Searching for the origins of China’s festival to the dead on the mountain where it all began more than 2,500 years ago

The clash of cymbals and reverberation of drum beats are punctuated by the ominous echoes of gongs. Red-and-gold-clad performers wave flags and dance in unison, while an army of flutists walk in their wake. The festive spirit is palpable as crowds gather on Mount Mianshan in Shanxi province to commemorate the dead and celebrate the revered Jie Zitui (介子推), a hermit official whose death more than 2,500 years ago supposedly gave rise to some traditions of the Qingming Festival. But there is a catch: these videos and photos are from 2019.

Four years on, as post-pandemic China emerges from hibernation, I set off in search of this pageantry on the sacred slopes where Qingming is said to have started.

My trip begins in Taiyuan, where I board a high-speed train and zoom across the open fields of central Shanxi province to Jiexiu city. The scenery is familiar to much of China’s rail network: an eclectic assortment of buildings in various stages of construction; open fields of trees slowly coming back to life after months of stubborn frigidity; vacant lots of large mounds of timber; crumbling brick walls surrounding workers’ dormitories.

Ensconced between abandoned projects and forgotten ideas, relatives have carved out a space for their loved ones who have passed away—through the window I catch occasional glimpses of burial mounds, freshly tended to and overflowing with flowers whose colors are too bright to ever occur naturally.

Today is Qingming Festival, the day when Chinese sweep the tombs of their ancestors and pay respects to the dead. Makeshift stalls form busy marketplaces alongside the roads to Mianshan. The mountain is 30 minutes from the train station by car and I spot many vendors along the way, most selling the same three things: incense, joss paper, and fake flowers in Cheeto orange, neon green, and fluorescent pink.

I ask my taxi driver if plastic flowers are preferred and he nods. “Fake flowers for the dead, real ones for the living,” he grunts. “Besides, they last longer.” I ask him whether there will be dancing or performers at Mianshan this year. He scowls and says that he does not care for dancing.

A heavy blanket of morning smog obscures the outline of the mountains as we make our way toward the ticket office. From the window of the taxi, I spot shards of sunlight that poke through the pollution; they illuminate a family standing in solidarity in a meadow by the side of the road in an almost celestial fashion. Surrounding a burial plot, their bodies are heaving and shuddering and it seems as if they’re crying. I feel like an intruder, despite the distance between us.

Visiting Sacred Peaks

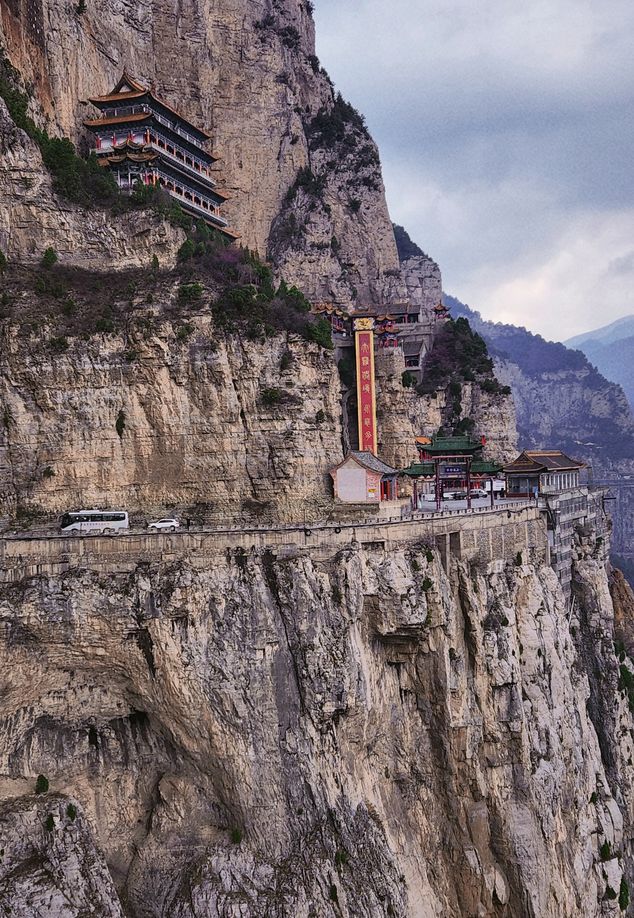

People have been visiting Mianshan for thousands of years—some of the oldest temples that remain standing here today were constructed over 1,500 years ago, but many temples and shrines that succumbed to time were built prior. Historical records state that the first building to be erected on the mountain was during the Northern Wei dynasty (386 – 534), though other records suggest Yunfeng Temple (also known as Baofu Temple, after the cave in which it’s situated) has been a holy site since the Three Kingdoms period (220 – 280).

Mianshan has long since been a mountain of religious and spiritual significance, particularly with its Daoist roots. It’s easy to see how the many caves and grottoes within this range could inspire such deep contemplation, but the site has also featured prominently throughout many military battles over time.

During the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644), Mianshan hosted troops who fought against the invading Mongolian army. The Ming forces there successfully drove the aggressors away from his base on this very mountain to retain Chinese independence.

More recently, these majestic ridges and valleys played a pivotal role during the Japanese occupation; the rugged features and terrain gave the local resistance fighters an upper hand during the guerrilla warfare, allowing them to inflict substantial losses on the Japanese army.

The myriad structures built over the years also incurred damage during the Cultural Revolution, but thankfully, some of the cultural sites survived. While Xuanzhong Temple was partially destroyed, it was later rebuilt and restored to its former glory.

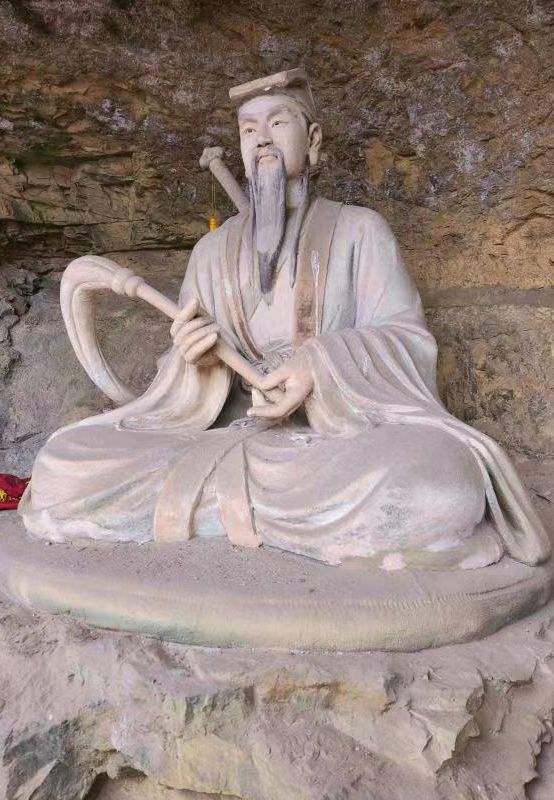

At the foot of the mountain today, a giant bronzed statue of Jie Zitui, its colors fading, greets visitors. Statues and portraits of Jie are scattered throughout the mountain range, as well as a tomb that encases his remains. In a nation renowned for more than its fair share of recluses, Lord Jie is regarded as somewhat of a hermit hero for his unshakable integrity. Jie, an official and scholar, supposedly turned down a job offer from Duke Chonger of the Zhou dynasty (1046 – 256 BCE) and came to live with his mother on these lofty peaks in the seventh century BCE. The duke retaliated by setting the mountain alight. The charred corpses of Jie and his mother were recovered the next day, and the duke felt tremendous guilt, ordering their earthly remains buried in a tomb on the mountain.

Duke Chonger returned to pay his respects in the following years, and decreed that no fires should be lit at around that time each year, giving rise to China’s little-known Cold Food Festival. Eventually, some began to revere Jie as a deity and these traditions morphed into the Qingming Festival.

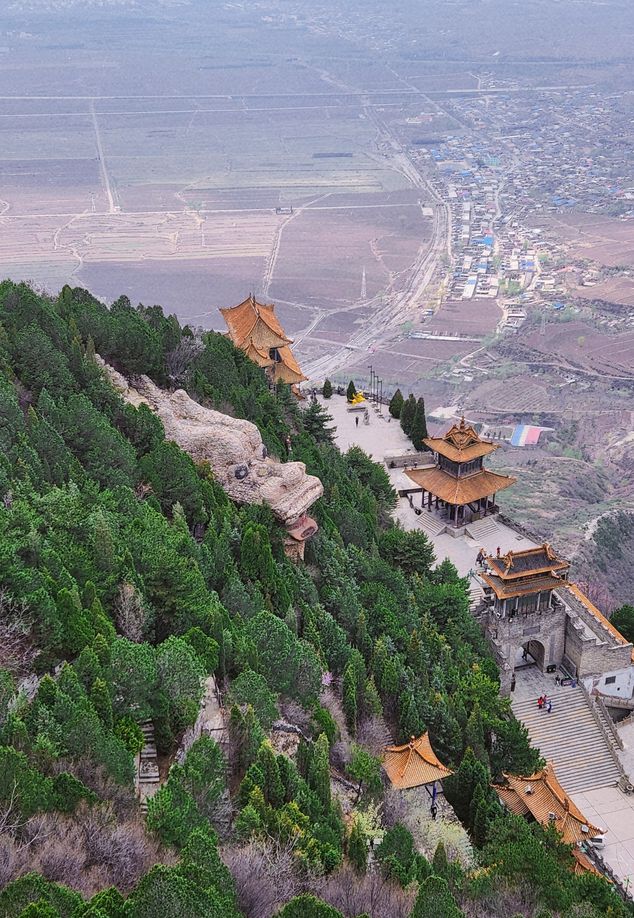

Soon after walking past the statue of Jie and buying an admission ticket (160 yuan including the mandatory bus pass), I’m herded onto a bus and we hurtle up the mountain. Spring is yet to fully reclaim the trees back from winter, so most branches are bare and there is a gloomy atmosphere that lingers over much of the mountain. Two more giant statues of Jie Zitui and his mother look out across the plains from their precarious perch, while domed pagodas and orange-tiled temple roofs are visible even during the early stages of the ascent.

While not immediately evident on the ascent, it soon becomes clear why it’s called Dragon Head Temple.

The first stop is Longtou (literally “dragon head”) Temple and as the name suggests, this temple formation and structure resembles a reclining dragon. The temple was once called Pagoda Cliff, but Emperor Li Shimin of the Tang dynasty (618 – 907) renamed it after he paid a pilgrimage to Mianshan and apparently encountered two supreme dragons here. Soon after, buildings of the complex were constructed so that they coiled themselves around the cliffside in a serpentine grip and the dragon’s head was erected among the trees behind the main building. A popular picnic spot, families sit together inside the beast’s mouth to peel tangerines and shell sunflower seeds, while hikers use it as a pit stop before trekking to the top of the aptly named Dragon Ridge Peak.

The exterior walls of the worshiping house are thick with rows of red prayer tags on which people write down their wishes and dreams. Clamoring for space and shuffling with each gust of mountainous breeze; their movements make a melodious sound, soft and delicate like notes from a woodwind instrument. At any other time of the year, such markers would plead for monetary gains and career advancements but today most write well wishes to the departed.

“I woke up early today, before 7 a.m. I had to tidy the graves of my ancestors before doing anything else,” says Yang Zhilong, a lawyer from nearby Pingyao city. He spots me perusing the scarlet sea of messages to the dead and makes conversation. He is visiting Mianshan with his friends and tells me hiking on Qingming Festival is a common tradition; many I encounter on the mountain have come after sweeping the tombs of their ancestors in the morning. The ”spring outing” is an important aspect of the festival and often comes in the form of hiking, flying kites, or walking through a park.

The Mountain of Hermits

Following the steep trail up the dragon’s back on foot, the cable cars traverse the slopes overhead like little rusty apples, gliding silently over numerous caves that have been home to reclusive monks, philosophers, and poets over the last 2,000 years. I’ve always found the hermit lifestyle appealing, but after reading the fifth placard that details a monk’s abstinence from grain, life among people doesn’t seem so bad.

Many of these hermits followed in the footsteps of their revered masters and stayed here until their deaths. Hua Tuo, a renowned physician who lived here in the second century, cultivated a method of strength building called “frolic of the five animals” in which he emulated the postures of tigers, deer, bears, apes, and birds—at least according to a plaque I come across along the road. Jie Xiang, another hermit resident from the fourth century, apparently cultivated and practiced a mysterious “body-disappearing method.” Both monks made homes for themselves long before any temples or shrines were constructed on the mountain, so they had to make do with a troglodytic life.

Further along the trail is the Stele Forest, a sea of inscriptions on stone tablets. Some are inscribed to or inspired by Jie Zitui; others espouse Buddhist or Daoist doctrines; a few extol the virtue of filial piety. I move on to Daluo Palace, perhaps the most impressive structure on the mountain, a collection of cliffside temples and palaces that supposedly date back to Jie’s time and had been expanded by emperors of subsequent dynasties. I climb up to the Daoist temple carved into the face of the cliff, and find the scene below scattered with temples and shrines to a seemingly infinite number of gods and deities.

The view of valleys and ridges is most impressive from the balcony of the preaching hall, which is guarded by an army of bronzed flightless birds. While at the ground level, the trees stripped of leaves give off a gray and gloomy atmosphere; subtle shades of green and even purple become apparent when you scale greater heights. A stiff breeze roars down the mountain and washes over me; I savor it after a long day of climbing stairs. “I just love this mountain air, especially after it rains,” says Lü Dingyi, a student from Jinzhong city, Shanxi, who comes over to talk to me as I take in the view. “I can taste it; it has a natural flavor and it makes me feel euphoric.”

For Dingyi, who never met her grandfather before he passed away, Qingming provides a connection to the past and a glimpse at additional chapters of her family’s history book. Although her grandfather is not buried at Mianshan, the early morning scenes of sweeping his grave alongside her family members dwell with her throughout the day. “We’ll cry in front of the grave to let him know that someone still cares.”

Rather than ask her about videos and photos of the pageantry from 2019, I keep such questions to myself. Maybe the celebrations will be back next year, I think. Or perhaps Qingming and the tragic memory of Jie Zitui are better served in quiet reflection than in pomp and celebration anyway.

Photography by RJ Fry