the dream.

Xie Lihua: Back then, a friend and I were running a “Singles Club” for young, single women in Beijing. I’d been toying with the idea of starting a magazine with young women as the target demographic, covering issues related to love and marriage. I was aware that I’d need to ensure the magazine was commercially viable through a reliable roster of advertisers and proper management.

However, surprisingly, the head of the ACWF publishing department turned down my idea. He smirked and pointed out that I was running counter to Chinese cultural traditions. “‘Better to destroy a temple than break up a marriage,’ the saying goes. But here you are, with a brand new world order for single women. You better give up on this idea of yours, the sooner the better.”

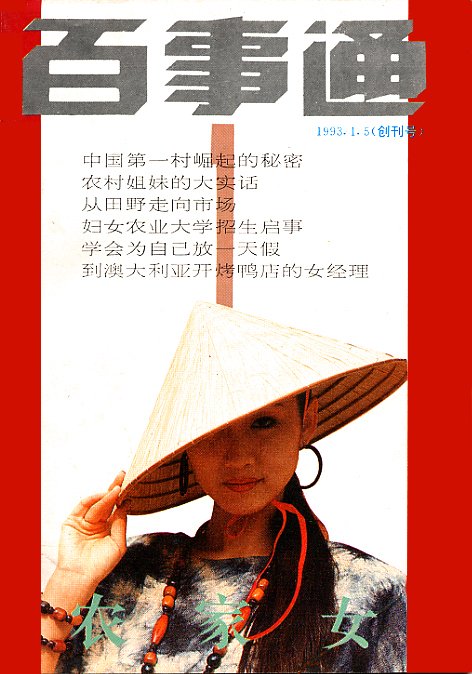

His words felt like a jar of ice-cold water poured all over me, but he had a counter-proposal to raise. He informed me that, in line with the ACWF’s campaign for rural women, a proposed publication titled Rural Women Knowing All (《农家女百事通》) had been approved. Two years later, though, the project remained in development, in search of someone willing to take charge of it.

What was going through my mind as I listened to him, you ask? Well, I thought it didn’t matter what they called the magazine, as long as I got the chance to start my own venture and put my own ideas into practice. Upon my return, I discussed everything with the newspaper headquarters. Eventually, they said they’d give me 50,000 yuan and let me run the project.

Story FM: Xie Lihua returned to her native Shandong, where some of her mother’s relatives still lived, just before the official start of Rural Women Knowing All. In her hometown, she snapped a picture of the front of the old house where she’d been born. She said that many raised their eyebrows at this urban woman from the “elites” coming up with a magazine that rural women were supposed to buy and read.

However, any self-doubts dissipated when she took that photograph and chatted with some of her sisters- and daughters-in-law at her aunt’s house. From that moment onward, Xie Lihua was certain that she fit in by birthright with these women.

Xie Lihua: First things first, I had to figure out whether anyone would actually read this magazine. I just figured that I’d be content with 100,000 copies a year.

The first year had me in a frenzy, turning to every contact I’d amassed at China’s Women’s News to find advertisers and subscribers. It was a miserable first run, with only some 30,000 copies sold. None of the young people from the newspaper wanted to join my project. “Editing a magazine for rural people? You must have too much time on your hands. What kind of rural woman reads books?”

My experiences from the last two decades had taught me that top-down measures were usually effective. Whether it’s starting a revolution or China’s Women’s News, we could count on the support of women from all walks of life. But now, people seemed indifferent to official publications. I realized that the times were changing, and I wanted to address the plight of these women with a brand-new method.

In the second year of the magazine, advertising was my strategy. I decided I would target chapters of the ACWF all across the country. What did these women need? A car for work trips to the countryside and typewriters for office work, none of which they had at the time. I even coined this slogan that urged these local ACWF chapters to “Subscribe to 10,000 copies of Rural Women Knowing All and get yourself a car. Subscribe to 5,000 copies, and get your office Stone brand typewriters.” It caused a commotion in the ACWF. Indeed, I was very bold to come up with such a slogan right after starting out. I didn‘t have any cars, or fancy typewriters, or anything.

I went on my own to the Jeep headquarters in Beijing, without any acquaintances there, asking whether we could get some kind of collaboration that allowed me to offer such discounts to subscribers. The vehicles that often went for 52,000 yuan, I got for 48,000 yuan after some negotiation. So, do the math. A one-year subscription to the magazine was priced at 9.80 yuan—10,000 copies equaled 98,000 yuan, and I was gifting these subscribers a car. I ended up selling four vehicles.

What did they do with those 10,000 copies of Rural Women Knowing All, you ask? They piled them at the local chapters of the ACWF and distributed the copies to those rural women who participated in their activities. Almost no readers bought it on their own initiative.

6

A Rural Woman’s Choice

Story FM: Originally, Xie merely intended to run a publication for her fellow rural sisters. This new venture was a continuation from her days at China’s Women’s News, from the design front to the planning of the actual columns that focused on marriage and family, learning technology, and more.

During the second year of operations, Professor Wu Qing, the magazine’s consultant, introduced Xie to Bai Mei, a project officer at the Ford Foundation who had been conducting extensive research on reproductive health issues in Southwest and Northwest China. Bai Mei placed three consecutive orders of 10,000 copies of the magazine over the course of the next three years. She hoped that Xie would feature a regular column on reproductive health. To this end, she explained to her a series of then innovative concepts, such as the notion that “women’s bodies are our own, and we owe none of them to doctors and men.”

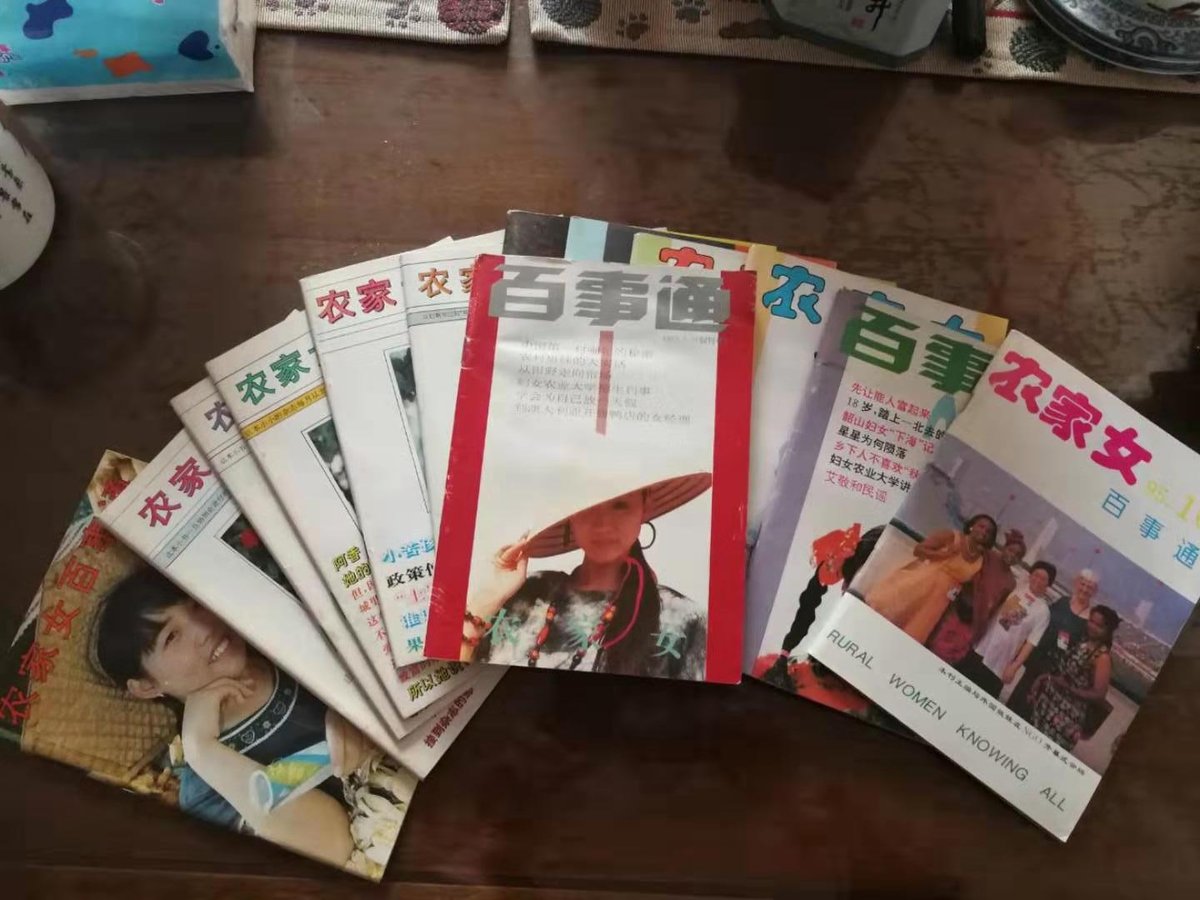

Xie was happy to implement this new trend in her magazine and share what she’d learned with her readership. As a result, Rural Women Knowing All finally ditched the previous framework set by the ACWF’s campaigns in favor of meeting the needs that rural women had long been forced to suppress. This was a huge boost in terms of sales for Rural Women Knowing All. In the third year, the annual sales volume reached 80,000 copies. They scored a new, astonishing record of 220,000 copies in both 1997 and 1998, with a stable readership in the millions.

Besides, the magazine went beyond the scope of its pages. Xie was the editor-in-chief for the next two decades, and during this period she and her team used their influence and platform to carry out several specific and effective actions. In this way, they honored the slogan of the magazine—they drew on real life to influence the lives of their readership.

Xie Lihua: Rural Women Knowing All was most famous for its various letter-style columns, set up as a series of mailboxes managed by either the editor-in-chief or characters such as Sister Chunzi. These columns used simple, authentic language to address questions from their rural readership nationwide.

I told my editors and reporters that they were not there to show off their literary prowess. We were writing with a very clear image of our reader in mind—a woman with junior high or high school education, at most. We wrote for them to understand us, letting truth guide our advice to them.

Story FM: These women wrote letters detailing their concerns for their land, their longing for a career, their fears that a broken hymen would make them ineligible for marriage... Xie Lihua encouraged them sincerely, urging them to never give up reading and writing.

They grouped these newsletter-style columns under the title of “Bookish Girl.” With over 200 issues under their belt, the magazine surpassed the People’s Daily newspaper in terms of popularity in the countryside.

In their trips to supply copies of the magazine to rural regions, the team behind Rural Women Knowing All often discovered the real plight of Chinese women. For example, many of them did not have a name of their own.

Xie Lihua: We found out that there’s a rural custom where you don’t know a woman’s name, but rather whose family they belong to—So-and-So’s Mother or So-and-So’s Daughter-in-Law. So, we made a point of encouraging these women to use their own names.

Suicide was also a common issue.

Indeed, every time I went to the countryside, I would invariably hear the story of some girl who threw herself in the river, or someone’s daughter-in-law who’d taken pills. We saw statistics pointing to a yearly average of over 200,000 rural women dying by suicide in China—25 percent more than the global average.

There were more and more rural women leaving to find work in Chinese cities, however they struggled keeping up with survival skills. Also, they were the first ones to be made redundant whenever their companies went through trouble. But, it’s hard to step into a new field if you’ve long been relying on a single skill—say, weaving—for your livelihood. We really had to find alternatives for them.

Story FM: Over the course of 20 years, Xie and her team actively sought help from professional organizations. They also applied for several public welfare projects striving to alleviate poverty and advocate for greater literacy, education, and suicide prevention for rural women in China.

With this, the magazine introduced a new column dealing with stories of suicide in the countryside, “Why Do these Women Take the Road to Suicide?” They collected stories that were then paired with advice from experts.

In 1996, Xie founded in Beijing the “Home of Migrant Women (打工妹之家)” to provide exchange opportunities, accommodation, and vocational training for migrant women. In 2002, she recruited a team of volunteer lawyers to set up the “Migrant Women Rights Defense Group” and the “Migrant Women Emergency Fund” for an additional source of support for these women.

So far, thousands of rural women have benefited from this public welfare project, with countless others rediscovering themselves through Rural Women Knowing All. They gain plenty from the magazine—practical help on equal terms and, most importantly, self-esteem.

Xie Lihua: Rural women are this mine of resources that we’ve yet to tap into. Give them a chance and a stage, and they’ll burst out with unimaginable power.

Today, our society has more mobility than ever. This gives hardworking people who have ideals and vision a chance to present themselves. Many of these female entrepreneurs you see in big cities are products of this migration. They’ve taken advantage of this stage.

Above all, it’s crucial for people to have a right to choose.

7

We Are in a Worldwide Female Movement

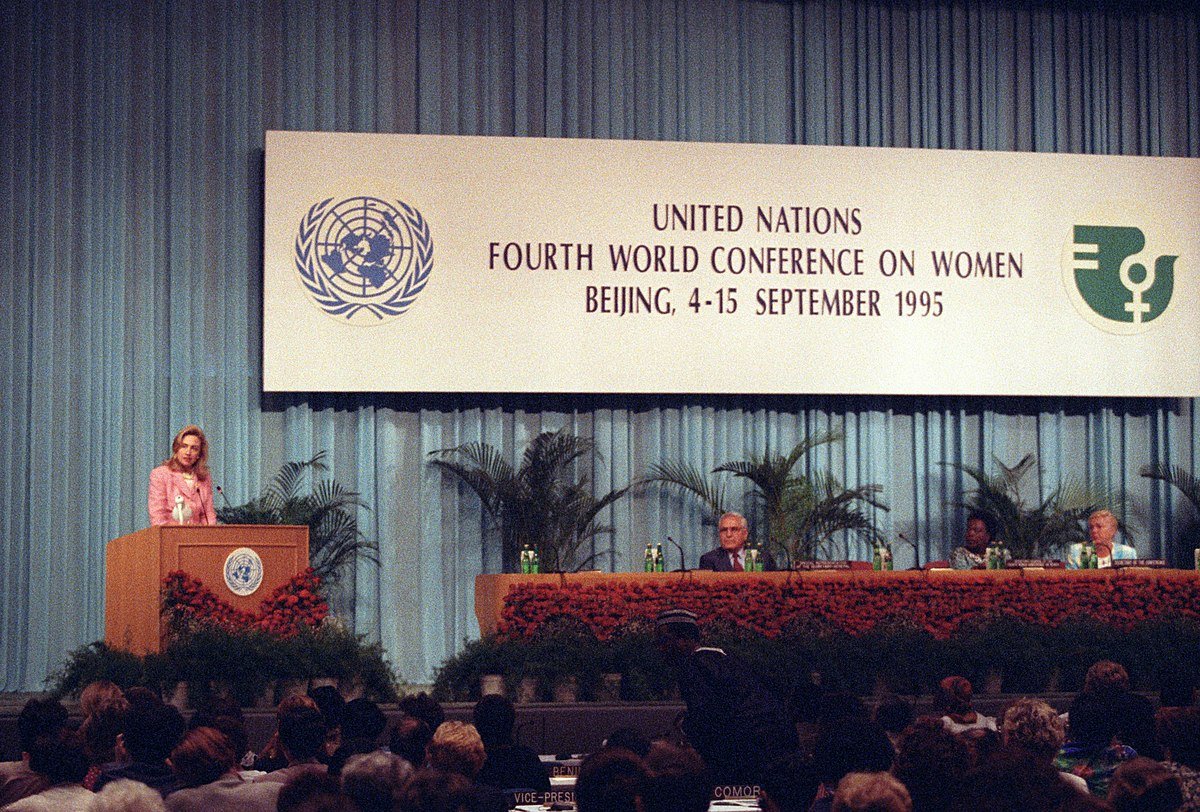

The UN World Conference on Women was held in Beijing in 1995 and represented a crucial milestone in the progress of women’s rights in China. At the time, I was still immersed in the practical issues of rural women and never imagined that I’d ever become connected in any way with the worldwide female movement.

I attended this media conference prior to the main event, with an exhibition hall featuring women’s publications from all over the world. China was represented by publications with a foreign vibe, such as World Woman (《世界妇女博览》), Modern Women (《现代妇女》) and so on. Next to those publications was my rustic little magazine, Rural Women Knowing All.

Women from foreign NGOs saw those other magazines and asked, “Is your publication for the rich or the poor? Why did you choose to feature foreign women on the cover?” However, our magazine’s cover was in black and white and depicted our own working women. We made a sensation in that exhibition hall. It was only then that it dawned on me that my work was already part of the mainstream worldwide female movement.

I wrote an article after I came back from the conference. I knew that for Chinese women to connect with women of the world, it will take more than just putting on a bikini. Rather, it’s about nurturing a real connection and integrating with working women worldwide. And, you must hold yourself in high regard. Nobody will respect you if you don’t. We are meant to be waves in this worldwide women’s movement.

So, I took the lead, and ever since, I’ve introduced myself as the face of Rural Women Knowing All. As a result, everyone learned to equate the magazine with the face of its founder and editor-in-chief.

Story FM: Though some of the issues impacting Chinese women remained relevant in the 1980s and 1990s, after the World Conference on Women, there was a series of dialogues taking place between the Chinese government and people. Ever since, NGOs have been actively exerting their influence in Chinese society. Though they’re facing the same old problems, they’ve got a greater choice of paths to take. Xie was one of the many activists of this golden period.

In tune with the times, there was an emergence of numerous NGOs, TV newspapers, and training courses focusing on women’s issues and rights. Many of us who grew up in this period were also exposed for the first time to feminist enlightenment.

8

To Fight, or Fight Another Day

Xie Lihua: The women’s movement is at a low point right now. I think it’s due to the sensitive nature of certain topics.

Of course, our Labor Law and Women’s Rights and Interests Protection Law have been gradually polished over the years. Perhaps activists nowadays need not resemble their predecessors. In the old days, if I really wanted to help a woman, I’d let her crash at my place, or I’d help her attend a rural school for a couple months. Maybe actions like those are not necessary anymore.

We once met this woman who lost her ability to work as a result of a botched birth control operation during the time of the family planning policy. However, she was unable to gain any compensation from the government for it. I sent someone to investigate, and right away the government folks were onto us, wanting to know how the details about this woman’s case had leaked out. That’s how it is nowadays.

At the time, the woman in charge of rights and interests at the ACWF told me, “Ms. Xie, China is so big. There are just so many women. You’ve gone through so much trouble for the sake of others. Perhaps you should help yourself and turn a blind eye.”

But I cannot possibly do that. I told her, “You are right. But I wouldn’t be who I am if I followed your counsel. The only situation where I wouldn’t help a woman is if she hadn’t found me yet, and all these women have found me.”

In my head, women’s liberation and women’s movements are not the matters of thousands or tens of thousands of people. Instead, they’re woven by the stories of individual women—living women I see in front of me.

I think we shouldn’t be afraid, though. If I were to go back in time to the point where I was running China’s Women’s News and publishing such penetrating articles…I probably wouldn’t be able to do that anymore, but I know very well the roots of those tragedies.

I used to be more aggressive in my youth. There are many things in life that will have you running into a wall. However, there’s only so many times you’ll hit it until you find out how to keep on going. The right path to follow will remain unchanged, even if you have to tread it a little slower.

Perhaps this change of heart has something to do with my age; maybe it’s also related to my dropping some of my former burdens. But, no matter what direction you take, you shouldn’t let decades of your life go to waste. Find something you like, and put it into practice. I feel that everything in my life prepared me to run Rural Women Knowing All; I am always under the impression that my grandma is watching me, as is my mother, and even some rural sisters. The difference is that my heart is at ease now.

Alex: After retiring, Xie used all the proceeds from her investments to continue promoting charities for rural women. In recent years, they’ve held editions of the “Golden Seed Awards,” granting monetary awards to self-reliant rural female entrepreneurs.

Xie is already in her 70s. You may find her enjoying a peaceful life in the suburbs of Beijing. She loves watching TV series such as Hurricane, and is a fan of actor Zhao Liying. She feels that she’s seen enough in her life, that her time and mission are now complete. Today’s female activists may not find her message quite as vehement as they imagine. I think that’s the ultimate message of someone as experienced as Xie is. There’s never a choice that will grant you some best-of-both-worlds scenario. You either choose to fight, or to fight another day.

Images from Xie Lihua

___

This story is published as part of TWOC’s collaboration with Story FM, a renowned storytelling podcast in China. It has been translated from Chinese by TWOC and edited for clarity. The original can be listened to on Story FM’s channel on Himalaya and Apple Podcasts (in Chinese only).